The uses and abuses of Rosa Luxemburg as a revolutionary icon are many, and they tend to focus excessively on the tragedy of her death or on her intellectual relationship with Lenin. Old Stalinists display great alabaster busts that disfigure her as a mute, empty eyed martyr to the cause of the mass murderer with whom she shares a bookshelf. Far worse than irrelevant or instrumental, the left has managed to render one of the most magnetic, vivacious and daring of its intellectuals as boring. Consequently the most exciting thing about, Red Rosa, Kate Evans’ graphic biography of the Polish-born German revolutionary is that when she undertook this extremely ambitious project, she scarcely knew anything about her:

I had very little idea who Rosa Luxemburg was…Oh, she’s one of those people I’ve vaguely heard is groovy, like Bakunin or Emma Goldman. I should really get around to reading them. I agreed to the proposal immediately. And only then did I google her, and discover what an amazing project I’d taken on.

Evans has had to build a picture of her subject from the ground up, and she is refreshingly frank about the limited information available about Luxemburg’s early life – the “fragments” from which she has had to assemble a foundation for her “fictional representation of factual events”. None the less a vibrant, tangible character emerges out of that uncertainty and the key to this is the author’s focus on Luxemburg’s personal letters over Evans’ (none the less substantial) reading of her polemic or the research of other writers. This is a great virtue in a primarily visual medium. Rather than reproducing the public persona of the revolutionary and fastening the voice to it like captions on a still photograph, it seems to me that Evans’ has looked for the voice of Rosa and constructed her representation outwards with that voice as its foundation.

Consequently Kate Evans’ portrayal is very intimate and physical: animate and material, supported by the fleshy, inky grownup-cartoon style of her drawings. The danger here is an excessive focus on Luxemburg’s inner life, potentially depoliticizing her, but on the contrary the book conveys a wonderful sense of the wholeness of the revolutionary’s private self, her public ideas and the tumultuous era in which she lived. There is a scene in which Evans quotes directly from The Mass Strike, Luxemburg’s treatise on spontaneity and organisation, juxtaposed against the passionate coupling of Rosa and her one time lover Leo Jogiches. Evans uses this somewhat arch collocation to illustrate Luxemburg’s appreciation of “the limits of theoretical understanding”, one founded in the rootedness of her theory in the material world. The movement is a living thing and, like Rosa and Leo’s own relationship, subject to violent torsions, contradictions and like all life, always developing in unexpected ways.

This idea is suggested in the contrasting, liquid aesthetics of Red Rosa. Initially I found Evans’ style to be cramped, even stifling – crowded panels delineated by empty bands, swamped with thick handwritten speech. Where the figures transcend these frames it is as if they are elbowing for room in these oppressive spaces, emphasizing the limitations of the layout rather than freeing them from it. But as the narrative develops the playfulness of this style becomes apparent, the cramped panel work contrasting with modes that explode out of it – dreamy spacious sequences where the lines disappear, or where they fracture and the frames become angry fragments. There are scenes which toy with info-graphic like techniques where Luxemburg patiently explains her ideas. These aid the readers understanding but also convey the concreteness of Luxemburg’s thought.

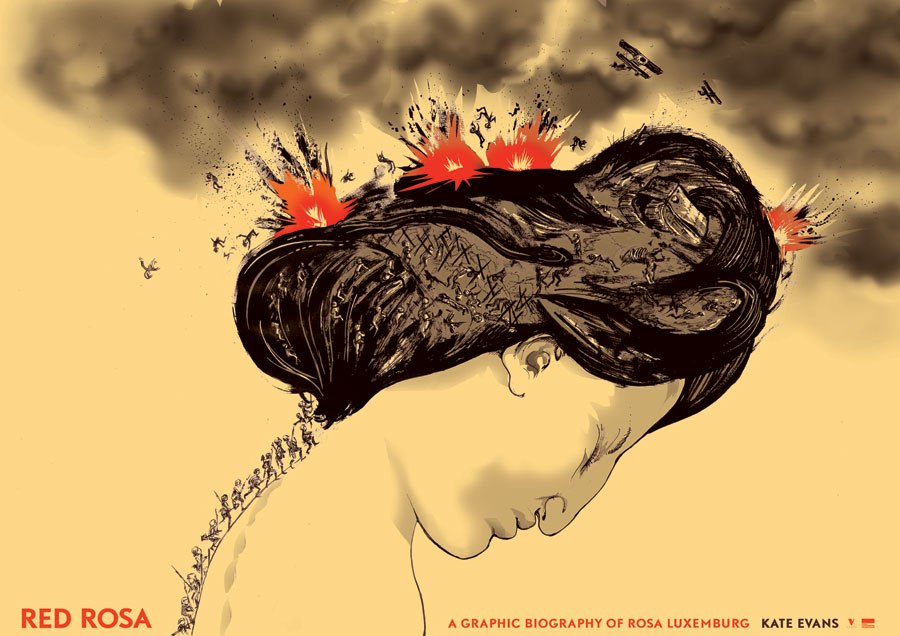

The most powerful idea conveyed through the contrasting aesthetics of the novel is that of the dynamic nature of social life in an era of struggle. The very ‘cramped’ and regulated manner by which we are introduced to Rosa’s world is periodically overthrown by rich artistic convulsions that spill across the page and sometimes between them, symbolic renderings of epic events, war and revolution. These shifts in style feel spontaneous, even ecstatic, and they convey the ingenious, unexpected nature of these moments when the masses are making history and not simply being made by it. This is also mirrored in the comic’s representation of Luxemburg herself. Evans plays the constrained, meticulously constructed early 20th century image of the “decent” middle-class woman, the image of Rosa Luxemburg the left has grown used to, against a wilder freer Rosa; Rosa the lover, Rosa the prisoner, the Rosa of her own imagination – running through the streets in her night gown, her black locks streaming and unbound. Frequently this overturning of the familiar image of Luxemburg coincides with the representation of social upheaval, culminating in the defining image of the book. Embattled forces entangled in the luxuriant cords of Rosa’s hair, the image brings together the novel’s sense of how Rosa’s identity was shaped by the events of her era, just as she was struggling with the question of how to shape them. It’s a lovely detail of the visual language of the novel that Luxemburg’s hair recurs as a symbol of her position as a woman in this period, and her fight for personal and intellectual freedom as well as for human emancipation itself. In Evans’ representation of her, particularly in this image, we can see how these battles are inseparable.

What slightly undermines the effectiveness of these otherwise gorgeous illustrations is the grey murkiness that fills a lot of the negative space in them. I think this is a result of reproduction and Evans appears to have originally created Red Rosa in color. I don’t want to suggest that the aesthetic is defeated by the effect, but something is definitely lost and I hope that a color version will eventually become available. If I was to suggest more meaningful potential criticisms of Red Rosa they would be political differences with elements of Evans’ world view and thus the representation of her subject. The author is extremely scrupulous in not speaking through Luxemburg and, faithful to the revolutionary’s voice, the book is a great introduction not only some of her ideas but a Marxist critique of capitalism more generally. However the relationship between Rosa Luxemburg and the Russian revolution is underexplored, and consequently under appreciated. Just as Stalinists tend to rob Luxemburg of her critical relationship with Lenin, many libertarian socialists retroactively cast her in their own image as a champion of spontaneity in the face of Bolshevik “vanguardism” and terror, an alternative to the Bolshevik project as opposed to a contributor to it. Some of this kind of revisionism is present in the comic.

That said, the absence of Lenin is also a kind of strength of the book. The uniqueness of her contribution has often been lost in the effort to explain how the Spartakists tailed the Bolsheviks, in treating the experience of developing German communism as a cautionary tale about the need for a definitive break with reformism. The virtue of Evans’ fresh eye on the topic is that she hasn’t had to struggle against these tendencies but seems to have simply followed her natural inclination to remain focused on the life of her central character and, particularly in the closing pages, on its significance to future generations of anti-capitalists. Evans’ portrayal of Luxemburg’s death is brutal and powerful but most importantly she resists the temptation to allow it to morbidly define the work. The book goes on, and carries the vitality of Rosa and her ideas with it. Rather than asking whether Luxemburg’s fate could have been avoided, on examining the strategic contingencies of the break with Social Democracy and the balance of social forces in the thwarted revolutionary moment, Evans asks us where Luxemburg’s ideas can take us now. Where does that spirit live? Where is it fighting today? The greatest argument I think I can offer in support of Red Rosa is that it left me with an urgent desire to go out and find it.

* * *

Kate Evans, edited by Paul Buhle, Red Rosa: A Graphic Biography of Rosa Luxemburg. London: Verso Books, 2015. 224pp. $18.95.

Red Wedge is currently raising funds to attend the Historical Materialism conference in London this November. If you like what we do and want to see us grow, to reach greater numbers of people and help rekindle the revolutionary imagination, then please donate today.

This review was first published at the website for revolutionary socialism in the 21st century.

Caliban's Revenge is the dog faced spawn of Prospero and his mistress Sycorax. He draws the cartoon for UK socialist magazine rs21 and works in a South London college where he teaches adult students to resent the English Language and plot its demise.