On September 1st the doors closed to the “Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany” exhibit at New York City’s Neue Galerie. It had been more than twenty years since the last major U.S. presentation on the infamous Nazi “Entartete Kunst” (“Degenerate Art”) show. Earlier this past summer I took a road trip with some friends to New York City — in large part as a pilgrimage to the Neue Galerie.

Along with Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, “Degenerate Art” was one of the most popular art events of the summer — a welcome counterpoint to the Whitney’s servile Jeff Koons retrospective. Both exhibits mark a revenge of history in the art world. Walker on the history of slavery in a deindustrialized Domino sugar factory. “Degenerate Art” on the incompatibility of modern art with fascist rule.

Michael Kimmelman, writing in the New York Review of Books, explains the draw of “Degenerate Art” largely in nostalgic terms, nostalgia for the lost past of a groundbreaking avant-garde:

A debased term, the avant-garde gets its jive back. Art matters again. The Nazis raised the stakes by stigmatizing modern art. As Genet once put it, fascism is theater. So modernism returns to its role as tragic hero in the show.

The record crowds that lined up on Fifth Avenue had more complex motivations. This exhibit was not merely about nostalgia for art’s edgier past. The history of modernist art is the origin story of contemporary visual culture and art. The Neue Galerie tells a key passage of this story; the battle between the best of what modernity could be against the worst of what modernity actually was.

Art is as much a spiritual process as something that can be explained scientifically or economically. The relics of the Neue Galerie exhibit are embedded with a magic quality. Here are the sacred artifacts of modernism: German expressionism in particular. Beside them are profane antagonists: the official, lukewarm and tepid art of Nazi Germany. When you are surrounded by these artifacts, including the related historical material, the weight of the exhibit is overwhelming.

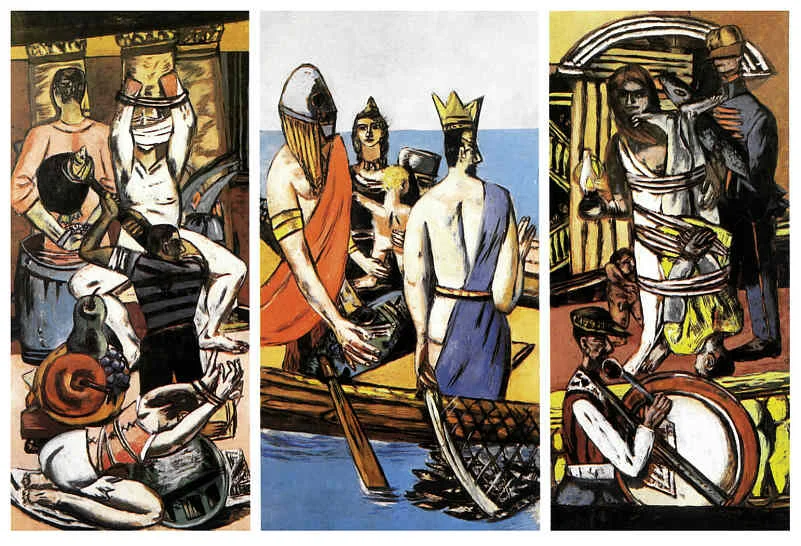

Separating the meaning of these artifacts from their history as degenerate art is not really possible. First of all, the artists themselves responded to their castigation in their work. The production of Max Beckmann’s masterpiece, The Departure, was entangled in Beckmann’s increasing harassment and repression. Secondly, the “presentist” knowledge we bring to the work — its status as a degenerate — has been fused with its “original” meaning.

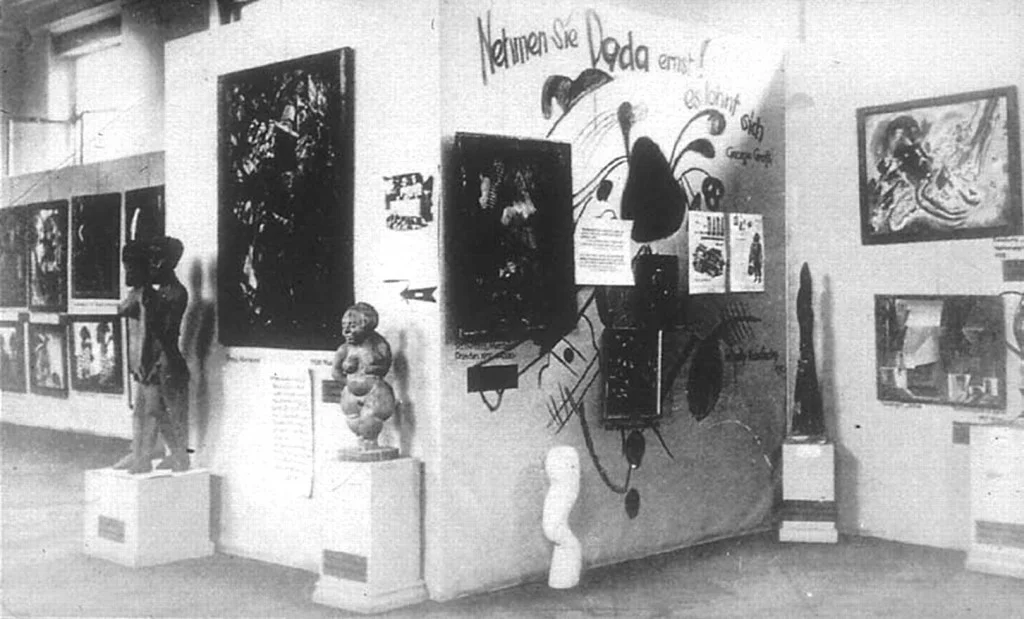

Installation view of the Degenerate Art exhibition at the Neue Galerie in New York — with official Nazi art seen on the left and modern art on the right

American academics have long been plagued by overly analytical thinking—and with that a marked lack of imagination. Two seemingly opposed realities can be true at the same time. It is possible to see these works as inseparable from the mojo imbued in them (good and bad) as “degenerate,” and at the same time approach them in a serious, scientific and historical manner. This is what the Neue Galerie has done, retelling a nuanced story (both in the gallery spaces and the exhibition catalog) of the battle between Nazi and “degenerate” art, the contradictions within each, and the histories of both.

As Michael Blum argued on Hyperallergic, the strength of this exhibit is in its “deliberate… historicizing.” The Neue Galerie has “suspended the use of ‘degenerate art’ as a designation for all modernist art, instead coolly poking around the interior of tis expanded meaning” by focusing on the actual work included in the infamous 1937 exhibition.

Degenerate Origins

The origins of the idea that art could be degenerate were bound up in the social and economic transitions of the nineteenth century. In Germany this related directly to the urbanization and industrialization of the country, national unification under conservative rule, an increasingly cosmopolitan urban life and a growing socialist movement. This produced reactions against modernity at various levels of German society, on the left and the right.

“Over the course of the nineteenth century,” Olaf Peters writes, “concepts such as decadence and degeneration increasingly found their way into both cultural criticism and scientific discourse” (Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937, edited by Olaf Peters, 16).

The first major theorist of these concepts, writing in German, was Max Nordau (1849-1923), the son of a Budapest rabbi and later a co-founder, with Theodor Herzl, of the World Zionist Organization. Nordau argued that the degeneration of society was not unlike a mental illness “caused by rapid changes to modern civilization” (17). City dwellers were a flawed “human type… fated to perish” (17). Likewise, modern art and literature were “sick” and “degenerate” (17). The modernist idea of artistic genius was the praise of “highly-gifted degenerates” and modern art and culture were infected, as if by a disease: “We stand now in the midst of a severe mental epidemic; a sort of black death of degeneration and hysteria…” (18).

Krupp works, Essen (1890); Alexanderplatz, Berlin (1903); Max Nordau

The modern idea of genius was a bourgeois adaptation of medieval and classical notions of spiritual inspiration redirected toward the celebration of the individual. In Germany, however, with national unification and industrialization pursued by conservative forces after the defeat of the 1848 revolutions, certain bourgeois cultural notions rose to prominence as dissident ideas. A similar pattern occurred in most European nations, to various degrees. In all cases a minority of the ruling-classes patronized the avant gardes. Frequently, it was radical artists, sometimes tied to oppositional politics, who carried the torch of what bourgeois culture would become.

At this time it was not unusual to hear reactionary lamentation. Conservatives frequently protested that poetry that deviated from classical rules was “decadent” (40). Nordau, however, went beyond this, placing the degeneration of art and culture in medical, mental, criminal and Darwinist terms. For example, Nordau argued that impressionist paintings were produced by a diseased visual cortex.

Degenerates are not always criminals, prostitutes, anarchists and pronounced lunatics; they are often the authors and artists. These, however, manifest the same mental characteristics, and for the most part the same somatic features as members of the above mentioned anthropological family, who satisfy their unhealthy impulses with the knife of assassination or the bomb of the dynamiter, instead of with the pen and the pencil… Some among these degenerates in literature, music and painting have in recent years come into extraordinary prominence, and are revered by numerous admirers as creators of a new art, and heralds of the coming centuries (41).

While the Nazis would (quietly) borrow much of Nordau’s analysis, Nordau himself believed that natural selection would, on its own, weed out the “degenerates” within a few generations. Nordau, seeing himself as a standard-bearer of Enlightenment ideals, believed, not entirely without reason, the rise in continental anti-Semitism was a product of the new modern world; a part of the degeneration he decried. Nevertheless, as Mario-Andreas Von Luttichau argues in the exhibition catalog, Adolf Hitler was aware of Nordau’s contribution to the concept of a degenerate art: “Many of Nordau’s theories on degeneration can be found in Hitler’s Mein Kampf, although he avoids at all costs citing his source” (42).

The Nazi program for art was, at first, confused, and represented rival factions within “National Socialism.” Hitler was an infamously failed artist, twice denied entry to Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts. Fascism, however, is best understood as a middle-class social movement. Nazism, before rising to power, was racist, anti-working-class and reactionary, but it was not completely homogenous in its approach to modern art. The reactionary forces it awoke, however, tended to be in agreement that modern art, an art that it could not understand, was a scam, a scam perpetrated by a global bourgeoisie, Jews and the international socialist movement.

Emile Nolde’s “Prophet.” Nolde, despite his membership in the Nazi party and active support for the regime, was banned from making artwork and had more than 1,000 works seized from German museums.

Before 1933, and the Nazi consolidation of power, there were efforts to win over “intellectual creators” to the movement (22). This trend was most associated with party “intellectual” Alfred Rosenberg. The National Socialist Scholarly Society was formed in 1928 and later renamed the Militant League for German Culture, or Kampfbund (22). The Kampfbund’s ties to the Nazis were (partially) concealed. According to Peters, by 1930, Rosenberg began to show some progress in building ties with conservative academics and showing an “appearance of intellectualism” (23).

At the same time the impulse in the regional and rank-and-file sections of the party tended toward “spontaneous” anti-modern art actions. In 1930 the Nazis joined the local government in Thuringia and Dr. Wilhelm Frick became the Minister of the Interior and Education. He made the attack on “Marxist [cultural] impoverishment” a focus: “Organized subhumanity has reigned in Germany for twelve years now. The rule of the inferior is the necessary consequence of the corrupt parliamentary system” (24). Art and jazz music were censored in Thuringia (26). Modern art was confiscated from museums.

In the summer of 1930 Oskar Schlemmer’s frescoes in the stairwell of a Bauhaus building in Weimer were destroyed. Local Kampfbund members organized semi-spontaneous “exhibitions of shame” (schandausstellungen) in Dresden, Karlsruhe and Mannheim (27). Such exhibits went hand in hand with the street repression that followed the Nazi rise to power in 1933: “[O]n April 4, 1933, just a little more than two months after the Nazis took power, the exhibition “Kulturbolshewistiche Bilder” (Cultural Bolshevist Images), a harbinger of the exhibition ‘Entartete Kunst’ opened in Mannheim” (28). In tandem with this shaming exhibit a show of “exemplary” German art was organized.

“Cultural Bolshevist Images” included artwork by Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, James Ensor, Paul Klee, Emil Nolde and Oskar Schlemmer. The works were labeled with the name of the artist, title, year of museum acquisition, purchase price (not adjusted for inflation, in order to make the purchase of the works seem like a waste of taxpayer money), and sometimes the race of the artist. Jewish art dealers, depicted much like snake oil salesmen, were considered key to modern art’s success (29).

In 1933, the Kampfbund published an article by a right-wing painter, Bettina Feistel-Rohmeder, titled “What German artists expect from the government”: “materialism, Marxism and communism [should] not only be politically persecuted, prohibited and exterminated but also the spiritual struggle… now be taken up by the whole of the people and the destruction of bolshevist nonart and nonculture be vowed” (44).

The enemy was vilified in populist (anti-bourgeois), political (anti-Marxist) and racial (anti-Semitic) terms. These in turn were related to the ideas of mental and racial hygiene articulated in the 19th century, including many of the ideas formulated by Max Nordau. Images of modern art were coupled with images of the psychologically and physically ill.

These initial steps of the Nazis were not centrally coordinated. The Nazi impulses against cosmopolitan society, toward anti-Bolshevism and anti-Semitism, pushed their cultural policies in a particular direction, but there was not a consensus on modern art itself, particularly when it came to German expressionism. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, was skeptical of local attacks on modern art:

We National Socialists are not unmodern; we are the carrier of a new modernity, not only in politics and in social matters, but also in art and intellectual matters.

As Neil Levi argues in October, “[p]rior to 1937, the position of German Expressionism [the main domestic art target of the Nazis] within Nazi cultural politics was hotly contested, part of a struggle between Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels for control of Nazi cultural policy.”

Within a few years, however, Goebbels would personally lead the charge against modern art, using the Reichskulturkrammer (Reich Chamber of Culture) to assert his dominance over Rosenberg and solidify his standing with Adolf Hitler (31).

“The Great German Art Exhibition”

On Sunday, July 18, 1937 the “Great German Art Exhibition” opened in Munich. As Ines Schlenker writes, “the city had been gearing up for this event for days with public fairs, concerts, opera, and theater performances. On the day of the opening, an elaborate historical pageant wound its way through the expansively decked out streets to commemorate… ‘two thousand years of German culture’” (91). “A few hours earlier,” she continues, “in the Hall of Honor of the newly erected… House of German Art, Adolf Hitler himself held the inaugural speech, boasting about the trend setting quality of the exhibition” (91). Behind the scenes, however, Hitler was sorely disappointed at the exhibition in the “Temple of German Art” (91)

Hermann Otto Hoyer’s In the Beginning Was the Word; The House of German Art

In the most vulgar terms the “Great German Art Exhibition” was a success. Held annually after 1937 until the end of World War Two, it drew growing audiences each year. Propaganda and racism conspired to conceal its crass commercialism. “In Munich, pictures for 250,000 Mk sold already,” Goebbels noted in his diary, “This is a great success” (92). Altogether in 1937 more than 500 works were sold for three-quarters of a million RM. By 1943 that number grew to four million (92). Conceptually, however, the exhibitions were largely incoherent—formed most of all by Hitler’s personal tastes. Even right-wing artists and curators often proved useless in the plans for a new German race art (93).

When the idea of a Nazi organized “grand survey of contemporary art” was floated in 1936, there was an effort to reach out to expressionist artists like Emil Nolde, Ernst Barlach and Rudolf Belling. Their work, in 1937, would be labeled as degenerate (93). A nine-person jury of artists was selected (as per Munich tradition) to curate the exhibit. They too failed the Reich.

Accompanied by Goebbels, Hitler came to inspect the proposed choices on 6 June 1937, only weeks before the scheduled opening. Fuming with rage, he decided to take matters into his own hands. He ordered works to be taken down and replaced the jury with Heinrich Hoffman, his close friend and personal photographer (93).

The first room of the re-organized “Great German Art Exhibition” featured a portrait of Hitler flanked by paintings of a German soldier in WW1 and Nazis preparing for street battles in 1933 (93). In another hall Hermann Otto Hoyer’s In the Beginning Was the Word featured Hitler speaking to an early gathering of Nazis. Aside from these paintings, and busts of Mussolini, Ataturk and a few others, most of the artwork selected was not overtly propagandistic. Much of it consisted of idealized visions of peasant life, landscapes and classical (and disturbingly Teutonic) nudes. The inchoateness of the exhibition meant some artists, Rudolf Belling for example, were included in both the “Great German” exhibit and the “Degenerate “exhibit at the same time (100).

Heinrich Hoffman lamented that “no genius like Manzel, Kaulbach, Schwind and so on emerges from the contemporary painters in spite of all the sponsorship” (104). The first “Great German Art Exhibit” drew 500,000-odd visitors. Across the street, however, the “Degenerate Art” exhibit drew some two million (49) – four times the audience.

“Degenerate Art” (1937)

The “Dadaist” section of “Degenerate Art”

“The Negro becomes the racial ideal of degenerate art in Germany” – a slogan commenting on the art of Paul Klee, Vasily Kandinsky, and others, on the walls of the “Degenerate Art” exhibit in Munich, 1937 (36).

“Degenerate Art” was most of all the product of the failure of the “Great German Art Exhibition.” Goebbels hastily organized the event to outmaneuver his rivals after Hitler’s considerable disappointment in the latter. Unable to define Nazi art in positive terms, negative terms were employed: this is what new German racial art was not.

In the general climate of disappointment with its own official production of art, faced with the continuing campaigns of Rosenberg and his types, and after the dramatic loss of prestige suffered by members of the Reichskulturkammer, and hence of Goebbels himself, with regard to the jury for the ‘GDK,’ the minister of propaganda cleverly seized the initiative… in order to make an impression on Hitler with his especially radical approach. (111)

The Neue Galerie counters the emptiness of the official art to the complexity of the degenerate—although curator Olaf Peters presents both in a detached modernist idiom. The results are striking. Adolf Ziegler’s Four Elements—depicting four academically constructed blonde female nudes—is displayed opposite Max Beckmann’s expressionist Departure.

On July 19, 1937, one day after the launch of the “Great German Art Exhibit,” Adolf Ziegler, a Nazi painter and president of the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts, opened the “Degenerate Art” exhibition in the plaster cast galleries of Munich’s Archeological Institute, saying: “You see around us monstrosities of madness, of impudence, of inability, and degeneration. What this show has to offer causes shock and disgust in all of us” (36).

As in the earlier shame exhibitions the names of artists were listed, along with the price paid for work, and the statement “purchased with the taxes of the working German people.” Comments on printed material and on the walls chastised and derided the artwork:

Mockery of the German woman-ideal: cretin and whore…

Conscious sabotage of the military…

German farmers seen from a Yiddish perspective…

Jewish yearning for the desert is vented…

This is how sick minds viewed nature…

Revelation of the Jewish racial soul… (38)

Texts mocked the ballistic scrawl of the Berlin Dadaists, ironically miming Dada’s call for an anti-art (49).

The work in “Degenerate Art” was almost entirely that of German artists. The Nazis had already seized thousands of modern artworks (usually those made after the arbitrary date of 1910) by artists of various national backgrounds. But “Degenerate Art” aimed to shame German artists—Jewish and otherwise (although most artists included were not Jewish). Almost all works were condemned for being un-German, Jewish and Bolshevist — opposed to the “blood and soil” values of “true” German art.

Felix Nussbaum’s “The Damned” – painted while he was hiding from the Nazis

Following the German Revolution (1918-1923), the Weimer Republic had become a hotbed of avant-garde artistic activity, building on (and sometimes rejecting) the pre-war contributions of German expressionism in the Blue Rider and Bridge groups. Post-war expressionists, Dadaists and surrealists rounded out the bogeymen of modernist art. Some rooms were separated by theme. One room was comprised of works considered anti-religious, another of works by Jewish artists, yet another of works deemed insulting to German womanhood. Other rooms in the hastily constructed exhibit lacked any theme at all.

Artists included in the Degenerate Art show included: The expressionist Max Beckmann, who fled Germany on the opening day of the exhibit; Max Ernst, the surrealist painter, who also fled Germany; Paul Klee, painter and friend of Walter Benjamin, who was exiled in Switzerland; Otto Dix, famous for his antiwar paintings of World War I veterans, who fled to the countryside; Emil Nolde, expressionist and Nazi party member, who was forbidden to make artwork or purchase art-making materials; George Grosz, former Berlin Dadaist, communist and painter, fled to New York; Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, expressionist painter, driven to suicide; Felix Nussbaum, killed in Auschwitz in 1944 at the age of 39.

Following the first “Degenerate Art” exhibition, Adolf Ziegler was charged with a second culling of modern art, confiscating 17,500 more works from German museums. “Degenerate Art” exhibitions became seasonal events over the following years (47) and a catalog was written, The Degenerate Art Exhibition Guide, divided into thematic groupings:

- “Formal deformation”

- “Insult to religious feeling”

- “Call to class war”

- “Depiction of moral decay”

- “Portraits of people without the Aryan ideal of race”

- “Relationship of art to the mentally ill”

- “Works by Jewish artists”

- “Complete insanity” (48)

“[O]n nearly every page,” von Luttichau writes, “the exhibition guide mentioned the purification of the body of the people from communists, Jews, the ill, bolshevists, prostitutes, cretins — a reaction fueled only by blind fanaticism and Nazi racial ideology.” (48)

Modernism and fascism

The horrendous truth of the Nazis — and fascism more generally — is that they were a product of the very modernity they posed against.

Neue Galerie

It is important to admit that modernity did fail in the early-middle 20th century, producing Stalinism, fascism and Nazism — and the social and economic conditions that allowed these things to come to power. But modernity was not a monolith. Modern societies were not based solely on ideas, Enlightenment or otherwise. They were based on their political economies. The particularities of Nazism rose from the contradictions of a strong but politically paralyzed German working-class during the crises of the inter-war period.

“Cultured” liberals might console themselves that modernity triumphed over crude fascism. But it was largely the failure of liberal and social democratic politics that produced fascism in the first place — to horrific results both on human and cultural terms.

As Holland Cotter notes in the New York Times, when walking into the first hallway of the Neue Galerie one is surrounded by two photographic murals: on one side visitors waiting to enter the “Degenerate Art” exhibit in Hamburg in 1938. On the other it shows Jews arriving at the railroad station in Auschwitz. These were not independent phenomena, but part of the same process.

Olaf Peters does not aim to reconstruct the entirety of the historic exhibitions—or a survey of important artists involved. What matters here is the history itself, represented in the selected artwork, photographs and other artifacts, including ledgers of seized works and empty frames of lost and destroyed works on the wall.

“National Socialism,” as Walter Grasskamp writes in his essay, “Entartete Kunst und documenta I” “represented an attempt to obscure a modern world with an anti-modern ideology [that] gratefully took up the self-proclaimed closeness of artists to the mentally ill as an indication that every other attempt to come to terms with modernism was condemned to fail.” (49)

This concealment was a direct byproduct of the failure to resolve the great contradiction of modern society: the conflict between labor and capital.

The Nazis used, at times, language inherited from the Romantics, just as they posed as “socialist” and anti-bourgeois. Unlike traditional Romantics, even conservatives like Edmund Burke, they did not really seek a return to pre-modern times or a rapprochement between modern and aristocratic society. The Nazis did invoke a pre-capitalist past, but this concealed their role as capital’s battering ram against labor. It concealed their role as the economic, cultural and political goons of capitalism in crisis. The Nazi obsession with technology and bureaucracy was alien to the Romantic worldview.

Even the third rate painters and sculptors of official Nazi art were somewhat alien from the true reality of Nazi ideologies and life. Their idyllic landscapes and peasants mimed a past that bore little genuine relationship to the industrial war machine reigning in Germany. This tremendous gap was part and parcel of the Nazi cultural regime. There was, of course, no Nazi “soul”—no identity beyond its murderous function.

As Olaf Peters argues:

It was always one of the National Socialists’ techniques for power — not least because the balance sheets of their own achievements was often rather modest–to disparage their opponents, to produce a propagandistic image of the enemy in order to mobilize energy and to proclaim an apparent state of emergency (114).

Following the 1937 Munich exhibition the Nazi propaganda machine would turn this method increasingly toward its ideals of racial hygiene and purity, culminating in the Holocaust. In the film, The Eternal Jew, modern art represented the assault of non-German “Jewish-Bolshevist” ideas on “old German, Western art” (120). This was put in increasingly more existential racial terms. Writing about the publication of the 1942 SS brochure, Der Untermensch(The Sub-human), Olaf Peters observes:

Confronted with the situation of the war in the east, which was turning against the Germans, Heinrich Himmler’s SS evoked the terrible image of bolshevist subhumans destroying the art and culture of the West, leaving it in rubble and ashes, and slaughtering masses of innocent people (120-121).

Post-Script: Departure and Revenge

Max Beckmann is one of my most favorite artists; he is up there with Goya, Beuys, Brecht and Shakespeare. There is an excellent collection of his pieces at the St. Louis Museum of Art, not far from my hometown, and I would visit them regularly in my youth.

Max Beckmann, “The Departure”

Beckmann was no socialist. He was even willing, after 1933, to try to work under the new Nazi regime. It proved impossible. He fled, eventually to the United States, and for a time taught at Washington University in St. Louis. But Beckmann’s art did something more profound than even the most cutting photomontages of John Heartfield. Arthur Danto described Beckmann’s art, and Departure in particular, as “the mythography of wounds.”

This is (part of) what is needed on an artistic and cultural scale – a mythography of wounds. We are wounded by the failure of the great revolutions of the 20th century. We are wounded by the reactions that followed those failures – in Russia, Italy, Spain and Germany. We are wounded by a thousand cuts everyday, in Ferguson, Missouri and beyond, going back centuries and millennia. If history is to have its revenge in art and culture, we cannot aim to represent a future utopia in our work or merely the latest mobilization; we must raise to the level of myth ten thousand years of injury, pain and injustice. As Walter Benjamin wrote, in 1940, in “On the Concept of History”:

This consciousness, which for a short time made itself felt in the “Spartacus” [forerunner to the German Communist Party], was objectionable to social democracy from the very beginning. In the course of three decades it succeeded in almost completely erasing the name of Blanqui, whose distant thunder [Erzklang] had made the preceding century tremble. It contented itself with assigning the working-class the role of the savior of future generations. It thereby severed the sinews of its greatest power. Through this schooling the class forgot its hate as much as its spirit of sacrifice. For both nourish themselves on the picture of enslaved forebears, not on the ideal of the emancipated heirs.

That is why I went to see the exhibit at the Neue Galerie — to nourish myself on such pictures; to say a silent oath for revenge.

*All parenthetical page references are to the show catalog.

Adam Turl is an artist and writer in St. Louis. He is on the editorial board of Red Wedge and writes the "Evicted Art Blog."