“What did you want – a cliff over a city?

A foreland, sloped to sea and overgrown with roses?

These people live here” – Muriel Rukeyser, “The Book of the Dead”

In 2015 it became clear that Viktor Shklovsky’s imperative to “make the stone stony” is a much simpler task than “making the corpse corpsely.” I am thinking of the use of autopsy transcript as poem, Kenneth Goldsmith’s appropriation of the shooting death of Michael Brown. [1] While this particular text was said to be uniquely parasitical and vampiric, likely as much for its arrogance as its form, it should be understood as the logical product of an aberration in American documentary poetics that has recently adopted the brand name “Conceptualism.” Goldsmith’s personal framing of Conceptualism holds that all that must be written has been written and must merely be re-packaged: “The world is full of texts, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more.” [2]

A maximalist take on a now commonplace idea that demands the equally commonplace response, “what relationship exists between the texts and the writer?” And the more immediate question, “who, then, do the texts serve?” The answer to these questions is at the core of the struggle to develop a documentary poetics adequate to our new and increasingly textual world.

I will say plainly that I believe Conceptualism’s sole answer is essentially surrender. For the Conceptualist, left almost entirely without initiative, there is no choice but to become wholly reactionary – making their names almost exclusively by usurping not only individual tragedies, but history itself, as if the events they reproduce emerge from a divine absence.

Kenneth Goldsmith.

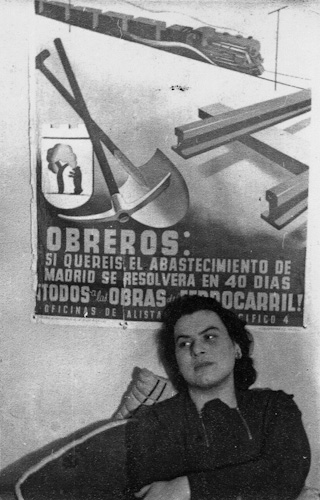

This is not to say that engagement with documents, appropriation, or the use of “found texts” is, in and of itself, incorrect. As we become increasingly steeped in infomedia, rhetorical products, social networks, and “immaterial” goods of all stripes, the question of the document becomes a legitimate and potentially vital consideration in any artistic project. With these technological and financial innovations perceived as the bedrock of a new mode of globalized production, the question takes on a profound political significance as well. In this atmosphere of urgency, two antagonistic and irreconcilable paths have developed [3] – one, the neo-liberal “pure appropriation” of the Conceptualist, and the other represented in a new strain of radical poetics which draws its inspiration from such counter-traditions as communist theories of reportage and Literature of the Fact. It should be obvious that I align myself here with the Reds.

To describe the enemy:

In his text Immaterial Labor, the sociologist and philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato writes that contemporary “Post-Fordist” production is not merely the production of goods, “but the multiplication of new conditions and variations for production itself… Consumption in turn gives rise to a consumer who does not merely devour, but communicates, who is ‘creatively’ engaged.” [4] The result is what Virno calls the “communism of capital,” the commons of immaterial production, and, finally, “production for production’s sake.” Compare this concept with Vanessa Place’s theses on allegorical and appropriative writing in her “Notes on Conceptualisms” and you will see a clear symmetry:

The primary function moves from production to post-production. This may involve a shift from the material of production to the mode of production, or the production of mode. [5]

Compared side by side it is easy to draw the conclusion that Conceptualism finds its inspiration and natural home in the neo-liberal logic of our contemporary economy. Situated comfortably in this new marketplace, there is a necessity for the Conceptualist poet to “buy in” to the transformative possibility in this “communism of capital,” and so, logically, they mimic its techniques. Appropriation and an emphasis on choice of medium (especially mediums that are hyper-current and digital, as in Snapchat poetry) become the obvious mechanisms for literary production and the document - its raw material. The artist, like the modern info-worker, learns to curate tastes rather than products. At the same time, this type of writer positions herself as the conduit between the banal and the sublime – another act of privatization of the commons and a gesture that makes the Conceptualist look more like an antiquated Romantic rather than something postpost-modern.

And like this - Conceptualism and the New Economy are conjoined. Just as Alan Greenspan can offer the phrase “irrational exuberance” and dictate not only the perception, but the real prescience of investors, Kenneth Goldsmith can say: “I always massage dry texts to transform them into literature, for that it (sic) what they are when I read them.” [6]

Both have made the production of fact, thus of reality, and thus of literature a matter of a simple utterance. Poetry operating under this mantra can function as nothing more than an “archival machine” which hoovers up and spits out the most pop formulations of inert and disarmed language, and can find as its justification an appearance of contemporaneity in the shadow of the market. Each time the marketplace reveals its expansive power, so too does the Conceptualist method seem to prove its strength. Even now the cry goes up, “Three cheers for the diffuse factory!”

But woe to the cognitariat! – and to all those who see in it some kind of redemption, an ennobling proletarianization. Even Hito Steyerl cannot resist comparing the artists of today to the “shock workers” of the Soviet Union. [7] But we should recognize that reproducing the conditions and struggles of contemporary life does not, in its own right, make conceptual writing (or any artwork for that matter) critical, nor does it make it masterful. After all, to be proletarianized under a revolutionary “workers” ideology means something much different than it does in the context of a dominant and massively global private economy. For this reason, it is of use to look backwards at the origins of American documentary poetics, and the political avant-garde which it circumscribed.

Muriel Rukeyser.

The 1938 cycle “The Book of the Dead,” written by Muriel Rukeyser and contained in her collection US 1, was one of the first canonical works in American documentary poetry. The cycle deals with the death of scores of laborers in West Virginia due to silicosis and gross neglect during the construction of a tunnel servicing the Gauley Bridge hydroelectric project, an event that was still playing out in national headlines at the time. A contributing writer to New Masses, The Daily Worker, and a witness to the dawn of the Spanish Civil War, Rukeyser was an unabashed leftist poet. And as a leftist poet, she had a natural awareness of poetry’s historical weakness: its over identification with the poet him/herself regardless of its subject. Recognizing this inherent poetical limitation, Rukeyser felt a powerful need to address the overt subjectivity and self-indulgence of the lyric poem in her maturing work. Documentary form and the practice of reportage, as inaugurated by John Reed’s Ten Days That Shook The World, in the West and LEF in the Soviet Union, became obvious tools for the “reconciliation of her position as an intellectual and her allegiance to the working class.” [8]

It is this solution that produced “The Book of the Dead,” which makes use of the document (whether congressional testimony, interviews, correspondence, or stock prices) as a powerful form of Brechtian estrangement. Their immediate effect is to subordinate her poetry to historical fact and not her personal mythology, and to unite the lyrical elements of her poetry with the dramatic and the epic – with a collective vision. The section “Mearl Blankenship,” for example, demonstrates the intersplicing of Muriel Rukeyser’s own voice with documentary evidence – the words and writing of an afflicted worker:

He stood against the stove

facing the fire –

Little warmth, no words,

loud machines.Voted relief,

wished money mailed,

quietly under the crashing:“I wake up choking, and my wife

“rolls me over on my left side;

“then I’m asleep in the dream I always see:

“the tunnel choked

“the dark wall coughing dust.“I have written a letter.

“Send it to the city,

“maybe to a paper

“if it’s all right.”Dear Sir, my name is Mearl Blankenship.

I have Worked for the rhinehart & Dennis Co.

Many days & many nights

& it was so dusty you couldn’t hardly see the lights.

I helped nip steel for the drills

& helped lay the track in the tunnel

& done lots of drilling near the mouth of the tunnell

& when the shots went off the boss said

If you are going to work Venture back

& the boss was Mr. Andrews

& now he is dead and gone

But I am still here

a lingering alongHe stood against the rock

facing the river

grey river grey face

the rock mottled behind him

like X-ray plate enlarged

diffuse and stony

his face against the stone [9]

By rejecting self-identification with the lyrical subject, Rukeyser offered a powerful rebuke to the Romantic conception of poetry as the portrayal of inner life, and the Romantic conception of history as a chain of events through which the individual (the artist) may gain more varied and unique cathartic experiences. But this polemic is characteristic of the Modernist project as a whole, visible in Pound’s politically fascist Cantos just the same as in the tradition of the aesthetical left. The differentiation and specific development unique to Rukeyser lay in her ability to surpass the mythological quality of writers like Pound by uniting the epic-objective (in the form of raw statistics, facts, and reports) with the dramatic (in the form of interviews, testimony and letters). It is this conceit in documentary poetics that can allow lyric to merge with rhetoric, and therefore to become capable of conflict, of ideological argument on the field of history rather than sentiment.

We can see the further development of this strategy in the work of the Moscow based poet, playwright, philosopher, and theorist Keti Chukrov. Chukrov’s writing often takes the form of dramatic poems with every day contemporary Russian scenes as their backdrops. Into this staging she introduces characters who interact primarily in verse, most recognizable as clearly delineated “social types” or the embodiment of a specific theoretical tendency – as in the Post-Humanist bio-robot Paco in her video piece Love Machines. The skeleton of her cast becomes, then, documentary: a host of re-purposed tracts, streetside banter, popular opinions, political screeds, poems, and art-historical tropes. Chukrov animates her players with the generally unattributed language of other actors.

From Keti Chukrov's Love Machines.

Through this convention the documentary gesture is removed from authorial ownership – and re-appropriated in its role as a social tool. Yet, the characters themselves are prevented from becoming bare bones archetypes through their lyricism, their verse, which corrodes the mold of their assigned language and makes them flesh. By inverting the gesture of appropriation (that is by showing how society appropriates), it is not the poet who stages a monologue, but the shopkeeper, the performance artist, the young Marxist theorist. And by setting all that the document contains in a vessel that lives and breathes, be they actors or poetic constructs, Chukrov shows that it is possible to suggest their trajectory and to reveal the inevitable clashes and intersections that ensue. In this framework, Hamlet can be recast as the petty lord of the Afghan Kuzminki market and an artist disguised as housepainter can be given the name Diamara (short for dialectical materialism) to juxtapose the language of antique Marxism with the proverbs of the nouveau riche. Or, as in Love Machines, a young leftist intellectual can discover the limitations of his role as “knowledge worker” when the bio-robot Paco demonstrates the materiality of the world simply by soliciting a blowjob in exchange for a spot at a prestigious London Conference. Set in motion these vessels become not only lyrical subjects, but carriers and partisans of something akin to an opening of the archive.

This embodied commons is what the privatizing logic of Conceptualism ultimately cannot understand or engage with. For every abstracted phenomenon of the New Economy, for every new mode of production, for every “twitter revolution,” enmeshed in the mechanics there is a mass of interconnected bodies that sweat, laugh, fuck, and speak in real time – in new and sometimes prescient combinations.

Endnote

- In March, 2015, Kenneth Goldsmith read a “re-mixed” version of Michael Brown’s autopsy report at the Interrupt 3 conference at Brown University. It was entitled “The Body of Michael Brown.”

- This too is purloined from a 50 year old quotation by the conceptual artist Douglas Huebler, "The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more." Kenneth Goldsmith. Being Boring. http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/goldsmith/goldsmith_boring.html

- Of course there is a much larger ecology than these two tendencies, but they embody a conflict between left and right wing that will have important repercussions for writing and the arts in contemporary “networked” conditions.

- Keti Chukrov. “Towards the Space of the General: On Labor beyond Materiality and Immateriality”. e-flux. http://www.e-flux.com/journal/towards-the-space-of-the-general-on-labor-beyond-materiality-and-immateriality/ This is Keti Chukrov paraphrasing Maurizio Lazarrato’s article Immaterial Labor. I have carried over her own description because it so neatly and succinctly parallels the following quotation of Vanessa Place.

- Vanessa Place. Notes on Conceptualisms. Ugly Duckling Presse, 2013.

- Kenneth Goldsmith. “Kenneth Goldsmith Says He is an Outlaw”. Poetry Foundation. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2015/06/kenneth-goldsmith-says-he-is-an-outlaw/

- Hito Steyerl. Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy. e-flux. http://www.e-flux.com/journal/politics-of-art-contemporary-art-and-the-transition-to-post-democracy/ Steyerl, it should be noted, deploys the term critically and specifically in the context of the art market, but even the simple conflation has dangerous/questionable implications, especially for the way artists conceive of themselves as political actors,

- Paula Rabinowitz. They Must Be Represented: The Politics of Democracy. Verso, 1994.

- Muriel Rukeyser. A Muriel Rukeyser Reader. W.V. Norton & Company, 1994.

Red Wedge has produced a special edition poster for this election of American demagoguery, featuring text adapted from Charlie Chaplin's The Great Dictator. If you would like a digital or hard copy then donate to our travel fund!

Matthew Whitley is a writer and poet whose work has appeared in publications and journals including The Brooklyn Rail, Translit (St. Petersburg), Matter, Vanitas, Kunstverein NY, Gigantic Sequins, and The New Museum’s New City Reader. His writing has also been published in the exhibition and conference context, including the recent Artspace exhibition Vertical Reach: Political Violence & Militant Aesthetics and Yale’s “Red on Red” conference, as a part of their Utopia After Utopia research initiative. Politically, he is active within the committee Rojava Solidarity NYC, supporting the communalist revolution in northern Syria. He currently co-edits the radical artists’ imprint Cicada Press with Anastasiya Osipova.