"Art is not a matter of rare, occasional masterpieces.” — Holger Cahill, National Director of the Federal Art Project

A giant sloth rises up on its hind legs, welcoming us into an exhibition of New Deal artwork. The prehistoric creature’s large walnut tongue licks at the air, signaling we are in store for a unique display of materials. Around the corner, we encounter a glazed hippopotamus that is stylistically reminiscent of its ancient Egyptian ceramic cousins so popular among funerary objects. The curvaceous sculpture is displayed next to a delicately rendered and wonderfully bawdy print by Vincent Glinsky entitled Municipal Bathers. Unlikely subjects and uncommon pairings occur everywhere, and are enhanced with contemporary photographs and paintings made specifically for the exhibition. So, what is the significance of a museum show of ceramic hippos, wooden dinosaurs, architectural models, portraits of children, and landscapes of urban winters or prairie tornadoes?

New Deal Art Now: Reframing the Artifacts of Diversity is an exhibition of creative works by artists and laborers of the New Deal that redresses the inaccurate framing of New Deal art as stylistically or representationally limited. It offers a sampling of the breadth of the Works Progress Administration and Federal Art Projects (WPA/FAP), calling attention to the skills, histories, and social identities of an extraordinarily diverse spectrum of professional and amateur artists funded by the United States federal government during the Great Depression.

Left: William S. Schwartz, Symphonic Forms #40, 1940. Right: Fred E. Meyers, Giant Sloth, 1939-1941

With the failure of the US stock market in the fall of 1929, Americans found themselves caught in the rapids of an economic collapse that quickly rippled into virtually every aspect of daily life, and also had disastrous effects on many other communities throughout the world. In the United States, thousands of banks and businesses closed, millions of people became jobless, farms foreclosed, and many people were literally starving in the face of homelessness and food shortages. Agricultural workers, factory workers, homemakers, longshoremen, teachers, and artists alike all found themselves in this landscape of despair that is today known as the Great Depression. Different classes, genders, and ethnicities did not struggle at the same level, and it was the working classes whose living standards fell the quickest, while the poor sunk to utter destitution, putting their lives at risk. It was this crisis that motivated a major portion of the impoverished masses to demand relief from their governments, at both state and federal levels. Unions, which had existed well before this, but had been decreasing significantly since the previous decade, had a new resurgence due to the overwhelming needs of Americans and their desire for substantive change. The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 guaranteed workers the right to collective bargaining. In the same year, in New York City, the Unemployed Artists Group began demanding assurances of employment for artists, and by 1934 had renamed themselves the Artists Union, due largely to their success in gaining work in their field.[1]

Local public outcry impelled a federal response. The result was that many Americans in the 1930s and 40s ended up benefiting both directly and indirectly from federal economic stimulus and relief initiatives known broadly as the New Deal. The programs, a massive expansion of earlier, less successful relief projects under President Herbert Hoover, were launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the start of his first term. He believed that government could assist Americans not only through employment, but could also uplift a people suffering in the Great Depression through cultural enrichment. The intention within the administration was to expose all classes of Americans and their families to art, effectively developing a culture of art in the US on a mass scale.

In order to accomplish this, the initiative included the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal One Projects. Running from 1935 to 1943,this was a program within the New Deal that employed artists and artisans in creative production and education. Citizens in hundreds of rural communities and cities were beneficiaries of funding for projects that included the Federal Art Project (FAP), Federal Music Project (FMP), Federal Theater Project (FTP), Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), as well as the shorter-lived Historical Records Survey (HRS). Additionally, under the immediate supervision of the WPA was the highly productive Museum Extension Project (MEP), a cultural development program directed to “help public schools to obtain visual education aids designed to give life and reality to the things children study.”[2]

Holger Cahill, the national director of the specific Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA/FAP), had a four-phase plan in order to accomplish unification of the American community with artists. This involved: establishing community art centers throughout the country, creating an art lending program for tax-subsidized institutions, showcasing funded art through traveling exhibitions, and writing the Index of American Design – a survey of vernacular American decorative arts in the United States.[3] Cahill identified the basic aims of the program:

The plan of the Federal Art Project provides for the employment of artists in varied enterprises. Through employment of creative artists it is hoped to secure for the public outstanding examples of contemporary American art; through art teaching and recreational art activities to create a broader national art consciousness and work out constructive ways of using leisure time; through services in applied art to aid various campaigns of social value; and through research projects to clarify the native background in the arts. The aim of the project will be to work toward an integration of the arts with the daily life of the community, and an integration of the fine arts and practical arts.[4]

Left: Picketing artists. Source: Francis V. O’Connor, New Deal Art Projects (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972), 217. Right: Alley exhibition. Source: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian, Washington D.C

The FAP and all of these various projects within the WPA provided economic support and cultural enrichment to millions of Americans in the form of jobs, entertainment, and education in the arts. They remain today the largest government sponsorship of cultural production in the history of the United States. Employing thousands of workers in any given year, 5,300 people in the WPA alone were being paid for their labor at the height of its effect.[5]As a result of the New Deal programs’ scope, a diverse tapestry of amateur and professional workers laboring across many classes and styles formed what is today a de facto archive of Depression Era cultural work that resists easy categorization.

In the exhibition New Deal Art Now, a wider range of works is shown than is typical of many Works Progress Administration-themed shows. Artworks by trained and untrained artists, women, immigrants, minorities, and in some cases anonymous individuals, alongside works by well-known artists, illustrate the programs’ ambitious scope. Painting, sculpture, educational models, archival film, audio, and photography are juxtaposed alongside contemporary artworks created in response to the exhibition. By situating these works (as well as the very categories of amateur and professional, art and artifact, museum and archive, past and present) in productive relation to one another, the exhibition argues for the significance of all of these works and artists to the diverse history of twentieth-century American art.

Because of the exhibition’s broader framing of these artworks, viewers also enjoy a greater degree of range and complexity across the pieces with which to engage in dialog and ask questions such as: What defines something as art? How is value determined?

Fred Myers’ Giant Sloth (Fig. 2), the unofficial show mascot, is a useful example to illustrate this point. Using WPA funds, rather than Federal Art Project money, Southern Illinois Normal University Museum contracted him to carve one wooden educational display a month for a project that was directed at the rehabilitation and expansion of the museum. Using reclaimed walnut stumps that a friend salvaged for him from a local Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) project, Myers worked hard to produce sculptures that he was satisfied with. He often expressed frustration with the time constraints imposed upon him, demonstrating his sense of self-worth as an artist. While Giant Slothwas never commissioned as a work of art in the traditional sense, it has aspects that are sought for in the evaluation of a work as art. It possesses quality of both material and artist’s skill along with a strong composition. At what point did it become art, and who decided this? Art historians and authors Richard A. Lawson and George J. Mavigliano celebrate Myers’ artistry and discuss the marginalization he experienced as an artist within the prevailing tastes of the time. In response to their question “what is it then that makes Myers’ carvings art?” they suggest that it is the “act of doing rather than the result” or specifically the action of making art that made it art.[6] I would assert that it is also the viewer that gives value to a work. When one engages or even disengages with a work, one automatically ascribes some value to it through interaction. Visitors of all ages have been drawn to Myers’ Giant Sloth, delighting in its expressive body and finish. The artwork is so appealing in fact, that the piece is ensconced in a vitrine to prevent curious hands from adding to its patina. The enclosure of this figure, not unlike bullet-proof shields around venerated modern celebrities, thus further signifies the sculpture as a rare object worthy of admiration, and through this action, galvanizes the museum’s position as an arbiter of value.

To further engage in any of these questions on valuing within the framework of New Deal creative production, the history of the WPA moment should be weighed against general assumptions. For example, while the art produced under the aegis of the WPA is casually and often associated with the style of Social Realism by novice historians, a wide variety of identities and artistic genres and styles actually flourished in many of the federal programs of the New Deal. Known for subject matter that reflects hardship, inequity, and the conditions of everyday working-class people, Social Realist art is predominantly figural and stylistically representational. However, there is a significant amount of New Deal art that is not socially subjective and/or representational, thus proving by their sheer existence that the work should not be reduced to wholesale generalizations.

Incomplete or generalized understandings of the federal projects’ works are partially the result of cumulative curatorial choices made over time by institutions, and the limits of general public accessibility to the materials in those institutions. Due to the breadth of the subject of New Deal art, curators and institutions necessarily limit the extent of their exhibitions, thereby inadvertently condensing the extraordinary scope of the projects, and perpetuating misunderstanding. Scholars have also been responsible for perpetuating a narrow image of the work. WPA/FAP art has many times been contextualized under themes or styles that are limiting to the point of eliding the otherwise complex histories of the period.

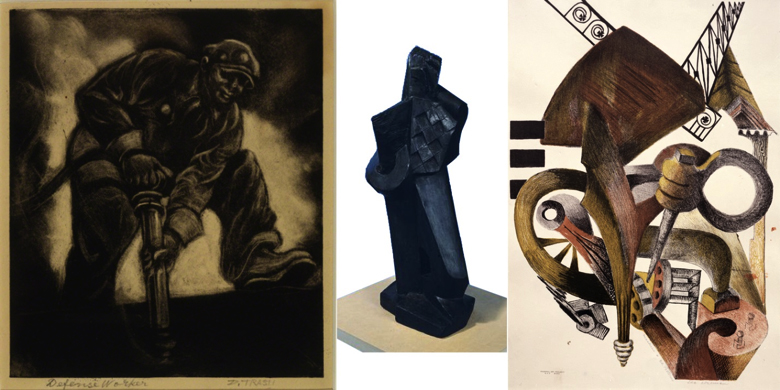

Even though subject themes such as “American Scene” (Grant Wood’s pre-WPA American Gothic is a foundational stylistic example) were systematically encouraged in the early years of the programs, artists still experienced a high degree of license in both style and medium. For example, the idiosyncratic artist Gertrude Abercrombie (Fig. 6) forged a successful career by synthesizing her unique painting approach with magical realism. Derived from her own personal mythos, reoccurring insertions of objects that were significant only to her, such as houses, hills, gloves, hats, and an empty sofa, paired with moody palettes, interwove to form magical realist expressions that are both inviting and uncanny. Crediting the New Deal programs with enabling her to become a professional artist through the financial support of $94 a month, Abercrombie had the space to develop her creative style during the federal funding of the arts, subsequently flourishing as a painter after the Great Depression ended.[7] The printmaker and painter Dox Thrash also took advantage of the flexibility and experimentation enabled through the WPA/FAP, and co-invented the carborundum print-process while working in the Philadelphia graphic division. Including Thrash’s carborundum process, there were many technical innovations within the graphic division, such as perfection of color lithography and silkscreen.[8] Thrash’s “carbographs” or “Opheliagraphs” (named after his mother) allow excellent tonal range and expressiveness of hue, and is a process still in use today.

Left: Unknown Artist, Model, Jackson Co. Jail at Brownsville, 1939-1941. Right: Mickey Everett, Untitled/Gertrude Abercrombie’s Lonely House, 2014

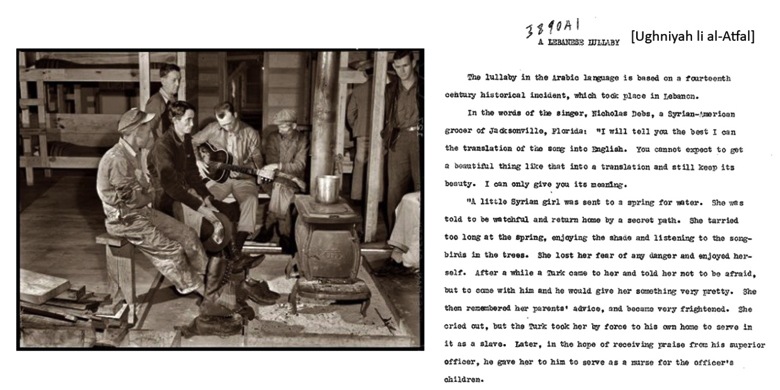

In addition to stylistic diversity, there was also ethnic and gender diversity in the various WPA art-based programs, when compared to the field of art in previous decades. Among this diversity of identity, there is a noticeable representation of subject matter specific to the artists and their communities. This approach to content was directly promoted by administrators of the programs, yet was also customized according to audience and communities served. For example, under Hallie Flanigan’s direction, the FAP quickly developed ethnic and language-based units such as the African American Negro Theater Project (NTP), and units that performed in Italian, Spanish, Yiddish, French, and German. While having a problematic relationship to race politics and ideologies of the time, these units acknowledged the value of diverse productions that could employ thousands of minorities, while offering critical or even overtly political content. In addition, the FAP and the FWP featured the work of minority communities, as in the case of the Florida Folklife Project of the FWP which documented numerous Bahamian, Seminole, Czeck, Conch, Greek, Italian, African, Syrian, and other traditions of musical and vocal expression. Popular FAP exhibitions of Native American and Hispano American artwork showcased the Southwest and toured the country. At a time when difference in American culture had not yet been well supported by the government, the New Deal programs made considerable progress on this front. In many ways, ethnic diversity in the arts became a form of cultural capital that was promoted by the government. And, while this new directive led to the potential exoticization or “othering” of ethnic groups, it is useful to also acknowledge the degree of increased agency and equity within the arts that it created.

The diversity and the homogeneity, the marginalization and the inclusion, are important to address if we are to attempt a weighed understanding of what “diversity” looked like at the time, and where we stand now. In conjunction with both the advocacy and struggles of women and minorities, many of the creative programs of the New Deal advanced ethnic and gender diversity in the United States. African American representation in Federal One owes much to the artists and activists of the Harlem Renaissance and Chicago in the 20s who forged their own programs and visions before the Great Depression arrived. Additionally, the suffrage movement, which enabled women’s participation in politics, laid the groundwork for their advancement as professionals in high-level administrative positions in the WPA. This ultimately led to the broader promotion of women by women for professional jobs and pay. Because of this important period in which women and minorities were gaining better representation (yet were still proportionately underrepresented), today’s archives and publicly-sited projects operate as repositories of histories that are not fully claimed. The works function as documents of the period. If they are read and valued for their distinctness and their contribution to a historical moment, a more complete picture of the New Deal is revealed.

Left: Photo of men playing music in a bunkhouse, 1940. Source: Florida Folklife from the WPA Collections. Right: Partial transcript of Lebanese Lullaby, recounted and performed for the Florida Folklife Project by Nicolas Debs

The content of artworks produced in the FAP varied considerably. Subject matter might have included idyllic pastoral representations of rural life or related material influenced by American Regionalism. Other artists represented the experience of city life in all its glory and horror. Examples of these geographic influences include Selma Day’s playfully abstracted cow and corn motifs in Mural Panel, or Bernice Berkman’s vibrant South Chicago No. 2,which depicts the frenetic energy of street life as a concert of color and movement.Many other artists portrayed the struggle of the individual during the depression, especially as it related to marginalization and labor issues. However, works like Catherine O’Brien’s Children’s Recreation (Fig. 9)depict youth in an expression of hope and carefree life. In her painting, an elongated landscape pops with cheerfully abstracted fields of pastel that capture the geometric space of playgrounds, parks, gardens, and even a zoo. Energetic youth playing games engage the viewer’s eye, causing them to lose themselves in the scene, pulled in by a childlike imagination.

Under the leadership of Holger Cahill, FAP artists enjoyed stylistic flexibility, which ran the gamut from figuration to abstraction. “There was always a feeling of total freedom, and we were permitted to produce whatever we wanted,” said artist Donald Vogel of the Illinois Art Project (IAP). “My own work was most personal and never gave way to existing trends…”[9] Although belying a nationalist perspective and a preference for two-dimensional works, Cahill’s dictum that “anything painted by an American artist is American art” illustrates his belief that all styles were valid.[10] A wonderfully vibrant and abstract painting by the Russian immigrant William S. Schwartz titledSymphonic Forms #40 (Fig. 1) is part of a series of sixty-six abstract paintings referencing music that were begun by him as early as 1924. It is commonly understood that his musical career, which paid for his education at the Art Institute of Chicago, informed his series, a study of the form or representation of music in abstract shapes. #40 is formally rich, comprised of warm, aggressive hues of orange and red that formally move around the canvas in a cyclical and haunting mass. Another stylistically unique artist, the Hispano American sculptor Patrocinio Barela had been carving wood saints before the WPA started. When he joined the program he was encouraged to not only continue this subject matter, but also to continue his own unique style. His commitment to it earned him not only national praise but the problematic descriptors “true primitive” and “modern primitive.” Barela’s Bulto (#4-B)illustrates both his connection to and use of a tradition, along with a partial departure from that tradition through his shaping of bold, dynamic forms, and in leaving the pieces unpainted.

In addition to the flexibility allowed in the FAP, there was also a wide range in genres and styles within the FMP, the FWP, and the FTP. Written work ranged from fictional and non-fiction prose to poetry, and included criticism and documentary surveys of song and experience. This variety in itself was celebrated during the WPA by authors and guilds around the country.[11] Musicians of the FMP found room for a diversity of genres, and enjoyed stylistic freedom that ranged from National Folk Festivals to venues for contemporary music performances. A broad scope of genres was generally more the case in a major city like New York where the New York Composer’s Forum, a project of the WPA, sponsored public performances of compositions by renowned avant-garde artists such as Henry Cowell and the less-known but equally remarkable percussion and electronic pioneer Johanna Beyer. It is thanks to notes from the FMP’s Composer’s Forum that the history of her short life (due to ALS) and vibrant production are documented and available today.

Catherine O’Brien, Children’s Recreation, 1940

All told, nearly 200,000 artworks were produced in the WPA/FAP.[12] Interestingly, this figure does not take into account all of the applied art, graphics, and posters produced within all of the various FAP sections. For example, the amount for these items in the Illinois Art Project alone is 750,362.[13] Also not included in this figure is the total of all creative works produced in every WPA program, nor the work produced in two other New Deal art programs, the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and the Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture (later known as the Section). The PWAP and the Section are not covered in this iteration of the essay due to considerations of length. However, it is important to emphasize that these two programs were more stylistically restrictive and traditional in outlook, especially the PWAP, and they both served the main purpose of adorning federal buildings with murals, predominantly in the representational “American Scene” tradition. Less than 18,000 murals and relief sculptures were made in these two non-WPA Treasury Department direct-sponsored programs of the New Deal.[14] When we consider then how much work was produced in the entirety of the WPA, it is remarkable that the more traditional PWAP and Section characteristics have somehow been mapped onto WPA work. In the WPA, there was a considerable range of subjects and styles within sculpture, painting, writing, music, and theater. However, it is the mural art featuring historical subject matter, and the posters celebrating labor and community,that are what the WPA is often remembered for today. Perhaps this is because less of the WPA work is known to the public for various reasons: much of it was contained in archives, lost, privately owned, given to government employees, or even destroyed in the liquidation process at the close of the programs.

Legacy

The WPA is one of the most significant federal relief projects in American history for its impact on 20th century public society. Arriving at a time when a uniquely American brand of culture was being called for, the expansive and idealistic Federal One programs filled a gap created by divestment from European culture. The multitude of creative outlets for artists and patrons, along with considerable infrastructural support for public land, parks and buildings, coming from programs like the CCC, encouraged the development of a middlebrow American culture through the promotion of art as a consumable good. However, to enjoy art one must not only be exposed to it but must develop a discerning appreciation for it. Art centers were particularly focused on cultivating art appreciation through classes on style and genres. With millions of visitors enjoying the centers’ programs, the New Deal directive of culturing the middle-class public was well met.[15] John Dana, Director of the Newark Museum, and mentor to Holger Cahill, was one of the early proponents of the view that the role of the museum in educating the public superseded the role of conservation.[16] In addition to Dana, other curators and art critics of the time also promoted the idea that commonplace design and everyday cultural traditions could and should take their places in the museum over fine art.[17] This way of thinking directly echoed the view of Holger Cahill, who poignantly said, “Art is not a matter of rare, occasional masterpieces.”[18]

The sheer diversity and quantity of cultural production during the WPA period effected a rapid development of art appreciation among Americans that lasted for decades, and was most notable in 1950s and 60s consumer culture. For example, the American Guide Series of the Federal Writer’s Project was a collection of promotional materials designed to highlight the best features of a state, city, or region, thereby encouraging its readers to enjoy the natural and cultural wonders of an area by “Seeing America.” People who could not travel to more distant locations, perhaps because they did not yet have a family car, could learn about these cultures, and plan for a day when they could afford to visit. Furthermore, the slogan “See America” was patriotically blazoned across many guides whose covers were convincingly illustrated by the Graphics Division of the FAP. The covers and illustrations in the American Guide Series, along with other New Deal printed materials, exposed Americans to quality designs that were elevated to the status of consumable aesthetic goods.

Left: Poster promoting winter sports in New England, American Guide Series, WPA. Right: WPAPoster promoting the town of Sea Cliff to 1939 New York World’s Fair attendees

This development didn’t come out of thin air though, as the public had already been primed with an increasingly abundant commercial landscape. Since the full swing of American mass-industrialization in the 19th century, several generations of consumers had honed their taste for courtship from manufacturers and merchants. By the time the Great Depression hit, the public was used to being “sold to” through sophisticated visual adverting in journals, papers, billboards, and store signage. It is no wonder then that when so many saw their wallets shrink in the 30s, free cultural events at music halls, theaters, parks, museums, and art centers, became the newest goods of the day.

Reframing Diversity

The theme of diversity in the exhibition is reframed here through several critical lenses in order to consider the relationship between art and artifact and institutional roles in constructing historical and cultural value. For example, in the Journal of Art Education, author Sheng Kuan Chung illustrates how space and placement in the institution affect perceived value.

Cultural artifacts are automatically considered to be art if they are displayed in an authoritative institution such as an art museum permeated by the aura of art. Additionally, similar to those of art objects, stories of cultural artifacts are predominately constructed by museum authority through the curatorial process, including selection and presentation that “affects not just what the visitors see but how they are encouraged to construct meaning and understand their experiences. [19]

Indeed, Director Dana of the Newark Museum favored reproductions of artworks for their educational use, and he chose to elevate well-designed objects to the status of art as opposed to buying fine art.[20]

David Shirey, educator and art critic at the New York Times, once said in a review that “… an artifact is primarily the product of craftsmanship and skill, while a work of art is invested with an emotional, philosophical, spiritual or aesthetic quality that reaches beyond.”[21] However, Shirey went on to describe an exhibition of cultural artifacts comprised of rugs and tent furnishings as “artful” because of their aesthetic value. In this case, the objects he was discussing are normally classified as artifacts. However, they became art in the eyes of the viewer. Conversely, is it possible for artworks that are not aesthetically valued to be appreciated as artifacts instead? While this is possible, it is also likely that some of what humans make are both, as in the case of New Deal creative works, which often function as art and artifact of our histories. The architectural models exhibited are not only records of regional history and WPA history, but also creative works that reveal the hand of the artist. The diorama entitled Seal Hunting is an example of this. While created with funding from the Museum Extension Program as an educational display, close inspection reveals a freedom of technique not often found in works intended to be historically accurate. The delicate yet abstracted detail in the sculpture of the seal and the hunter evokes a rich imaginary scene without succumbing to literal exactness.The visual pleasure derived from peering into the glass and wood case, and momentarily becoming lost in the nuanced scene, Styrofoam snow and all, trumps the didactic component for which the model was made.Another example of this dual functioning is the contemporary arrangements of radios and audio speakers in the sound installations. They call attention to the constructed nature of sound and music in order to disrupt the more commonly assumed ephemeral nature of sound, especially when it is separate from image. Here, its physicality is revealed in the devices that project it. The adjacent radio is an index to access our understanding of the period, while the bare speakers that the sound comes out of mark our current place in time. The juxtaposition of these sound technologies highlights curatorial choice. At these stations, we can ask ourselves if the sounds in this exhibition are merely documents or new constructions. And while the labels provide answers, the momentary wondering opens up space to construct one’s own narrative.

Left: Mary Hoover, The Fairy Tale. ca 1930s. Right: Aaron Bohrod, Dreams, 1939

The majority of the works in the exhibition are juxtaposed against one another to challenge the designations that contemporary material culture traditionally assigns them. For example, comparisons of the subject matter in the painting Fairy Tale (Fig. 15) by Mary Hoover and that of Aaron Bohrod’s Dreams (Fig. 16) reveals an implied inequity between the subjects of the paintings. Bohrod’s work portrays an African American girl in wistful contemplation on a bare porch, while Hoover’s depicts a Caucasian girl reading a “fairy tale” in curtained space that is pointedly elegant and feminine. The representational intentions of Bohrod and Hoover are fairly apparent when viewed apart. However, when Fairy Tale is compared with Dreams, both become critiques of themselves for their class representation, and they call into question the position of the artist in relation to the people he or she portrays. The similarities and differences between the works create a space for the viewer to consider the artist as a constructor of narrative, and reflect on their motivations for that narrative. What is the artist’s relationship to the subject and how does this relationship effect their motivations? Perhaps the subject has no relationship to the artist other than the values they signify through their implied age, gender, and skin color. The subject can be an easy surface on which the artist imposes an imaginary and compelling identity for the benefit of the viewer. In the case of Dreams and Fairy Tale, they speak about themselves and the “other,” and they highlight the roles artists (and ultimately curators) play in constructing, dismantling, and reconstructing narratives on a work of art over the course of its life. For example, Hoover’s painting could easily be grouped with portraits and overlooked in other exhibitions or archives. Individually the works are benign, and are either entirely excluded from shows or displayed primarily because of their maker’s notoriety, as in the case of Dreams. While there is no way to always know the intentions of artists, or curators for that matter, the juxtaposition of artworks can create opportunities for additional considerations.

Photographs by the contemporary artist Mickey Everett further the critique of cultural valuing by unveiling the role that institutions play in assigning value and historical significance to the materials chosen for inclusion or exclusion from the archive. The juxtaposition of historic photographs to documents, sculptures, and paintings, reveals the impact of curatorship and institutional taste-making. For example, the image of WPA workers in Illinois salvaging archive materials from the Ohio Flood of 1937 literally and metaphorically illustrates the role government funding has played in historical preservation. Everett’s photograph of Gertrude Abercrombie’s Lonely House (Fig. 6), displayed in the exhibitionalongside the historical model of the Jackson County jail (Fig. 5), tells a story of unexpected similarities reaching across institutions. The choice to photograph the painting was the result of collaboration between Everett and me. I was interested in documentation of art and the archive, and he saw the potential in reaching out to the institution (specifically, the Birks Museum at Millikin University in Decatur, Illinois) where Lonely House resides. In this process, he saw an opportunity to capture an image of the painting, thereby indexing it for future reference, and bringing it into full color beyond the black and white image we had seen in a catalog. Everett revealed his role and the camera’s impact on the documentation by allowing the imperfections inherent in the camera lens to mark the final print with areas that range from sharp to soft focus. The image is reproduced at the exact scale of the original painting, calling attention to the camera’s indexical role as a documentary tool, and ultimately referencing the archive and the hand of the archivist. The dichotomy between the gesture of 1:1 representation and a seemingly imperfect capture create a space for the viewer to consider the many factors at work, such as technology, reproduction, and access, which transform historical knowledge over time.

Conclusion

This exhibition’s critique of the varied relationships between works, people, and institutions reframes the creative productions of the New Deal as significant works of cultural value for the present-day. The strong popularity of WPA/FAP posters and their reproduction as decorative memorabilia is proof of their enduring capacity for consumption. However, it is also important to look beyond the posters and even the frequently discussed murals, their bold graphics and vibrant messages, beyond the work that has reached so many people across so many classes, and to remember that there were thousands of diverse and talented individuals who are lesser known, but who produced equally significant art and culture.

These artists’ works are important for many reasons. First, they are original records of the period. As such, they function not only as aesthetic objects of varying quality, but also work together as artifacts to form a more complete picture of the New Deal period. What was once considered art may be less so today, but also what was once considered artifact may now be valued for its aesthetic characteristics, not only by scholars and institutions, but by everyday people wanting richer cultural experiences. It is also critical to develop an appreciation of a broader category of New Deal art now, in both global and local contemporary contexts, because it is tied directly to government funding of culture, something we are in short supply of these days. Lastly, the works and identities of the New Deal are considerably more varied than most people are aware of.It is the responsibility of people in many classes and disciplines who care about art, culture, and modern history to participate in a shift of perspective that includes a more nuanced history of the New Deal concerning its mediums, styles, and identities.

L: Dox Thrash, Defense Worker, c. 1941. Carborundum mezzotint. M: Unknown artist, Abstract Figure, c. 1935-1943. Plaster. Photograph by Gary Andrashko. R: Ida York Abelman, Machine and the Patterns, c. 1935. Lithograph. Photograph by Mickey Lee Everett

The New Deal was paid for by American citizens, and as such the federal government has a responsibility to make its history and legacy not only visible but also regularly accessible to the public. In fact, many scholars, artists, and curators today advocate for permanent government sponsorship of the arts. In the wake of the 2008 recession, Nancy E. Rose proposed in her book Put to Work: The WPA and Public Employment in the Great Depression that the American public would be well served by comparing the New Deal of the 30s and 40s to the considerably less ambitious National Recovery Act of the Obama Administration. While her research is not focused specifically on the arts, Rose emphasizes the importance of learning from past successes and failures of the programs, noting that some of the New Deal’s strengths were its scope and the related attempts to achieve a permanent work assurance program.[22] Beyond the success of the relief programs, the birth of Social Security, unionization, and labor laws (such as the establishment of minimum wage, maximum hours, and the illegalization of child labor) all owe their existence to the New Deal. Additionally, while the federal art programs ended on the eve of America’s engagement in World War II, the collective accomplishments of thousands of artists and administrators permanently changed the cultural landscape of the United States. The terrain between artist and public was transformed to increase access between the two. Citizens of all ages, genders, races, and social classes enjoyed the benefits of art centers, classes, exhibitions, and public artworks, giving them an opportunity to more closely engage with art. Through programmatic acknowledgement of their value, artists became everyday people and everyday people became beneficiaries of art in all its diverse forms.

In imagining the possibility of wide-scale federal support for the arts, advocates should take into account the past programs’ shortcomings. While Rose thoroughly points out the New Deal problems with “make work,” administrative inefficiencies, and discrimination, she doesn’t address the surprising destruction and neglect that New Deal artwork was subject to at the close of the programs. Today, the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) pursues the private possession of government–sponsored art in order to relocate these works in public institutions, in the hope of returning them to the citizens. Ironically, many individuals and private institutions cared for these works during a long period of government disinterest, and it has only been in the last two decades that the federal government has clarified who the true owners of the artworks are. This duplicitous history is a poignant reminder of the responsibility that all citizens, not only scholars, curators and institutions, have in ensuring our histories, and in constructing our present day culture through participation and advocacy. Americans urgently need the restoration of New Deal works, and deserve renewed broad support for the arts on a mass scale. Any detractors of government involvement in what is a seemingly subjective area like the arts should remember that it was impossible for something as massive and decentralized as the WPA (despite government ideology) to have produced any one effect or culture. Many voices, identities, and inventions formed a major historical moment that is by default diverse. That diversity is a cornerstone in our intertwined cultures.

Reassessing our past from fresh perspectives is urgently needed as well. Without this reframing of the artwork of the New Deal era, we perpetuate limited views about diversity in art in America that only serves to reinforce the hegemonic structures that are in place today. In our respective ways, we need to self-evaluate our continued indulgence of racism, patriarchy, and ideologies that homogenize our societal experiences, effectively distancing us from one another as human beings, and sheltering us from growth. As evidenced by the era between the wars, within the heart of the Great Depression, a program above all other programs lifted human dignity to heights that transformed us permanently.

Footnotes

- Gerald M. Monroe, “The Artists Union of New York.” Art Journal 32, no. 1 (October 1, 1972), 17. doi:10.2307/775601.

- U.S. Works Progress Administration, Report on the Progress of the WPA Program, June 30, 1938 (Washington, D.C: USGPO, 1938), 86. (as cited by James A. Finley in “The Works Progress Administration (WPA) and its Sub-Agency, the Museum Extension Project”)

- Belisario R. Contreras, Tradition and Innovation in New Deal Art (Lewisburg: Bucknell U.P., 1984), 161.

- Francis V. O’Connor, Federal Support for the Visual Arts: The New Deal and Now (Greenwich, Conn: New York Graphic Society, 1969), 28.

- Supervisors Association of the WPA Federal Art Project, Art as a Function of Government: A Survey(Washington, D.C: SA WPA/FAP, 1937), 20.

- Richard A Lawson and George J. Mavigliano, Fred E. Myers, Wood-Carver (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1980), 89.

- Susan Weininger, “Government-Supported Easel Painting in Illinois, 1933-43,” In Art for the People: The Rediscovery and Preservation of Progressive-and WPA-Era Murals in the Chicago Public Schools, 1904-1943 (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2002), 91.

- Francis V. O’Connor, Federal Support for the Visual Arts, 29.

- Donald S. Vogel correspondence with the authors George Mavigliano and Richard Lawson, December 12, 1983. Excerpted from quote in Mavigliano and Lawson, The Federal Art Project in Illinois, 25.

- Contreras, 169.

- For an example of compilations see The Guilds’ Committee for Federal Writers’ Publications, Inc. American Stuff: An Anthology of Prose & Verse by Members of the Federal Writers’ Project. (New York: The Viking press. 1937).

- For breakdown of FAP original artwork numbers by medium, not including prints, see O’Connor, ed. Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930’s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project (Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Society LTD, 1973), 305.

- Mavigliano and Lawson, 214.

- Mavigliano and Lawson cite the PWAP statistic of 15,663 from William McDonald, In Federal Relief Administration and the Arts: The Origins and Administrative History of the Arts Project of the WPA (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1969), 366. Section statistic of 1,600is from U.S. General Services Administration. “Federal Art Programs.” GSA (website). Accessed July 22, 2014. http//gsa.gov/portal/content/101818.

- O’Connor, Federal Support for the Visual Arts, 104. The figure for New York’s student attendance (only) of classes at 160 WPA-sponsored locations in the city was over 2,000,000.

- Victoria Grieve, The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 64-67.

- Ibid, 59.

- Contreras, Holger Cahill as quoted on 150.

- Sheng Kuan Chung, “Presenting Cultural Artifacts in the Art Museum: A University-Museum Collaboration,” Art Education 62, no. 3 (May 1, 2009): 34. Chung quotes Claire Robins, “Engaging with Curating,” International Journal of Art & Design Education 24, no. 2 (May 2005), 150.

- Grieve, 59.

- David L. Shirey, “Art vs. Artifacts in Montclair.” New York Times. February 15, 1981. Accessed July 23, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/1981/02/15/nyregion/art-vs-artifacts-in-montclair.html

- Rose, 89.

Jessica Allee holds a Masters in Art History and Visual Culture from Southern Illinois University Carbondale. She curated the exhibit New Deal Art Now: Reframing the Artifacts of Diversity, at the University Museum.