Matt Woodward’s work addresses the divestment of historical referent from the commodified American monumental structure, and its effect on the collective psyche. In 2014, he spoke with one of Ashley Bohrer’s classes about his exhibit at Comfort Station in Chicago, It Ended With My Putting It On. This conversation is an extension of that one. – The Editors

* * *

Ashley Bohrer: I'm really interested in this claim:

By detaching a history from its naturally given place, space and time in the American experience is bizarrely blurred into a constant present. History, marked ordinarily by a movement of intelligible, sequential events, is recreated simultaneously in space rather than consecutively in time. Distinct, unrelated events appear all at once. The American city becomes a redesigned, revised, corrected simulacrum of the crisis it borrows from, without any of the tremendous, revolutionary pressures that would foreground it. In this way, time is paralyzed; the narrative that makes sense of cultural events is absent, and its message cannot be assimilated. At this intersection indeed the world may be gone.

Especially because it seems like Americans do as much as possible to dissociate themselves from history, especially politically. The history of Native American genocide, of slavery, even of leftist radicalism seems at every turn denied, or better even, repressed. And so, I agree that history is always present, but in the form of a lack, a constitutive lack. America could not be what it is without the disavowal of its traumatic past and therefore, repetitively traumatic present. In that sense, I'm also intrigued by your claim that the simulacrum of crisis, the repetition or copy of it embedded in the cityscape, has been “corrected”. It seems to me like the crisis is ever deepening, ever more grotesque, and the city, no matter how beautiful or ornamental in certain areas is necessarily marred also by urban disinvestment, segregation, poverty and that the crisis itself is the permanent co-implication and co-constitution of these two sides of the city.

Matt Woodward: Yes, okay, there’s a lot you’re saying here that I can agree with, indeed, but in particular it’s that disavowal, as you say, that willingness to stiff-arm an awareness of its own historical shortcomings as if it reproached even its own tail as it’s chewed down. And there, I think, is a pivot point, an impasse that the American city as a node of historical traffic remains impossibly unaware of after all this time. It remains mired in that “constitutive lack.”

And I think this is what so much Pop Art, and Dada, and other art in the 1950s and 60s was trying to do when it plowed directly into the dislocated ethos of its time, when it tried to trigger from a mimetic experience of reality an actual, more tangible one. A reality that, while residual tracings of it were everywhere, had long since been dissolved, and which Pop sought not so much out of a repression but out of an endurance of its tracings.

What Pop was trying to do, and in its cheeky way what it did, was reconcile how mass production had estranged American culture from its context by filling it with referents to the point where, as people living in it, we had begun to see ourselves seeing it, numbly waving across to ourselves in a dream, and Pop tried to reify the distance that had accrued there.

And by inverting that mass production in on itself in order to invest in its prowess, Pop, there unable to reinvent one, instead revealed to us an enormous impasse where it could not coax a revolutionary spirit.

The dissolved aesthetic territory that a lot of this kind of work was attempting to reclaim can be traced back to the early stages of large scale Industrialism, the Golden Age of mechanical reproduction, where there was created a culture and a life of auto-reference, which turned upon itself and manufactured as its content its own cultural production. Again, that snake eating itself.

Ritz-Carlton Study, Mixed-Media on Paper 48’’x84’’ 2014.

What my own work tends to draw from, what it borrows its imagery from, is a hangover of debris left by the City Beautiful Movement, or the Beaux Arts, which still ebb through American cities. What is generally understood about the City Beautiful is that it was a government-funded project that intended to invest its citizens with a sense of sovereignty, and celebrate the country’s newly Empiric stature, and it did this through a glossary of serially reproduced iconography that dated back to a Classical architectural idiom.

Anytime you work in retrospective modes, or plan with retrospective means, however, there will be bizarre, spectral effects later, and that’s especially so when the thing planned is a city. What the engineers behind City Beautiful or the Beaux Arts Movement or Arts and Crafts or any other revivalist movement understood was that behind the ideological muscle of any representational art is its use of signs. Signifiers. The people within Beaux Arts weren’t concerned so much about high taste and high society and beautifying cities; rather, they undertook the task of assimilating and producing and installing an unmistakably classical iconography over a huge amount of space because they understood what the unique results would be.

They had looked inwardly to see its effects, watching how commodity exchange and mass production overwhelmed and controlled a person’s experience with reality. And they saw how architecture belonged to this exchange, and that it, too, could situate a person within the novelty of a particular market – such that events that seemed to take place in a neutral setting, an architectural setting, linked participants to a brand image. Creating a lineage of consumers to a particular economy, an economy that, while it does not remember what it eats, eats only what it buys.

They knew that by recreating these brands, these forms and icons, they’d restore a set of signs whose primacy they enlisted as countenance. An icon, whether an image for religious use or a political symbol, is a sign expressed as a physical, material object that is able to broadcast the qualities, functions, and properties of that sign – in other words, its content. In this case, its venerated content.

And it is that veneration, presented here as a market commodity whose extrinsic value has been replaced with exchange value, that allowed the sign to mediate between its form and its content. This restoration, this recreation, allowed the City Beautiful and Beaux Arts to enclose the space, structure, and program of a city into an overall symbolic setting, which is literally the doorway to a world of myth.

By restoring these icons, they were able to create an entryway to a new, idyllic world – a dream world, yes, fabricated, but a world nonetheless. Whitewashed and imperial. And once it gets there, once it’s reconstructed and fabricated, it may then coincide with the desires of whomever has bought and paid for it.

Untitled (Dublin), Pencil, Paint on Paper, 11'x7’, 2014/15.

However, I don’t think anyone anticipated the bereft and weirdly baroque nightmare that eventually crept across cities like Chicago and New York, places like Buffalo, and Cincinnati--how time, in its transparent folds, was scrubbed of the agony in remembering, existed ambiguously without the distinction of duration and artifice, and, furthermore, without even the prospect of ever actually being able to make contact with a memory written there at all, cultural or personal or otherwise. This is the lap I mentioned earlier, where Pop stood. And so, without an accorded primacy, a feeling of commemoration arose among these structures, a communion in which both subject and object, blocked from communication with their own time (since these objects, and structures were, all in all, not theirs to commemorate with in the first place), seemed either to refuse to mourn, or simply were unaware that they mourned at all.

In this way, Beaux Arts Architecture, by way of a classical idiom, engendered a Capitalist interpretation of history and, as a point of contact between mass production and the built environment, trapped the city in a feedback loop of repeating forms and material lives, stuck pinwheeling in a sorrow without closure.

Capitalism, contrary to really any architectural experience, is not concerned with memory or with nostalgia or with remembering anything at all. Rather, capitalism is out to expand and reconfigure its gains, to exploit and, as you say, disavow. It forgets, and it forgets purposefully in order to expand further, and in its forgetting there is a bleaching forgiveness that is so total and permanent that it is negating in its testimony.

Polk Street, Mixed-Media on Paper on Paper, 101"x96" 2014.

History here affirms Guy Debord’s claim that it would become nothing more than spectacle, something indisputable and inaccessible. Classical architecture has all the regal exploding stature of a monument, and a monument is a device intended to reclaim a territory, to take charge of it. That there is no territory, no event to reclaim or dispute, has only enlarged the mnemonically ambiguous assertion of architecture’s statement.

It is here that capitalism was able to furnish a material link between the architectural surface and processes ordinarily contained in a political context; a link that pushed architecture into a political economy that does little more than distribute signs. It deployed the monolithic and monumental as ideological logos in a political fixture. Signifiers. And, henceforth, it filled the landscape with a plastic bumpercrop of architectural products without depth or autonomy, and incapable of contact with the godly, enormous, and public channel of psychic energy. In turn, the public psyche remains dislocated, unable to heal. Your “constitutive lack” of history. And since architecture is meant to be a conductor of material life, an engineer of material life, it is here, in its overly mass-produced form, that a fundamental contradiction surfaced with uncanny noise.

As this iteration of architecture was serially produced to almost innumerable levels, and became ever more submerged in the political commodity-sign economy, it still remained very much itself – an intrusive structure capable of affecting air and light, of becoming space and atmosphere, of becoming the very world.

And less than an inspiration of a classical spirit, Neoclassical architecture assumed an ironic distance from the fraternity and liberty and sovereignty it meant to represent. Instead, it confirmed that images are only capable of referring to other images; as forms of representation, they are coded with a reference they cannot uncode. Even when attached to venerated iconographic events and things, they are reappropriated objects, hollowed out for a separate purpose, and they belong to another. As such, they are no more capable of entering time again than you are capable of entering a mirror. They are ineligible for becoming real. Their subject is and remains superficial, but even still, artificial or not, they are a corpus of architectural forms, which do what architecture does best: they call attention to modular space. And, in turn, they call attention to our bodies as subjects in that space, in the depths of a reality that we can no longer access.

This is the trauma to which so much of our history, so much of our art today, is beholden. It is what our collective memories cannot capture. It is a rupture in our understanding of our own place in our own time. And confusion about that place is confusion about our place inside and outside of history. And it’s that confusion, repeated impossibly, that designates an obsessive fixation of the body in a midst of irretrievable grief. This is the disavowal you are talking about.

AB: Talk to me a little bit about the affective orientation of your work. Some of it seems to engage with the city in the mode of grief or recognition of trauma; other pieces, with an air of humor -- or at the very least satire -- tearing back the veil of the city in a mode of affirmation rather than pain. Some of your pieces feel imbued with a kind of romanticism or longing, others are shot through with brutality. How do you negotiate, or how do you intend your viewers to negotiate these various, and indeed contradictory, affective orientations in your work?

MW: I have never liked the idea that my work hang on a wall. I want it to leave the wall. I want it to leave the place of vision and enter another experience.

As forms, I want them to do as forms do, surely, but since they are bound by their physical limit, I want them to also reach off and emanate and pound around in space. I want them to find the boundary of things, of context, and interact with the viewer’s space through that boundary .

I try to do that by taking into consideration the structure of the room the work will be hung in, as well as characteristics or objects in that room; where the floor meets the wall, doorways and window frames, benches. Pianos. I want you to bump into these things when you’re trying to look at my work. This is the primary function of sculpture--to reveal by way of material the structure and content and character of space as a practiced place. It’s in this way that I’m trying to take an indexicality usually associated with architecture and make it the property of sculpture.

Moreover, I want that material consideration to stand like an inbuilt eucalyptus windbreak between the artwork that you are looking at and the memory or the association you may have with the stuff that it’s made of. That memory is as unsilencable as an archetype, like I said. It cannot be uncoded, and I love that it stays that way. And so, like collage, my work depends on certain qualities of the material looking familiar, though remaining specifically out of context. This is inherently juxtapositional and part of that fixed, contradictory nature of the work you’re noticing. And it’s precisely right there that I’m trying to stick my viewer.

It Ended With My Putting It On, at The Comfort Station, Chicago. Cutrated by Jess Devereaux.

So, when you ask how I want someone to negotiate my work, indeed I want them to move around with it. I want them to want to touch it and get touched by it, I want them to eat it. I want them to not be able to help themselves and eat the work. I want them to walk with it, all of it, and I want them to notice that within the rhythm and repetition there within each of the drawings and their surfaces is also a differentiation. That differentiation is everything. It’s there that the work’s latent material boundary can begin to effect spatial organizations. This, on a much larger scale, was once the function of architectural ornamentation, only here it is completely decontextualized from that function. And with a scale that is at times rifling and flatly confrontational, I want the work to plot the viewer’s body into a consideration with the room they are standing in, so that they too become as much a position in a room as the walls that lead them through it.

However, as images, again, they remain in that recalling, grieving feedback loop. And I want the viewer to let them be recalled, or as you say, “longed for.” I like that: longed for. I like that the viewer will have to tunnel through time to find a constellation of indeterminate and diverse meanings to link them to. What I find wonderful about working with all kinds of readymade materials or found materials is that there is not any inherent genre to any of it, material can be tilted in any direction. Most of the stuff I use has been so deeply ingrained into ordinary daily life that there isn’t any longer a particular set of traits to grant it, and so it acts ambiguously when you find it here in my work. It’s no longer itself. Glue. Spackle. Blinds. Coffee. Even paper. These are household things, commonplace, always at arm’s reach. But as lordly, complex, and wild as anything else.

And so, yes, it’s in that material where your longing occurs. Where it wardens in and there’s a yearning, a loss, an absence of context, of function, a strain where the repetition of the forms as a reckoning seems to rush toward the viewer like a handful of sand. There, where the material comes in contact with the image, is an encounter with the world. The real world. Or almost an encounter. What Barthes calls a “floating flash” of it.

Here, the material itself, which is still recognizable and has tangible, physical touchable smellable qualities, is ripped and dripping and bodily and musically hasty as a surface agent. It is impossible to not want to recover and illuminate its whereabouts. And it is here that the image advances off that surface through a moment of alterity. It is here they compete to create a kind of confluence, a screen, a hallucinatory certainty that abuts against our catalogue of tiny knowledges. And it’s in those rips and ruptures and gouges, and in the repetition, which the image itself seems tasked to resolve, that the real comes drifting up to the screen. But instead of clicking into place, it slips away, withdraws in a floating flash.

Polk Street detail.

Judy Pfaff is an artist I go back to regularly who I think discusses this kind of point beautifully. Her work steps from sculpture to what looks at times like commercial window display cases in a way that connects a mess of dislocated cultural iconography with a material diagram. By diagram here, I mean an organization of forms that describes relationships, and which, in turn, elicits a particular behavior in space. That behavior somewhere conceals consumer and viewer from each other.

Within her works there is a dense web of dislocated signifiers, and it’s from those that she’s able to evolve further a rather Rauschenberg/Richter-top-heavy discussion about painting in a message-saturated time.

It is not possible to stand in a room with her work and not feel blitzed in a cone of raw register, not feel those signals snagging and snarling at something in you. Around you. It’s overwhelming. The entire makeup of her works--plastic flowers, maybe a bed of netted birds, a lost-n-found red scarf, winter fungus, etc. – all of it comes together to create an ambiguously defined environmental boundary, an arrangement of material so intense that it almost dematerializes the perceived glossary of its disparate parts into a single structural whole, a monolith.

Almost. But it doesn’t. It doesn’t dematerialize, it stays together as a series of swarming parts and, through an elaborate and tactile design organization, Pfaff is able to use her materials to seemingly impart a rejection of its own tectonics. Therein unfolds a discussion in which part-to-whole relationships together imply a performance that expresses the dense component-specificity of her work’s content.

It is here that the screen I’m talking about appears and refrains: in her work’s refusal to diffuse its own edges and boundaries and borders in order to benefit a superconductor of deployed signifiers. Here the work goes further than its surface fixity and slips past its own framework while staying locked firmly in step with its own aesthetic imperative.

This discussion for me is an architectural discussion, as architecture is, again, a quality, a value taken from out of material organization.

AB: I'm also really interested to hear you articulate why the city, why architecture. Of all of the traumas, trials, and tribulations, of all the testaments to the struggles of living in common, why does the architectural in particular captivate you? What is unique about architectural scapes, spaces, and ornamentation, why the outsides of buildings rather than that which lies within them, why sculptural ornaments rather than lighted marquees (etc. etc.)?

MW: Yes, I am interested in architecture, surely, but more so I am interested in drawing as a medium that, if it’s good for anything, is good for its ability to express forms in relationship to their surroundings. I’ve found the two, architecture and drawing, to be interesting bedfellows. Like architecture, drawing is not merely reducible to its media in the same way architecture is not merely reducible to buildings. When I say something is architectural I’m talking about the physical receipt of material agency, the engineering of a material life made manifest by the built environment.

And, to get back to what I was saying earlier, a primary effect of power linked to architecture is its ability to organize that environment, that space, into a juxtaposition of functions. One of those very human functions is that it helps contain and make accessible a cultural memory. This cannot be overstated.

This is the battle I’ve chosen for myself. The remaining relics and products from which my work draws is the still-charged, left-over circuitry of architectural function, into which once we could put meaning and then take it back out, and then, in turn, replace it with other meaning. This has had almost irresolvable and disorienting effects on the accessibility of cultural memory.

I am part of a generation that has often been criticized for its inability to make comprehensive statements, for being singularly obsessed by a self-serving interest in material knowledge and, ultimately, for making emphatically unsturdy statements in sturdy mediums. And I’m not exactly interested in making some kind of a neat, over-arching comment to excuse anyone from that criticism. Having said that, I do think what my peers and my generation seem most fixated on – and capable of achieving – is the reconquering of space and time and the memory that flows inside them through a network of material processes; a re-territorializing, a repurposing of the Now by way of the political and social inroads contained in and revealed by those processes. And as lofty and majestic as it seems, to let the Now live again inside of us by reinstating the very mass-produced and artificial narrative that had sublated it to begin with, so that the Now, in turn, can live again and give recourse to our imaginations. We are not reinventing the wheel, we are helping to break into the wheel.

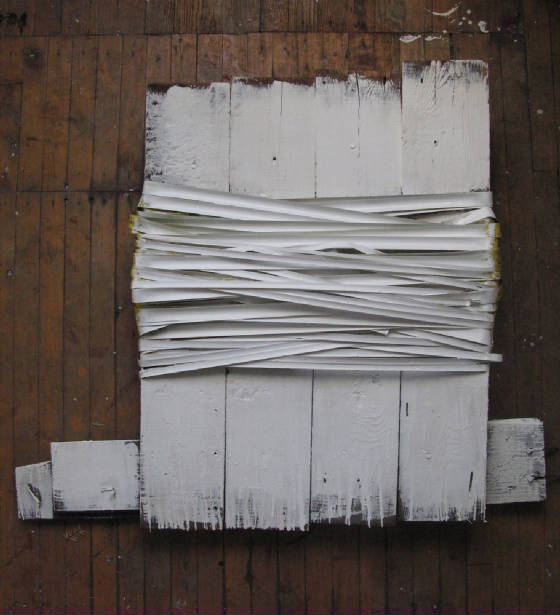

Hardware Store and Back, Measuring Tape, Paint, Wood 33x4x39 2014.

What my generation understands is that historical context, which is inseparable from the meaning of the artwork, is a material performance that is not necessarily physical, and can be used to construct, rather than reproduce, the real. That, if we approach material as a source latent with ideas and effects, a supplier of them, then we can begin to tap it for the dynamic transcultural signifiers that are already built into it. And that disclosed within these material processes we are allegedly obsessed and distracted by is a network of effects crucial to updating space, to recontextualizing the high entity of meaning that’s disappeared from our cultural narrative.

This is, at least, what I’m trying to do with my own work, and probably the only thing it’s capable of providing. By reclaiming these things as monuments, they are restored as objects, and may then participate in the occasion of their historical entry point with a reality that they never before possessed. If all we see asleep is sleep and all we see awake is death, then let my work commemorate the grief in not ever having either, sleep or death, and the peace in never knowing it had lost them.

That inside/outside situation you bring up is something I was attempting to discuss with Park Monument (below). Through some dumb luck in the studio I discovered that Painters Tarp, a cheap, whitely opaque surface you can get at the hardware store, turns transparent if you hit it with glue. I got a bunch of them, tiled them all together and used them to make giant photocopy-transfers of another drawing I had made and then I wrapped them around both real and artificial Christmas wreaths. I hung these wreaths in the windows at the Comfort Station. The drawing I used as a photocopy, of course, is a drawing of a different wreath, one I found on a monument in Washington D.C, and it was kept out of the show.

Park Monument, Width Variable x 4' Mixed-Media on Tarp, Synthetic and Actual Wreath, 2014, pictured in situ at the Comfort Station.

The photocopied image, however, would not show through the tarp unless it was illuminated from behind. And so, whereas the conventional architectural detail articulates stress and pressure occurring within a building’s internal structure, here that relationship is reversed and the detail – the drawing – is illuminated essentially by stress coming into the the building, the gallery space, from the outside. In this case that stress is sunlight. Without that sunlight, the image is, again, essentially inactive, and you can’t tell what it’s doing. It doesn’t work, it just hangs hidden in the tarp surface, there wrapped around the wreath.

And so the tarp allows for a kind of structural casing, an envelope that operates as both a surface attachment as well as a point of contact for the inside/outside opposition that the detail itself is ordinarily a material reflection of.

Through the Painters Tarp I was trying to play with architectural rules, of which the detail, naturally, is an extension, and, moreover, as an image, a loyal messenger. I was also trying to reveal the surface’s capacity to both reorient relationships and become a kind of product in doing so; to let the tarp become skin, or some textile virtue, which pressures both architecture and product to generate effects rather than simulate them. By forcing the detail into this merit, the envelope is able to sidestep responsibilities usually associated with construction, and instead take up issues wherein differentiation, distortion, transparency, the surface, the artificial, the monumental, even the work’s floating and hanging aspects are granted affects loaded with political and social potentials.

State Street Study, Mixed-Media on Tarp 10'x10' 2016.

And I think this has something to do with why sculptural ornament and not lighted marquees, what you were asking about earlier, why architecture and not something else. I’ll spend my whole life trying to answer this. When I was a kid, about eight or nine, I used to leave my house in the middle of the night in the winter and go out for a walk. I’m from outside of Rochester, and there isn’t much out there but field and farm and woods. So you don’t have to go very far until you’re alone and well inside of either. And in the winter, in all that snow, in the night, these fields are middleless. I used to go into them for hours and lie down and feel the low dulcimer whir of the quiet in all that black and landglow. It would just hum and open off there. And when I’d go back home I could feel my body like a new variable, separated away from the facey houses, which had been jammed in the singing daylight but now were only law. Inventory. Law. I could feel them dip against me and I could not enter them. You could crack them off the world it was so dark. The world cost nothing then, you could carry it through a keyhole. I remember standing in front of them, and they’d chuck toward and flatten, they’d advance and distend and climb back to their huge faces, and they’d frame me in the world like a kink in a palm, the way a near deer will frame you from the very ambient heights of its glimpse and you can feel the air in the world harden around you before it gets away. A foil around the night that slides against its turn. There, in the road, you can feel your body in the flipping sense of every object, every space a lip of moon and tree. An edge of real air.

I know that there are much more direct routes to facilitating change, especially now, when art-making has become as much a luxury activity as it is a right encroached upon and worth dying for. However, and this is what’s most important, the radical means through which art-making does effect change indeed made its way to my life once, and I wanted to be better for it, as a man, as a citizen, as a thinking individual, it changed me. And so it is my hope that through my own work I’m able to confront the same kind of person, the kind of person who cannot help but be changed in the right way.

Red Wedge is currently raising funds to attend the Historical Materialism conference in London this November. If you like what we do and want to see us grow, to reach greater numbers of people and help rekindle the revolutionary imagination, then please donate today.

Matt Woodward was educated at the School of the Art institute of Chicago (BFA 05) and the New York Academy of Art (MFA 07). He is previously an instructor of Art at Dominican University and has lectured at schools and colleges throughout the United States. Woodward has been an artist in residence at the Edward Albee Foundation, Cill Rialiag in Ireland, the Vermont Studio Center, MICA’s Alfred and Trafford Klots International Program in Lehon, France, as well as others. He has appeared in numerous publications including New American Paintings, and has been reviewed in places such as Art Pulse, Chicago Art Magazine, Bad at Sports and Art Critical. Currently, Woodward lives and works in New York. He is represented at Linda Warren Projects, where a solo exhibition is scheduled for 2017.

Ashley Bohrer is an academic and activist based in Chicago. She is a member of the HYSTERIA editorial collective, and has published at Truthout and Al Jazeera America.