“Heard joke once: Man goes to doctor. Says he's depressed. Says life seems harsh and cruel. Says he feels all alone in a threatening world where what lies ahead is vague and uncertain. Doctor says, ‘Treatment is simple. Great clown Pagliacci is in town tonight. Go and see him. That should pick you up.’ Man bursts into tears. Says, ‘But doctor... I am Pagliacci.’ Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains." – Rorschach, Watchmen

It’s easy to say that it’s because of Halloween. But why this Halloween? Why not last year or the year before? Will 2016 (already an ignominious year) be remembered as the year that sent in the clowns?

If you’re willing to sift through the horror of election coverage, then it’s not hard to find, wedged into the cracks, a full on clown panic. It is nothing if not bizarre. Individuals dressed as clowns, leering at passersby, sometimes outright chasing or threatening them. It has gotten to a violent point; at least one practical joker has been pistol-whipped, another stabbed by friends. It also, allegedly, seems to have gone the other way at least once in San Diego. Still others have just been misunderstood, as happened in September when a 12-year-old autistic boy excited for his Halloween costume spooked residents of a Virginia town.

Can any significant part of this be chalked up to a threat? How much of it is just kids playing pranks versus disturbed individuals looking to do legitimate harm? How much of it is marketing gimmick or media hype? Or simply authorities inadvertently spurring what they are warning against? Do those who are now calling the cops on “lurking clowns” have actual crimes to report, or are they simply gripped by moral panic that has spun a little bit too out of control? How many or those wearing greasepaint are actual criminals, and how many have been, well, just clowning around?

I have no answers to the above questions. And frankly, I’m not all that interested in providing any. What seems a far greater interest is that, on top of everything else, we now live in a country where police are giving press conferences where they seriously address the “clown question.” Even the White House is giving briefings on the matter.

When a phenomenon – even one so absurd – is integrated into a state’s repressive apparatus, it becomes undeniably tangible. The clown phenomenon, such as it is, is an Enemy, and Enemies are always real, even if it is just in the mass imagination. Even if the clowns disappear after October the 31st, something about this moment, this odd instance where the merely subversive becomes a menace, won’t likely fade. It is, in fact, rather a part of our life now.

This, after all, is a time when the weird and the real have been inverted. Events and gestures can be ghosts well before they are actually born. Ideas both fantastic and horrible are almost guaranteed to be seized by someone and made concrete. Five years ago the Slender Man was just a viral Creepypasta. But in 2014 he took on life after two twelve-year-old girls in Wisconsin stabbed a classmate 19 times in order to impress him. Now a movie is in the works about the incident. Does life imitate art or art imitate life? Who can tell what came first? And when virtually any idea can become weaponized, does it really matter?

* * *

The term that has been coined for fear of clowns, “coulrophobia,” has not been recognized by either the American Psychiatric Association or the Oxford English Dictionary. Nonetheless, the trope of the scary clown is ubiquitous. Ironically, clowns are often perceived as off-putting and creepy for roughly the same reason that they are considered funny and sweetly entertaining. They are human, but not quite. They are certainly people, but of an exaggerated physical and emotional state. In their routines and stories they are often bound by the same laws and societal mores as the rest of us, but are imbued (either magically or otherwise) with the propensity or desire to sidestep these same limits. Clowns, therefore, are by their nature inhabitants of the uncanny valley where we see a little bit too much of our own unjust limitation reflected back to us.

Whether our reaction is laughter or horror isn’t quite as opposite as it might at first appear. Anyone who has ever chuckled during a slasher movie or zombie film (and we all have) knows this. And, fittingly, the vengeful jester or evil clown has become common in literary and popular culture. Edgar Allen Poe’s “Hop-Frog,” the jilted Canio in who slays his beloved on stage in Pagliacci, the Joker, Stephen King’s Pennywise, the tragic and simple-minded Twisty, and of course, Pogo, the real-life alter-ego of John Wayne Gacy; all of these are characters that make the humorous grotesque and obscene, playing at our own horror with the confusion between laughter and despair.

Andrew McConnell Stott, in his book The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi, insists that the tragic Grimaldi – an immensely popular British comedic pantomime actor who quite literally destroyed his body onstage – is where the trope takes root. Charles Dickens’ 1836 serial The Pickwick Papers portrays a character rumored to have been modeled off Grimaldi’s son (also a comedic actor who drank himself to death at the age of 31). The character is drunk, his body broken, his demeanor sad and tragic, starkly contrasted with his brightly outlandish makeup and onstage antics.

Artist's rendering of Joseph Grimaldi.

After the elder Grimaldi died in 1837, Dickens was tasked with writing his biography. Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi sold very well, and its portrayal of its subject was one of “strict economy.” For every joy he portrayed onstage, the real Grimaldi seemed to suffer more heartache, more tragedy. Stott credits both The Pickwick Papers and the Grimaldi memoir with essentially popularizing the image of clowns as unintentionally multidimensional, as a character whose goofy frivolity was a cover for something far darker, even sinister.

That this image began to spread at what was roughly the crucible of industrial capitalism wasn’t coincidental. Dickens’ criticism of industrialism is not difficult to find throughout his work, contrasted with his idealized portrayals of small shops and manufacturers. His Grimaldis, therefore, can be feasibly understood as illustrations of the physical and emotional toll wrought by the demands of the job underneath its façade.

Dickens, naturally, wasn’t the only one in this era to see something deceptive in industrial capitalism. When Karl Marx was formulating his analysis of capital from the 1840’s through the 1860’s, he frequently relied on the notion of the “character mask” borrowed from Greek theatre, the donning of another face for the sake of a role. But while the Greek drama required it on an individual albeit functional level, Marx adapted the concept to describe the mass ideological needs of capital.

In a fairly basic sense, this is a “two-facedness” we already recognize in truisms that are almost cliché. Politicians lie, the rich lie, major news outlets lie; all are hiding a rather crude self-interest beneath. For Marx, however, this deception wormed even more insidiously into the very core of social interaction. The segmenting and division of labor, the increasingly fractious nature of work, leisure and life, all necessitate a mask. The employee adopts the mask of the employer’s interests, conforming to the needs of authority often in opposition to their own self-interest. Our behavior and consciousness learn to express and repress certain actions and thoughts. The services and things we produce and buy begin to take on more life than ourselves, and thusly our identities are twisted around them rather than vice versa.

It isn’t a stretch, therefore, to say that Marx broadly saw in the masked performer an avatar for his own age. Like Dickens’ Grimaldi, there was a tragic dialectic in this universal figure. No matter how jolly and frivolous the mask – or the greasepaint – might be, it covers a grisly reality wrought by capital’s naked self-interest.

Come the middle of the twentieth century, there was a clear tendency away from the more complicated and layered Dickensian clown and toward clowns that were more “pure,” sweet and saccharine. Booming consumerism and growing culture industries were both aided by this one-dimensionality and helped it go down easier. But even these can be read through today’s lens as little more than a smiley face on a more painful reality. Many women and Blacks likely had a different perspective on the unbridled optimism of Bozo the Clown during its heyday. And Ronald McDonald is, of course, friendly emissary for the most recognizable symbol of American capitalism in the world, guilty of everything from ecological devastation to human rights violations. The makeup can only cover so much.

* * *

Broaden the focus on today’s world. The list of anxieties and fears both real and manufactured is too long to recount here. Drop on top of this a profoundly precarious economic reality that has achieved a dominance over our lives Marx and Dickens could never have surmised.

Not only has every aspect of American existence been monetized, it has further been twisted round, Ubered and TaskRabbitted back to us as methods of survival. “Sharing economy” is a lovely, happy phrase; the billions made from our participation in it will, however, never be shared. A more apt term would be “full spectrum exploitation,” in which the final barrier between personal life and work is finally dissolved. All labor becomes emotional, every feeling and bit of “down time” can be capitalized upon, and the schizophrenic nature of employment begins to soak into our existence on a profoundly individualized and atomized level.

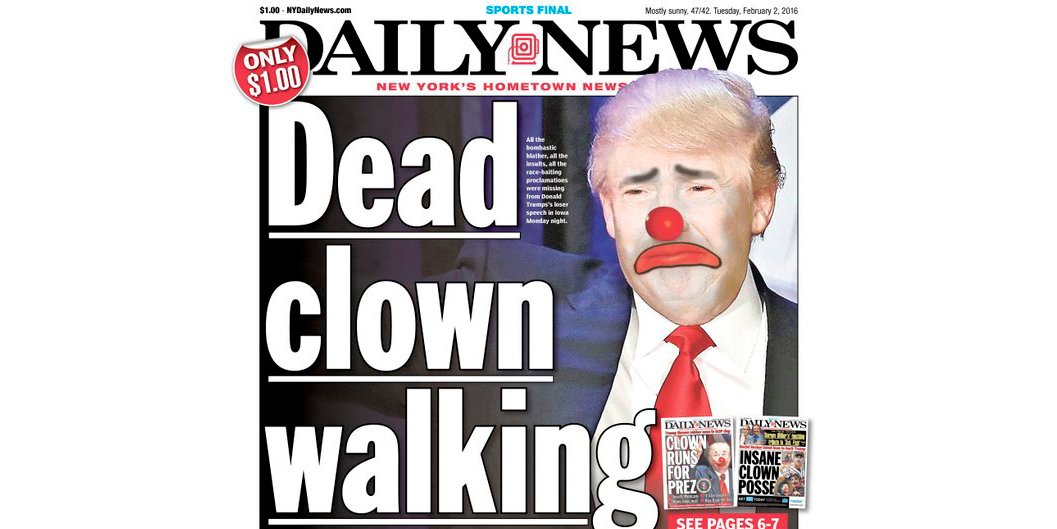

Sharper, more palpably existential anxieties cannot be organically disconnected from this economic reality. The plight of refugees, climate catastrophe, Daesh, Trumpist right-wing populism; these are all manifesting as crises in particularly neoliberal ways. Not only are they rooted at the nexus of political economy and global crises, they all seem to join the denuding of the individual’s sanity with the needs of an increasingly unhinged system which is losing the capability to rein in its more monstrous tendencies.

Much as some would love to externalize and other-ize the abject violence and senselessness of modern life from “American values,” the past year has shown how futile this is. In fact, recent events have shown just how easily an almost caricatured smile can be joined with vicious brutality. Consider the cheers that went up when Trump supporters assaulted protesters at rallies. Or the glee with which some people seem to cheer on the cops shooting Black people. Baseball fans put on racist “Indian” makeup to honor America’s pastime while actual indigenous people are arrested and have dogs sic’d on them for protecting their water and land rights.

This is a disturbing brew, one that is fairly fertile for disturbing, surreal mania. In an age when we are cheerily told to “do what we love” in the midst mass shootings, state-sanctioned violence and megalomaniac presidential candidates, it’s quite difficult to deny how apropos such manic deception is. A country delirious and punch drunk under the weight of its own threats can make the creepy clown a perfect avatar.

In Alan Moore’s famously praised Watchmen, there is a scene in which the Comedian – a masked vigilante who, despite his clownish persona, possesses an almost sociopathic love of violence – clears a street of protesters with shotgun shells and teargas canisters. His partner, Nite Owl, is despondent, lamenting the chaos and the fact that it has come to this.

“But the country’s disintegrating,” he says. “What happened to America? What happened to the American dream?”

The Comedian gleefully answers, his shotgun held high: “It came true. You’re lookin’ at it.”

Red Wedge has released our first ever digital Hallowzine, featuring past material on the spooky and macabre and design from editor Craig E. Ross, going out to donors this weekend. If you would like to have on delivered directly to your inbox, then donate to our travel fund!

Alexander Billet is a communist, writer, poet, and cultural critic. He is a founding editor of Red Wedge Magazine and currently is its editor-in-chief. His writing has also appeared at Jacobin, In These Times, and the International Socialist Review. Follow him on Twitter: @UbuPamplemousse