As a youngster growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, Emory Douglas was always in and out of youth detention centers. The counselors knew him and knew that he liked to draw. Douglas’s mother ran a state-run concession stand for the disabled at one of these and knew a lot of the probation officers to whom she would talk about Douglas’s talents. [1] Douglas was raised by his mother, who was legally blind and worked hard as a single parent. Downstairs from Douglas lived an artist named Charles Bible who would mass-produce multiple paintings of the same image of Malcolm X every year for anniversary celebrations of Malcolm X’s life. Through talking to Bible, Douglas learned about Bible’s assembly-line production process as well as Bible’s painting technique. This information became very helpful to Douglas when he began doing portrait paintings over the years. Growing up Douglas found artistic influence from the work Charles White whose art Douglas had seen on a calendar as a child at his aunt’s house. [2] While Douglas was in the Youth Authority system, he worked in the print shop at the Youth Training Center. They asked Douglas to design the logo they would use to label materials to be shipped out. This was essentially Douglas’s first commission. [1]

In the youth detention center Douglas worked on mostly landscape art, without social meaning. A year or so after his release, Douglas decided to attend the City College of San Francisco. The counselor at the detention center heard about Douglas’ plan and suggested that he take up art. When Douglas enrolled, a college counselor suggested Douglas major in Commercial Arts. After this, Douglas’ whole idea of going to school became to break into the commercial art field. He developed his graphic design skills to a professional level, and was sent out on various job assignments. He worked at a silk-screen factory where he learned the silk-screen printing process. He also worked a fine wine goblet and silverware store in downtown San Francisco doing layouts as well as cutting and pasting advertisements and preparing signs for store window displays. He attended City College off and on from around 1964 to 1966. City College introduced him to basic graphic design elements such as figure drawing, sketching, illustration drawing, lettering, layout and design, pre-press production, the offset printing process, and the basic animation process. This educational practice also taught Douglas how to critique and evaluate his own work. City College was Douglas’ only academic graphic design training prior to actual on-the-job training.

Douglas attended college at the height of the Civil Rights movement. At this time, commercial art firms were not hiring African-Americans. While attending City College there was only Douglas and sometimes one other black person enrolled in Commercial Art classes and about 20 students per class. During this time there were graphic styles Douglas created which one instructor told him was not commercial enough. After creating a magazine layout similar to EBONY magazine another teacher told Douglas that he had appreciated what Douglas had done, but that it would take another 10 years or so before ideas like Douglas’s would be accepted.[2]

At City College Douglas and other African Americans had begun to define themselves. They went from being called Negros to being called Black or African American. San Francisco (SF) State had one of the first Black Student Unions (BSU) in the country. Douglas and other black students from City College would go out to the San Francisco State BSU because of the political and cultural activity going on there. The SF State BSU had many speakers come through such as Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, and Sonia Sanchez. When Amiri Baraka was invited by SF States’s Black Studies Dept. to produces theater performances, Douglas asked him if he could create props and backdrops for his plays, and Baraka agreed. During this time, there were student community activists at State who were planning an event to bring Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Shabazz, to the Bay Area. Having known his graphic skills in the Black Arts Movement, these students wanted Douglas to come to a meeting for the event because they wanted him to to do the poster. While at the meeting there was talk about some guys coming over to do security. Douglas did not know these men at the time but they turned out to be none other than Huey Newton and Bobby Seale from the Black Panther Party (BPP). Dressed in leather jackets, blues shirts, berets and black slacks, Newton and Seale were armed when they came to meeting. Fully understanding the gun laws of the time, Newton and Seale appeared ready to defend themselves. It was right after this meeting that Douglas asked how he could join the party.

The first official thing Douglas was asked to work on for the BPP was the Black Panthernewspaper, but he was also asked to redraw the Panther symbol. The Panther symbol the party was using at the time that was big and fat. The BPP wanted to make the Panther symbol smaller to reflect that the party was about serving the underserved and and undernourished. They did not want the panther to look well fed and healthy. The symbol of the Black Panther evolved from a varsity sports team logo in Lowndes County, Alabama. In Lowndes Couty there were extreme conservative right-wing politics and white racists and there was a high illiteracy rate among Whites as well as among African Americans. White racists were able to go to court to get a symbol of a rooster put on the ballot so illiterate whites would know how to vote for the racist party without even being able to read or write. This opened the door for black people to do the same thing. African Americans chose the high school sports mascot of the Black Panther as the symbol to use at the ballot box. [1]

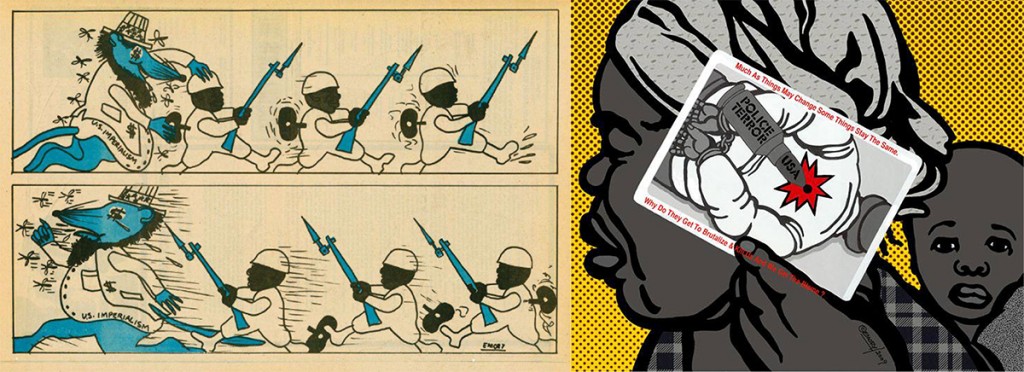

U.S. Imperialism (Left), Police Terror USA (Right)

All across the country there was there was high levels of frustration of black youth in this country do to police violence, brutality, and murder of people in the black community.Throughout being in the BPP Douglas worked on the BPP newspaper. He started by cutting and pasting the layouts for the newspaper but by the third or fourth issue Douglas became in charge of the newspaper, creating artwork and design which he had learned at the city college. Shortly after Douglas was appointed the Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party. Douglas’ artwork allowed the community to learn through observation and participation. [3] Graphic art was crucial for communicating the BPP’s message since there were so many illiterate people at this time. [1] As opposed to reading a long article, Douglas’ artwork helped people get the gist of what was being discussed in the newspaper articles through telling stories with his images. [3] Douglas formatted the paper in a way that was more visual with simpler captions and headlines above the paper so that people could understand the message without necessarily reading the long articles. Douglas tried to make the artwork broad enough so that even children could understand it. [1]

Some styles of artwork that Douglas knew he had learned at city college but these were not considered commercial styles. Douglas knew in order to get a job in the capitalist art market he had to learn a more commercial process of art production to build a portfolio to get a job. However, when Douglas began getting more involved with activism and the BPP he began going back to his roots artistically and was able to use his more noncommercial art styles for the use of the Party. His drawing style developed off the aesthetic of woodcuts. Douglas said that he liked woodcuts but the process took too long to do so he developed a style of drawing similar to the aesthetic of woodcuts with brushes, pen and ink, and markers. [3] Politically, Douglas’ art was inspired by the politics and artwork that was being created at the time, particularly the of the Cuban poster artists of OSPAAL (Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America). He also found influence from the political artwork from China, Vietnam, Palestine, and the Anti-War movement. [2]

Around six o’clock in the morning comrades from the BPP would go out to sell newspapers. They had to be at their selling spots at 7am so along the way comrades would use flour and water to wheat paste old newspaper posters and issues. This really began to define the community as a gallery for art. Working people just trying to get by in the system, who could not afford to go to an ivory tower gallery, could now see these images on their way to work. Workers could see themselves in these images and feel empowered. [1]

What is a Pig? (Left), It’s All The Same (Right)

Douglas’s role as Minister of Culture for the BPP involved communicating the party’s message to a community with little experience of formal politics. His drawings and images in the Black Panther newspaper illustrated empowered black people as well as representations of their oppressors, the Pigs. The Pigs stood for everyone from the local police to the president. [4] Bobby Seale and Huey Newton would call police pigs and swine because of the nature of pigs being depicted as fat, sloppy, and wallowing their filth. This idea of pigs being nasty and low natured things translated well into the idea of police as pigs given the nasty way police terrorize the Black community both then and now. Newton and Seale first asked Douglas to draw a pig for the front of the newspaper. There was a cop named Frey who was notorious for harassing people in the community. When Douglas drew Frey as a pig, he included Frey’s badge number in the drawing. He continued this idea by publishing other police badge numbers on his pig illustrations on a ongoing basis. This worked to warn the community of these bad cops but also to expose the police and let them know that people were watching them. After this, Douglas’s pig character took on a life of its own. He began to draw from his commercial art experience of critiquing his own work and decided to start illustrating his pigs differently. The pigs still displayed actual officer badge numbers but now they wore pants and were standing up on two hooves with flies flying around them. These anthropomorphic pig illustrations became the iconic figure of “The Pig” still used in anti-police and revolutionary rhetoric, music, and art today.

At the height of the paper the BPP was printing about 100,000 papers or more weekly, each being read by three or four individuals on average so they had a readership of 400,000. The papers were distributed to Harlem, all the different chapters on the East Coast, and all over the South. Also, the paper had teachers and labor unions who would pick up bundles as well as libraries and churches. Then there was also international distribution from the anti-war dissidents in Canada, Europe, Scandinavia to the Chinese, Korean, and Cuban governments requesting the paper. All the while the American government was using any means necessary to destroy the newspaper. They would wet them in transit to make them unreadable, delay distribution, and put pressure on the paper. The US government recognized that The Black Panther newspaper was a powerful tool for educating, informing and enlightening the people and saw it as a threat to the authority of the ruling class. COINTELPRO (the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program) was even researching a way to put a feces smell on the newspaper so that when people would read it the paper would reek of feces. [1]

The purpose of the BPP newspaper was to tell their own story of struggle outside of the distorted mainstream press about events, concerns, as well as stories of struggle from solidarity groups all over the world. The corporate media distortedly depicted the BPP as hoodlums and thugs whose only concern was violence and guns. This was far from the truth. Not everyone in the BPP even carried guns, only those in the party who were assigned to. The BPP also carried guns in accordance to the laws and constitution at that time in order to protect their homes, property, and community from the predators of the US government. The BPP were not “thugs” or “outlaws” as often depicted. They were a party dedicated to revolution with many social programs such as health clinics and breakfast programs.

The party was able to expose an educate people to what the government was not doing in regards to the breakfast program. The BPP was feeding more hungry children than the US government. The BPP was also concerned with educating and providing preventative healthcare to people as well as free health clinics available staffed with accredited professional doctors and nurses. Also the BPP set up free bus to prisons programs which would help transport families and friends to visit their loved one who were incarcerated. The success of the BPP is that it lasted as long as it did in the belly of the beast [3].

Though he continued to produce art, up until 2007 Douglas had worked for two decades as the pre-press manager for his local newspaper, the Sun Reporter. In 2007 with the publication a large-format art book and an accompanying retrospective at MOCA in Los Angeles, Douglas began to receive the attention from the art world that he deserves. [4] Even at his age of 71, Douglas continues to create politically charged revolutionary art. In late 2012, Douglas met with the Zapatistas and local artists in the Mexican state of Chiapas in an artist residency initiated by Caleb Duarte from EDELO (En Donde Era La ONU). During this residency, Douglas along with local artists from Chiapas created and art exhibition as well as the Zapantera Negra which was a single-run magazine of 20,000 full-color copies that merged the powerful imagery and layout style of Emory Douglas with the visions and voices of the Zapatista painters and embroidery collectives. [5]

Douglas believes that art has to expose the issues that concern human beings and people who are being oppressed. Art must be able to communicate with people and be a reflection of their desires and concerns in order to be relevant in relationship to change. [3] As artists and revolutionaries, we have a lot we can learn from Emory Douglas about art, politics, and communication, in the continuous struggle for human liberation.

Works cited

- Roberts, Shaun, and Emory Douglas. “Emory Douglas.” Juxtapoz Mar. 2011: 40-57. Print.

- Daniel, Jon. “Four Corners – an Interview with Emory Douglas.” Graphics, Digital, Interior, Print, Retail, Design News & Jobs. Design Week, 21 July 2014. Web. 18 Sept. 2014.

- “Emory Douglas: The Black Panther Party and Revolutionary Art.” YouTube. Angola 3 News, 9 Nov. 2009. Web. 18 Sept. 2014.

- Rayner, Alex, and Emory Douglas. “Fight the Power: Alex Rayner Meets the Former Black Panthers’ Minister of Culture.” The Guardian: Art & Design. The Guardian, 24 Oct. 2008. Web. 18 Sept. 2014.

- Duarte, Caleb. “The Black Panthers and the Zapatistas: An Encounter.” Kickstarter. EDELO, 17 Oct. 2012. Web. 18 Sept. 2014.

Craig E. Ross is an artist and radical living in Carbondale, Illinois. He is an editor at Red Wedge.