I: (Re) Introducing a Misunderstood Musical

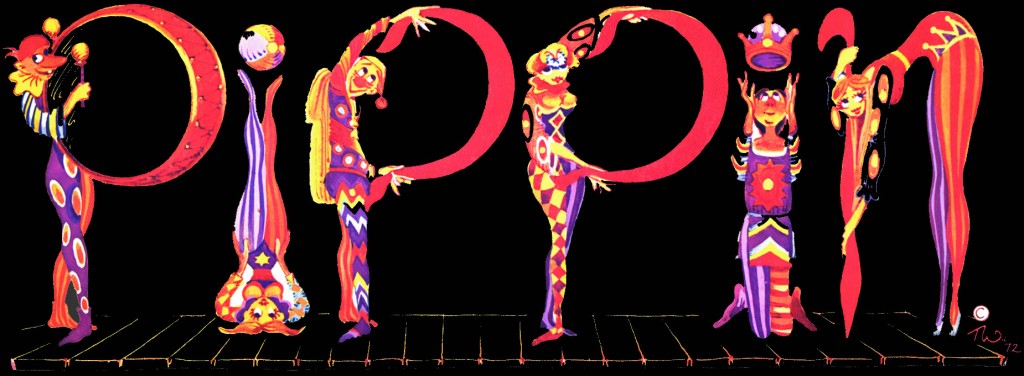

It might seem silly, peculiar, or just plain naive to make of the revived musical Pippin! an occasion for serious social, political, philosophical reflection, (even if one accepts the premise that Broadway musicals can produce meaningful social commentary in the first place). Despite being nominated for ten Tony Awards in 2013, and winning four of them, including Best Musical Revival, Best Director, and Best Lead Actress, Pippin! still can’t seem to get much respect as far as its substance is concerned, even from those who appreciate its style. Pippin! gives us plenty of “magic,” the critics contend, but little in the way of meaning.

A New York Times review by Ben Brantley, tellingly entitled, “The Old Razzle Dazzle, Fit for a Prince,” describes the revived Pippin! as a “99-pound musical…a work in need of camouflage, a skeleton that requires savvy stagecraft to give it flesh.” Lauding the talent of the amazing acrobats that have been incorporated into this new production [1], and recognizing the entertainment value of what amounts to a “sensory assault,” Brantley argues that “Ms. Paulus’s “Pippin!” is often fun (with an exclamation point), but it’s almost never stirring.” He adds that “in [so aggressively] courting its audience, this “Pippin” is ultimately more cynical than Fosse’s” softer and more sensual 1972 original. [2] Closing his review, he likens this “21st century” Pippin! rather provocatively to the “bread and circuses of the Roman Coliseum, crowd-pleasing show business as usual.” [3]

Such back-handed praise fits the mold set by Clive Barnes original NY Times’ review of Pippin! upon its Broadways debut in 1972. Barnes heaped praise on the Imperial Theater production for its performance values and directorial pizzazz (singling out the performance of rising star Ben Vereen as Leading Player), but he derided the substance ofPippin!’s score and book alike. Though “launched into space” by Bob Fosse’s “fantastic” staging, Pippin! is deemed a “painfully ordinary show,” built around a “trite and uninteresting story with aspirations to a seriousness that it never for one moment fulfills.” Of Pippin!’s plot, which follows the earnest son of Charlemagne on a quest for meaning that takes him from the university, to war, to sexual frolic in the countryside, to revolutionary aspirations that culminate in patricide and a short stab at political leadership, to a final but ambivalent embrace of “ordinary” domestic life, Barnes wrote, “It is a commonplace set to rock music. ” The “Finale,” which brings a desperate Pippin to the brink of self-immolation for the sake of achieving at least one perfect, spectacular moment of glory, Barnes deems a “lame duck ending” — one that not even the great stage-skill of Fosse can redeem. (Spoiler: Pippin refuses to burn himself up for the pleasure of the Players and the audience, returning to Catherine and Theo, the widow and child from which he has bolted just the scene before. This closing act of rebellion outrages the Leading Player, who then orders Pippin and his newfound family stripped of all stage magic: costumes, make-up, lights, and even orchestral music.) For Barnes, “The book is feeble and the music bland,” though the staging, the dancing and costumes, and the performances, make the show well worth seeing.

For both Barnes and Brantley, Pippin, as musical and as character, function(s) mainly as a dummy skeleton upon which to heap the magical robes of showmanship and spectacle. This is “sensory assault,” “fun” entertainment, not “stirring” art, let alone meaningful social reflection. Pippin’s quest for Meaning is merely the excuse to show off the Magic; the Players, ostensibly the mere presenters of the plot, the background against which “The Life and Times of Pippin” emerges, are themselves truly the stars. The nominal hero is the sideshow, a mere excuse for players to play (and for audiences to enjoy — after all, without the structure of “meaningful” plot development they might feel guilty for taking so much masturbatory pleasure in “mere frills”).

What doesn’t come through such reviews, however, is the way in which Pippin! does not simply offer up “Bread and Circus” spectacle [4], but rather, through its Brechtian show-within-a-show structure, offers us critical commentaryon such spectacle — at least when staged properly— calling attention to deadly dangers of “mere” diversion, even as,yes, yes, it keeps on diverting us. The commentary is often playful — at least until the bitter end — but is not without seriousness, insight, or contemporary resonance. (It’s not without its limitations and contradictions either, but even these, I will argue, are significant, perhaps even socially symptomatic, opening entryways for critical reflection.) To the point: The seductive but deadly spectacular magic of modern stagecraft is not only the star of the show, but one of its main targets. Indeed, I want to argue that Pippin!’s spectacular reflections may be more acute today, in the age of cynical and sadistic mass culture and ubiquitous “Reality TV,” than they were when the show was first produced in 1972. Waist deep in the swirling corporate mass cult slop of 2014 — as the culture industry’s profit anxiety leads them to cut costs, writers, and standards alike, sucking at dry eyeballs with spectacular storms, capitalizing on ubiquitous image technology and a precarious “real economy” that leaves millions desperate for a shot — or a whiff — of “success,” Pippin! takes on new relevance and resonance. In an age that has given us The Jersey Shore, Real Housewives, Octomom and Big Brother, where the elbow-and-skull-porn of Ultimate Fighting has gone mainstream and the televised killing fields of The Hunger Games no longer sound so far fetched, Perhaps Pippin!’s time has finally come?

Director and choreographer Bob Fosse

As sketched above, Pippin! relates the story of Pippin, first-born son of Charlemagne, as he searches for “something completely fulfilling.” We first meet him at his graduation (with high honors) from the University of Padua, where he explains to his former teachers that what he is looking for “can’t be found in books.” In “Corner of the Sky” he explains his aspirations to find his proper place in the world and to achieve greatness with his life. From here, Pippin returns to court, eventually convincing his tyrannical and stubborn father to allow him to join in the upcoming military campaign against the “infidel” Visigoths. Excited to be a part of “Something Big,” Pippin is horrified by the actual violence of the battle, as well as the prospect of “raping and sacking” that is to follow the “glorious” victory, particularly so after having a sympathetic conversation with a slain (and decapitated) Visigoth warrior. After Academe, War becomes the second realm that fails to fulfill. Fleeing the battlefield, Pippin retreats to the countryside to visit his grandmother, Berthe, who advises him to enjoy himself, to not “think too much,” and to seize the day (in the sing-a-long, show-stopper “Just No Time At All”). Pippin takes Berthe’s advice to the extreme, stumbling from summer romance into an extended orgy of Sex and Drugs, all of which ultimately leaves him feeling “empty and vacant.” Finding Pippin depleted and despondent, the Leading Player prompts him to take up Politics, relaying to him the news of his father’s tyranny, including the recent slaying of thousands of peasants who have risen in revolt. Pippin’s longstanding resentment of King Charles quickly merges with an urge for justice, as he morphs into a rousing mix of politician and revolutionary headed towards the end of the first act.

After assassinating Charlemagne at prayer at Y’Arles, Pippin assumes the crown with radical, populist ambitions, but quickly finds administering the realm to be difficult, nay, impossible. His agenda of liberating the peasantry (“the land shall belong to those who work it”), falls by the wayside when a barbarian invasion threatens; Pippin quickly cancels land reform in order to keep taxes flowing from the nobles; the lucre is necessary for paying the army, we are told. Within a matter of stage seconds Pippin finds himself acting just as tyrannically towards his subjects as his father had — even ordering the hanging of a peasant man who denounces him for his betrayal.

It’s worth noting that taking the radical road to justice is shown to be “impossible” by false logic, through a rather blatant blind-spot—namely by neglecting the possibility of cutting out the nobility entirely and having the newly liberated peasants either pay taxes directly or raise the requisite army themselves (sans tax) to meet the invading “barbarians.” [5] What the “Politics” section of the musical actually “proves” is not the inadequacy of radical idealism to rule, but rather the inadequacy of such idealism to rule if it is not willing to go all the way to fulfill its egalitarian promise, revolutionizing even its own inherited structures of class and governance. That said, the staging of the moment seems designed to lead audiences to (mis) interpret this rebel-to-tyrant turnabout as representing some greater irony about would-be revolutionary regimes, and how in practice they “inevitably” end in tyranny and hypocrisy. (Lenin must turn Stalin etc etc.)

Into Pippin’s desperation and newfound panic returns the Leading Player, who, like a genie sprung from a bottle, seizes on the wayward son’s wish, to grant him the ultimate mulligan. Promptly producing the corpse of Charlemagne, the LP offers Pippin the chance to resurrect the slain king; Pippin pulls the dagger from the chest, instantly restoring the tyrant to power, and freeing Pippin of his newly assumed responsibilities. Looking as vigorous as ever, King Charles accepts Pippin’s bowing apology without missing a beat. “That’s alright, son,” he exclaims, wagging a parental finger before exiting the stage to resume running the world, “Just don’t let it happenagain!”

It is a line that always gets a big laugh. A laugh, I want to suggest, that expresses more than surprise, but also relief, not only relief that Pippin won’t have to deal himself with the mess he’s just made (and that we won’t have to sit through that process: no fending off the barbarian invasion, no putting down the peasant uprising), but relief that the show, in summoning dear Dad the Despot back to life, washes its hands of politics and serious passion altogether, retreating to (or perhaps reassuring the audience that it had never truly left) the realm of comedy, where — where “as we all know” — the hijinks of wayward youth never amount to much.

John Rubinstein as Pippin and Jill Clayburgh as Catherine in the original production, 1972

The funniness of the line stems from the sudden shift of registers; we move from the realm of public, historic matters, matters of truth, justice, and revolution, to the realm of private family misdeeds, of forgivable teenaged trespasses without consequence — from the tragic realm of Hamlet…to the sitcom farce of Father Knows Best. [6] The assassination of the King having been enacted as a Political — and implicitly transformative, quasi-collective, revolutionary — act (see the song “Morning Glow”), is undone, and, in the process of the undoing, rewritten as (having always been) a naïve, merely Oedipal act. Political “Revolution” is retroactively recast as the mode of appearance for what is fundamentally a matter of “growing up,” a generational conflict, a pseudo-existential, teenaged “rebellion” where identifiably, ostensibly leftist sentiments — opposition to military aggression abroad, class oppression, social inequality, and state repression at home — are cast as excesses of “youthful idealism.” [7] Reading this crucial comic turn (and Pippin’s own fleeting radicalization) allegorically against the backdrop of its historical moment, the youth rebellion of the Sixties appears here to be not so much about overthrowing the war machine, imperialism, racial apartheid, and patriarchal tyranny, as rebelling against one’s parents, a developmental phase, to be tolerated, but not taken too seriously. (“Just don’t let it happen again!”)

It’s by now a familiar way of recasting and depoliticizing the Sixties, not to mention a convenient way for those who revolted against the establishment (as well as those who didn’t, who defended it or accepted it) to justify and in fact retrospectively naturalize their abandonment of the Cause, their acceptance (eager, begrudging, or cynical) of the inequities of capitalism and the barbarities of empire as inevitable if perhaps regrettable facets of the “Real World” in which we live. That this deflating comic trope was present already in Pippin! in 1972 — when the tear gas from the state murders at Jackson State and Kent State had barely cleared, when American bombs still rained down across Southeast Asia — is remarkable. Developing the original version of Pippin! in the halls of Carnegie Mellon University prior to his graduation there in 1968, Stephen Schwartz appears to have guessed the way the wind wouldeventually blow back. [8]

Quickly retired from politics, Pippin goes on to try “Art” and “Religion,” (for ten to twenty stage seconds a piece) only to find each realm lacking (for reasons more institutional than inherent, it’s worth noting) [9]; he still feels “empty and vacant,” unable to discover “something completely fulfilling,” or to find “his corner of the sky.” Following an exciting but unsuccessful attempt by the Leading Player to rally his spirits (in “The Right Track”), Pippin collapses in despair at the side of the road. Here he is found by Catherine. (We will pick up the plot and her crucial role in it, below, in Part 3.)

* * *

Pippin! is framed as a show within a show, facilitated by a troupe of Players, headed by the Leading Player who serves as emcee for “The Life and Times of Pippin” (frequently addressing the audience directly) as well as boss-manager of the player troupe (at times chastising or covering for those Players who lapse in their proscribed duties). Indeed, the interplay between these frames — each character, except for Pippin, simultaneously representing a character and a (self-conscious) player — creates much of the comic and potentially critical charge.

Much of the real zap comes at the end (to which we will return), but static builds and sparks fly throughout. For instance, consider one of the show’s iconic moments: Fosse’s famous soft shoe trio, which appears at center stage in the middle of the number “Glory,” while Charlemagne’s soldiers tear “infidel” Visigoths limbs from limb in silent slow motion in the background — much to Pippin’s horror. It’s an entertaining, impressively synchronized dance number to be sure, (often eliciting a show-stopping ovation) but it’s simultaneously a haunting commentary on how “entertainment” can cover up murder, how style and stage-location mask butchery and madness. While the dancers hold our attention, nameless “enemies” are murdered brutally in the background. In the original version, the Leading Player rallies us to pray to God for the glory of Charlemagne and courts our applause for his fancy footwork, stepping and high kicking his way through decapitated heads and severed limbs. We are to laugh and clap along as the infidels are slaughtered. Ha ha ha. Huh.

In an early world tour recording of the production (available via Youtube [10]) the critical edge of this scene is sharpened by the interjection of a radio “countdown” of the “all-time greatest” wars in terms of numbers killed and wounded, presented alongside a 40s style “boogie-woogie” reminiscent of famous World War 2 tune, “The Bugle Boy from Company B.” This upbeat pop countdown is followed by a shower of human limbs from off-stage, each bucketful of body parts interrupting the Leading Player’s lyric insistence that “War is strict as Jesus”… “War is finer than Spring.” Which is all to say: not only that the “Glory” of kings and states amounts to butchery and bloodshed, but also that “entertainment” (not to mention religion) is far from innocent in this process. Keeping focused on what’s happening at center stage requires ignoring a background of brutality. The stage-sparkling smile functions as a smokescreen for massacre. At such moments the show brushes up against a Brechtian radicalism that critics have tended to miss [11].

And yet, despite its slick daring style and topical self-consciousness, when the show was originally produced in 1972, it may have looked in some ways strikingly conservative. The story of Pippin! reads like an allegory of Sixties rebellion destined to go awry, even a dismissal of political and existential passion altogether; it is a story of radicalization and inevitablede-radicalization. We begin with an angst-ridden young man leaving the educational establishment for which he has been groomed (Student Revolt?), proceeding to an expose of the horrors of war (Vietnam?), as well as the cruelty and callousness of paternal war-mongers (Johnson and Nixon?). We then proceed quickly to an overwhelming and ultimately “meaningless” experiment with drugs and free love (Hippie Counterculture?), followed by a sudden fall into “revolutionary” politics and patricide (the New Left and SDS? [12]), motivated by sympathy with a distant peasant revolt (Vietnam again?). Yet the rebel-king Pippin is subsequently shown to have no solutions — indeed no cluewhat to do. Pippin lacks not only wisdom but courage, too: within minutes of taking power he has abandoned the egalitarian phrases he spoke so passionately and is wishing aloud for the return of the king he himself killed — a wish that the LP instantly grants.

In a way, Pippin’s opposition to the Establishment is shown to be a kind of pseudo-opposition, less programmatic than symptomatic. Freed by the resurrected tyrant to devote himself to what now seems an increasingly farcical pursuit of Meaning, Pippin tries a few other things until he ends up totally spent. Collapsed by the side of the road, he is nursed back to health and recruited into domestic ordinariness, and household labors, a final existential rut from which the possibility of a spectacular public immolation now appears (however briefly) as the last chance at Ultimate Fulfillment. (Interestingly, the suicidal turn to spectacular self-immolation is shown to emerge as the last field of “transcendence,” and of “eternity,” once the realm of Science, Politics, Art, Religion, and the Flesh are shown to be exhausted. Once the vision of a life with enduring Meaning is dashed, the dream of instantaneous Celebrity and Sensational “perfect” Death seeps into its place, universal visibility effectively substituting for universal truth. If the true path cannot be known, one can at least make oneself known to others through a bright and shining stunt.) That is, until Pippin’s knees buckle and he says “No!” and the “everyday, ordinary” Catherine, comes to the rescue, saving him from not just the Players, but, arguably, from the dead-end quest for transcendence he’s been on for the past two hours. In the show’s closing moments, Pippin stands, stripped down by the Players whose Grand Finale he has refused, virtually naked beside Catherine and her son Theo. [13] Accepting (however ambivalently) a bare world without dreams of Meaning, he takes his place in quotidian existence without makeup or costumes, colored lights or even music to sing to. [14]

“Ordinary” Romantic Partnership is depicted finally as the last bulwark against the deadly drive of the Spectacle. But also as the only relief from the pursuit of “extraordinary” dreams; coupling appears here as they sole remaining site of Meaning in a world where all other realms have been found wanting. In a sense, Pippin chooses (or is compelled to “choose”) Domesticity=Obscurity=> Life over Publicity=Eternity=> Death.

But, of course, this binary opposition,which compels all but the true sadists to side with Innocence against Corruption, is itself far from innocent; it is itself the sign of a kind of counter-revolutionary sleight of hand. As if the pursuit of Meaning inevitably led to the fire pit, and the only way to avoid such a death trap was to stick to the Mundane. As if Pippin’s prior attempts to find a higher calling were inherently flawed; as if the solution is to give up on those world-changing realms, instead of—to nod Beckett’s way (or Mao’s) — try again, fail again, fail better. In this sense, the Player-troupe’s closing accusations — “Compromiser! Compromiser!" — hurled at Pippin after he refuses self-immolation, might be aimed at Stephen Schwartz himself, who was in 1968 or so already preparing the way for the counter-revolution, even before the high tide of the Sixties broke.

II: The Question of the Ending: Generations and Regeneration

But to be fair, Pippin! – at least in its revived form — does not abolish the pursuit of passion and meaning altogether. We must consider consider the “new” revised ending of the musical. [15] The essence of the revision is that after Pippin and Catherine (and Theo) are chastised, fired, and stripped of stage-dressing by the Leading Player, before the curtain falls on this frightened family (as it does in the original), the couple head off-stage, leaving Theo, Catherine’s (and now effectively Pippin’s) son, to double back to center stage. From here, the boy sings an a capella version of the chorus of Pippin’s opening number “Corner of the Sky,” signaling that — just as Pippin’s voyage ends — the young Theo’s own quest for Meaning and Belonging is about to begin. Cued by the youthful tune, the Leading Player and company slink back on stage, bringing with them music and spotlights, seizing on the prospect of a new dreamer to seduce. The new couple’s victory over the suicidal spectacle thus proves Pyrrhic. Just as Pippin and Catherine are committing themselves to an “ordinary” life (household chores, family duties, a regular sex routine, having children of their own) the specter of the “extraordinary” creeps in the back door. Hardly has the make-up been wiped away than the boy goes looking for Magic. [16] Theo’s curious hands explore the ruined remains of the set, like Jack at the base of some shadowy bean-stalk.

There are several ways that one can read this revised ending. Most obviously, it detaches the search for the “corner of the sky” from the character of Pippin. What is at stake here, the revised ending insists, is not merely individual matter, nor is it the condition of some isolated or peculiar historical example; rather it is something more pervasive, if not “universal.” (Nor can it be seen as something that “runs in the family,” as Theo is not of Pippin’s blood-line.) Pippin becomes a representative example, not a unique and rare case.

Building on this basic point, we can then read the new ending as reframing the Pippin-esque search for a “corner of the sky” as an essential feature of “Youth,” as a kind of undoubtedly dangerous, but perhaps necessary, inevitable, or even “natural” part of “growing up.” Something that every child—or at least every boy? — must inevitably go through. The fact that the Leading Player and company are now after the young Theo disturbs (after all, we now know, these “players” are out not to cultivate young talent, but to exploit and set fire to it for the sake of their own glory) yet also soothes (after all, it’s only natural, “boys will be boys”).

Either way, the spontaneous interpretation that most viewers will take away is likely something like: Pippin’s rebellion is kids’ stuff. From which it follows that: A) It is not stuff for adults — except insofar as they slip back into childishness, or never “grew up” in the first place; B) We should recognize that it’s “ok” and perfectly “normal” for kids to go through a stage (or two or three stages) of exploration and/or existential despair; C) We must be ever protective of our vulnerable and naïve children who may be seduced by all sorts of alluring but ultimately pointless or even self-destructive fantasies about having their lives “mean” something; D) We should take heart that those little Pippins out there will come round to “ordinary” life, so long as we remain vigilant. [17] More dialectically, we might in fact read this search for Meaning — with all its tragic, farcical ultimate futility — as not just a threat to the settlement of “ordinary” family life, but ultimately produced by it, that is, by the closure of dominant social relations, here exemplified by the establishment of the heterosexual, home and farm-owning couple. The establishment of the family coincides with — perhaps even founds — the desire to seek life beyond its bounds.

We should note, however, that the status of Catherine’s “estate” is very much in doubt at show’s end. Though never explicitly mentioned, it seems likely that her farm and household are taken away by the Leading Player, as part of the set that he strips from them, in retaliation for their rebellion. In fact, these upper-middle class trappings were never hers in the first place. [18] Careful viewers of the revival will have noticed that the actor playing (the player playing) Catherine, before her entrance as Catherine midway through Act Two, appears in the show earlier, as a kind of clownishly attired stage-hand, a marginalized member of the troupe. Not featured in the tricks and the dances of the rest of the players, the player-who-will-play-Catherine is confined to menial duties, clearing the stage for scene changes, dragging off-stage the heavy wooden chest that contains the decapitated head of the Visigoth who helps to puncture Pippin’s view of war after the number “Glory.” As the stage-hand performs such “backstage” and un-glorified tasks, moreover, she catches brief but significant up-close-glimpses of some of Pippin’s most vulnerable moments. She sees him quivering after the battle and after the overwhelming S&M orgy alike. Her final union with Pippin thus enacts a kind of symbolic union of stage-hand and stage-star, as both recognize and rebel against their disposable status with the killing machine of the spectacle.

Thus, whereas earlier productions of Pippin! that I’ve encountered (both through video and on-stage, whether using the “new” ending of the “old” one) have tended to suggest — through staging and posture — that Pippin and Catherine have some sort of “home base” to retreat to, the ending of the recent revival takes a distinct turn. Not only do they wander off, into the obscurity and invisibility of the exposed staged wings, but the precarious class position of Catherine is foregrounded if not altogether changed. Holding hands and stripped down they seem more homeless than homeward-bound. The ending reminds of the closure of Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (and other Chaplin films) where the Tramp and the Gamin walk off into the distance, hand-in-hand, “happy” to have found one another, but still without a clear place or prospect in the world. No longer alone, but still alienated from the society that offers them only the street to live in.

More than just an arbitrary directorial choice, the stripped down exit of the couple — as opposed to the on-stage curtain drop in the original version — in a way expresses the changed historical conditions of our contemporary historical moment with respect to the post-60s moment out of which the show emerged. In 1968, or even 1972, for most (white) Americans it was still possible to imagine a retreat for big and liberating dreams to something like stable middle class life. Not so any longer. For Pippin to refuse his role as (bright-burning) “Star” and for Catherine (or more precisely, the desperate hired player playing this role) to give up her precarious position as stage-hand and player is not to to return from dreams to the bedrock of Family and Property. Rather it is to ambivalently and anxiously embrace the unknowns of unemployment, homelessness, and poverty.

All the more reason to identify with Theo, as Pippin and Catherine head into the unknown. Theo here may come to represent not just the inevitability of the child’s (ultimately fruitless) exploration, but that “inner child” we are all rumored to have somewhere inside of us. The “generation gap” then can be read not only as a stage that will pass, but a stage that stays with us, a stage which always beckons our return, a stage that does not separate “generations” but destabilizes them, inhering within each “generation” or even within each subject or psyche, as a tension thatgenerates and regenerates, with each new earth-binding giving rise to yet another dream of flight. And yet, mediating against this more utopian potential [19] is the staging of the new ending, which is undoubtedly sinister — an entranced Theo is hoisted high, alone, stranded on a trapeze, under which the Leading Player gathers his shadowy troupe like so many salivating wolves. While Theo musically repeats Pippin’s sky-cornered anthem, it is a repetition with a difference: the quest for post-adolescent transcendence is now coded as a set-up, a trap for pre-pubescent innocence. Who would encourage their child to mingle with such fantasies?

III: Theoretical/Polemical Interlude On Precarious and Cynical Subjectivity Today

It’s one of the key provocative hypotheses of Louis Althusser: Ideology is objective, a matter of and a product of what we do, not just what we say or what we tell ourselves (though of course saying too remains a kind of doing). As he takes it up from Pascal, reversing the common sense of cause and effect: ‘You kneel down in church… and thus you believe.’ Belief here is understood more as a matter more of practices than of asserted or affirmed propositions, a matter of institutions interpellating subjects, rather than individuals freely choosing beliefs and subsequently acting upon them. Actions speak louder than words here, and, in fact, largely determine which words subjects end up speaking.

From very few of us these days does the present imperialist-capitalist system require anything like sincere belief in what we are doing, when we do it. (If it ever did.) It requires only objective, not subjective belief. It demands only that we continue to act as if we believe, that we keep our objections to ourselves, or that we vent them in private, where they can’t disrupt necessary operations.

So long as we continue to do as we are told, acting just as we would do if we did in fact believe, we can “feel” and “think” in any way we please. (Even billionaire bulldozer Mayor Bloomberg never asked Occupy Wall Street to change its mind, or even to stop dissenting, but simply to remove its expression of dissent from where it could disrupt business, from where it could be seen by others. It was not their minds or ideas, but only their bodies he objected to — perhaps also their bullhorns. This then provides a rather dark riposte to Occupy’s catchy and inspiring declaration that “You Can’t Evict an Idea.” ‘Go ahead and keep your Ideas,’ Bloomberg Co. reply, ‘All that we demand is the removal of your bodies.’) We can be communists or anarchists in our hearts, so long as we are compliant in our habits.

So you are allowed to whine while you pay your taxes. To cry after you shoot the Iraqi man who, as it turned out, was only carrying a camera. Even to laugh out loud at American political hypocrisy while sitting on the couch at home (Stephen Colbert or Jon Stewart anyone?) so long as when you’re in public at a sporting event, you damn well respect that flag with your straight legs locked; no folded knees will be tolerated. You don’t need to sing along, or to hold your hand over your chest, but you’d best not sit.

But of course, it’s hard to maintain beliefs for which there seems no proper place. “Going through the motions” for long enough has a way of chiseling out belief that fits the prescribed course of action. The objective (actions) has a way of framing/constraining the subjective (consciousness). People tend to be uncomfortable with the disconnect between subjective statements of what they “really believe” and what they and others see them(selves) actuallydoing on a day-to-day basis. How can you sustain subjectively a belief that things really ought to otherwise, when, each day, your waking hours are devoted to keeping things going as they are? Belief that things ought to be otherwise requires some sort of earthly support. [20] The absence of alternatives, lived long enough as “reality,” tends to become a felt argument for keeping things as they are.

This then would be the flip side of Althusser’s notion of ideology (one pursued in a way by Alain Badiou): that the sustenance of belief (the Subject of a Truth Process that keeps fidelity to an Event in Badiou’s parlance) requires the construction of an objective support for that belief. [21] Just as ideological state apparatuses offer the practices that interpellate individuals as Subjects of a ruling order, so sustaining the Idea that things ought to be otherwise than they are demands something like the building of new organization, new institutions, new practices, new communities, new modes of embodying that Idea in the world. [22]

But what I wanted to get at here is not just that the system does not require us to believe in the jobs we are doing; it may not even want us to believe in them. Or to put it in less conspiratorial language: the system’s own impersonal reproduction may depend upon most of us not really believing in what we are doing — even as it may extract (cynical) pledges from us to the effect that “we believe” in what we are doing. (Such forced pledges merely raise the cynicism to an even higher level.) Better fleshy robots going through the motions than professionals finding meaning in their work. The system can make do with cynics; it may even operate more smoothly with them at the controls.

For what happens when subjects really act as if they believe seriously in the things we are taught to “believe” cynically? When a doctor really, fully takes her Hippocratic oath to heart? When she truly refuses to do harm, or to turn away any patient in need, regardless of legal status, or the ability to pay? What happens when healers (nurses, doctors, nurse practitioners, physician’s assistants…) fully identify with the social roles they have been apportioned? When they refuse to limit their commitment to the job description and the contract?

Similarly with teachers. What happens when we take our allotted role truly to heart, when we identify fully with the structural position we are so precariously and contingently granted — that we have trained and studied and practiced for — as more than just a job, but as a passion, a vocation, a mission? If and when we are faithful and give ourselves fully to the mission of educating others, is there not a disruptive, radical, even a revolutionary potential? For the mission here becomes not just to teach those who can afford to enroll, or who happen to be placed in our allotted classrooms, but to teach. Period. To teach whoever shows up. And not only that. To show up and teach, wherever teaching needs to be done, wherever teachers are needed. Wherever learning is wanted and wanting. Not just to deliver certain skills, or meet certain minimum requirements, but to help that truth to flow which the times demand. To serve the people. Radical education scholar-activist Henry Giroux hits at something similar when he calls for a “borderless pedagogy” one that “crosses zones of knowledge control and policing and aims to democratize power and knowledge.” [23]

All of which is to say, to fully identify with and to give of oneself to the mission as more than a “job” is to at least create the potential for a disruptive excess that may create friction for, even jam the works of, the existing system. (At most, in certain cases where human need is central, it is to create a fleeting glimpse of something like communism, a mode of life where abilities are fully engaged and needs put front and center, as ends in themselves.) [24] Which is also to say that the contemporary system does not really want, cannot really afford, to be creating doctors or teachers or fill-in-the-blank-here that fully commit to and identify with their work. It needs us to keep our distance from who we are and what we do, from our students or patients, from our own avowed ethics, from ourselves, and others. It needs split, cynical, if not schizophrenic, subjects. It wants us to treat the work we do as “just a job,” not a vocation, to treat our work as means to ‘making a living’ not an integral part of our actual Life Project… even while demanding and expecting more and more work-time and work-availability from us. [25]

Henry Giroux

Let us ask a radical cluster of naïve questions: What would happen if all doctors refused to not heal? All teachers to not be teach? If we refused to confine our commitments in terms of time and place? If we refused to “punch out” or “go home”? If we refused to accept the orders of bosses who would tell us when to “start” and when to “quit”? If we fully occupied the positions that we are encouraged to take up only cynically and provisionally?

The cynical attitude of treating oneself (and others) as temporary, of refusing to fully assume the standpoint of the work we are doing, (and the relationships we are creating and inhabiting), seems to me to be exactly what this deformed system needs to keep going as is. (One thing of many, to be sure.) What if we shed the cynical shell? What if we refused the position of resigned distance and fully assumed our responsibilities and relations where we are? If we took the system at its word about the “value of teaching” and the “duty of the healer” and the “value of the artist” and the “importance of education” …all that noble liberal bullshit? What happens when the craft-worker refuses to abandon her claim to craft? When the subject refuses to give up on his/her commitment to Truth: whether in the realm of Science, Art, Politics…Or Love? [26]

What if we refused this ideology of deferral, predicated as it is on always taking a certain distance from our present, from what we are actually doing, and what is actually happening around us? What if we refused to be cynical and instead gave in — or pretended to give in — to a naïve position that takes the “progressive” proclamations of the system at their word? What if we refused to take ‘the proper distance’ from our present, from ourselves, and from others?

Of course, such disassociation of people from their work, and from one another, is not a strictly subjective phenomenon. Far from it; the alienation is built into the structures of the system — a product of history. For years critics and commentators have been tracking the rise in worker precarity and the growth of the “perma-temp” economy. Sub-subsistence wages and contrived part-time schedules (designed to deny workers benefits, as well as to maintain employer leverage with respect to employees) compel workers to take two or three jobs to meet expenses, while rising levels of structural unemployment make people afraid to speak up, strike out, let alone organize, for fear of losing their jobs. The grievances are familiar and the basic trends well known. Taylorism was never just about speeding up production and raising efficiency, but about breaking the identification of skilled workers with their work, and thus smashing the power that such collective pride, authority, knowledge, and dignity gave rise to. As Harry Braverman puts it in his classic work Labor and Monopoly Capital, it was about “degrading” work, separating workers from the fullness of their own labor, and from their potential revolutionary subject position as the living-thinking force in the heart of the capitalist machine.[27])

What may not yet have taken root in our common sense, however, is what these trends mean for the subjective relationship to work and to particular workplaces or particular jobs (and what this in turn means for engaging and transforming consciousness, as well as for developing political thinking and radical strategy). Beyond the quantitative measures of wages or benefits or the hours of travel and sleep deprivation, what does working as a “temp” for extended periods do to one’s sense of one’s labors, one’s identity, and one’s relationship to other workers? What does viewing oneself as employed in a particular profession ‘only for the moment’ (for instance, as a contingent faculty member) do to one’s social and psychological (and thus potentially political) relationship to one’s labor and to the institution(s) in which one works? [28]

…And what, if anything, could any of this have to do with Pippin!?

IV: Allegory of Cynical Submission… or of Subversive Sincerity? (ENTER: CATHERINE)

It turns out that much depends on the seemingly innocuous character of Catherine.

In my early encounters with the musical, she always seemed the show’s most boring figure. But in fact, Catherine may just be the closest thing to a real hero that we get. [29] Played right, she is the most courageous and determined character, as well as the bearer of perhaps the show’s most important and timely message. That message is something like this: holding fast to your desire, fully assuming the role you are (however contingently) given, becoming sincere in a cynical world, might just tear that world asunder…. An abused but passionate subject can help bring down the entire (homicidal, suicidal) spectacular apparatus.

For Catherine is not in fact boring, she is a character who has been hired to play boring. Forced to play boring. Even before her entrance as Catherine (which happens midway through in Act Two), she is presented as a kind of precariously employed troupe member, doing the shit work so that others can dance and sing. Nor is she at ease once she enters in her official role, performing the cliché she has been hired to play. Her opening song, “Everyday Kind of Woman,” conjures and mocks the romantic stereotype of the “everyday unassuming kind woman,” whom is nonetheless coded in such a way as to let all viewing her know from the get-go that she is destined to be the “true love” for whatever lucky man has just crossed her path. The lyrics of her song — and to some extent even the song’s rather unremarkable melody — emphasize her “commonplace” quality, even as the ensemble choreography that casts the rest of the players as cherubs and handmaidens to her angel sends a very different message. She announces herself — with the players’ help — as the “every day kind of woman” with whom you are destined to fall almost instantly in love. [30] Later, once she revives Pippin to some degree of consciousness (and lust), Catherine turns to nagging the new arrival to get more involved with the household duties around the estate, and to take more of an interest in her son, Theo (particularly after his pet duck dies). [31] She delivers the lines of a familiar female stereotype.

But though hired to play that unsuspecting, irresistible, unsustainable combination of nourishing nag — her role in the plot is to nurse Pippin back to health, but then to drive him away, back to the Players — Catherine never seems to quite have her (cliché burdened) act together. She’s late for her opening-entrance, requiring three orchestra-accompanied announcements from the Leading Player before finding her way through the curtains, and even then she comes on stage complaining about the trouble she’s been having with her false eyelashes. She stumbles over several of her lines, speaks in an affected tone, and at one point draws harsh words and cold stares from the Leading Player when she fails to deliver a crucial speech “naggingly” enough. The LP threatens her job, pointing out her disposability as an aging actress. More than any other figure, (with the exception of the LP) Catherine is the character who shows us — unwittingly, it would seem — that she is playing a role, a role in the process of breaking down.

Not that she isn’t trying.

Indeed, Catherine’s other main feature is that she tries too hard. And this is where it gets interesting. She tries so hard, despite or perhaps in part because of her early missteps, so hard that she starts in a sense to actually become (like) the character she is playing. She moves from playing the short-lived love interest to actually falling in love. She comes to fully assume the role that she is simply supposed to play. Under threat of replacement — and unemployment — at the hands of the LP, whose cold glare and harsh words reveal the malevolent side of this smiling show-master—her heart gambles on Pippin, though doing so makes her even more vulnerable (on two fronts, as it were). In a sense, her precarity gives rise to her passionate commitment. Catherine here enacts a kind of solidarity of the disposable: an alliance of the stage-hand and the star, as the spectacle is shown to be as indifferent to the life of the one as to the other. Passionately identifying with her role—taking it all the way—(the actor playing) Catherine subverts the entire homicidal project that has recruited her (and provisionally empowered her) in the first place. She breaks from the script, stands up to the LP, derails the plot, even forcing the orchestra to add a song to the program after Pippin takes off for one last shot at glory (“I Guess I’ll Miss the Man”). Finally, she interrupts and helps Pippin to wreck “The Finale,” forcing herself where she doesn’t officially belong.

This is to say (to connect back to the preceding section): the threat to the reproduction of the system lies not only with those who refuse to be interpellated by the ideological state apparatuses (aka the “Bad Subjects”), but with those who hold too tight and sincerely (even “naively”) to the identity or function into which the system recruits them, subjects who fail to internalize the proper distance from the roles and doctrines which they are expected to enact and to uphold (but not, really to believe in). Catherine: call her the Too Good Subject. Where Pippin’s search for the extraordinary is shown to drive him into cross-hairs of a murderous spectacle, Catherine’s passionate commitment to the ordinary is shown to offer means to disrupt that spectacle utterly.

Of course, before we make of Catherine an unsung radical hero, we need to also note a rather large irony and tension: namely that the subversive passion allowed in the show is one that is geared towards love (and perhaps marriage), towards in a sense capturing/saving Pippin from his own passionate dreams of “extraordinariness.” Similarly, as the show is often produced, it isn’t entirely clear that, for Pippin, choosing Catherine represents a positive alternative, so much as the exhaustion of available possibilities for transcendence. (The “negation of negation” not necessarily amounting to an affirmation.) Does Pippin’s decision to refuse death and glory come from recognizing a true love for Catherine (or Theo), or does he merely come to… settle? Interestingly, on this question of the status of Pippin’s final settling down we find a small but significant difference between the original production and the recent revival. [32] “I think it was here,” Pippin sings in the original version, a cappella, the keyboardist and orchestra ordered into final silence, “’Cuz it never was there.” He derives a speculative, hypothetical presence from an experienced absence. The recent revival, however, rewrites this line in a way that would veil its continuing existential uncertainty (and anxiety), with Pippin singing that “It always was here… It never was there,” as if Pippin had “known all along” that it was domesticity, love, and family that he was after, as if he need never have taken his two-hour voyage in the first place!

Certainly there is some truth in Pippin’s recognition that “I’m not a river, or a giant bird, soars to the sea….and if I’m never tied to anything, I’ll never be free.” There is an important point here, a refutation of certain negative, abstract, individualist notions of “complete freedom” or “autonomy” or “escape” from dominant society…But the show’s insinuation that the only “thing” that one can “tie oneself” to is a certain notion of heteronormative family life, “home, woman and child,” is surely far from innocent. Similarly, his follow-up line that “I wanted magic shows and miracles, a shining parade…But there’s no color I could have on earth that won’t finally fade,” is another obvious truth; however this basic recognition of mortality still begs the question of how one ought best to spend one’s (limited, soon-to-fade) time in color on earth. The closing ideology comes through in the implication that “all that’s left” once one gives up on dreams of flight and color is a turn to the particular drab ground of heteronormative domesticity.

But again, as noted above, the question of the status of Catherine’s farm-estate within the context of this show-within-a-show becomes material. Is it stripped away along with the make-up, lights, music, and background set? It seems plausible to assume so, though it’s not made explicit. If so, then Pippin (and Catherine’s) choice cannot be read as a turn to petty bourgeois security (family, religion, property, etc.), but rather represents a much more bleak, uncertain facing of the unknown. It amounts to a more radical act—a choice of precarious and vulnerable lifetogether, rather than either a glorious (suicidal) spectacular death or a cynical (homicidal) playing along at the expense of others. A negation of the death-craving spectacle without a positive affirmation to fall back on. A facing of the abyss with another, rather than continuing on with a system of deceit and the murderous exploitation of dreams and dreamers.

Is Pippin — or Catherine for that matter — choosing Something, or simply refusing Nothing? Is his turn to Love a victory or a retreat? The grasping hold of a truth — albeit one stumbled upon — or a resignation? A settling for what’s left or for what’s ‘realistic’ after dreams are done and ideals go up in smoke, or a charting of new ground upon which new dreams might emerge, on firmer and non-individualist ground? What may be most intriguing about the end of Pippin! is that it’s so difficult to answer these questions. Love looks an awful like resignation here, like a fearful retreat. A more satisfying synthesis of the ordinary and the extraordinary eludes us. Is it possible to bring together the immediacy of personal love and, the abstraction of eternal truth? At least for Pippin! on the spectacular stage, it is not.

And yet the contortions through which this show must go to send passion packing in the wings can’t but speak to the continued possibility of more grounded and exalted dreams.

Footnotes

- The production was developed at the A.R.T. in Cambridge, under the direction of Diane Paulus.

- Brantley does, however, single out Andre Martin’s show-stopping performance as Berthe, as well as Rachel Bay Jones’ portrayal of Catherine (whom we will return to below): “Rachel Bay Jones is Catherine, the young widow (and the not-so-young actress who plays her), who sets her cap at Pippin in the second act. She gives heart to the show-within-the-show shtick, and she creates a two-level character that you root for and care about.” Rachel Bay Jones’ performance was indeed outstanding. See Ben Brantley’s New York Times review of April 25, 2103, “The Old Razzle Dazzle, Fit for a Prince” and Clive Barnes’ Times review of “Musical: Pippin! And the Imperial,” Oct. 24, 1972.

- Interestingly the Boston Globe’s Jeffrey Gantz lauds the production for its “refreshing lack of cynicism.” One wonders if it is the production or Brantley himself who is the cynic!

- Though indeed the current ART to Broadway production, with its astounding troupe of circus acrobats and magic tricks does indeed far exceed the original in its sheer apparatus of athletic entertainment. As of this writing, the A.R.T. In Cambridge, where the current revival of Pippin! originated, has continued the special effects trend with its most recent production of The Tempest, where the spectacle of Teller’s magic tricks tended to steal the show — and the critical bite — from Shakespeare’s allegory of colonial rule and rebellion.

- This is assuming that even these “barbarians” could not be made friends by the new revolutionary peasant state!

- Relevant here was the choice of Pippin’s haircut: the A.R.T. production in Boston opted to give Pippin not long and flowing almost Byronic golden locks of the original production, but rather a bowl cut with a cowlick standing straight up on the back of his head, reminiscent not of a wayward prince but of Alfalfa from The Little Rascals. This seemingly small costume choice was significant: From the moment of his appearance, Pippin’s presence-power was undercut — however much his voice may soar — a certain foolishness foregrounded. It is made clear to us that Pippin doesn’t quite have his act together, not only in the ways he proclaims, but in other ways as well. Our crusader for Life and Meaning cannot even keep his hair properly combed. The Alfalfa hair becomes a spike to puncture audience identification. The Broadway Music Box production thankfully dispensed with this particular bit of costume-foolery.

- Adding another layer of irony here is the fact that the assassination opportunity at Arles is effectively set up by the scheming stepmother Fastrada (originally played by Chita Rivera) who hopes to manipulate the conflict between Pippin and Charlemagne to forward her own son’s Lewis chance at the throne. Thus Pippin’s political passion is shown to be doubly naïve, manipulated from multiple sides at once. His idealism is shown to be exploitable cover for a much more cynical and incestuous realpolitik.

- Though apparently none of the major songs from the student production ultimately made it into the Broadway version.

- The explanation for the failure of each vocational quickie gives Pippin a chance to cross the fourth wall and zing both State and Church. Regarding Art: “When the king makes budget cuts…the arts are the first to go!” For Religion: “I thought I’d been touched by an angel….that was no angel who touched me!”

- This early cast performance can be found here. See “Glory” from 27 minutes in.

- This particular moment in the show also carries a Benjaminian resonance: “culture” being shown to depend upon and to mask “barbarism.”

- One contemporary performance, available online, shows Ben Vereen sporting a black beret and pumping a as a member of Pippin’s short-lived “revolutionary” circle. (Fear of reprisal makes the group scatter, leaving Pippin to take action by himself.)

- One of Pippin’s final lines, sung a capella after the Players strip the stage of “magic” speaks to the regrounding here, a direct negation of Pippin’s inspiring opening images in “Corner of the Sky”: “I’m not a river, or a giant bird, that soars to the sea… If I’m never tied to anything, I’ll never be free.”

- “How do you feel, Pippin?” Catherine asks him in the original script. “Trapped,” Pippin replies. Adding one final frame-break to end the show, “Which isn’t a bad way to end a musical comedy.”

- According to Stephen Schwartz’s 2012 A.R.T. program note (“Some thoughts on Pippin as he turns 40”) this ending comes from a London Fringe production.

- Though at age ten or younger, Theo seems a bit young for the kind of Meaning that Pippin sets out for after Padua.

- Pippin and Catherine’s parental vigilance at this point is called into question, as they have wandered off-stage, leaving the boy behind.

- For a map of and reflection on the real foreclosures experienced by TV “Real Housewives” see:http://curbed.com/archives/2014/08/06/the-real-foreclosures-of-bravos-housewives.php

- A powerful articulation of the utopian figure of the child is rendered by Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, in“Toy Shop” (#146). As he engages the diary of Hebbel: “’A child [at the circus] seeing the tightrope-walkers singing, the pipers playing, the girls fetching water, the coachman driving, thinks all this is happening for the joy of doing so; he can’t imagine that these people have to eat and drink, go to bed and get up again. We however know what is at stake.’ Namely, earning a living, which commandeers all those activities as mere means, reduces them to mere interchangeable, abstract labour-time. The equivalent form marsall perceptions… Disenchantment with the contemplated world is the sensorium’s reaction to its objective role as a ‘commodity world.’… Children however are…still aware, in their spontaneous perception, of the contradiction between phenomenon and fungiility that the adult world no longer sees, and they shun it. Play is their defence. The unerring child is struck by the ‘peculiarity of the equivalent form': ‘use-value becomes the form of manifestation, the phenomenal form of its opposite, value.’ // In his purposeless activity the child, by a subterfuge, sides with use-value against exchange value.” (227-8) Also see his “Juvenal’s Error” (#134) in the same volume. (209-211) Verso: New York, 2000 edition.

- One could argue that providing such earthly support for the “other worldly” belief that things should be different than they are is one of the crucial tasks for true works of art in the world today.

- It’s worth emphasizing that for Badiou this support is not found in the world (as a kind of scientific discovery of the objective revolutionary force ‘already there’) so much as constructed, through a kind of hybrid process of weaving the Idea with the fibers of inherited reality.

- See for instance Badiou’s Theory of the Subject. Composed of Badiou’s seminars from 1975 to 1979, though first published in book form in in 1982, the Theory of the Subject makes a oddly appropriate counterpoint to Pippin!, a work similar emerged out of the end of the “Sixties,” to win the Tony Award in 1972. Both works, in their very different genres and radically opposed ways, are concerned with processing the historical experience of the post-1968 moment, and with coming to terms with the tension or contradiction of how to make meaning of one’s life in a world where all of the existing institutions and groups seem to be in some fundamental way lacking or compromised. Both works in their way offer “theories of the Subject” tracing the process by which individuals sustain or betray the exceptional Events that ruptures the everyday and “ordinariness” of their lives, holding forth or giving up on their desire to make of their animal lives something greater than themselves, something True, even something Immortal. Both works further trace this dynamic into the realm of politics as well as love, art as well as science (and philosophy). They are in many respects radically opposed.

- See Giroux’s recent book America’s Education Deficit and the War on Youth (Monthly Review Press, 2014). P. 26.

- It should be clear that such disruption should not be conceived of as an individualistic, or merely ethical matter (though certainly individuals and ethics have their role to play): the more collective and collaborative the disruptive excess, the better.

- Enter a major contradiction of capitalism: between quantitative and qualitative engagement here. How to get workers to “keep their distance” from their work even as they are expected to turn more and more of their lives over to those jobs?

- I am of course again thinking of Badiou here. See his Logics of Worlds, as well as his earlier and shorter book,Ethics. A similar point could be made for students. People in this culture are taught to speak highly of education as a kind of end in itself but are trained in many quarters from a young age to see education as a mere “means” to unrelated “ends”. Similarly that “end” of a “job” is also frequently understood as a sheer means…to the end of an income, a particular level of consumption, a level of economic security, the possibility of family life — family itself often framed as one more means to the end of having children, who can themselves function as human means to ends…. And so it goes…

- For a breathtakingly insightful treatment of the theme of Taylorism see Edmond Caldwell’s chapter “Time and Motion” found in his recent novel Human Wishes/Enemy Combatant. (Say It With Stones Press: 2011)

- How can one fully give oneself to one’s students or department when one has to rush off to teach on another campus? How can one come to fully identify with the ethos of one’s profession when one is forced to spend her time outside the profession, tending bar or waiting tables to make ends meet?

- And, as noted above, the recent revival has foregrounded her importance.

- Again underlining the ridiculousness of typical romance plots, in the original script, Catherine informs the audience that what first attracted her to Pippin above all the “arch of his foot.”

- Interestingly, in a Pascalian-Althusserian scene of intepellation, love between Pippin and Catherine is shown to begin blooming after Pippin cynically and disbelievingly gets down on his knees to pray alongside Theo for the health of his duck. The prayer fails, the duck dies, and yet going through the ritual is shown to have lasting material effects, on both the pray-er and the prayer stager/observer.

- I draw here from taking in the A.R.T. production in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in December, 2012.

- Interestingly, the original book here closes on a comic note, albeit one not without its own dark edge. “How do you feel, Pippin?” asks Catherine, the three of them stripped down to their underwear, beneath bare lights, at center stage, still facing the audience. After a pause, Pippin replies, “Trapped — which isn’t a bad way to end a musical comedy.”

Joseph G. Ramsey is a co-editor at Cultural Logic: an electronic journal of Marxist theory and practice, and a contributing board member at Socialism and Democracy.