For the many who stare perplexed at the phenomenon of giant monster movies, the driving question is: what’s the appeal? For those of us who belong to the fandom, the old answers are necessary in response: we should not be compelled to justify what we enjoy; the genre hits a note of nostalgia for some of us; there is something inherently enjoyable about watching giant creatures level a cityscape; the lost art of rubber suits and detailed miniatures is something we ought to respect in and of itself; and so on. But is there something more going on here, something underneath the text?

At the outset we must dispense with the idea that there is such a thing as “pure entertainment.” Many respond to these kinds of inquiries with the old adage, “You are reading too much into it, it is just meant to be entertaining!” There is a lot to unpack in this statement, suffice it to say that something is entertaining as a consequence of its ability to communicate to a population of people in a specific context, making said entertainment product inherently ripe with social commentary as a consequence of its conditions of production. This is to say, playing to an audience’s simple entertainment factor implies that we are communicating with them about things they know, and in the last estimate all we know is derived from the social context from which our very identities have been developed.

Nonetheless, there is something even more meaningful going on in any kind of fiction which takes place between the lines of a text. In his infamous work of literary theory, The Political Unconscious, Fredric Jameson argues for a distinction between “empirical texts” — the very works of fiction under discussion, such as specific films or novels — and the “master narrative” underlying them. In these formulations individual “empirical” texts ought to be utilized to construct “master narratives of the political unconscious.” It is the task of the literary theorist to “detect and to reveal . . . the outlines of some deeper and vaster narrative movement” which corresponds to the broader social structures from which the “empirical text” derives its meaning. This is to say that, whatever the artist’s intent in producing such a text, there is underlying it a social knowledge and perspective on the artist’s social context. Thus, all texts are inherently political, and contain at least some degree of social critique.

All the better then, when there is a joining of this unconscious structure with the artist’s drive to say something, to present a critique of her situation, broadly speaking. This is not to say that texts — again here referring primarily to cinema, in the case of giant monsters—need some kind of message in the sense of a moral of the story, though this is not something we should rule out. The contemporary distaste for such overtly moralistic art stems from two sources, one legitimate and one illegitimate: legitimately we may detest the simplicity with which overtly didactic productions communicate their message to audiences, treating them as people who need to be told what something is about rather than shown what it is about (a key distinction in any good form of fiction); on the other hand, it is illegitimate to argue that texts ought not to attempt to say anything at all, whether in the name of crass entertainment or “high art,” especially in consequence of the fact that they inevitably have something to say on the unconscious level regardless of the intent of the artist.

In the case of giant monster films, we have texts which emerge from what many have argued is best called the tradition of speculative fiction or SF. SF refers to the meta-genre from which the common sub-genres of science fiction and high fantasy are derived, and is such a kind of “master narrative” in itself constructed by critics attempting to understand what distinguishes this kind of text from the realist forms which dominate the contemporary novel (in its mass market, pulp form, this says nothing of “high literature” which is mostly relegated to academia anyway).

What makes SF so powerful is its inherent capacity (whether or not this capacity is wisely employed is up to the artist) to give us perspective on our social context. We can only derive a fictional world from the rearrangement of elements of our own, and thus the act of creating an SF text involves extracting the stuff of our world and projecting it outwards in a new form. In its better formulations, this results in a subtle shifting of our perspective on our own world, rather than a mere clever production of a new one.

In his book Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction, John Rieder notes that what is interesting in an SF text is not so much its commentary on the specifically speculative material in itself. Discussing Cyrano de Bergerac’s The Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon, argued by some scholars as one of the earliest works of science fiction, he notes that “the main work of Cyrano’s satire is hardly a matter of celestial mechanics…[i]ts crux is the way it mocks, parodies, criticizes, and denaturalizes the cultural norms of his French contemporaries. The importance of his satire has far less to do with Copernicus’s taking the Earth out of the center of the solar system than with Cyrano’s taking his own culture out of the center of the human race, making it no longer definitive of the range of human possibilities.”

Other examples of course abound. One could read Joe Haldeman’s classic work of military science fiction, The Forever War, and look at the time dilation experienced by space marines traveling to other solar systems. For the soldiers, their experience is of 2 years, but when they return to Earth decades have passed. This time dilation becomes even more extreme as the war drags on, and the end result is that the soldiers arrive one day to discover the war has been over for a long, long time, and that ultimately it was a sham to begin with. Though the physics of this story is interesting in and of itself, one risks missing “the forest for the trees” if this is taken to be of interest only in and of itself, with no relationship to the context in which Haldeman wrote. A Vietnam veteran, Haldeman was attempting to write SF that spoke to his and other soldiers’ experience in the Vietnam War, and this text provides a unique perspective on that experience.

What is it about SF that makes it so powerful in this regard? Contemporary author China Mieville has argued that SF’s unique power lies, once again, outside itself as it is a consequence of the mediation of our everyday lives by numerous fantasies. The very economic system upon which our societies are predicated, capitalism, is grounded in the mysterious process by which human labor and nature are combined to produce commodities. These commodities seem to be simple things for use, until we realize that the system is predicated upon a concealed, insubstantial value rather than their actual use, the kind of thing that makes a bushel of wheat and a Blu-Ray of equivalent value: $30. As a consequence of the labor put into the commodity and its relation to other commodities, it takes on another kind of value that determines the way in which the global economy functions. This is what makes bizarre situations like the 2008-09 global financial crisis possible, whereas even imagining this happening from the perspective of people in the distant past seems to be an exercise in SF itself.

Beyond that, however, numerous other fictions govern our lives. The fiction of substantial, fixed gender identity is perhaps the most pervasive and universal fiction governing human culture. Various forms of gender policing, from the obviously gendered toy aisles in department stores, to the horrors of the high school locker room, to the latest cover of a fashion magazine, and so on are testaments to the importance we place on maintaining this fiction. The prevalence of everything from bigoted jokes to hate crimes against transgender persons demonstrate how important this fantasy is to us.

These are just some examples, there are other fictions such as the all-pervasive fiction of racial identity — there is no biological basis for racial identity whatsoever — which results in systematic oppression of entire populations, nationhood (a fiction with a very young history and a disproportionate amount of blood shed for its purposes), and so on. What is important for our purposes is realizing that, in the context of a human civilization governed by fantasies, it makes perfect sense that the act of deliberately imagining a fantastic scenario contains within it the inherent capacity to shed light on the actual fantasies which govern our lives. Thus, for England in 1897, H.G. Wells imagined that Martians could engage in the same kind of colonial assault on London as the British Empire itself had launched on much of the globe, which is simply to say that we never would have had an alien invasion sub-genre without the social practice of colonialism.

With this theoretical foundation now established, let us briefly recount what makes the giant monster sub-genre meaningful in our contemporary world. First off, let us say that there is something to the distinction between the Japanese kaiju eiga and the American “giant monster on the loose films,” at least historically-speaking. Films such as King Kong (1933), The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953), and 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957) represent the latter category. What distinguishes them is the imagery of what is basically a large animal running amok in the contemporary setting, usually unleashed by some act of hubris on the part of humanity pushing into realms which it was meant to remain separate from.

In the end, the same strength and vitality (usually identified with a masculine protagonist) which unleashed the monster is employed to slay it, and so we have Kong shot off the Empire State Building by the most modern of weaponry (airplanes) and the Rhedosaurus killed with a radioactive isotope. These films emerged from the general wave of atomic horror unleashed during the 1950s, itself a rather overt response to the threat of nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union, as well as a response to the bewildering rise of new technologies riding the wave of the post-war economic book in the United States.

These spectacles allowed audiences to experience a certain catharsis, relieving the tension of the contemporary standoff between the superpowers that haunted so many who feared a return to the great world war that they had only so recently escaped. The vastness of this new world of massive architecture, global wars, trans-oceanic trade, and so on could be projected onto the image of a living giant, something more immediately approachable, understandable, and indeed killable than reality itself.

In this context, it is no surprise that such imagery would resonate in Japan, which experienced these transformative processes in a much more condensed fashion than other world powers. Japan had experienced a self-imposed isolation from the developments of world colonialism as late as the 1850s, and only after having its trade relations imposed from the outside did it seek to become one of the great powers itself. The Meiji Restoration was actually a revolution from above imposed by Japan’s ruling class on the entire country, a revolution in relations of production and consequently in social relations generally speaking.

Through incentives and more direct means, farmers were compelled to leave behind their rural way of life (or at least their children were) to head to the cities in order to work for wages (itself a strange fantasy which we take for granted today). Their entire world was upended, but nonetheless the cult of the Emperor held the cultural fabric of the country together…until the vast and terrible Second World War upended the entire arrangement, demystified the Emperor’s divine status, and resulted in the wholesale destruction of the country at the hands of a merciless bombing campaign, which culminated in the horrifying use of atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

This sense of being rapidly thrown into a new world is at the core of the estrangement produced by the SF elements of the kaiju genre. At first, producer Tomoyuki Tanaka sought to produce something rather like the American giant monster films. Early treatments of Gojira even featured the iconic attack on the lighthouse scene, which was the original inspiration for The Beastitself as found in Ray Bradbury’s short story “Fog Horn.” Nonetheless, the trajectory of films running from Gojira (1954) to Mothra (1961) represents the birth of an entirely new genre which combines elements of capitalist modernity with Japanese notions of kami and yokai, producing the “strange beasts,” or kaiju, that we have come to adore.

What distinguishes these entities from the American run of giant monsters is their very nature. Though they retain morphological characteristics of animals both living and extinct, the kaiju are at their essence something more like forces of nature. In the pre-capitalist Japanese cultural systems, kami were personified forms of underlying animistic spiritual realities. Spanning everything from rock spirits to ancient ancestors, kami and their various lesser spirit cousins are broadly representative of a worldview which saw a radical continuity between the seen and unseen worlds of the natural order. A similar aspect of this cultural sensibility can be found in the notion of yokai, trickster and other spirits of a much more banal form. Indeed, much of Japanese horror is grounded in this unique sense of the utterly bizarre and grotesque as a founding principle of hauntings and visitations.

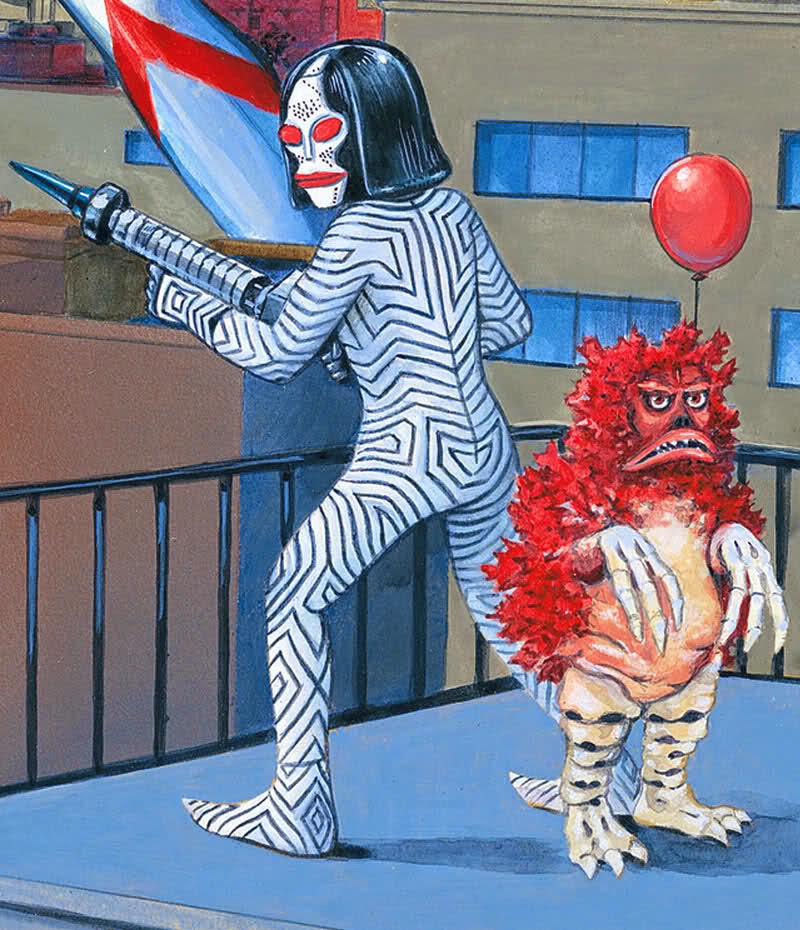

Kaiju in many ways represent a blending of these two sensibilities, producing entities which simultaneously serve as unrecognizable forces of the grotesque and absurd (yokai) as well as sublime forms of the structure of nature itself (kami). Wedding together this ghoulish and divine sensibility into one entity, we get such mythopoetic beings as Varan who awakens from his slumber to exact vengeance on literal transgressions of sacred land, Mothra who serves as a nature goddess complete with a pair of fairies, or Baragon who terrorizes farmers by rising from the Earth — that perennial symbol of the return of the repressed — to devour unsuspecting livestock. The appearance of kaiju itself sets them off from Western creations which are usually directly modeled on animals, or at their best contemporary versions of Greek mythology. By contrast, one can see the interpretive, anti-naturalistic sensibility of Japanese art in the faces of such bizarre creatures as Gabara, Dada in Ultraman, or Garamon from Ultra Q.

The genre came into its own with Mothra (1961), arguably the first distinctly kaiju film devoid of significant allusions to the American films. The golden age culminated in the mid-1960s “monster boom,” which saw multiple studios attempt to copy Toho’s success with such films as Daiei’s Gamera (1965), The X From Outer Space (1967), and Gappa (1967). The collapsing Japanese film industry led to a shift towards children audiences, but in many ways this represents a natural progression for the genre. Serious themes were still explored in the late 1960s and 1970s, but the movement of kaiju to children stories plays into the fairy tale-esque nature of enmonstered role models for children. To this day children identify with Ultraman the monster slayer and Godzilla the defender of Earth, connecting the mythopoetic elements to their original source material in pre-capitalist Japanese culture itself.

Nonetheless, the real apogee of the genre itself is to be found in Ultra Q (1966), which some have described as X-Files meets Godzilla. Inspired by the groundbreaking SF shows The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, Ultra Q really put the strange back into the strange creatures. The series variously put on the mantle of horror, humor, science fictional thriller, and out and out fantasy in order to convey the weirdness of contemporary life by way of the kaiju. Whether the kaiju were indeed giant monsters or more modest creatures of humanoid dimensions, the series explored the essence of kaiju as warnings, instructions, and symbols of a world “out of balance” with the natural rhythms of the Earth. Coming on the heels of Japan’s great capitalist recovery from World War II’s devastation, the series captured the estrangement of society and the great chasms opened between the old world and the new by the march of a highly industrial modernity.

Much can be said about the 1970s Godzilla films and the Gamera series, but it is important to note that the decline of the genre coincided with the normalization of Japan’s new capitalist social order. Anime, super sentai, and so on eclipsed kaiju for a variety of reasons, but one cannot deny that there is at least some correlation between the consolidation of the post-war order and an end to a fascination with strange hybrid beasts born of modernity and Japan’s ancient past.

Now we see a kind of neo-kaiju genre emerging in the United States, but only time will tell where this new sensibility is going. Serving as an homage and an update at the same time, the films Cloverfield (2008), Pacific Rim (2013), and Godzilla (2014) coupled with planned productions of a Pacific Rim anime series and a SyFy original series called Creature at Bay altogether represent a blending of these Japanese elements with a decidedly American sensibility. In each of these films, a sense of estrangement and strangeness, as well as utter helplessness is rather evident. Kaiju are compared to hurricanes and forces of nature, which must be respected and approached with a transformed perspective. In Pacific Rim, the story tells us of how humanity created monsters of their own to fight monsters, a poignant image of the dialectic of technological advancements and natural forces.

Nonetheless, the power and uniqueness of that original moment running roughly from 1954 through the late 1960s is unlikely to be replicated. The golden age of kaiju was a cultural form resonant with a period of utter psycho-social crisis brought on by an uncharacteristically rapid form of capitalist development, an uncharacteristically devastating inter-imperialist war, and an uncharacteristically rapid industrial recovery.

The blending of kami and yokai with American atomic horror resonated with Japan’s own hybrid cultural forms, born of an adherence to patriarchal and agrarian traditions alongside rapid modernization at the hands of a state allied to the most dynamic and powerful imperialist power the world had seen up to that point. The strangeness of the creatures is only rivaled by their vastness, itself a testimony to the sense of collective vertigo experienced by an agrarian society rapidly transformed into a highly urbanized one.

In sum, giant monsters generally, and kaiju specifically, are symbols which resonate with a uniquely global capitalist culture. They are the products of globalization, imperialism, hybridization of cultural forms, new forms of mass media, and so on. They serve as monstrous symbols uniquely tailored to a world bewildered by rapid industrialization, total war, and a vast expansion of the scale of commerce and development compared with human civilization’s more humble agrarian origins.

These unique fantasies are likely here to stay, albeit in new forms as the old suits give way to CGI. Nonetheless, just as the suits and masks recalled the Japanese Noh plays (in which the last act featured a man in a demon mask doing a dance of death, not unlike the destruction of Tokyo by a rubber-suited man in the last act of Gojira), so too does today’s CGI creations recall our own particular cultural imagery, such as “the Wave” in Godzilla (2014) and the Japanese tsunami of 2011. Detractors may decry the lack of suit work for the new American productions, but they have taken an enormous amount of inspiration from Japanese source material and represent rich visual storytelling on a scale rarely seen in today’s shallow Hollywood action films. Let us hope that a kaiju renaissance has only now just begun.

Jase Short is a writer and activist from middle Tennessee. He studies philosophy, science fiction, and politics and maintains a blog called The Ansible.