“Normie” socialists, having largely lost recent political arguments in the new socialist movement – particularly in the righteous backlash against Angela Nagle – seem to be redoubling their efforts on the cultural front. Jacobin recently posted two highly questionable articles along these lines; John Halle’s “In Defense of Kenny G” and Alexander Dunst’s “Graphic Novels Are Comic Books, But Gentrified.”

I am going to focus here on the latter article. Underpinning both to some degree, however, are false assumptions about the working-class and its relationship to art and culture; that its tastes are assumed a priori pedestrian or banal, that aesthetically and intellectually challenging or difficult material are beyond the ken of the proletarian mind, and that there is some sort of normative working-class (when there is not).

It should be taken as a given that a defense of the graphic novel does not mean agreeing with New Criterion-esque “high culture” criticisms of popular art forms like comics.[1] Indeed, the line between graphic novel and comic is not nearly so clear as Dunst would have it. Many graphic novels are actually compendiums of previously published comics. For example, one of the most popular graphic novels of the late 1980s and early 1990s (and ever since), Alan Moore’s Watchmen, first appeared in traditional comic form as a twelve-part series.

Interestingly, given the thrust of Dunst’s article – a would-be defense of the popular comic form vs. the evil gentrified graphic novel – there is very little about the substance or history of actual comics. This mirrors the fact that Dunst, after invoking gentrification as an abstract criticism (rather than an actual process involving social relationships), references titles like Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, but spends no time discussing the actual content of said work.

from Art Spiegelman’s Maus

Maus tells the story of Spiegelman’s family during the Holocaust, through the frame of the artist interviewing his father, a survivor from Poland. It does this, famously, in an irrealist manner. Jews are presented as mice; redirecting the Nazi presentation of Jews as rats and vermin. Germans are presented as cats. Poles as pigs. And so on. Of course one might criticize Spiegelman’s approach to the subject, but that is not what Dunst does. The actual content of Maus appears to be a non-question. It is a graphic novel, and, therefore, suspect or condemned.

Maus

Spiegelman cut his teeth in the underground comic scene of the long 1960s – often tied to the new alternative weeklies[2] that mushroomed in most major US cities. Spiegelman co-edited the comics anthology Raw, which, along with Robert Crumb’s Weirdo, was one of the main publications of underground comics. There were many things to criticize in this movement; particularly the casual sexism and misogyny of many of its artists. At the same time, however, it was an avenue of expression that often allied itself with the liberation struggles of the time, albeit in an incomplete way. These underground comics and weeklies gave a platform to artists who might never have had one otherwise, including many queer artists and artists from poor and working-class backgrounds.

Maus

Moreover, again contradicting aspects of Dunst’s gentrification schematic, Maus was originally serialized, not as a graphic novel, but as a regular feature in Raw. Similarly, Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, also cited by Dunst as part of the comic gentrification problem, was syndicated for years in free weeklies.

Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan

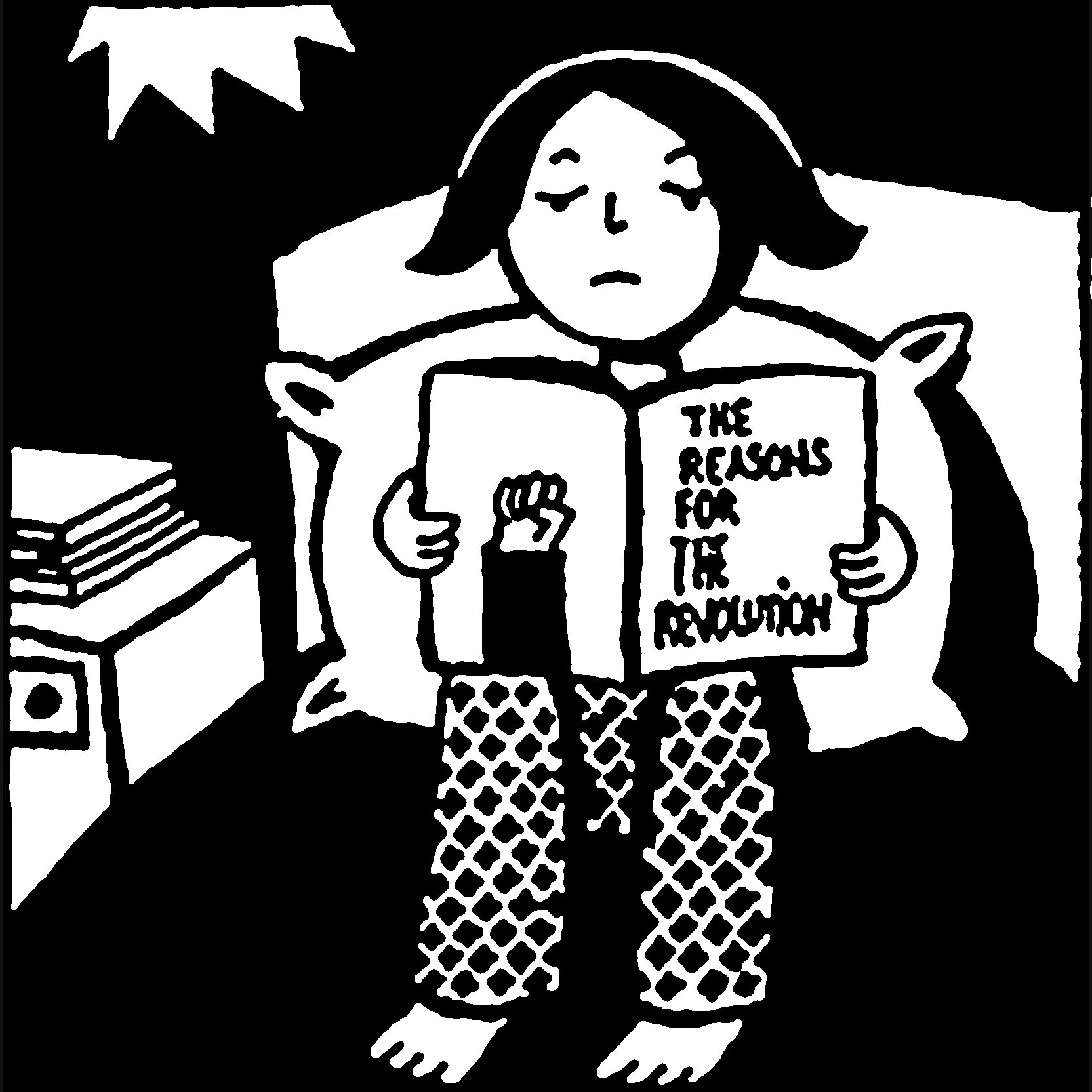

Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, a two-part graphic novel that was adapted into an animated film, tells the story of the author growing up in 1970s Iran, the persecution of her family and family friends (intellectuals tied to the Communist movement), the hopes raised by the 1979 Revolution, its take-over by the Islamic Republic, the resumed persecution of her family, and the accelerated persecution of women, and so on.

Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis

Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis

Julie Maroh’s Blue is the Warmest Color, also mentioned by Dunst, tells the story of two women in love in 1990s France. Allison Bechdel’s memoir Fun Home is also cited. Bechdel, the author of Dykes to Watch Out For, is perhaps most famous outside of comics for the feminist Bechdel Test for film and television shows.

Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For

If you are beginning to see a pattern in the work that Dunst has singled out…

It is almost beyond belief that a socialist publication[3] would publish an article that attacks the memoir of a red diaper baby in revolutionary Tehran, or the story of a Holocaust survivor, just because they are told in “graphic novel” format, or the work of feminist and lesbian artists, without ever examining the actual content of those artworks. If anything, given the threats of fascism today and the exploding fights in Iran against austerity, even at a base practical level we should be encouraging comrades and our working-class siblings to read these works. Instead, Comrade Dunst has put forth what seems like a bad faith argument for the crudest approach to media possible.

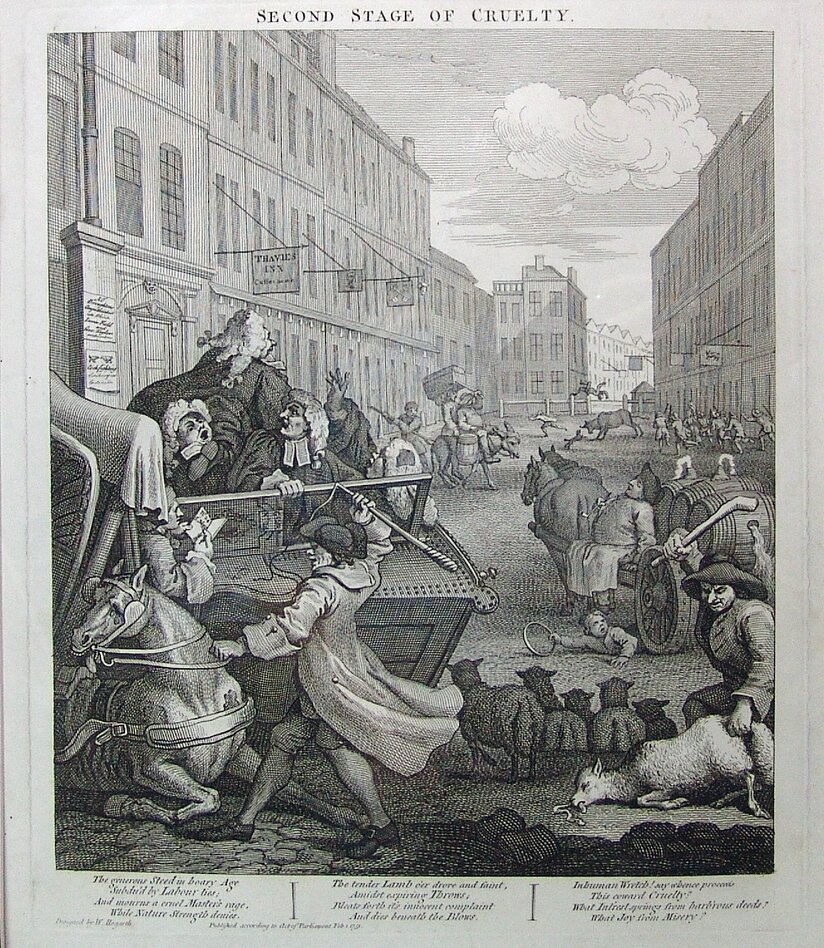

William Hogarth, The Four Stages of Cruelty, Plate 1 (1751)

William Hogarth, The Four Stages of Cruelty ,Plate 2 (1751)

William Hogarth, The Four Stages of Cruelty , Plate 3 (1751)

William Hogarth, The Four Stages of Cruelty, Plate 4 (1751)

If Dunst flattens and ignores the content of the graphic novel, he also flattens and ignores much of the history of comics themselves. While admitting the sexism and racism of many Golden and Silver Age comics, Dunst seems largely unconcerned with popular counter-traditions within comics, the history of comics before the 20th century, or the contradictory anti-fascism of early Marvel and DC titles (often pioneered by Jewish artists and writers).[4]

From Junji Ito Uzumaki (1988-1999)

These publications all have a contradictory class history. Early modern European “sequential visual narratives” — what comics essentially are — were oriented at more middle and upper-class audiences who could afford the limited print runs of the time. Middle-class artists like William Hogarth tended to critique both the upper and lower classes from a moralistic point of view. As cheaper and more efficient means of printmaking became more widely available early comics developed a wider working-class audience, particularly before literacy became universal in wealthy nations. Japanese manga, while enjoying a wide proletarian audience today, have roots in more and less egalitarian markets, including but not limited to the market for prints among middle and upper class visitors to the vice-houses of “floating world” Edo-period Japan.

EC Comics, “Taint the Meat”

Of course, Dunst does not mention the short lived history of EC Comics, the US publisher that continued to create, more or less, Popular Front narratives after WW2 (until they were shut down under threats from the Comics Code Authority). EC Comics, which published horror, science fiction, crime, war, and other pulp genres, was influenced by Emile Zola’s ideas of naturalism. Zola, himself influenced by the mass struggles of the French working-class in the 19th century, developed an approach to literary realism that emphasized the external constraints on narrative subjects. In other words, these comics, like the work that inspired them, often told working-class stories, and stories of the oppressed, albeit in pulp form, in a way that emphasized both the characters’ psychological reality as well as the horrors of racism, capitalism and war. EC Comics had a large influence on future writers and filmmakers like Stephen King and George Romero.

The final page of EC Comics, “Judgment Day”

Dunst’s criticisms don’t even hold up mathematically. The key part of the gentrification process for capitalists is, of course, double: a payday, and a reshaping of urban space. The point of gentrification isn’t really to create aesthetic forms that alienate working-class people. That is a tool and byproduct of the process. The point of gentrification is to price working-class people out of neighborhoods in order for landlords and developers to make a profit while changing the class composition of a city.

So, let’s look at the price of some graphic novels and compare those prices to regular comics. The Watchmen costs, at present, $14.99 on Amazon. A single regular comic will cost between $2.99 and $5. But, remember, The Watchmen is a collection of twelve previously published comics, which makes its graphic novel format actually cheaper. Maus costs, at present, $18.89 on Amazon. Persepolis costs $14.49. Perhaps the price of these commodities is too much for Dunst. I am happy to loan him my copies of these artworks so he can actually read them before his next “hot take.” But, prices aside, maybe Dunst has a point about audience. He asserts that graphic novels are not as popular as previous iterations of comics. But Persepolis has sold more than two million copies. The Watchmen is one of the most popular comics of recent decades. Maus has sold 1.8 million copies in the United States. Perhaps everyone who bought and/or read these was hopelessly middle-class.

Leonard Freed, Residents of Guernica in front of a mural replica of Pablo Picasso's painting (1977)

But is this the main criteria by which comrades should judge art? The initial audience for most of Picasso’s work was middle or upper-class. But Picasso loaned his painting Guernica to the antifascist effort during the Spanish Civil War. The painting was toured, mostly among working-class audiences, to drum up support for the antifascist cause. It became indelibly linked in social consciousness with the fight against fascism and war.

There are two points in Dunst’s article that are more worth discussion. One, what is the relationship between aesthetic co-optation to capital and gentrification? Two, the question of individual subjectivity that he touches on when dealing with the question of the memoir-form.

Artists – including working-class artists from areas targeted by gentrification – have repeatedly been used (and then usually discarded) in the process of gentrification. This is a real challenge, especially for working-class and socialist artists who rightly want to make art for their communities while avoiding complicity with the gentrification process. The answer to this, however, isn’t pearl clutching economism (reducing all politics, let alone art, to economic / class issues). Art and literature are disciplines that are, of course, political. Similarly, science is always political. But art, like science, has its own dynamics. There are, for example, justified criticisms to make of Margaret Atwood – particularly around the Steven Galloway controversy. Winning a literary award, generally speaking, isn’t one of them. It is not unlike, all things being equal, criticizing a botanist for winning a botany award.

Indeed, at many points Dunst sounds profoundly anti-intellectual. Instead of the classical socialist idea of “the fusion of science and the working-class,” Dunst seems to take a position inherently hostile to anyone who has dared earn a degree in anything, assuming that all scholars are middle-class, and that, therefore, their point of view is suspect.[5] The first half of this assumption would have tracked forty years ago, but after the adjunctification of academia (at least in the US) it is almost laughable. The second half of his assumption is itself problematic. Serious arguments need to be addressed in terms of their actual content; not the assumed class identity of the person making the argument. This is not to say class position is irrelevant. Nor is it to say we should take the arguments of a foreman or manager seriously until we “unpack them historically and theoretically.” But the argument of a factory foreman or store manager is not the same thing as the informed arguments of a humanities scholar, who, these days, may or may not be living in her car.

The above is, of course, related to the argument that Dunst raises early in his article, but doesn’t unpack, about the collapse of “high” and “low” art categories in neoliberal capitalism. We’ve discussed this at length in Red Wedge so we won’t unpack it much here; except to tease out a few points.

The fluidity of current cultural forms is related to what Marxist cultural critics call reification (which, in this case, means to make the concrete abstract). This means that cultural gestures, images and stories meant to be critical of capital, or meant to expose the truth of daily life under capitalism, etc., become separated over time from their context and social origins and therefore their original meaning. Within a few years, early punk and Hip Hop gestures, sounds, and images, often meant to be critical of capitalism and racism in their original context, were translated into advertisements for things like soda pop and sneakers. At the same time haughty art galleries showed art from some of the New York graffiti artists who pioneered “Wild Style” in the 1970s. The meaning of the original graffiti tag, a literal claiming of space by working-class youth, often youth of color, was totally lost in the gallery context.

Image from the Charlie Ahearn’s 1983 film Wild Style

The specific collapse of “low” and “high” art is a product of many additional things, beyond but related to reification. First of all, the collapse was partly the product of capitalist victory in a long cultural war with pre-capitalist aesthetic forms – the art of aristocrats and the church in particular. In other words, the culmination of art becoming, first and foremost, a commodity. Secondly, mechanical (and then digital) reproduction made a mass popular culture possible. The ideological champions of the high/low collapse in the academy used this as a populist cover for a politics that, in effect, minimized the importance of social class. This was usually called post-modernism. While it seemingly tore down the pretentions of elitist art, it also gutted art, replacing any concerns for underlying dynamics of narrative and image with a profoundly superficial, but nonetheless verbose, approach to the subject matter.

It is when Dunst argues that the memoir form is inherently middle-class that he finally makes what I consider to be his “real” point. It is a profoundly backwards point. Dunst is saying, basically, that individual subjectivity, individual expression, individual personal history, are alien to working-class life, or that workers aren’t interested in these matters, or shouldn’t be.[6]

Is it because of his distrust of individual subjectivity – the personal identity and psychology of the main character/author – that Dunst seems to ignore the communist elements of Persepolis? Dunst talks about a blindness to social class. There is literally a revolution – made initially in large part by the Iranian working class – in Persepolis. Dunst doesn’t even mention this in his article. Did he read the book? Did he intentionally conceal this information to benefit his polemic?

Persepolis

Ignoring the content of these artworks has reactionary implications that Dunst has probably not considered; or has considered but ignored in an attempt to gaslight his readers. In the way he has written this article, the horror of the Holocaust, the repression of our Iranian comrades, homophobia, are all dismissed as an “obsession with personal identity.” One has to wonder if the problem with these texts and images, for Dunst, isn’t that they are memoirs, but that they are the stories of people who are gay or queer, aren’t white, or whose whiteness is contingent.

Persepolis

I can’t speak to whether or not this was Dunst’s intent. But his clearest intent was bad enough. It was to argue, in a socialist publication, that working-class people either don’t care about identity and self-expression, or are unable to navigate these subjects, or shouldn’t consider them. In other words, Dunst’s version of socialism would deny working-class people the full fruits of art and culture and the full fruits of self-determination and creativity. The Marxist poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht responded, in his debates with George Lukács, to this kind of faux proletarianism:

Even those writers who are conscious of the fact that capitalism impoverishes, dehumanizes, mechanizes human beings, and who fight against it, seem to be part of the same process of impoverishment: for they too, in their writing, appear to be less concerned with elevating man, they rush him through events, treat his inner life as quantité negligeable and so on...

Dunst’s profoundly anti-working class bias, despite his claims of the opposite, should be clear in his static view of working-class taste and his conflation of “working-class” and “juvenile” audiences. I can almost hear a voice, in a fake “working-class” accent, saying that “them-there-workers don’t want to hear about no damned revolution in Iran or no gall darn Holocaust. Give em Batman. That’s what workin peeples want!”

p.s. fuck Batman and the fascist Batmobile he rode in on; except for campy 1960s Batman. That was good.

Endnotes

[1] The New Criterion is a conservative cultural journal born of the 1980s culture wars based in New York City.

[2] The eventual relationship between these alternative weeklies and gentrification – which Dunst doesn’t actually discuss – is important. As the struggles of the long 1960s waned in the 1980s many of these weeklies took a profoundly backwards position on gentrification, particularly the Village Voice in New York City; although the Village Voice also published anti-gentrification articles. This was even more contradictory as many of these publications continued to take far more left-wing stands on other matters. Nevertheless, they grew reliant on advertising revenue and tied to the gentrification process on a material basis. Most of these publications themselves succumbed to the crisis of print media in the 2000s. Some of the surviving weeklies, like the Seattle Stranger have championed figures of the new socialist movement – like Kshama Sawant – fighting gentrification.

[3] While Jacobin bears responsibility for posting these articles – this criticism is not meant to be another left attack on Jacobin for the sake of another left attack on Jacobin. Agree or disagree with the journal’s political lines, the quality of most Jacobin articles is far superior to this embarrassing tract.

[4] For a good introduction to comics as an art form read Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics.

[5] It should be noted here that Dunst is himself an academic – of course – who teaches cultural history at Paderborn University in Germany.

[6] This is not to say that the majority of published memoirs aren’t, in essence, self-hagiographies of bourgeois and petit-bourgeois figures, usually white men. They are. But this does not mean ipso facto that the memoir form itself is inherently bourgeois. It is the denial of subjectivity to the working-class and oppressed that is the problem, not the existence of subjectivity itself.

Adam Turl is an artist and writer from southern Illinois (by way of upstate New York, Wisconsin, Chicago and St. Louis) living in Las Vegas, Nevada. He is an editor at Locust Review, the art and design editor at Red Wedge and an adjunct instructor at the University of Nevada - Las Vegas. He is currently working on the Born Again Labor Museum project with fellow artist and writer Tish Markley. Their website is evictedart.com.