This group of paintings has a non-linear connection to events in Syria. I started using this particular form – oil on large wood panels – when Syria was still a relatively tranquil country. None of the iconography I arrived at through shifting oil and pigment presaged, referenced or interpreted any of the digital images that have found their way to comfortably horrified audiences in the West. Yet after five years of following the Syrian nightmare from afar, I cannot help but see Syrian tropes in all of these paintings. This is largely against my will because I wanted to make something static at worst, reaching backwards at best. But nonetheless I have thematically tied these paintings to a place I have never been, post-factum. These are not depictions of events. Nor are they references to anything canned in the public imaginary stemming from the news cycle. I have, however, found in these paintings a roundabout confluence, an appropriation of a past state of mind that now smacks of something glaring in my everyday. I do not know what the relationship is between past renderings and a dystopian present. I just assume there is one because there might as well be.

Qa, 36''x 53'' x 12'', oil on wood.

Digital images from the Syrian nightmare are ubiquitous. The war is practically available by free live-stream, pre-curated based on your brand loyalty. Cartographic enthusiasts and amateur military strategists can find beautiful and precise color-coded maps showing military gains and losses as fronts shift week-to-week. All armed actors put out promos, semi-official testimonies and menacing shout-outs to their adversaries. Imagery from the war, especially when it is abject, is something one either chooses to see or not to see, either in miniature or in as broad a context as possible.

Mrach0, 36'' x 36'', oil on wood.

This year US Press Secretaries have discursively tried to unsee the beheading of a twelve year-old Palestinian refugee by a group known to have received US support, claiming that state officialdom are working to verify the authenticity of the video, which would “give them pause” as to continuing their support of sectarian bloodletting. The same hacks revel in the stage-managed atrocity porn that serves the political expediency of the hour - the agreed-upon narrative of empire, recalibrated with markets and polls.

Kobanegrad, 36'' x 76'', oil on wood.

Despite the insidious bromides that our government peddles, anyone who has bothered to scratch the surface of the Syrian conflict should smell imperialist coercion. The post-modern colonial intrigue of a decadent hegemony has run off its rails; the cheap modernism of a repressive Ba’athist police state, erstwhile ally of empire, is in full wane; Syria has again been returned to a pre-modern slaughterhouse.

Kamo my dear, 36'' x 76'', oil on wood.

No DC wonk, daydreaming of regime-change, can stem this continuous tide of imagery belched out seemingly involuntarily from the Syrian theatre of war. Pundits can only try to ride the current and instruct the public where and when to focus its gaze. This whole dataset will eventually demand a reckoning that cannot merely be legalistic or socio-historical.

Bakur-Sever, 36'' x 76'', oil on wood.

This is where revolutionary art can insert itself: scraping up trampled histories, demanding justice on behalf of vast swathes of humanity consigned to the status imperial detritus. The Syrian war appears to be the pre-eminent global catastrophe for the millennial generation. Yet a timid left struggles in its analysis of the conflict and in articulation of solidarity in resistance to the brutality that our country sponsors and struggles to grasp the pervasive, blinding brutality etched in the Middle Eastern political landscape. Ba’athism is but one retrograde logical stage of imperial coercion, perhaps now transcended by the barbarity of naked cynicism and gamesmanship.

Bel Ching, 36'' x 76'', oil on wood.

Western imperialism has evolved considerably since its gilded age. In the Middle East it has remained grotesque and chaotic. These paintings are about an unbroken chain of empire and dominance. They are plainly in awe of resistance. They explore an inner shock. They also bespeak a cryptic resolve. My great-great-grandfather is buried somewhere in Raqqa. The only society he ever knew was destroyed instantly and without warning. My great-grandmother was a refugee in Aleppo. Her children survived somehow in the city’s overcrowded orphanages, then got shipped around world. The imperialism of my antecedents’ time wended their lives through sufferings I cannot fathom. What I know that I cannot begin to know remains an indexical part of my formation, however confused and bizarre. So I must know that Aleppo is a city of martyrs many times over. And I must also know that at root, despite how awful it is to consider, it is the same forces torturing Aleppo then as now.

Idle, Mezmer, Immorta, Pagent, 36'' x 76'', oil on wood.

Kobane was once upon a time a dusty Berlin-Baghdad Railway “Company” outpost, a tiny token consequence of grand-historical imperialist rivalry. The city now famous as Syria’s Stalingrad, was first founded by Armenians refugees fleeing genocide. History folds on itself. The only way I can imagine engaging such a chain of depredation and vengeance is through unreal images.

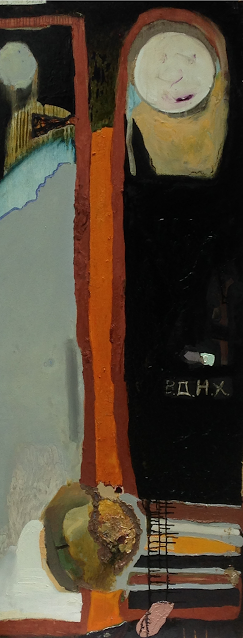

a : man : named : tikhon, 36'' x 76'', oil on wood.

These pieces are pre-formed reactions to the deluge of media on Syria and to the shameless lies our ruling class tells us. These images may be extra-historical caricatures. If so, they are caricatures that taunt those blood-soaked racketeers and their carrion in Washington, DC – the town where I have settled – who would find them in bad taste.

7 Tenths, 36'' x 76'', oil on wood.

Red Wedge is currently raising funds to attend the Historical Materialism conference in London this November. If you like what we do and want to see us grow, to reach greater numbers of people and help rekindle the revolutionary imagination, then please donate today.

Nicholas Avedisian-Cohen is a librarian and socialist based in DC. His paintings and videos are concerned with archiving, semiotics, and memory. His videos have been screened at Anthology Film Archives and other venues.