George A. Romero is dead. And much as some of us would like it, the director of the most iconic zombie horror films of late capitalism will not be rising from the grave to walk among us. But the ravenous consumption that we see in his creations – of flesh, of our sanity, of our hope for the future – will continue. Unless it is brought to its knees then late capitalism has all but assured this.

The interview below with author and film studies professor Tony Williams – one of the very first articles to appear at Red Wedge – was conducted by editor Adam Turl and appeared on the site in October, 2012. Williams has written extensively about Romero’s independent and radical films. His books include Hearths of Darkness: The Family in American Horror Film (1996) and The Cinema of George A. Romero: Knight of the Living Dead (2003). Most recently he edited George A. Romero: Interviews (2011). We reprint the interview here, almost five years later, in tribute to Romero and his film legacy.

* * *

Adam Turl: George Romero is most known for Night of the Living Dead (1968) and for revolutionizing horror movies. It is often added that he came of age as a filmmaker during the “tumultuous” 1960s and 1970s. You argue, however, that Romero is important as an independent filmmaker in general – a filmmaker whose work is critical of capitalism and consumer culture.

Tony Williams: You have to see George in the context of the 1970s when it was possible to do independent work without being under the control of the studio system and still get it distributed. During the sixties and seventies it was possible for directors to make their own special brand of genre films and get them distributed either by the major companies or independent distributors. This was the time when directors such as Larry Cohen, Wes Craven and Tobe Hooper emerged and were able to make their films on low budgets and find distributors such as American International and even major studios who would release their films to a very diverse exhibition field. This would not only include theater chains but also drive-ins, independent art cinemas and film societies. It was possible to have some degree of independence and expect the film to be seen by a wide audience.

Remember Jonathan Rosenbaum's definition of Orson Welles as an “independent filmmaker who just happened to be working in Hollywood.” During his Citizen Kane period, he had a unique contract that guaranteed him a high degree of independence that would never be repeated. His films were regarded as a threat to the corporate Hollywood studio system of the time – as they are now. It is not coincidental that George is a great admirer of Welles.

Turl: One of the threads in your first book on Romero is his intuitive use of naturalism. You refer to Emile Zola but also American literary naturalism. You address three things. One is the question of determinism versus a more dialectical relationship between characters and environment. Another is the question of the “crowd.” For example, in Zola’s Germinal, as you recall, “female rioters castrate a butcher who has been sexually exploiting them for years and proudly display their trophy.” Thirdly, you raise the idea of a “gothic” naturalism.

Williams: George is an intuitive director. He does not consciously think about these things like critics do! To this day he has never read Zola. Nevertheless, all these elements are present in his films since they are part of the cultural tradition he works in and subconsciously responds to. As I write in the 2003 book, both George and Stephen King grew up on EC Comic Books of the 1950s that have a definite naturalistic undercurrent.

Tony Magistrale has demonstrated conclusively the influence of naturalism on King. Thus it was no accident that both King and Romero collaborated on Creepshow – a deliberate homage to EC Comics. Andrew Britton and Robin Wood firmly believe that classical Hollywood cinema intuitively responds in different ways to the American cultural tradition -- and you have to remember that Zola directly influenced American naturalism as translations of his works from the 19th and early 20th century show. The “Gothic” is a key concept in American literature, so it is not accidental that Stephen King's The Shining places the Overlook Hotel in this context. George has his own concept of “the Gothic” that he creatively responds to. He provides reasons for the phenomenon in his work and never uses it as a concealing device or something that just expresses hesitation.

Turl: Can you say something about EC Comics – and the cultural and political role it played in the 1940s and 1950s – as well as discuss how it influenced Romero?

Williams: As I mention in the book, the EC Comic Book tradition dealt with taboo subjects in 1950s America such as racism, economic exploitation, and the Korean War debacle that could not have been expressed openly then. Because they were comics, this EC tradition was beneath the notice of McCarthyites. Yet it expressed a very important radical undercurrent at the time, something that does not exist in today's comic book films as the recent problematic Batman movie shows. The style influenced George in many ways, most notably in the very relevant social criticism that underlies all his films.

Turl: In more than one interview Romero said he was less influenced by other filmmakers than he was visual artists – in particular the great Spanish painters. Goya painted during the transition towards realism and later employed what you could call a sort of Gothic naturalism in his war etchings and paintings of Napoleon’s invasion of Spain.

Williams: This is a subject I've not fully explored but the link does not surprise me. Both Michael Powell and the cinematographer Jack Cardiff were influenced by painting. One of George's favorite films that he competed with Scorsese in renting on 16mm in the sixties was Tales of Hoffman by the Archers. Any worthy director who aims at a particular type of visual expression has a knowledge of painting.

Turl: Night of the Living Dead (1968) eventually became a mainstay in the midnight movie circuit and a critical success in Europe. People read a great deal of political meaning into the film – in particular surrounding the character Ben (played by Duane Jones), the Black protagonist shot down in the film’s final minutes. Romero has often said that much of the politics read into Night was unintentional on his part. But the whole movie seems pregnant with political implications.

Williams: Yes, I've read what George says about the subject several times. But no film can escape its social and historical context and Night is one of them. It expresses George's constant theme: the lack of communication and co-operation and how this can eventually destroy or decimate people. As many critics have shown, the film is allegorical and relates to a particular context. Ben is Black and Harry is an arrogant WASP (but is right about the cellar). One of the merits of the film is its depiction of complexity and how rigid attitudes, whether connected to race and class, hinder any movement towards successful resolution. The battle in Night exists on two fronts with two warring camps, inside and outside.

Turl: Night was made on a pretty small budget financed by Romero and his friends in Pittsburgh. For the most part he has actually been based in Pittsburgh and now Canada. How do you see the relationship between Romero’s actual material independence and the content of his movies? Romero also argued the space for independent films has shrunk since 1968, saying something along the lines of “Hollywood is dead, unfortunately its distribution system isn’t.”

Williams: In Rusty Nails’ documentary, John Carpenter regrets tempting George to work in Hollywood. Monkeyshines suffered from interference although it is a good example of what George could have done had he chosen to remain in the system. The Dark Half is professionally made but adds nothing to George's prestige. Day of the Dead lost half its budget before filming commenced but is still a good achievement. Two interviews conducted by Dennis Fischer have George speaking about interesting projects that could have been made that got discarded. The relationship between material independence and content is often very complex and one cannot make rigid judgments about that.

However, the Tales From the Darkside television projects placed George in a very subordinate role so he had to break from his producer Richard Rubinstein to regain the independence he lost. At the same time, Rubinstein was a positive force in the making of Dawn of the Dead, Knightriders and Day of the Dead. George’s quote refers to the spiritual death of Hollywood. It still exists as a corporate body but much worse than in the past when there was some degree of creative autonomy. Reagan's presidency resulted in the collapse of the 1948 monopoly ruling that separated production, exhibition and distribution. We are now back in the old Hollywood mode of corporate control of distribution that will not allow for the appearance of independent commercial work that George's films and others (Cohen, Craven, Hooper, DePalma etc.) allowed. It is the old rigid straitjacket but with less diverse product due to inflated costs of filmmaking.

Turl: Immediately after Night of the Living Dead began to make money he made two very different films – There’s Always Vanilla and Jack’s Wife. What was the thrust of these so-called “lost” Romero films?

Williams: George has dismissed Vanilla for several reasons – artistic and personal. But I think it is a very underrated film dealing with the collapse of the counterculture and “selling out” by the younger generation. Jack’s Wife is an early feminist film but not something that would be applauded by most current feminists. It is very much a film of its time in line with the works of Betty Friedan and others.

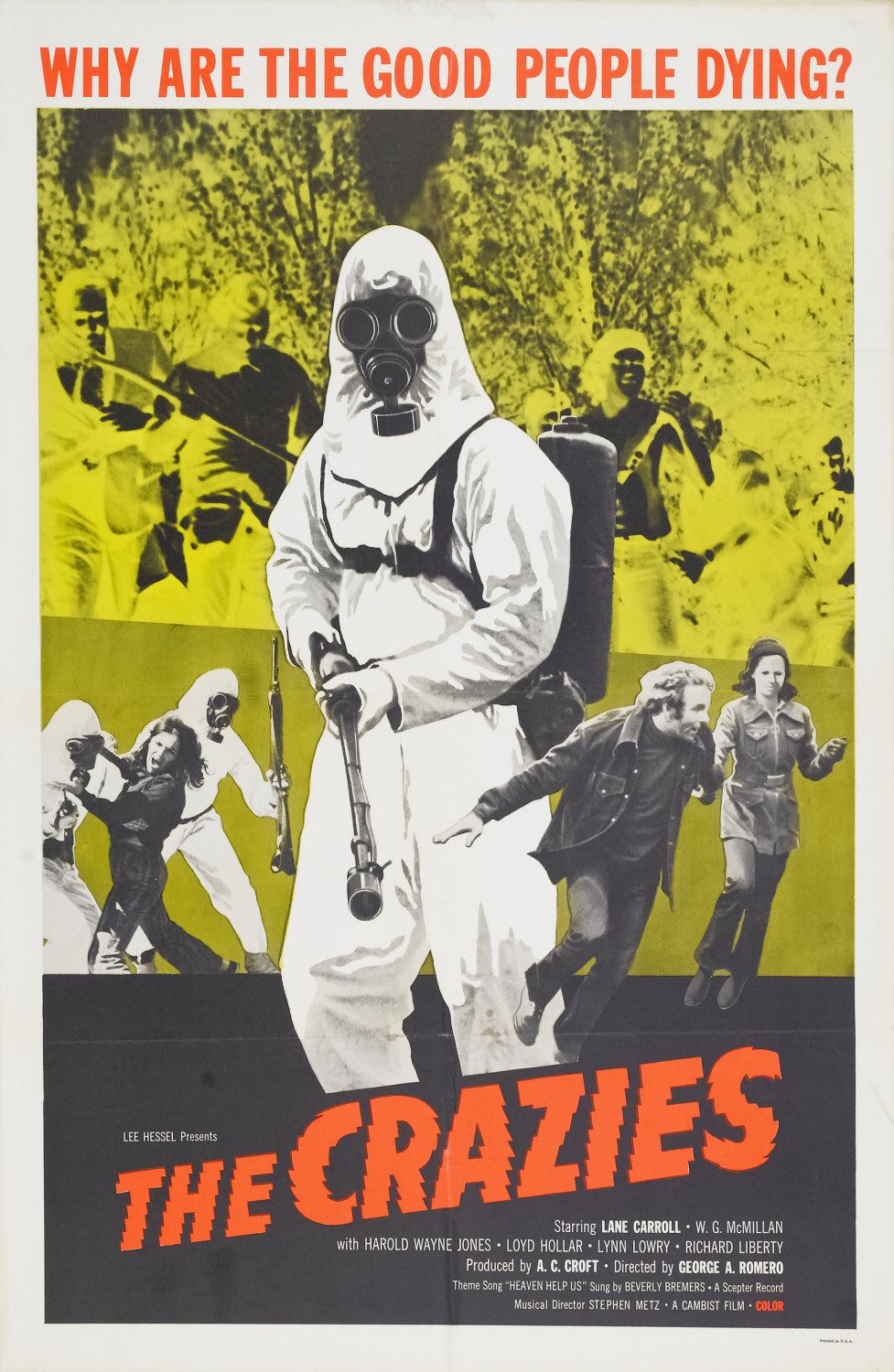

Turl: Romero’s fourth movie was The Crazies (1973) – a science fiction disaster film that dealt with the Vietnam War as well as the question of sanity in insane social circumstances. A biological weapon is spilled in a small town’s water supply that causes people to become insane. The military is sent in to contain the townspeople. How does the movie prefigure the theme of social disintegration that Romero later completes, as you argue, in Dawn of the Dead?

Williams: The Crazies is a film ahead of its time in depicting the callousness of the government and the ruthless attitude of the military. George could remake it with Wesley Snipes in the role of Barack Obama sending drones out to nuke any Americans protesting against their subordination to authoritarian control – especially with the virtual abolition of the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, habeas corpus, and the removal of citizenship from any American deemed a threat. I suppose Kathryn Bigelow has already begun her version of The Man Who Shot Bin Laden that will have no connection with John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – and will feature Hillary Clinton and Michelle Obama urging “The Great Pretender” to “do the right thing.”

So you won't need any “contamination” explanation since the contamination comes from outside very much like Robin Wood’s re-definition of the seventies horror film as “the monster threatened by normality” rather than “normality threatened by the monster.” It is George W. Bush who said, “you’re either for us or against us.” Now anyone who protests against the erosion of democratic rights and blows the whistle becomes the monster – as Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning know. When questioned about his erosion of the Constitution, Obama said, “trust me,” a well-known Hollywood term meaning “fuck you.” I remember that during the threat of avian flu George W. Bush relished using the military for the purposes of “quarantine.” I guess he thought the guys needed target practice like the rednecks in Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead. History has a worrying habit of catching up with George Romero’s films.

Turl: The original Dawn of the Dead (1978) was the second of what was to be three – but became more – “living dead” movies. You argue that it borrows even more heavily on the EC Comics tradition as well as naturalist literary themes as the main characters are constrained by social roles and structures. At the same time there is some hope for social change as two of the main characters – Fran and Peter – are able to escape those roles and redefine themselves. Early in the movie we see a police raid on a mostly Black and Latino public housing complex. Later the film’s main characters famously take refuge in a giant shopping mall.

Williams: Violence and consumerism appear in that frenzied shopping spree in Zola's Au Bohneur Des Dames (“The Ladies Paradise”). You and your readers are fully versed in the links between violence, racism, and consumer capitalism that I need not elaborate on here. Unfortunately, the appalling remake of Dawn of the Dead by Zack Snyder ignores all this, as French scholar David Roche remarked in his brilliant manuscript comparing seventies horror films to their compromised remakes (that I've just reviewed and urged publication of). You'll find an article by David dealing with both Dawns in Horror Studies 2.1 (2011): 75-87 that I highly recommend.

Turl: You argue there is a sort of radical pessimism in Romero’s work but that it doesn’t preclude hope necessarily. I think an example of this might be Romero’s 1981 movie Knightriders – in which people attempt to live a moral and ethical life separate from Ronald Reagan’s America. They adopt a code of medieval chivalry and even hold events in which they joust on motorcycle. Over time, however, tension grows between the code they adopt and the pressures of living within society.

Williams: Knightriders is George's allegorical version of the type of filmmaking he would like to do and the demands of the system. It is very much a film made in the mode of Howard Hawks, a director he admires. His statement resembles that of Robert Altman when he described himself as a “cynical optimist” expecting rain to fall in a desert. Why continue working if there is no hope?

Turl: Day of the Dead was the third installment of Romero’s zombie films. It takes place mostly in an underground bunker of soldiers and scientists and is widely seen as a reflection on Ronald Reagan’s reheated Cold War. The original script was even more ambitious with plans for armies of the dead to be sent to war against each other. I always thought it was one of Romero’s more pessimistic movies. You have a different point of view. I was hoping you could explain that here.

Williams: The ending is deliberately ambiguous in the best traditions of art and independent cinema. You bring to it what you think it might be.

Turl: I recently watched Romero’s film Bruiser (2000). You write, “the films of George A. Romero oppose the current monolithic Hollywood system both formally and thematically.” The corporate magazine in Bruiser – where most of the main characters work – could easily be a stand-in for Hollywood. What does it say about that world that it drives the main character to be, essentially, a serial killer?

Williams: Look at the various reports of shootings in America, of people going berserk in an uncaring system aided by the access to guns. You either go crazy and violent or try to find some radical alternative and think and behave differently.

Turl: In 2005 Romero made a fourth zombie movie – Land of the Dead. Since then he has made two more -- Diary of the Dead and Survival of the Dead. Land of the Dead had a fairly large budget and some big-name actors like Dennis Hopper. It was seen as a movie that dealt both with social inequality as well as the most recent wave of U.S. militarism after September 11, 2001. It was a big movie with big content. Diary and Survival seem almost intimate in comparison.

Williams: In his last two movies, George returned to the world of low-budget independent filmmaking he is most happy with. Despite the fact that I think Land of the Dead is a very good film, George was frustrated by a system that, on the one hand, provided funding to use Dennis Hopper and Asia Argento, and on the other refused to allow him to use his cameraman from Bruiser because he didn't have the right kind of qualification.

That was the last straw for George. He permanently relocated to Toronto after that, remarried, acquired Canadian citizenship, and is quite happy relating to many friends and colleagues “far from the maddening crowd” of the Hollywood machine and the corporate studio heads who have no idea of the type of cinema he wants to make and therefore instantly reject it. Larry Cohen is also content writing screenplays, working on treatments and waiting for better times. You should look at Larry's website where he has copies of scripts he has written but never filmed such as The Man Who Thought He Was Hitchcock. After a while one reaches a limit where not making a lot of money in the system and just being creative and independent is what really counts in the end.

Issue three of Red Wedge, “Return of the Crowd,” comes back from the printers in July. Read more about it and watch a video here. Want a copy? Order, subscribe, or become a patron.

Adam Turl is a writer, artist, and editor-in-chief at Red Wedge. Turl's most recent exhibitions include 13 Baristas at the Brett Wesley Gallery in Las Vegas, Nevada (2015) and Kick the Cat at Project 1612 in Peoria, Illinois (2015). He was awarded a residency at the Cité internationale des Arts in Paris, France in 2016. His next major project, The Barista Who Could See the Future, will be part of a group show with Lizzy Martinez and Stan Chisholm at Gallery 210 in St. Louis, Missouri in the fall of 2017. He is also an art critic for the West End Word and co-organizer of the Dollar Art House. To learn more visit his website evictedart.com.

Tony Williams is professor and Area Head of Film Studies at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. He has published widely in the areas of horror and American independent cinema, including the book Hearths of Darkness: The Family in the American Horror Film.