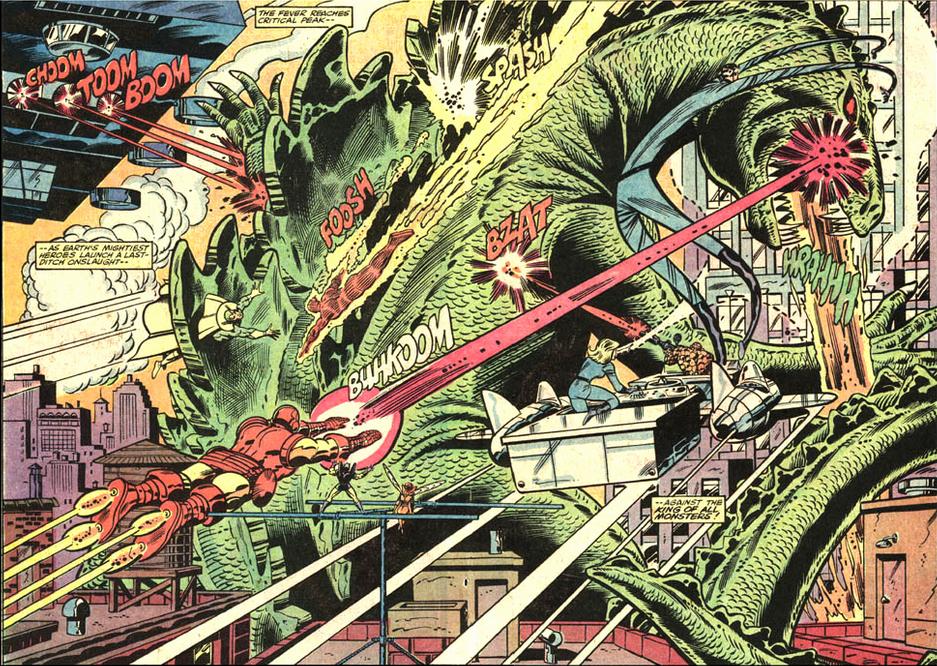

Marvel's original Godzilla series from the 1970s culminated in an epic battle with the Avengers. The series held the title of the longest running Godzilla comic book series until it was recently eclipsed by IDW's Godzilla Rulers of Earth series.

The advent of atomic weaponry in the 1940s forever changed the calculus of power between humanity and nature. In many ways nuclear power radicalized the metabolic rift between the productive apparatus of global capitalism and the biosphere by making the science fictional prospect of actual global warfare and radioactive fallout a hard reality. Coupled with the anxieties and red scares of this period, a culture of panic manifested itself with the advent of atomic horror films in the United States and the first kaiju films in Japan. The subject matter of writer Josh Finney’s independent graphic novel, World War Kaiju, reflects back on this time period by inverting the relationship between metaphor and its referents: what if the metaphors were the reality, and rather than waging war by means of atomic weapons the US and the USSR carried out an arms race of giant monster production?

The result is a dazzlingly humorous first volume to what promises to be a thoroughly beautiful series of graphic novels. Book One: the Cold War Years was released last fall, and I only got my hands on it a few weeks ago. As a fan of kaiju films, atomic horror, spy thrillers, and vintage science fiction, I cannot praise this book enough. Packed full of references and clever plays on genre tropes, it manages to produce something new in the kaiju genre by way of an under-utilized medium: the graphic novel.

Kaiju-themed graphic novels are few and far between. Marvel’s run at Godzilla in the 1970s produced a kind of parody of the Japanese creation (though seeing him take down a S.H.I.E.L.D. Helicarrier and battle the Avengers, as well as the absurd Devil Dinosaur, is enough to make one re-read the whole series), and subsequent treatments by Dark Horse and currently IDW have progressively improved in quality. There was a short run of Gamera comics, some excellent Gorgo comics illustrated by Steve Ditko, and the prequel graphic novels to both Pacific Rim and Godzilla put out by Legendary Pictures. Outside of manga, kaiju have had little representation in the medium beyond these big names.

That is why the use of a clever and original science fictional novum is so important for the artistic success of World War Kaiju. The prospect of literalizing metaphors allows for a critical reflection on the genre’s earliest social commentary without jeopardizing the comedic and light-hearted tone that makes the book so enjoyable. In the work (*mild spoilers ahead*) the US attack on Hiroshima is replaced by an attack on Tokyo (never mind the firebombing of Tokyo, this is a different timeline) using the “Fat Man” kaiju: a reptilian beast who is clearly an homage to Godzilla, and whose name is identical with that of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The Manhattan Project has succeeded in its attempts to split the atoms within a (fictional) KAI-235 isotope matrix. As explained by the in-universe documents in the back of the book, the result is a chain reaction in which matter self-arranges into a creature, whose brain is then synced up with a control system.

McEvoy's monochromatic style for the first pages gives way to an oversaturated technicolor as the story enters the reality of science fiction set in the 1960s.

Recalling the imagery of the 1954 Gojira, Patrick McEvoy’s artwork for the Tokyo attack is monochromatic, evoking not only images from the film but footage of World War II devastation as well. As the storyline moves forward into the 1960s, this template is displaced by an oversaturated technicolor reminiscent of the vibrant sf films that dominated that era. The story in Book One covers the period from 1945 up through the 1958 Formosa Straits Crisis and is told by way of a conversation set in the relative future (the 1970s it would seem) held between CIA agent Nick Hampton and journalist Keegan of Rolling Rock Magazine. References are made to a Third World War, which is teased by Finney to have been a consequence of the kaiju interventions in Vietnam. In an interview with Kyle Yount of the Kaijucast, Finney also mentioned that Book Two will culminate in the Cuban Monster Crisis, "When two beasts lay waste to an entire nation!"

References to popular culture and actual history are shot through the book. Eisenhower and Truman have important roles, as does the 1947 Roswell incident and the aforementioned political crises. The dramatic headline “Russia Has the Beast” recalls the panic across the United States that followed the Soviet Union’s development of nuclear technology, as well as the subsequent scapegoating of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. The younger version of Hampton is directly modeled on the look of American actor Nick Adams, who had roles in Rebel Without a Cause (Chick) and several kaiju films, including Invasion of Astro Monster and Frankenstein Conquers the World. The appearance of his counterpart in the Kaiju Science Taskforce is modeled on actor Akira Takarada, a star in numerous Toho films, including the original Godzilla.

Further references and historical encounters include Carl Sagan, J. Edgar Hoover, Prescott Bush, everything Mothra-related, Matango, old American cartoon shows, and much more. The style of humorous reference makes the book unintelligible for an audience without any historical knowledge or relationship to vintage science fiction (though one does not have to be a kaiju fan to enjoy it), but it nonetheless presents and enjoyable narrative with only a few deficiencies. For instance, the dialogue between Hampton and Keegan recycles the same form of, “You aren’t telling me enough,” “You can’t handle the truth…but here it is, bit by bit,” “Well you aren’t telling me enough!” and so on. The characters are tropes, imagery without flesh and blood, though it is hinted that an arc of development is underway for Hampton, whose views begin to evolve, ostensibly to justify his revelations to Keegan that dominate the narrative.

Literalized metaphors and stunning artwork make the novel more than worth support from general audiences seeking something beyond the normal Marvel and DC fare. Its 9 x 6 size is meant to recall the widescreen imagery of a movie theater, and the result is panels that exhibit a cinematic aura. A collaborative product of writer Josh Finney, artist Patrick McEvoy (who deftly traverses multiple aesthetic styles of comic book illustration), with contributions from Michael Colbert and editor Kat Rocha, World War Kaiju is a testament to what independent comic books can be. Furthermore, it breathes life into the struggling novums of the kaiju genre, allowing for critical reflection and politicization without a reversion to didactic methods of storytelling.

The book was financed by a Kickstarter project, and I would be remiss in my duties if I failed to mention their current Lovecraftian project Casefile: Arkham, whose Kickstarter project can be found here. Blending the detective/noir genres with the setting of H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos, the book promises to bring us to new heights of the Weird in visual form.