Paris based cultural theorist Boris Groys exerts a strange pull on the minds of many who seem predisposed to accept what he has written about everything except the Soviet experience. When it comes to his writings about the relationship between art, curation and the internet, he is listened to and his ideas are formative of our contemporary discourse on modern art.

When it comes to his varied works on philosophers, we engage with his iconoclasm. There is something attractive about a way of looking at philosophy that draws its model from Duchamp’s (or R. Mutt’s) expo of an upside-down urinal.

But whenever his writing turns in the direction of the Soviet Union – whether it is about Suprematist painting, Stalin’s essay on language, or oppression in the Soviet era – we cannot listen any more easily than when attending to Heidegger’s most notorious statements from 1933.

Just as Heideggerians have striven hermeneutically to recover the philosopher’s authentic Being beneath the Nazi décor, so it is tempting, when faced with work like Groys, to do the same. Yet what is highly disingenuous in the former is doubly suspect in the latter. While Heidegger chose to conform to the regime, and by his post-war silence, maintain that conformity along with all those ex-Nazis who kept their jobs, Groys is openly being contrarian. We cannot excuse him on the grounds of saving his skin, or opting for the comfortable life.

This leaves us with a choice. We can simply ignore The Total Art of Stalinism and The Communist Postscript, or we can put them centre stage and show how they form the ideological core to the ‘good bits’. If I may use an analogy, not a million miles from our subject matter, the situation risks the kind of procedure we experience when watching Eisenstein’s October. While undeniably one of the greatest cinematic experiences to be had, there is an advantage to watching the film at home. We can fast forward over the sexist portrayal of the Death Battalion, and the scene where Trotsky speaks against the seizure of power, while securing an unfettered enjoyment of the equally false presentation of the storming of the Winter Palace.

According to psychoanalytic theory, the act of splitting occurs when we avoid something in ourselves that we cannot face. By projecting onto someone else, we can then hate wholeheartedly, in order, better, to have unfettered possession the self to whom we aspire.

The problem, as any analyst would point out, is that the good part becomes neurotically good, while the bad part keeps returning when we least expect it. In the case of Groys, if we refuse to attend to his Stalinism we risk it creeping back into those spaces of discourse form which we thought it banished. For this reason, we have to proceed methodicaly – to begin with the parts of his work that we find least objectionable before proceeding to a close reading of the truly objectionable, and before developing an alternative method to look at the same material.

Saint Boris: The Curator

Groys has made his name in the realm of art and curation. The relationship between artwork and gallery forms a structural nexus that helps us to understand what takes place when his writing turns to high theory and politics. In simple outline, by the early 20th century the avant-garde sought to attack the gallery and reduce the gap between dedicated spaces that contain artworks and the rest of the world. In short, they sought to reconstitute the whole world, via the act of radical art.

In the 1920s this became possible in the Soviet Union as the state gave artists a role beyond anything that was possible elsewhere. Groys focuses on avant-garde painters like Malevich, but it could be argued that it was in music that this was tested to the limit. In 1922 to mark the fifth anniversary of the October Revolution, Arseni Avraamov performed his Symphony for Sirens, lasting seven hours in the streets of Baku. By standing on top of a building with two red flags he conducted an orchestra consisting of church bells, factory sirens, the foghorns of the entire fleet of the Caspian Sea, guns, trucks, a choir and a whistlemachine he had specifically constructed to performing the Internationale. In this performance we can see what it means for art to dominate space and reconstitute it. In this case the artist had taken control over the city and turned it into an orchestra.

This relationship between art and world is explored via the development of installation art. Here the artwork aims to take over the gallery, but rather than abolishing the gallery it extends the power to the curator. Galleries are turned into spaces where curated events take place, and artworks are moved around the world, continuously being rearranged to fit in with the curational system.

Boris Groys.

In Into the Flow, Groys extends this process to the internet. In a way, this is the telos of the process that firstly began with the avant-garde questioning the gallery before becoming absorbed into a refunctioned conception of the gallery under the control of the curator. But now we are all curators. We use the internet to amass and arrange images, turning our screens into exhibition spaces, and bringing down the barrier between art and world by staging micro exhibitions in our homes, our workplaces and anywhere a mobile device can pick up a signal.

In a sense Groys’ depiction of this process gives us a clue to his own method as a writer. His most methodological work is Introduction to Antiphilosophy. Through a collection of essays, he traces a process by which philosophers gave up on producing self-contained systems rooted purely in thought, and sought to seize hold of what they found lying about in the material world. As with Duchamp, they displayed these ready-made objects. Marx displayed the labour process under capitalism, Kierkegaard displayed the ethical lives of the provincial bourgeoisie.

When we turn to Groys, he is doing the same thing. Building installations that aim not to mirror reality as in the traditional notion of the mimetic artwork, but to take it over and display it. We see this in his account of the communist experience, where he does not write an historical account, but assembles an argument about what communism should be, is and was. He curates political and aesthetic material, and like any curator, threatens to occlude other equally, or more valid, curational options as we shall see in the conclusion.

From saint to sinner: The Platonist

The curator is a kind of Platonic guardian, or philosopher king. They do not seek to produce individual works that in their internal integration of form and content hold a mirror to a world beyond. Rather they take over that world, and do so as a whole.

It is perhaps best to begin by understanding Groys as a constitutional philosopher, and this takes us through a digression via German Idealism before we can tackle what Groys has to say about Plato and communism. This goes back to the debates among post-Kantian philosophers around the year 1800, principally Fichte, Schelling and Hegel. In many ways these debates form the template for discussions about how we go about theorising the relationship between subjectivity and changing the world. Like Fichte, Groys thinks in terms of absolute starting points and inaugural moments that constitute (the German is Gesetze) a whole process. Fichte developed his theory of the Transcendental Ego, as an absolute point of origin, who through an act constitutes the world of the non-ego, via a Tathandlung, or action. As opposed to Descartes the origins of any philosophical system lay not in the contemplation of an external reality, but in its production by a consciousness that imposes itself – hence the usual accusations of idealism constituting material reality. Goethe’s Faust satirises Fichtian philosophy, by having Faust re-write the Bible to read – in Anfang war die Tat! (in the beginning there was the deed!).

Schelling was the first to object on philosophical grounds, by developing the theory that nature is an unconscious productive force that must shape the Transcendental Ego – resulting in the world as a unity of unconscious and conscious production. While we should revisit Schelling as a subterranean influence on Marx and Freud, a part of his neglect lies in the fact that Schelling never developed a stable methodology for showing how the unconscious productive and the conscious productivity of the Transcendental Ego (subject) are mediated. In this sense the more established opposition to philosophical constitutionalism can be found in the Hegelian procedure by which there is no absolute starting point, but rather a process that internally mediated. If we recall the opening to Hegel’s Logic, the inaugural discussion of being shows that any a notion of being is already mediated by the categories of nothingness and becoming – that ‘being’ can never be absolute, but determinate. As we shall see, debating with Groys requires a return to this earlier Methodenstreit.

The discussion of Plato is important as it grounds his treatment of art and communism. For Groys, Plato’s Socratic dialogues seize an existing field of discourse that was dominated by the Sophists. According to Groys’ prevailing narrative, Sophists were paid to produce texts and speeches that justified a particular position – usually that of the patron. They were relativistic, in that the same Sophist could write pieces that were mutually contradictory, but were supported by a smooth rhetorical surface and an underlying logical argument that was self-evident - if seen in its own terms.

Plato’s use of Socratic questioning foregrounded the paradoxes inherent in all linguistically constituted writings and speeches. That, while a speech on its own terms appeared consistent, when set against the whole of speech and every speech it was not, and this created paradox – speech that is both consistent and inconsistent.

The only force holding this system of discourse was non-discursive, namely money. Groys sees here an intersection between two ontologically opposed systems – the political and the economic system. The latter is ruled by numbers and the former through language. This forms the basis of his discussion of communism. The latter is the absolute domination of politics over economics and capitalism the reverse.

Under capitalism the only form of success and failure lies in numbers – sales and profits. If we think of the Platonic triad of the Good, the True and the Beautiful, there is nothing inherently good, true or beautiful we can infer from a successful piece of music in a capitalist setting. Debates about the worth of art are infinite, in the bad kind of way, because capital has no process for determining how we judge qualitative worth (use value) over numeric worth (exchange value). All that happens is that works, along with their critiques, proliferate in an infinite market, where all are in circulation allowing money to determine the field through permanent compromise and co-existence.

The only way out of the problem is for the philosopher to seize the state, abolish the market and determine what we mean by the True, the Good and the Beautiful purely by means of linguistic fiat (dictat).

For Groys there is no accidental link between communist revolution and works such as the Symphony of Sirens. Communism in Groys’ view seeks to abolish the gap between acts of language that are separated by the market. Language is an entire field of praxis that determines its own limits. It is synonymous with political power.

When Shostakovich withdrew his 4th Symphony at the rehearsal stage, and retreated from his experiments with dissonance and atonality, it was not for fear of box office failure, but because an article in Pravda effectively decreed that this was not the kind of good art expected of a Soviet citizen. Here the philosopher king in the shape of Stalin could decree the Good, the True and the Beautiful.

Devil worshipper: The Communist Postscript

The Communist Project is a short and programmatic work that was designed to act as a pendant (or coda) to The Communist Manifesto. Its political message was essentially that communism has only ever been achieved once – in Russia from the period of Stalin’s consolidation of power to 1991. Unlike in Eastern Europe where communism was never genuine (he signally fails to explain this difference), the Soviet Union did not fail economically, it decided to dissolve. His account is mythological, it tells a simple story, compelling in terms of its self-evidence, if we fail to look beyond the way he has curated 70 years of Russian history. Like Cthulhu, communism is chained up on the edges of our world waiting to be reactivated by the power of language. As in the case of the Necronomicon, we can see Groys’ book as a diabolical work, aimed at conjuring something from the catacombs of the Kremlin.

The opening passage of the preface introduces the way he thinks in absolutes:

The subject of this book is communism. How one speaks about communism depends on what one takes communism to mean. In what follows, I will understand communism to be the project of subordinating the economy to politics in order to allow politics to act freely and sovereignly. The economy functions in the medium of money. It operates with numbers. Politics functions in the medium of language. It operates with words – with arguments, programmes and petitions, but also with commands, prohibitions, resolutions and decrees. The communist revolution is the transcription of society from the medium of money to the medium of language. It is the linguistic turn at the level of praxis… So long as humans live under the conditions of the capitalist economy they remain fundamentally mute because their fate does not speak to them. (The Communist Postscript, XV-XVI)

If that sounds fairly high-level and abstract, perhaps this passage will help the reader understand the politics that this kind of thinking is serving:

If the question is posed… whether the regime of the former Soviet Union should be regarded as communist… in the light of the definition given above, the answer is yes. The Soviet Union went further towards realizing the communist project historically than any other preceding society. During the 1930s every kind of private property was completely abolished. The political leadership thus gained the possibility of taking decisions, that were independent of particular economic interests. But it was not that these particular interests had been suppressed; they simply no longer existed. Every citizen of the Soviet Union works as an employee of the Soviet state, lived in housing that belongs to the state, shopped in state stores and travelled through the state’s territory… In the Soviet Union, a fundamental identity between private and public interest thus prevailed. The single external constrain was military. (2009, XVII-XVIII)

As all accounts that defend the Soviet system post-1928, this one has to occlude not only the famines, purges and the gulag, but also the primitive accumulation of capital and the forcible creation of a society based on wage-labour. There is not the faintest discussion of how a surplus was produced, who got to distribute that surplus and to what end – which is the ABC of Marxist discussions of class. But, as we should have seen by now, Groys is not a Marxist, and takes his philosophy from Platonic, existential and phenomenological waters.

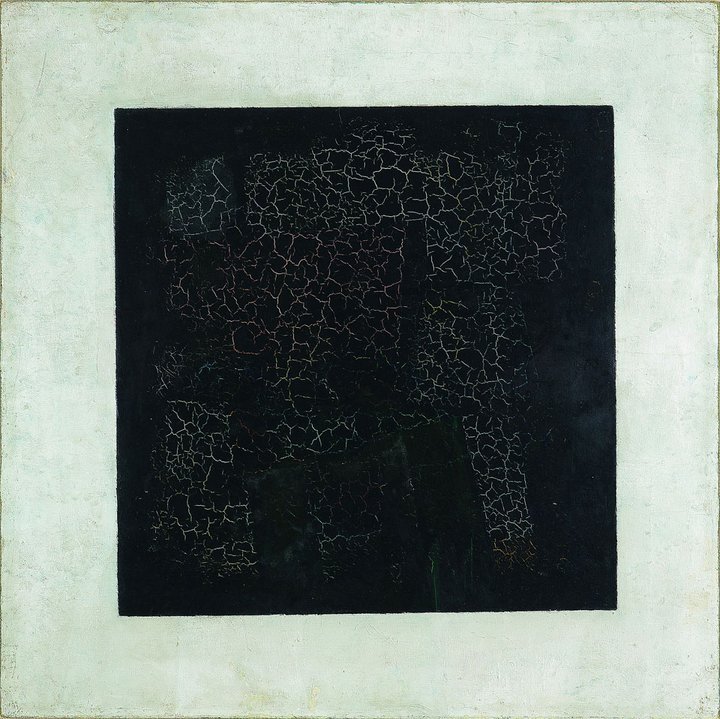

While the ostensible subject is communism, it becomes clear that this is very much a book about philosophy: ‘Soviet power must be interpreted primarily as an attempt to realize the dream of philosophy since its Platonic foundation, that of the establishment of the kingdom of philosophy.’ (2009, 29). The first chapter develops this theme, using many of the arguments we have found already. The foundations of communism are laid in the suspicion that behind these mutually contradictory works circulating there is a hidden capitalist order controlling it all. This forms a kind of power that seeks to go beyond the individual works in circulation to abolish the process itself – to constitute a new ground zero – Malevich’s The Black Square, the communist revolution.

Malevich's The Black Square.

While chapter one produces his most sustained theorisation of language, the second chapter focuses on the paradox. If we recall, it is impossible to abolish paradox, just the circulation of mutually contradictory, but internally consistent discourses. For Groys the theory of Marxism-Leninism is nothing less than the rule of paradox, and the foundation of society on a dialectical process inherited from Hegel (2009, 33-4). Here the transformation of the dialectic lies in the fact that for Hegel paradox belonged the past and could be sublated in the state. Groys sees Kierkegaard as a better foundation than Hegel. The latter pointed to Jesus and showed there is nothing inherently godlike about this figure, and no reason why Jesus and not any other mendicant preacher was destined to be the founding figure of a world religion. There is no internally consistent reason for Jesus, just that the Church had the power to make it so. ‘Paradox should not merely provide the basis for ruling; it should also exercise rule.’ (2009, 35). This means administering the paradox, and characterising any discourse that attempted to resolve the paradox is ‘one-sided’ and to be declared heretical (2009, 36).

At a later point in the text Groys extends this treatment to the fundamental propositions of historical materialism. The base and superstructure are paradoxical, ideas can grip the masses and become a material force, while at the same time being mere reflections of what is going on outside them. These are not to be mediated but juxtaposed, made permanently paradoxical (2009, 52-5). Stalin’s late writings on language are the culmination of this process – language is neither base nor superstructure, but both by connecting directly to all human and material practices; it can dominate the economy directly, by forcing paradoxes together (2009, 55-63).

Although Heidegger is not mentioned, Groys makes a Heideggerian move by arguing that in Dialectical Materialism the key phrase is ‘being determines consciousness’, and there is nothing ‘material’ or any mention of ‘matter’ in this phrase. Being is language and the power it confers when administered totally after the abolition of the market.

He extends this argument from philosophy to political practice – citing the debates in 1908 about whether Bolsheviks should participate in the Tsarist parliament, the Duma. ‘One-sided’ arguments were furnished for and against, but Lenin argued for both. ‘The advantage of formulating a political programme as a paradox here becomes clear: the totality of the political field is brought into view, and one is able to act not through exclusion but through inclusion.’ (2009, 38)

He uses this to legitimate a very Stalinist reading of the debates between Trotsky (on industrial led development) and Bukharin (on agricultural led development). Trotsky and Bukharin could only produce left and right deviations, which were internally consistent but mutually contradictory. Only Stalin ‘liquidated’ these deviations by adding them together, Trotsky plus Bukharin equals the general line. He argues that the conflicting positions were simply placed side by side in Stalin’s formulations (2009, 39).

At this point the reader will have had their fill and realise we are being given the same old song that Andrei Vyshinsky sang as Stalin’s state prosecutor during the show trials.

The ultimate reduction

Historically… art that is universally regarded as good has frequently served to embellish and glorify power (2011, 7).

No book demonstrates an example of an argument that is consistent on its own terms, but in utter contradiction to everything else that can be said on the subject. In this sense, what Groys writes about communism meets his own definition of Sophism, and he is bewitched by the power of his own logic. By adopting the role of curator of communism, he has offered us an expo that presents the totality of Soviet history as the realization of philosophy and the exercise of power as paradox.

The problem with curation is that it is always dependent on the works being produced. Each concrete material work of art in some sense precedes the curational act. Curation is not creation ex-nihilo, the constitution of the world by the Transcendental Ego, or the decree of the Party. It is an act of mediation that requires a material universe made up of intersecting acts of praxis – artists struggling with the materials of paint, wood and stone, moving through and against forms, without knowing where the process will lead. When such artists enter into a period of social and political revolution, they, like the workers and the party, are thrown into an evolving situation. This is socialism from below, rather than the foundation of the philosopher king.

This is a clash not only of politics, but of methodologies, that cuts across philosophical, aesthetic and political forms of activity. If we are to demonstrate the authoritarian and utterly anti-Marxist method used by Groys, we should revisit an artwork that has become canonical for him: Malevich’s Suprematist painting The Black Square (1917).

Groys opens his book The Total Art of Stalinism by asserting: ‘The Communist Party leadership – was transformed into a kind of artist whose material was the entire world and whose goal was to “overcome the resistance” of the material make it pliant, malleable, capable of assuming any desired form.’ (2011,3). He equally asserts that this ‘will to power’ was equally evident in the 1920s avant-garde (who were more interested in transforming than representing the world (2011,14), and that there is a strict identity (again in the philosophical sense of two things which are essentially one) between the will to power, and the artistic practice of imposing form on material (2011, 7). Most controversially the book asserts that the art of Socialist Realism, like communism as outlined in The Communist Postscript, realized this identity of art and power, thus consummating rather than abolishing the avant-garde. That Socialist Realism built on the foundation of the avant-garde (fulfilling its internal logic, (2011, 9), just as Stalinism fulfilled the revolutionary is at the core of a contention that needs to be exposed methodologically.

In chapter 1 he develops the analysis of the avant-garde and its ‘leap over progress.’ The argument begins with a general state on the avant-garde arising at a point in the 19th century when technological progress has set off the process Nietzsche described as the death of god. The unity of a god given cosmos, which art has mimetically reflected, was being replaced by a fragile world in motion, whose outer rim is ‘a black chaos.’ (2011, 14).

It is in this context that Groys focuses the programmatic writings of Kasimir Malevich, before 1917 and after. In a tone that has definite echoes with Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History, Malevich warns that all nature and creative activity is set against progress. That the artist’s role is not to be in the vanguard of progress, which is lurching into a void, and not to find a secure rampart against progress in the manner of reactionary art. Rather: ‘In order to find something irreducible, extraspatial, extratemporal, and extrahistorical to hold on to, the process of destruction and reduction must be taken to the very end.’ (2011, 15)

Malevich’s painting The Black Square was the result of this extreme act of reduction.

The Black Square…is a transcendental painting - the result of the pictorial reduction of all possible concrete content…It presupposes a transcendental rather than empirical subject. The object of this contemplation is to Malevich nothing (that nothing towards which he felt all progress was moving), which coincided with the primordial substance of the universe, or… in the pure potentiality of all possible existence that revealed itself beyond any given form. (2011, 16)

It is worth pausing for a moment before continuing with Groys’ argument. The use of transcendental versus empirical is not an innocent gesture, but reprises the very philosophical constitutionalism we encountered earlier. Fichte’s Transcendental Ego is being transplanted into Malevich’s painting. This same figure is at work in his analysis of communism, and the possibility of stepping outside – transcendence – and adopting a standpoint from which a totality can be constituted.

Groys develops an argument which has echoes with his analysis of communism. This is that technological revolutions had the same disruptive impact that the rise of capitalism had on language. That the geometrical forms of a Suprematist painting were in unconscious harmony with nature, which has been lost (repressed) by technological progress. This leaves the role of the Suprematist painter as artist-analyst to reimpose harmony – consciously. While appearing psychoanalytical, this plays more to the Stalinism of willing or imposing form on a chaotic matter.

The passages Groys quotes from Malevich’s writings lend credence to this kind of transcendental/constitutional reading. Groys also makes a convincing case by situating Malevich’s praxis methodologically alongside Husserl’s phenomenology and its reduction to pure intentionality, or the Logical Positivism of the Vienna School that sought a minimal starting point for truth.

Groys writes of Malevich’s: ‘insistence that harmonizing “materials” and pure color sensations must be made “visible” as if perceived from a different, apocalyptic, otherworldly, posthistorical perspective.’ (2011, 9). He does not use the word Messianic, though the reader versed in Marxist aesthetics cannot fail to pick up on themes from Walter Benjamin. There is indeed something similar between the floating geometry of a Suprematist painting and Paul Klee’s angel. But the angel has eyes that stare into you. Malevich’s black square is eyeless – a black uniform surface of colour that cannot stare into you – it blocks the flash of recognition

Breaking the spell – the revolutionary process

The problem with the analysis, as Groys admits, is that he has focused ‘more attention on the artists’ self-interpretation than on their relatively well-known works’ (2011,14). By boldly stating that the avant-garde sought to transform, not represent the world, Groys imposes a transcendental approach, which overlooks the process of revolution itself.

The Black Square is one-sidedly presented by Groys as an absolute reduction, a constitutive or inaugural moment. If we take Malevich at his word, we can see why Groys says this. Yet by attending to Malevich’s paintings, and by focusing on the relation between form and content, we get to a completely different conceptualisation – one that concentrates on the revolutionary process.

Malevich could not make a leap out of the representational or mimetic tradition, but rather was trained as a technically accomplished realist painter (ironically, we can see this in self-portraits from 1908 and later in 1933). Each of his works in the decade prior to Suprematism (pre-1915) can be seen to be pushing at the boundary of existing avant-garde forms. It is a process we can cite in other domains where Modernism is truly revolutionary – in Schönberg’s transformation of tonality, or Joyce’s transformation of literary realism.

Malevich’s painting Trees (1904-5) takes a naturalist subject matter and is far from the non-objective art we associate with his Suprematist works. Yet if we attend to the arrangement of the piece we see that the painting is foreshortened, almost two-dimensional. The work is made up of four trees, a starkly presented foreground in the shape of a wedge sloping diagonally across the bottom half of the canvas, and a similarly wedge-shaped sky sloping in a diagonal alignment across the top – all colour reduced to a few tones. The arrangement is structurally close to pieces like Suprematism No.38, where the same features of foreshortening, and diagonally arranged blocks with a limited colour scheme are dominant. An argument can be made here along the lines Malevich himself would have made, of nature once being in harmony with Suprematist form, but having lost it at a conscious level, we have to regain it by forcing the original form to the level of consciousness via non-objective art.

The problem is that this is the perspective of the Suprematist painter on the eve of 1917. Before reaching Suprematism, Malevich went though, and exhausted, every available emerging form of painting: Symbolism (Assumption of a Saint, The Shroud of Christ 1908), Fauvism (Self-Portrait, 1908-10) and Cubism (An Englishman in Moscow, 1914). It is only in his costume designs for the Futurist opera, Victory Over the Sun (1913) that we see the transition between Cubism and Suprematism. Ironically it is only when it comes to applying Cubist design to the human body that we get the breakout into separated shapes with firm outlines and colours. It is on the bodies of the players that the non-objective objects of his 1915 canvases comes into existence.

Malevich's costumes for Victory Over the Sun.

Through this process we can see how each painting was mediated by transformations taking place in the previous work. While it is possible to suggest this is a search for the transcendental starting point, and against progress, there is something taking place at the level of material praxis (painting) which is pushing him on from one work to the next, sublating each form dialectically, so that we are witness to a revolutionary process, rather than a single revolutionary act.

The Black Square was a culmination. Much as the Bolshevik seizure of power was a culmination predicated on a series of steps, not the least the political process that resulted in a Bolshevik majority in the Soviets. As Marx said, we see the anatomy of the ape within the anatomy of the human being. To echo another choice methodological phrase by Marx, we could regard The Black Square as a concentration of many determinations. Dialectically it is only possible by the inclusion of all previous forms available to the artist.

To be revolutionary the artist does not have to profess a particular ideology, or abolish all time, all matter, or even to seize the whole and impose some utterly new form. Rather the revolutionary artist has to be located within a tradition, and be able actively to transform that tradition through a process that mediates not only the handed down forms, but develops his or her own form, without knowing what the end result of the process will be.

Methodologically this approach speaks not only to artistic practice, but also to a better understanding of revolution. Revolution as a process taking place experimentally from below.

In October, the Bolsheviks had no conception of Soviet power beyond the contingencies of the moment. Revolution was a chance opportunity that was based more on Trotsky’s theory of uneven and combined development, than Groys’ metaphysics of language and the paradox. The revolution was supposed to take place in Germany, but Russia was the weakest link; through a combination of a weak authoritarian state, a gelatinous civil society, and one of the most organised industrial working classes on the planet, due to its structural interconnection with global commodity production – a strange conjunction arose; a truly modernist experience, in which all previous forms of revolution were telescoped and compressed, giving us a bourgeois revolution in February and the world’s first workers’ revolution in October.

As with the experimental avant-garde, we should not pay too much attention to the manifestos – or resolutions or decrees, but rather to the interface between these and the material practices that sustained the process. In the artistic case this requires a close attention to the formal process involved in painting. In the political, it is about how political groups reacted to gyrations in the political situation.

Lenin had no idea revolution was going to happen in January 1917, by October his party had seized power to the astonishment, and disapproval of large numbers of its leading figures. This was workers’ power, the dictatorship of the proletariat, but not socialism or communism. How that could happen was still undecided, and it was the civil war combined with the failure of the post-war revolutionary wave, which isolated Soviet Russia. By Lenin’s death in 1924, Soviet Russia was still no nearer to knowing what it was. The party of the working class were in power, but the workers had been largely destroyed in defence of the revolution, and a new hybrid of a workers’ state and peasant based capitalism was developing. Its chances of forming a stable system were always slim.

In stark opposition to the historical facts that Groys leaves out of the exhibition, we are presented with a cogent myth. A piece of argument that is true to his own definition of sophistry in that captures the phenomenological picture of Stalinism. By this we can say that there was a point around 1928, when the state acted in the way that is homologous with the kind of artist that Groys uses as his template. Stalin indeed presided over the Soviet Union just as Avraamov had over Baku in producing his Symphony of Sirens. Yet millions were not killed, starved, enslaved or forced into wage labour as a result of Avraamov’s performance.

In the end Groys performs the ultimate paralogism, the willfull yoking together of separate categories – art and state power, based on a formal likeness. It is only when we do a gross act of phenomenology, and abstract or reduce actual history that we can entertain such a theory. Stalinism was the counter-revolution. The party through Stalin and his policy of Socialism in One Country actively shut down the alternative path of development the Soviet Union was experiencing during the 1920s. There was no immediate geopolitical threat, and in 1928 even Wall Street was still booming. Politically Stalin imposed a policy to neutralise his opponents and then reconstituted the most elemental of capitalist social relations – the wage labour relation, and universalised it. The absence of any discussion of exploitation from Groys’ account is glaring. It is even missed out in his account of left criticism of the USSR, which concentrates on dystopian criticism, that the Soviets treated people like machines, emptying them of humanity.

While Groys can be convincing on the strength of the argument he mounts, we need to use his words and categories against him. His account is sophistical by his definition but also ‘one sided’. As for the revolution itself, Groys has been using a monkey wrench to open a tin of beans.

References

- Groys, B., (2009), The Communist Postscript (Verso, London).

- Groys, B., (2011), The Total Art of Stalinism (Verso, London).

- Groys, B., (2008), Anti-Philosophy (Verso, London).

- Groys, B., (2016), Into the Flow (Verso, London)

Joe Sabatini is a member of the Red Wedge editorial collective, and edits Revolutionary Reflections for rs21 in Britain.