Enzo Traverso, Left-Wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, and Memory. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017. 312pp. $35 hardcover.

* * *

1. Utopia in Ruins

In Nikolaus Geyrhalter’s Homo Sapiens (2016) the first and last shots of the film are of the Buzludzha monument in Bulgaria – constructed by the Communist state to commemorate the secret formation of its forerunner, Bulgarian Social Democratic Party, in 1891. After the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in 1989, it was abandoned. Today its vast chambers, statues and mosaics are crumbling.

Geyrhalter’s 90 minute film is composed entirely of stationary shots of human-made buildings that have been abandoned to the elements. Shopping centers in Fukushima, abandoned theatres in Detroit, nondescript hospitals, office buildings, shoreline amusements parks flooded by the tides. There are no humans. Just the sounds of wind, rain, birds chirping or flapping their wings. A world without us that continues to experience itself. A gothic future both haunting us and haunted by us.

The Buzludzha is the only location to which we return. The first time we see the it is in the springtime; rain falls in through the disintegrating roof. The last time is during a winter storm, when its caverns and hallways are being flooded with snow as the screen fades to an empty white.

These opening and closing shots beg questions. Might the “end of history” we were all supposed to have witnessed with the fall of Communism, be something of a self-fulfilling prophecy? Is the human race possible without utopias?

Geyrhalter is asking far broader questions about humanity’s futurelessness. But he is far from the only filmmaker to use the torn down and disassembled socialist dream as a cornerstone for his stories. Many other filmic observations of the past twenty-five years have been far more pointed.

In Theo Angelopoulos’s Ulysses’ Gaze (1995) a dissembled statue of Lenin floats down the Danube River.

In Jean-Luc Godard’s Film Socialisme (2010), the dreams and manifestations of socialism are fractured and fragmented, unable to communicate with each other or themselves. The eighty-six-year-old Godard arguably did more than any other living filmmaker to integrate the methods of avant-garde film with a Marxist outlook. For him to make such an observation about the impossible reveals something very bleak.

The “end of the Cold War and the collapse of communism” along with the neoliberal turn and the rise of post-modernism, Enzo Traverso writes, “broke the dialectic of the 20th century.”(2) This is one of the pillars of the author’s stunning, painful and vivid Left-Wing Melancholia. He is not here implying that the regimes of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were genuinely socialist. They weren’t. But their existence was tethered to the utopias of the 20th century.

The democratic revolutions of 1989, unlike the historic revolutions that were “factories of utopia,” not only cut the tether but relegated utopia itself to the trash heap of useless memories (3). Even imagining utopia – arguably the whole a priori reason for an imagination – became worthy of sneering accusations of childishness. The end of “really existing socialism” pulled down other grand visions for the future – “democratic socialism, pan-Arabism, Third-Worldism.” All became anachronisms from a time before capitalism’s victorious teleology.

Traverso writes that the 21st century is defined by the “general eclipse of utopias.” (5) We were left with capitalist realism – an empty social shell devoid of both meaningful social progress and genuine poetry.

Says Mark Fisher, the late Marxist intellectual who first used the term in this sense:

Capitalism is what is left when beliefs have collapsed at the level of ritual or symbolic elaboration, and all that is left is the consumer-spectator, trudging through the ruins and the relics… capitalist realism presents itself as a shield protecting us from the perils posed by belief itself. The attitude of ironic distance proper to postmodern capitalism is supposed to immunize us against the seductions of fanaticism. Lowering our expectations, we are told, is a small price to pay for being protected from terror and totalitarianism.

2. From a World Without Utopia to Utopia vs. Apocalypse (or Utopia inside Apocalypse)

Traverso describes recent decades brilliantly. But a cultural dialectic has returned to the political graveyard. Capitalist realism isn’t merely faltering; it is cracking up the middle, its fragments tumbling in unpredictable directions.

Being newly born and highly uneven, Traverso could not have had the fodder to fully discuss this phenomenon when he started writing this book. Nonetheless is it here: a dialectic of utopian impulses that should not exist vs. a growing apocalypse whose void is palpable.

A socialist impulse as an organic development of the working-class, has returned (at least at the margins). The new socialist movement in the United States, an explosion of membership in socialist groups, personifies the impulse for an egalitarian, just and democratic world. In the United Kingdom the Labour leadership of Jeremy Corbyn has reignited the vision of a just and humane alternative to neoliberalism. It is an impulse that – as so many tiny groupuscules left to hang on for dear life forgot – is an organic product of an unequal, unjust and undemocratic world.

But the new socialist movement has come to life, in tandem with other old ideologies, amidst ruins. The new fascists personify existential annihilation (climate change, intensifying inter-imperialist competition, never ending “War on Terror”). All are reacting against the realism of neoliberal capitalism.

And the new -isms look back – in very different ways – because, as Traverso notes, “A world without utopias inevitably looks back.” (9)

2017 gave us, however virtually, the UFOs of a punch-drunk Left intellectual’s fever dreams looking across rivers of blood at sarcastic, cartoon fascist frogs.

Now, the challenge posed is whether the methodology of cultural memory and mourning Traverso so poignantly illustrates can be used to help us shape a new future without forgetting the persistent need to reckon with our past. Whether the mourning we still have left unfinished can pull us out of our torpor. And whether the defeats of the past still sting enough to propel us into becoming history’s revenge before the revenge of history swallows us whole.

3. Mourning and Melancholia

Modernity animated utopia (or vice versa) – from the French Revolution through the Russian Revolution and nearly to the end of the 20th century:

October 1917 immediately appeared as a great and at the same time tragic event that, during a bloody civil war, created an authoritarian dictatorship that rapidly turned into a form of totalitarianism. Similarly the Russian Revolution aroused a hope of emancipation that mobilized millions of men and women throughout the world. The trajectory of Soviet communism – its ascension, it apogee at the end of the Second World War, and then its decline – deeply shaped the history of the 20th century. (6)

But a crisis of ideas, political parties and unions followed the erasure of October. The intellectuals, eventually, turned on utopia itself (8). The labor movement and social democracy made ideological (not merely practical) peace with capital.

Mantegna, Lamentation of Christ (1480) and Che Guevara after his murder by the CIA in Bolivia (1967).

“The European left lost both its social basis and its culture.” (9) The nature of political tragedy changed. For much of the 19th and 20th century “iconic images of revolutionary mourning” moved the defeated to carry on the struggle. (41) This historical value of martyrs was traded for mere age value – the aura of time (distance) decoupled from its historical meaning (44). The destruction of socialist monuments denies even this auric age value (44).

What was left of the socialist movement and left culture found itself in a state of melancholia – despite the sects’ best efforts to clinically attach a permanent smile onto their faces.

The distinguished mental features of melancholia are a profoundly painful dejection, cessation of interest in the outside world, loss of the capacity to love, inhibition of all activity, and a lowering of the self-regarding feelings to a degree that finds utterance in self-reproaching and self-reviling, and culminates in a delusional expectation of punishment. (44, Freud’s description of melancholia)

Traverso opines that “we could define ‘left melancholy’ as the result of an impossible mourning.” (45) Impossible, perhaps, because the central animating impulse of socialism is the emancipation of the working-class, a class that still exists in itself, is still exploited, is still objectively capable of action and rule. But, the author reminds us, it is a class defeated not just in part but in total (however temporary or permanent this defeat may be).

Traverso, throughout his book, describes Gillo Pontecorvo as the filmmaker of “glorious” or even “victorious” defeats. The director of Burn! (1969 – chronicling a slave revolution on a fictional South American island) and The Battle of Algiers (1966 – a semi-cinéma vérité exposition of the struggle for Algerian independence) was a thoroughly 20th century filmmaker.

Pontecorvo was a communist who broke with official Stalinism over the Soviet invasion of Hungary and its repression of the 1956 Revolution. He remained committed to anti-colonial struggle. Although the heroes of Burn! and The Battle of Algiers are killed in the end, these films are an “incitation to fight.” (93) In both films defeat can only be temporary. Algeria will rid itself of the French. The insurrectionists of Burn! will continue the struggle against foreign domination.

The 1990s and 2000s tended to produce ghosts instead of martyrs.

It was Ken Loach who joined these ghosts with their corporeal ancestors and the social history of the 20th century. Land and Freedom (1996) – his Spanish Civil War film based in part on George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia (106) – a young woman is looking through her late grandfather’s effects and finds evidence of his time fighting with the Marxist POUM militia against the fascists in Spain. Loach, consciously or not, uses these “relics” of memory to connect the lost-in-time age value of the post-utopian 1990s with the martyrs of historic left tragedy.

But the film does not escape left melancholy. It cannot. In the end we are left with the hero’s granddaughter and a few old partisans and comrades in a graveyard.

Chris Marker’s Grin Without a Cat (1977 and 1993) shows the chasm between the dreams of Paris in 1968 – when Situationist posters demanded “All Power to the Imagination” as students marched and workers occupied factories – and the weaknesses that allowed those dreams to unravel. “We lived with the fantasy to storm the Winter Palace,” Marker noted, “[but] nobody ever thought of marching on the Élysée.” (101)

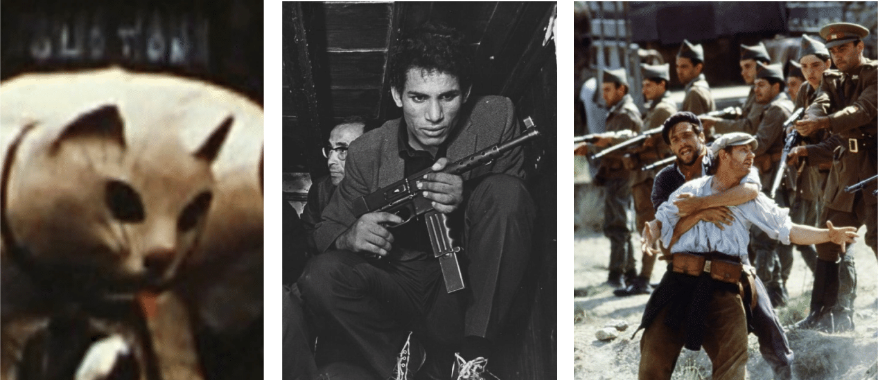

Chris Marker's A Grin Without a Cat (1977), Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers (1966) and Ken Loach's Land and Freedom (1995).

Or, as Traverso writes, “In Latin America, revolution was bloodily defeated; in the West, it never took place. It remained ‘the unending rehearsal of a play which never premiered.’” (101) The symbolic was insufficient. Cheshire revolutionaries retreated. And the worst of them became champions of post-modernism – the defenders of neoliberal capital’s cultural logic.

(First detour: Walter Benjamin)

Such an approach is both political and anthropological. It is, in this way, thoroughly Benjaminian, embracing a certain “tradition of left melancholy.” (45) Walter Benjamin, who once noted he was born under the melancholic sign of Saturn, the “star of hesitation and delay,” described Shakespeare’s Hamlet as the “paradigm of the melancholy man” (47). Hamlet is paralyzed by knowledge, perhaps paralyzed by an impossibility of mourning:

Melancholy betrays the world for the sake of knowledge. But in tenacious self-absorption it embraces dead objects in its contemplation, in order to redeem them. (47)

This “recollection of the past preceding its revolutionary redemption” is compared to the historic figure of the ragpicker – the poorest of the guild poor who sorted through the disgusting refuse of late medieval society, living in camps on city’s outskirts. (47)

The socialist writer (and we can add artist) is alone (47); an impossibility because they are animated by the collectivity of the working-class but still isolated by the nature of their work. Chris Marker could see the tragedy of the Cheshire revolution but could do little about it.

Melancholia for Benjamin comes before revolutionary action or consciousness – like standing before the churn of history and its debris in his famous meditation on Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus. The prescience of this image is in its acknowledgement that utopia itself comes from the recognition of contemporary despair.

As for the mourning, it takes the shape of the memory of hundreds of lost battles and revolutionary defeats from the Paris Commune on. It is that that gives left culture a gothic quality, drawing attention to the melancholic hue of history itself and, perhaps counterintuitively, making utopian futures possible. This faltered after 1989 (48, 50).

When communism fell apart, the utopia that for almost two centuries had supported it as a Promethean impetus or consolatory justification was no longer available; it had become an exhausted spiritual resource. The ‘structure of feelings’ of the left disappeared and the melancholy born of defeat could not find anything to transcend it; it remained alone in front of a vacuum. The coming neoliberal wave – as individualistic as it was cynical – fulfilled it.” (52)

(Second detour: ghosts and teleology)

Teleology was traded for ghosts. In the academy history was displaced by memory, the social replaced by its impossibility. “Marxism played a major role in the humanities when society was their dominant paradigm,” Traverso writes, “its eclipse became almost complete in the 1980s, when scholarly research shifted toward the paradigm of memory.” (56)

Paul Klee's Angelus Novus (1920), the left-wing intellectual raven from Pasolini's Hawks and Sparrows (1966), Albrecht Durer's Melancholia (1514).

The explanation of phenomena by purpose was “discredited” by both post-modern apologists and the history of Stalinist positivism. But this understanding of phenomena had not merely been an academic exercise. It animated working-class martyrs. The turn in the humanities toward memory “ironically” erased what the martyrs fought and died for.

For the liberal academic the images of partisans and Warsaw Ghetto fighters were mostly forgotten – even if the image of Auschwitz remained.

Abandoned by the “principle of hope,” our age of post-totalitarian, neoliberal humanitarianism does not perceive the past as a time of revolutions, but rather as an era of violence. (57)

The new came to life in a cultural context of seemingly declassed and decontextualized violence – a cultural condition once theorized as a new capitalism but one that was really just capitalism culturally triumphant.

4. Babylon Bolshevism

Marxism had, of course, its own kind of memory – now broken, now being re-assembled in the U.S. by a small army of antifas, Juggalos, democratic socialists, post-Trotskyists, post-Maoists and new Wobblies. The new left is, in one sense, like a stroke patient learning to talk again, speaking a hundred different languages – and unsure of the meaning of those languages.

“The monument of Tatlin to the Third International drew its inspiration from the biblical myth of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11),” Traverso argues:

that, as we know resulted in divine punishment for human beings guilty of a demiurgic dream. The Tower of Babel could not be finished and fell into ruin; its image was transmitted for centuries by a large iconographic tradition immortalized by the famous painting of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. (74-75)

In the metanarrative of post-modernism our Promethean Marxism was similarly punished for its hubris. Marxism’s many sins – a supposed determinism, Eurocentrism and a narrow focus on an idealized working-class – all lead to the Stalinist nightmare.

These accusations, of course, are wrong (or incomplete). Classical Marxism was not determinist, it was contingent. For its less Orthodox thinkers, Marxism adopted a (rightly) anthropological as well as activist attitude (also see Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht), and these thinkers did not see history as an automatic progression.

As Traverso describes Ernst Bloch:

Rather than a “cold utopia” depicting socialism as a future inscribed into the laws of history, Marxism was, in the eyes of Bloch, a social project routed into an anthropological optimism inherited from the Enlightenment; the long process through which humanity learns to rise up and walk upright. (70)

And as Benjamin famously wrote:

Just as the fascist historical imagination is a mythical construction, the revolutionary perception of time – its antipodal one – is shaped by memory, even if it is a “memory of the future,” charged with eschatological expectations. Walter Benjamin grasped this feature when he wrote that revolutionary movements were “nourished by the image of enslaved ancestors rather than that of liberated grandchildren.”

Far from being the deterministic caricature of its opponents (and its worst adherents), a “Marxism corresponding to our regime of historicity – a temporality withdrawn into the present, deprived of a prognostic structure,” Traverso argues, “inevitably takes a melancholic tonality.” (83)

5. Socialism, Bohemia, Avant-Garde

Modern socialism grew up (most importantly) with the modern labor movement but it also found purchase in 19th century bohemia, a social and cultural space that included many workers and unlanded peasants but also volatile petty bourgeois, declassed aristocrats, artists, poets and others turned vagabond by the tendency of capital to make every sacred thing profane – at a time when “[c]apitalism had firmly entrenched its Zivilization, but had not yet absorbed or replaced the old Kultur.” (121)

If, as Michel Löwy and others have argued, the cultural antithesis to capitalism (within capitalism) is the Romantic, the bourgeois and bohemian began as “positive and negative poles in the same magnetic field” (121) in which “the Bohemian represents the tramp of modernity.” (121) appearing most often, after the 1830 Revolutions, where the “‘persistence of the Old Regime’ [the pre-capitalist regime] is at its weakest.”

Like the Romantic, this cultural space was antithetical to a world in which everything was valued by exchange and utility (the capitalist world). It was “experienced by its followers as a space of freedom wrenched from the much more prosaic surrounding reality and as an anticipation of the liberation to come.” Traverso writes, “Its members display an irreducible dissatisfaction toward the present, totally lacking possibilities of compromise.” (123)

Today, of course, there is no escape from a digital and globalized present that permeates and maps everything – from hills in Venezuela to the Nevada desert around Area 51. Classic Bohemia was, in some way, a refuge for a “large intellectual proletariat… marginalized for political reasons and… national, ethnic, religious, or racial prejudices.” (125)

In this bohemia again recalls the Romantic intellectual alienated a hundred years earlier by the turn toward industrialization and the market. But the bohemian did so in an environment in which capital was already triumphant and consolidating its cultural dominance.

Scene from Le Chat Noir, a hub of 19th century Parisian bohemia.

The 21st century “hipster” – essentially over-educated and under-employed downwardly-mobile middle and working-class youth – echoes its bohemian and Romantic antecedents. But today’s cultural signs are far more rapidly reified and distributed. Nevertheless, just as bohemia produced socialist cadres (and profoundly shaped socialist culture) the milieus of maligned 21st century “hipsters” do so today.

This is why, in part, your Facebook friend is always complaining that the local membership of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is too “middle-class” and too white. They are no doubt right about the latter but likely misunderstand the (downwardly) fluid class character of the former.

Related to these phenomena is the avant-garde, the personified anticipation of future cultural developments. During the utopian 19th and 20th centuries the cultural avant-garde was transgressive. This transgression was closely identified with utopian dreams; usually progressive but sometimes reactionary, usually secular but sometimes spiritual.

The loss of utopia made the neoliberal and post-modern avant-garde “weak” – tinkering with cultural signs without opposing the dominance of capital or its material and cultural debasements. Just as “progressive” neoliberal politicians dared only to tinker with the edge of bourgeois economics, the weak avant-garde grew terrified of “grand narratives.”

Worse, such cravens pretended to be the intellectual vanguard.

Conversely, the anti-avant-garde stance of some Marxists, particularly among certain sects and economistic social democrats, is blind to the nature of the avant-garde and bohemia and the historic connections of both to Marxism and socialism; that the avant-garde is an organic product of culture in a capitalist system of novelty and change and that this center of cultural experimentation, drawing from all social classes, frequently finds itself in opposition to the status quo.

(Third detour: Marx and Bohemia)

As Vladimir Lenin described Marx in a famous “biographical sketch,” Marx “continued and consummated the three main ideological currents of the 19th century” – “classical German philosophy, classical English political economy, and French socialism combined with French revolutionary doctrines in general.”

The latter of these, “French socialism,” is less often described in detail when Lenin’s description is unpacked. 19th century socialism in France overlapped with bohemia in significant ways.

As Traverso observes, Marx describes French socialist circles in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1844) as a “kind of countersociety in which workers could establish communal, brotherly relationships in the world… The purpose of their meetings was propaganda and the organization of possible revolutionary action, but the means they had chosen – their meetings would often develop as very convivial dinners – tended to be a goal in itself (the community). The description Marx gave of these meeting had a strong Bohemian flavor: ‘smoking, drinking, eating.’”(131)

Marx and Engels, however, were critical of the volatility and adventurism present amongst Bohemian intellectuals (128), a social category that included proletarians but also the petit-bourgeois and “lumpen proletariat.” Regardless, bohemia transmitted socialist ideas, scientific but also utopian, among workers, intellectuals and artists.

(Fourth detour: Gustave Courbet and 19th century socialism)

The Romantic painter turned Realist, Gustave Courbet, is emblematic of this milieu.

Courbet was a socialist and an admirer of Fourier. In several texts and letters, he presented himself as a socialist, a democrat and a republican, “a supporter of the whole revolution.” In fact, he was a kind of anarchist inspired by the philosopher Joseph Proudhon.

Courbet famously proposed that the artists of the Paris Commune destroy the Vendome Column and replace it with a revolutionary monument. This resulted in his imprisonment after the Commune’s defeat. But unlike some of his contemporaries, Courbet’s political and artistic life were fused. His socialism, his former Romanticism and his Bohemian life, were of a whole.

The toppling of the Vendome Column.

Courbet translated his socialist and democratic impulses to painting by creating radically equalized compositions and painting subjects of working-class and “every day” life rather than presenting grand mythologies or portraits of rich and powerful people. This is not to say his paintings were not “grand” or without mythologies of a more socialist kind. Burial at Ornans (1851) is a massive painting consisting of numerous portraits of Courbet’s fellow citizens (equalized at a funeral). Future paintings were allegories for the ups and downs of 19th century French revolutionary struggle.

Of his bohemian life, Courbet wrote in 1850:

In our civilized society, I need to live like a savage. I need to go far away from governments. My sympathies are with the people. I must speak to it directly, draw my knowledge from it, live by it. This is the reason for which I choose to embrace the great, independent, and vagabond life of Bohemians. (133)

The Romantic dialectic, observed by Michel Löwy, in capitalist culture was born of the contradiction between the pre-capitalist intelligentsia (trained to value things by their qualities) and rising capitalism (tending to value things by exchange and utility). Capitalism’s continued need for an intelligentsia (and artists) repeatedly recreates the Romantic dialectic. The material and “spiritual” needs of artists, throughout the utopian 19th and 20th centuries, pre-disposed artists to both Romantic and material opposition to capitalism.

Because artists are, as artists, “middle-class” in relationship to production, but middle-class speculators who come from multiple class backgrounds, who speculate less in terms of money than cultural valorization, they seek to carve out or participate in spaces similar to that of 19th century bohemia. These spaces are sites of ideological contestation and volatility.

This dynamic can be poo-poo’d by vulgar Marxists but it has been an organic aspect of capitalist culture.

(Fifth detour: socialists in Bohemia)

This is not to say it isn’t contradictory. Traverso writes:

In the works of Marx, Courbet, Benjamin and Trotsky, Bohemia appears as a place of revolt that tends to split into two antipodal camps, a revolutionary one, going from the July Monarchy to Surrealism, from Blanqui to Mayakoskski and Breton; and reactionary one, going from the Bonapartist circles in 1848 to the Italian Futurists, Céline, and fascism. Baudelaire, in between both, is witness to a revolt that has not yet found its way, and is likely to go in either direction. (142)

For example, as Traverso shows, Trotsky’s attitude toward bohemia shifts dramatically according to what he perceived as the immediate tasks of the socialist movement. As a leading figure of the Bolshevik government he tended to be somewhat hostile to bohemia. As an exile (before and after October) Trotsky led a bohemian life and was in large part sympathetic to his fellow bohemians.

A similar striking contrast exists between his defense of “aesthetic nihilism” in the texts of his last Mexican exile and the essentially pedagogical vision of art he defended in 1923 in Literature and Revolution, going as far to make a discreet apology for “revolutionary’ censorship. In his famous manifesto “For a Revolutionary and Independent Art,” written in 1838 with André Breton (and to which Diego Rivera added his signature), Trotsky launched the slogan “absolute freedom in art,” and advocated among all the revolutionary tasks in the field of intellectual creation to “establish and secure from the start an anarchist regime of individual freedom. No authority, no constraint, not the slightest hint of command!” (148)

We should be clear. While Trotsky responded to changing circumstances, when he did not favor absolute freedom for art he was simply wrong, perhaps turning the “necessities” of the Russian Civil War and post-revolutionary crises into virtues (as too many Bolsheviks were wont to do).

But Trotsky wasn’t the first to span these contradictions. Even Marx lived what could only be described as a bohemian life in London exile while, at the same time, pointing out the ideological limits of that milieu (144). Traverso quotes the report of a Prussian spy:

He lives in one of the worst and cheapest of the London districts. He occupies two rooms. Neither of them is clean nor furnished with any equipment in good state, everything is broken, torn to shreds, each object covered with a thick layer of dust. Manuscripts, books and newspapers, his wife’s sewing, handless cups, dirty towels, knives, forks, lamps, an inkwell, mugs, pipes, tobacco ash lie, next to children’s toys, on the same table. When you enter the room the smell of tobacco and smoke overpowers you to the point that you feel you are groping in a cave, until you get used to it and take care to move some objects in the haze… a three-legged chair... is offered to the visitor, but the children’s food has not been removed and you risk staining your trousers. But this does not embarrass Marx or his wife. You are welcomed in a most friendly way and are cordially offered a pipe, tobacco and the rest. Then an interesting conversation starts which makes up for all the domestic shortcomings and makes the discomfort bearable.

The Prussian spy’s final observation is key to understanding left-wing bohemian artists (at least the poor and working-class ones). The squalor is redeemed, for an (all too brief) moment, by intellect and art. But only revolution can truly overcome that squalor. Without the final redemption, without the utopia that redeems that squalor once-and-for all, the avant-garde of the 21th century turned away from both revolution and art itself. Many became dull managers of cultural signs, quislings for corporations and gentrification. And the better ones hate themselves.

6. Hegel and Left-Wing Melancholia: A Note

While Marxism was not deterministic it was marked by its origins, Hegelian and otherwise. For example, Marxism is not, as a theory, Eurocentric. But Marx’s writings are overwhelmingly focused on Europe. “To blame Marx for ‘Eurocentric’ views means, in some way, to blame him for having lived in the 19th century and for having inscribed his thought in the intellectual and epistemic horizon of his time.” (152)

Marx himself “warned against the transformation of the ‘historical sketch of the genesis of capitalism in Western Europe into an historico-philosophic theory of the general development, imposed by fate on all peoples, whatever the historical circumstances in which they are placed.” (153) But this did not prevent, as Traverso notes, the turning of Marxist thought into a “positivistic” philosophy, first in the 2nd International (led by its “Pope” Karl Kautsky) and later in the Stalinized Communist International (153).

Hegel’s mistaken approach to history cannot simply be corrected by “replacing” the “idealist” determinant for a “materialist” dialectic. (154) Hegel’s history problem, in other words, was not simply his idealism but also his (related) iron teleology. The idea of sequential progress could not survive in the era of left-wing melancholia (and opened up the left to one of the post-modernist’s favorite lines of attack).

7. Missed Encounters: CLR James and Adorno

Part of what saves the Marxist theory from the limits of its origins have been thousands of theorists and activists who have revised it. But these contributors, blinded by their own narratives or sectarian orientations, have not always successfully communicated with each other. We do not pretend to be immune.

A striking example from Traverso’s book is the section on the melancholic gazes of CLR James and Theodor Adorno. The latter focused on the totalitarianism (fascist and Stalinist) in Europe. The former on colonialism. Despite the symmetry between these two phenomena – the fact one could describe the barbarism of fascism as colonial practices coming “home” to Europe – the thought of these two Marxists (of different sorts) remains largely unconnected. Adorno and James met at least twice, but they were ultimately not meetings of the mind.

And yet, the affinities are there. Edward Said, Traverso notes, writes in Representations of the Intellectual, that the two were “’contrapuntal’ thinkers who rejected conformism and escaped canonical views,” and both “immigrated to New York in 1938, at the edge of the war, and lived in America until the advent of McCarthyism.”

Both were also, from different angles, convinced that the terror of fascism, the carnage of the death camps, were not an aberration from capitalism’s trajectory. They were woven into the very fabric of the system.

Here is the Martinican poet and communist Aimé Césaire in his 1950 Discourse on Colonialism.

People are surprised, they become indignant. They say: “How strange! But never mind – it’s Nazism, it will pass!” And they wait, and they hope; and they hide the truth from themselves, that it is barbarism, the supreme barbarism, the crowning barbarism that sums up the daily barbarisms; that it is Nazism, yes, but that before they were its victims, they were its accomplices; that they tolerated that Nazism before it was inflicted on them, that they absolved it, shut their eyes to it, legitimized it, because, until then, it had been applied only to non-European peoples; that they have cultivated that Nazism, that they are responsible for it, and that before engulfing the whole edifice of Western, Christian civilization in its reddened waters, it oozes, seeps and trickles from every crack.

We might venture to say then, for today’s purposes, that any viable critical theory – be it literary or otherwise – needs to concern itself with the anti-colonial struggle. And vice versa. The links are there, but they must be emphasized, examined and explored. Particularly today when the lack of a viable alternative to capital and racism continues time and again to undercut our ability to see linkages between exploitation and oppression, hyper-consumerism and neo-colonialism. The historic rift that has historically caused “Western Marxism” and left-wing Third World liberationists to speak in different tongues is, ultimately, one that necessarily must be bridged.

So too must the different postures struck by Adorno and James in relation to culture itself. On one end Adorno, the lover of the classical and high avant-garde with nothing but disdain for the popular, on the other James, whose defense of popular culture’s redemptive qualities and its reality as a battleground for ideas presupposed to a degree that of Stuart Hall.

How might we then square James’ reading of Moby Dick with the world literature of today? Traverso provides an engaging summary of James’ Mariners, Renegades and Castaways, his exegesis of Melville’s high seas literary masterpiece, in which the monomaniacal Ahab becomes stand-in for modernity’s death drive, bringing down with him a crew from across the planet thrust together by the motions of accumulation and extraction. Most salient here is James’ observation that the same forces that drown the crew are also what force them together, to pidgin-ize their communications with each other, to find a method of creating something total out of worlds stacked roughly on top of other worlds.

There is no shortage of stunning literature pulling on these themes today. But so much of the praise and accolades showered (rightly, we should stress) on Zadie Smith, Edwidge Danticat, Junot Diaz, seem to elide the point. That in a world of constantly shifting and widening diaspora, in which migratory human beings become vectors of different worlds, there remains an urge – diverted but not stamped out – to discover the universal in the particular.

8. Missed Encounters Part II: Melancholic Spheres

For all the grace and urgency with which Traverso weaves the romantic revolution through art, literature and film, it is something of a disappointment that he does not do so with music in Left-Wing Melancholia. This does not weaken the book by any stretch. Nonetheless the absence points up many questions about the aesthetic and outlook of a modern left-wing melancholic searching for their springboard into a practical poetics.

For what makes music unique in relation to the other realms of creativity is its relationship to time, its ability through sonic dynamics to create a sharp awareness of when one is in relation to the immediate past and future. The musician is a funny kind of anti-hypnotist. They foster a specific mode of listening that plays on the listener’s awareness of what they are hearing now and how it relates to what came directly before as well as an anticipatory uncertainty for what will come next. It is, at least potentially, a reminder that the past necessarily must generate a future.

The list of iconoclastic or experimental musicians allied to revolutionary politics, who sought to use their peculiarly slanted relationship to time as a kind of social sensitizer, is long. And despite what Adorno may have thought of jazz, it is no coincidence that so many have come since the rise of that pillar of popular music without which virtually no modern sonic expression would be possible.

Gil Scott-Heron, Robert Wyatt, Patti Smith, Fred Ho, Mark Stewart, Cornelius Cardew. These are musicians who, in one way or another, create or created sounds prefiguring a future by reference to what had already taken place, looking backward not out of nostalgia but to create a tunnel for Benjamin’s “tiger’s leap into the past.”

Gil Scott-Heron.

Many have also been quite keen to the post-communist malaise, feeling it themselves and attempting to rifle through it in a way to push out. In his 2006 collection of essays Psychic Soviet, Ian Svenonius writes of the “cosmic depression” that overtook the world after the fall of the USSR, positing a mass psychogeographic doom that made the world appear futureless. There is perhaps here another missed connection, even as Svenonius’ explanations veer into the odd and fractured realms of Jungian psychology and archetypes.

Svenonius is, as any hipster will tell you (pseudo bohemian or otherwise), also the iconoclast’s anti-rockstar, the anti-authoritarian Marxist theorist working his way through the contradictions of capital through pop music. Frontman and conceptualizer of Weird War, the Make-Up, Chain and the Gang, and the seminal Nation of Ulysses, the best of Svenonius’ music rails with almost messianic intensity against the hollowness of the commodified moment. And though his points of reference may range from gospel to free jazz to garage rock, he and others like him attempt to not merely observe these sounds under oxygen-proof glass but to rediscover something.

The video for Algiers’ song “Irony. Utility. Pretext.” is shot in Bulgaria’s Buzludzha. Three of the band’s members sing, strut and dance their way through the abandoned monument, the deteriorating statues and mosaics dedicated to a cancelled red future towering over them. If this is one of the sites where utopia died, then perhaps an irreverent breakdance on the grave might, at the very least, allow us to wake those parts of the dream that are merely sleeping.

9. After Left Melancholia

What then, as always, is to be done? We can share some empty phrases, some vague truisms intended to motivate but end up so broad as to be almost useless. Such has been, for far too long, the modus operandi of a left that has acclimated to the wilderness without realizing it.

It won’t do. We cannot remain true to history, or the vision of emancipation that has been central to the working class movement, by ignoring just how colossal our defeat has been, just how much has been denied of us. History’s motion is becoming bald-faced and evident once again, even brutal and merciless. This much is true. And with this motion there are indeed new opportunities, new challenges and responsibilities for building a vital and strong left. We cannot, however, hope to meet these challenges without daring to face the reality of our past, to ragpick and salvage something from the wreckage – including those parts of our history and methods we might have forgotten.

It has by now entered into left mythology that Joe Hill, the martyred Wobbly organizer and troubadour, told the world “Don’t mourn. Organize” on the eve of his execution. He said this about himself, however. This is an important distinction. For as selfless as this invocation is, it was never intended to apply to all defeats under the sun. Despair is nothing to wallow in, but ignoring it provokes a nervous exhaustion in the subject.

Have we really mourned? How many revolutionary funeral dirges have we repressed rather than sing for fear of realizing the horror? The urgency of the moment tempts us to run roughshod over these questions, rushing to get ahead of the challenge and in the process deflecting our ability to fully grasp it.

Yes, we must pivot one last time toward emancipation. The times – of returning fascism, of looming nuclear conflict, of a planet shuddering to rid itself of us – demand it. The geography of a left that must grieve and fight simultaneously is a difficult one to map. Without it, those of us who create and invent and deserve to reshape the world (which is to say all of us) are left feeble. If any even mildly utopian future is possible, we must fully grasp the disaster of our past.

A contradiction? Absolutely. But since when have Marxists – or artists – shied from contradiction?

This piece appears in our fourth issue, “Echoes of 1917.”

Red Wedge relies on your support. If you like what you read above, consider becoming a subscriber, or donating a monthly sum through Patreon.

Alexander Billet is a writer and founding editor of Red Wedge. His work has also appeared in Jacobin, In These Times, the International Socialist Review, Marx & Philosophy Review of Books, and elsewhere.

Adam Turl is an artist and editor at Red Wedge. Turl’s recent exhibitions include Thirteen Baristas at the Brett Wesley Gallery (Las Vegas) and The Barista Who Could see the Future at Gallery 210 (St. Louis). He is an adjunct instructor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.