The disenchantment of the world accomplished by the development of capitalism and modern science is a common enough theme in contemporary art and philosophy. Markets and colonialism have driven out the demons, gods, and spirits of the old world and given us a new one, now bathed in the aura of technological advancement. Or so the narrative goes. In the midst of this narrative of secularization, there are examples of new folkore, fantasy, and magic which resist the “iron cage” of bureaucratic rationalization. One such thread of re-enchantment concerns the discovery and popularization of dinosaurs.

As Jurassic World hits theaters, it is important for us to understand just what it is about these creatures that we find so appealing. Children are socialized into a love of dinosaurs from an early age. Committed fanboys militate against newer, more anatomically-correct renditions of the creatures which don them with the feathers that so many almost certainly sported. They inspire awe and fascination across cultures and social classes by connecting with the desire to see our own world as a magical place full of fantastic beings. In this sense, what is important for our analysis is not the “really-existing” dinosaurs, but how they are interpreted, imagined, and constructed in the popular imagination.

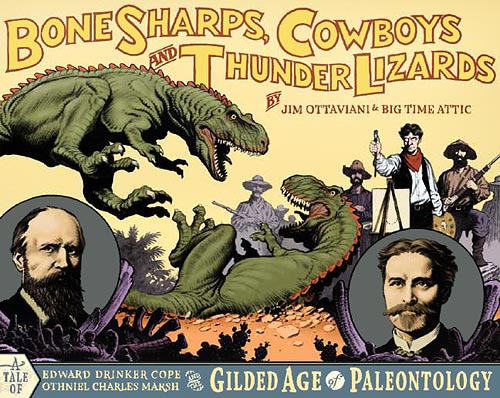

From the outset the creatures were identified with a romantic notion of the Old West, with the pioneering white male paleontologist setting out into the wilderness with nothing but his dreams and tools. The infamous “Bone Wars” or “Great Dinosaur Rush” saw competition between the infamous Cope and Marsh, who engaged in theft, sabotage, slander, and more in order to position themselves at the apogee of popular paleontology. This competition ruined their fortunes as well as numerous fossil discoveries and has gone down in history a cautionary tale of what happens when scientific research is pursued for private ends.

A scaled down version of this mythology is regularly employed by popular science programming which attempts to instill drama while downplaying those roots. In an updated fashion it was on display in one of the first scenes of the original Jurassic Park, which portrayed paleontologist Alan Grant as a more realistic version of Indiana Jones (complete with hat and desert setting). Coupled with real life events such as the “Sue” controversy, which saw the FBI and National Guard raiding the Black Hills Institute in order to seize Tyrannosaur fossils from the Sioux nation, these serve as a reminder that scientific advancements are not achieved in a vacuum, but rather are a site of social struggle. One does not discard the world of ideology, law, and power either in the field or in the laboratory.

Beyond the struggle over their excavation as fossils, the production of dinosaurs in the popular imagination has long been a terrain of contention. Today creationist museums provide an immersive encounter with Protestant ideologies which utilize dinosaurs to—bizarrely enough—“prove” the assertion that the world is a mere 6,000 years old. The imagery of carnivorous dinosaurs munching on plants while lounging in the Garden of Eden with Adam and Eve demonstrates the varied ways in which one can extract cultural rent from dinosaur lore to convey meaning.

Similarly dinosaurs are used to sell numerous commodities, spruce up over-the-top fantasy fiction, and mined to generate images of science fictional monstrosity. The power of their imagery stems from the long process of popularizing them as fantasy monsters from a forgotten age, exemplars of an enchanted Earth now transfigured by human intervention. In this manner they have often been employed in attempts to portray nature as a realm of barbarism and violence, particularly in their early instantiations as modernized dragons.

What is significant here is the ways in which the representation and popularization of dinosaurs constitutes a new modern lore. Often scientific developments do creep into the ever-growing products of popular culture, but it often takes the intervention of a popular cultural product for this to occur. The biggest example was of course Jurassic Park itself, which displaced the old conception of dinosaurs as lethargic, cold-blooded lizards by denoting the significance of their relationship to modern birds. The film’s production was aided by paleontologist Jack Horner, who gave credibility to the fantastic imagery of genetically-engineered modern dinosaurs running amok. Horner did advise director Steven Spielberg that most dinosaurs had feathers, but Spielberg reportedly replied, "Technicolor, feathers dinosaurs just aren't as scary." In fact, in Jurassic World, chief geneticist Dr. Henry Wu (reprising his role from the original film comments, "These aren't what dinosaurs actually looked like. These aren't natural!"

The original film led to a resurgence in dinosaur interest in the 1990s. Paleontologist Matthew Mossbrucker, director and chief curator of the Morrison Natural History Museum, claimed in a recent Washington Post article that, “There was a wonderful explosion of interest after the first movie. I really think it’s partially responsible for giving me a career.” This interplay between science and popular culture is an example of the vital conduits between the two that can be achieved by artistic productions. Speculative fiction has long served as an engine of imagination and concern for real world projects, from the development of instant messaging to 3D computers to all the projects of Elon Musk, described by some as a real world Tony Stark. The popular mythology of dinosaurs has served as a wellspring for funding, recruitment, and development of paleontology.

But at the risk of “geeking out” too much, let us take a moment to examine what it is that is compelling first about dinosaurs, and then about the new Jurassic World film. What is compelling is no mystery: these were real, sensuous beings that walked the very Earth we inhabit. They are not imagined extraterrestrials or products of folklore, they are in fact the descendants of contemporary animals. Nonetheless, they rose tens of feet in the air, measured at times over one hundred feet in length, inhabited a strange world with flying reptiles and marine reptiles that rivaled the size of our largest whales. For over one hundred million years they were the dominant life form of this planet, a fossilized testament if there ever was one that other worlds are very possible, even strange ones with sublime creatures that make our wildest fantasies seem dull and unimaginative. They are a testament to the wonder of nature, the very same nature that produced us and our consciousness which allows us to reflect back on evolutionary history.

This is the foundation for the popularity and ever-changing mythology of dinosaurs, a source of joy for young children and curious adults alike. It is what makes films like Jurassic World tick, but not without some artistic effort. One might be hard pressed to name dinosaur films outside of the Jurassic Park franchise that have been made in the last 20 years. Those that have been produced have been third rate, with poor CGI and atrocious stories. With the exception of the failed TV show Terra Nova (admittedly I’ve never seen Primeval) and the wonderful comic book series Age of Reptiles, these titans of popular imagination have only been given decent treatments in this one franchise.

But even in the Jurassic Park film series things have been complicated. The first film is widely recognized as a milestone of modern cinema, but its sequel The Lost World is at best remembered as a mixed bag. Chock-full of homages to old dinosaur films, including its namesake and King Kong, the film failed to capture the majesty of its predecessor. The third film in the franchise barely qualifies, even though it has its moments of great fun. It is tonally apart from the others and includes some over the top anthropomorphizations of the creatures.

So when a fourth film was announced most were rightly skeptical. After viewing the film, one cannot but conclude that those skepticisms were unfounded. Jurassic World delivers in every way one would hope for in a sequel to the original film, particularly in that it does not try to replicate that film's formula or mark itself as a newer, better version of the classic. The film is well-written and directed, with memorable dialogue and a compelling science fictional concept driving it. The prospect of a completed park in which humanity’s power over nature has become banal, leading to a decline in profits and a need to produce newer, more flashy products has led to the creation of a monstrosity: a designer dinosaur with the genetic material of multiple creatures culminating in a nearly unstoppable killing machine. The struggle to weaponize it and other creatures for defense contracts forms a sub-plot that will undoubtedly be utilized in any sequel.

Jurassic World captures the visual wonder of the original film, building on its foundation in ways that the other films failed to do. The setting itself assists in this effort, as this new park has been constructed on the island from the original film “Isla Nublar,” which is distinct from the “Isla Sorna” of the second and third films. Homages to the other films are subtle and seamlessly embedded in the film, along with a direct encounter with the old visitor’s center from the original film.

The old story of the impossibility of absolutely dominating nature is updated with the corollary: and we are the source of that impossibility. Humanity is a part of nature, as are its social structures, which form a context for this power and control. Elements of that social structure—in this case the profit motive and the power of market pressures—lead to imbalances in the perfect system, and finally a total collapse. If nothing else, the mode of domination of nature predicated upon market logic can only lead to disaster.

Jurassic World will hopefully have the same effect as the original film, of which it is a kind of direct sequel (it more or less ignores the events of the other two films). Perhaps with the upcoming Kong film Skull Island and new Godzilla films on the horizon, the creature feature is set to return as a major force in popular consciousness. Whatever the ultimate reception of the film (as of now it has secured the record for the highest opening of any film in history), dinosaur lore is undoubtedly here to stay.