Bob Dylan has won the Nobel Prize for Literature. His name had been occasionally mentioned as a possible nominee in the past decade or so, but he was seen as unlikely to win for two reasons. The obvious one is that as a singer-songwriter rather than a published novelist, playwright or poet, his work has stood outside mainstream notions of what constitutes “literature” for most of Western establishment opinion, although the Nobel did, long ago, honor Winston Churchill for his works of history.

The second reason this was unlikely is that Dylan is American, and therefore, as we know from a gaffe years ago from a ranking member of the Swedish Academy, a provincial. Now, while I think it is somewhat ironic that members of an institution whose own country seems to take no notice of what happens outside the frontiers of Europe and which hosts one of the largest far-right movements on that continent will lecture to Americans about provincialism, under normal circumstances I would agree that an American should not receive literature’s highest honor – there are far too many fine authors of the global South, in its own languages especially (Ngugi wa Thoing’o comes to mind) who neither American nor Swedish provincials seem to take any account of.

Nevertheless, I think this is a fortunate choice. It is a recognition, even if it is not to be followed up with concrete understanding and action, that literature includes more than what is deconstructed in academic seminars, and that works like Dylan’s not only have a rhetoric that is different in style, but no less worthy than the Western canon, and which strike millions of people who may never read Philip Larkin as their first, basic, and enduring experience of poetic power. It is also a belated recognition of the American traditions that went, often unacknowledged, into Dylan’s songs over decades – labor and the Popular Front, civil rights gospel, and weird, apocalyptic country to name a few – having a relevance to the world that few would rate as being part of a global cultural heritage.

The middlebrow literary establishment in this country, as may have been predicted, has completely failed to understand the significance any of this. Jody Picoult, who I think it is safe to say deserves not the lowest literary prize in the US much less any other kind of cultural recognition, has said that if Dylan can take the Nobel, she might as well be nominated for a Grammy.

The naïve activist archetype of “Blowin’ in the Wind” is probably how any American kid first encounters the many-faced man that is Bob Dylan, and it’s him I mostly want to talk about. Though artists of the movement are only rarely protagonists of it as well, when you listen to songs like “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” it is hard to doubt either his passion or commitment to a cause larger than himself, the civil rights struggle during the most heroic of the King years. The legacy of that period is such that it is rarely remembered that Dylan himself appeared at the March on Washington to play, without comment, two songs, “Blowin’” and “Only a Pawn in their Game.”

The latter is an interesting song, and a much subtler beast than it is frequently given credit for. On the surface, it is about the assassination of Medgar Evers, drawing the elementary lesson that Southern society deliberately divided black people from poor whites, who are trained from childhood to know “you’re better than them/you’re born with white skin,” while their contempt for blacks was the secret of why “the poor white remains/in the caboose of the train.”

“They divided both to conquer each” is, of course, a basic truth, but one that can be lead to functionalism if left on its own. What is stunning about Dylan’s song is that it transcends this as a polemic. The end of the song explicitly disturbs any complacent conclusion that the fact that “he can’t be blamed” is all that’s important:

“Today, Medgar Evers was buried from the bullet he caught

They carried him down as a king

But when the shadowy sun sets on the one that fired the gun

He’ll see on his grave, on the stone that remains

Carved next to his name, his epitaph plain:

‘Only a pawn in their game.’”

The murderer of Medgar Evers, who is never named in the song (in part because, being a member of the same cult that produced the Aryan Nations, he was not a mere pawn), has made his choice. In contrast to the highest sacrifice made by his victim, all that is significant about the killer, all that will be remembered, is that he stood in as a tool for forces beyond his understanding. He is a truly pathetic creature, and more so because he did not have to be this way.

Dylan’s first of many self-transformations began in 1964, when he openly renounced his past in folk music, the civil rights movement and other progressive causes, although he did not abandon his disgust with racism (see “Hurricane,” his song about Ruben Carter from 1976.) His position within the movement had always been contradictory. On the one hand, as an artist, he could intuitively understand the basic conflict and amplify it in words that millions could hear. On the other, as a sympathizer, and a peripheral one at that, he could easily fall into cynicism at the sight of a major setback, or the simple realization that true liberation is a slippery creature that constantly wriggles out of the hands of social movements under class society.

“My Back Pages” is the form that renunciation takes. It has long been my favorite Dylan song, which I admit is an odd choice for an avowed Marxist. In particular:

“A self-ordained professor’s tongue, too serious to fool

Shouted out that liberty is just equality in school,

‘Equality,’ I spoke the word as if a wedding vow,

But I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.”

“Equality in school” is integration. We can see how Dylan, much like many of the black radicals of his age in the movement, was coming to realize that integration, as much as this or that form that American capitalism could deliver, did not equal liberation, and in fact that its achievement when placed against the barbarity inflicted on black people by the same system was rendered an irrelevance.

Dylan’s response in “My Back Pages,” however, is not the political crisis leading to further radicalization, as experienced by Stokely Carmichael, James Forman, and Muhammad Ali, it was transformed in his lyrics into a moral and existential one. “I aimed my hand at the mongrel dogs who teach/Fearing not that I'd become my enemy in the instant that I preach.” He was all of 23, and had discovered that political activism and belief itself was useless. As Mike Marqusee asks us, “Was anyone ever as quickly, or as tenderly disillusioned as the young Dylan? And was anyone ever as arrogant?”

Dylan’s apostasy from the left, then as now, is hard to take without a great deal of anger at his privilege. But in fact his overwrought, preening anger at the movement is educational. It’s hard to believe, after all, that so eloquent a fuck-off could be penned by someone to whom the movement meant nothing. Cynicism is sometimes, including here, a way of telling just how much he believed, and how bitter was his disappointment. Here, his trajectory is similar to Haruki Murakami, another once-radical artist who retreated from politics into youthful pessimism.

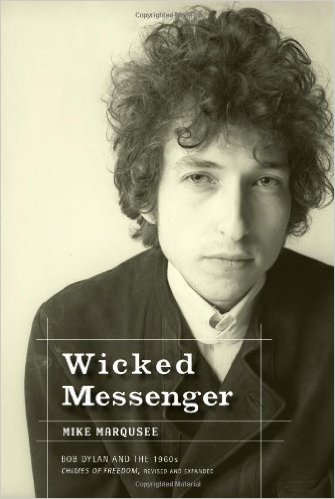

Rather than continuing to stretch my nonexistent credentials as a music critic past their breaking point, I should conclude this by leaving the last word to Marqusee, whose chronicle of Dylan in the sixties, Wicked Messenger, I recommend to any and all.

“No song on 'Another Side' distressed Dylan's friends in the movement more than 'My Back Pages,' in which he translates the rude incoherence of his ECLC rant into the organized density of art. The lilting refrain – 'I was so much older then/I'm younger than that now' – must be one of the most lyrical expressions of political apostasy ever penned. It is a recantation, in every sense of the word. Usually, political apostates justify themselves by invoking the inevitable supersession of youth and rebelliousness by maturity and responsibility... Dylan reverses the polarity. The retreat from politics is a retreat from false and stale categories and acquired, secondhand attitudes. The antidote is a proud embrace of innocence and spontaneity. The refrain encapsulates the movement from the pretence of knowing it all to the confession of knowing nothing. [...]

It's a cry of disorientation – and an acceptance of that condition in defiance of others' expectations. Yet in this song of recantation, there is also continuity. The inadequacy of liberal responses to America's growing social crises is the premise as much as it is in “Hattie Carroll.” And the assertion of youth's right to speak out – from 'Let Me Die in My Footsteps' to 'The Times They Are A-Changin’' – s extended and deepened. Youth must reject the categories inherited from the past and define its own terms. Indeed, youth itself has become the touchstone of authenticity. A tremendously empowering notion for the generation whom it first infected, but also, it turned out, a cul-de-sac, and less of a revolutionary posture than it seemed at the time."

Red Wedge is currently raising funds to attend the Historical Materialism conference in London this November. If you like what we do and want to see us grow, to reach greater numbers of people and help rekindle the revolutionary imagination, then please donate today.

“Pink Palimpsest” is the occasional blog/column on literature and film from Bill Crane, a somewhat odd American socialist living in London.