In spite of the torrential downpour of negativity from the established universe of Hollywood film critics, Neill Blomkamp and Terri Tatchell have accomplished another masterpiece of contemporary sf cinema in CHAPPiE. A tale of the inanimate becoming conscious, the film recalls the folkloric magic of Pinnochio set in a universe heavily influenced by Robocop. Hard science aficionados seeking the algorithms of consciousness will be sorely disappointed by the film’s flippant attitude to the mechanics of artificial intelligence beyond the basic distinction between strong and weak AI. Nonetheless, the purpose of art is not to instruct us in the facts of science, and the heart of science fiction is the exploration of the possibilities and consequences enacted by scientific principles rather than the mechanics of the principles themselves.

Co-writer Terri Tatchell (Blomkamp’s wife and co-writer of the Academy Award nominated District 9) explained that the film was constructed through a tension between her vision of a fairy tale and Blomkamp’s futuristic aesthetic. The product is a charming and powerful character—Chappie—inhabiting a near-future Johannesburg suffering from rapid tonal and class shifts. Chappie’s charm as a character—brilliantly brought to life by motion capture technology and actor Sharlto Copley’s performance—is that of an Oliver Twist-esque character exuding naiveté, innocence, and a kind of Edenic goodness in the midst of a cruel and cynical world.

The world-building of CHAPPiE has far more aesthetic than social texture. In Blomkamp’s previous installments in his self-styled spiritual “trilogy” (i.e. a trilogy not of one narrative or universe but maintaining a similar aesthetic) we have a strong sense of how the social order is related to their respective science fictional novums. The varied social responses to a sudden influx of unskilled alien labor in South Africa (District 9) and the complex dystopia of radical class oppression (Elysium) make a certain kind of sense that is wholly lacking in CHAPPiE’s near-contemporary Johannesburg. Abject criminality dominates the impoverished masses who are represented in a completely unsympathetic light, particularly in respect to the previous two films. The middle and upper classes are shown to be guardians of an amoral order that has no obvious purpose beyond stemming the tide of criminality by way of armies of robotic cops.

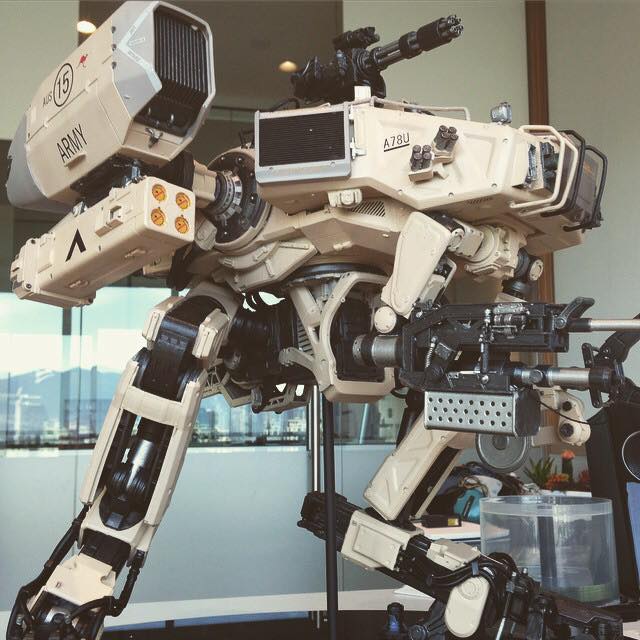

Transvaal Corporation comes to the rescue with its “scouts,” bipedal robots with a complex “weak AI” system who function as bullet-proof shock troops for militarized South African police. They are uniformly presented as heroic experiments with an astounding knack for bringing crime rates down. The Max Max world they combat is dominated by criminal gangsters—white and black—who are dominated by the aesthetics of zef, a lower middle/working class subculture among white Afrikaaners, represented by the rap-rave group Die Antwoord.

Die Antwoord is composed of the rappers Ninja and Yolandi Visser (or Vi$$er for those so inclined) who give powerful performances in the film. Yolandi explains zef as a subculture “associated with people who soup their cars up and rock gold and shit. Zef is, you’re poor but you’re fancy. You’re poor but you’re sexy, you’ve got style.” Their initial serious dialogues on screen are shaky and seem to portend a catastrophe of amateur acting for the rest of the film, but this is absolutely dispelled by the end of the first act. Indeed the performance of Yolandi in particular was an unexpected treat.

The idea of CHAPPiE was born from Blomkamp’s reveries while listening to Die Antwoord’s music. He absurdly imagined a child-like AI raised by the pair, coming to terms with its very being through the medium of this very outlandish style of self-presentation. Coupled with the gangster ethics of his futuristic Johannesburg, the couple establish a powerful dynamic that grows with the film and permits space for acts of heroism that truly tug at the heart. Ninja plays the Freudian role of “daddy,” extolling virtues of self-sufficiency, violence, and “coolness” in opposition to Yolandi’s “mommy” who encourages Chappie’s creativity, education, and uniqueness as a loved “black sheep.”

Without recounting the entirety of the film, Chappie is born of the work of Transvaal employee Deon (Dev Patel) who places the software in a battle-damaged scout. Deon and the disassembled robot are kidnapped by the couple and their sidekick Amerika (Jose Pablo Cantillo), who plan to force the robot to help them carry out a heist to pay off a particularly monstrous gangster. In the process, Chappie goes through a rapid period of socialization and identity-formation and is constantly pulled between “mommy,” “daddy,” and “maker” (Deon). He—and Chappie is socialized as a male, as “daddy” forces him to stop playing with dolls in order to become a proper gangster—undergoes a rapid series of crises in which he comes to understand that the world is an incredibly violent place.

As he comes to term with relationships, lying, and violence, Chappie establishes an ethic for himself that eschews violence. After several traumatizing scenes (for the viewer and Chappie himself), he commits to an ethic of non-violence and can only be deceived into engaging in violent acts later on. By the end of the film he performs near-religious feats of technical prowess and compassion that recall the Hugo Award nominated short story “For A Breath I Tarry” by Robert Zelazny (those we see the film and familiarize themselves with the end of the story will understand the similarities). The unexpected ending, which involves transformations and resurrections made possible by Chappie’s very existence, carries an enormous amount of weight and seals the comedic—in the sense of happy endings—nature of the film.

Coming on the back of the previous two films, CHAPPiE is indeed a comedy. Aside from the out and out humor—particularly the vocabulary choices of the geeky Deon and the non-swearing religious nut Vincent Moore (played by Hugh Jackman with full Australian accent)—the narrative arc is itself comedic, albeit quite dark and cynical. It recalls the sensibility of some works of absurdist theater, but with a grounding in the successful actions of ethical subjects. Indeed it is a thoughtful science fictional comedy that explores philosophical and ethical themes in much the same way that Elysium functions as a more thoughtful version of a traditional action/adventure film.

Critics are not without their points in regard to some aspects of the film. Aside from the politically-questionable world-building I cited before (and the unforgiveable, glaring lack of black characters in a film set in Johannesburg), there are a number of minor plot holes and blind spots that keep the narrative moving, yet ultimately leave the viewers scratching their heads with “Wait, why didn’t they just…” and “So why does nobody do anything about that, that seems like the kind of thing that authorities might frown upon…” and so on. Such narrative squabbles amount to nitpicking from the standpoint I am defending here, as do hard science critiques that to me seem sophomoric (really, seriously, if you expect an sf Hollywood film to answer your questions about the possibility of AI then you are simply using art for something it is not capable of).

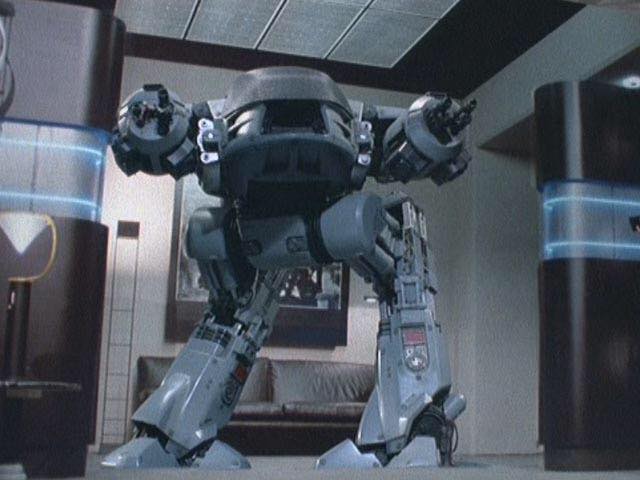

Character motivations are the weakest part of the film, and in that respect only for the role of the villainous Vincent Moore. Hugh Jackman’s performance is fantastic but lacks a clear motivation. Moore is angered that his MOOSE design is derided as “expensive overkill” in comparison to the tried and tested police scouts. The MOOSE design is an homage to ED-209, the “Enforcement Droid” of Robocop fame. It is controlled by a neural interface system, a product of Moore’s seemingly religious opposition to robotic sentience, and decked out with an absurd array of bombs, guns, and oversized hedge clippers.

His fundamentalist beliefs are embedded in his language but left undeveloped (though the imagery of him crossing himself right after a gangster crosses himself is a priceless gem in the film). Moore regards robot autonomy as an abomination and the scouts as an affront to the brilliance of his MOOSE system. In the end, the excesses of the robot and Moore’s character are put on full display without a clear sense of the why. Certainly people commit anti-social acts in the interests of opportunism and fundamental ideals, but it would be great to have a little more to it than sheer action.

On the topic of needing more, Tatchell noted in her Geeks Guide to the Galaxy interview that the character of Michelle Bradley would have been expanded had she known that Sigourney Weaver would have been secured for the role. Weaver’s brief appearances are meaningful and delightful to the eye of the science fiction geek, particularly in her line, “Burn it to ash” (a reference to Alien). Her encounters with Blomkamp on set sparked the conversation that has resulted in Fox greenlighting a revival of the Alien franchise (this time obliterating the timeline of movies following Aliens), the subject of an earlier post of mine.

To conclude, CHAPPiE is a fairy tale wrapped in a science fictional aesthetic. It is humorous and heart wrenching. Tatchell’s writing job focused primarily on the emotional exchanges of Chappie, and even hardened critics of the film cannot but express the emotional resonance of the character. Though a product of CGI, Blomkamp described that aspect as “2 million dollars’ worth of makeup” for Sharlto Copley’s performance, and it is a performance to be remembered. The weaknesses of the film are far outweighed by the emotional import of Chappie’s performance and the whole arc of belonging—to family, his maker, and the world—that propels the narrative. It is a fitting and heart wrenching end to Blomkamp’s “trilogy” and well worth your time. The weirdness of the film, far from being its weakness, is its strength.