A scene from Matthew Warchus' Pride.

The story of an encounter between a group of left-wing gay activists in London and a remote mining community in southern Wales would seem calculated to provoke applause from both crowds. It is rare enough these days to see a film that celebrates labor struggles. To have one that commemorates a moment of solidarity between the “old” cause of labor and gay rights, the movement that serves as a paradigm for “new social movements” based around identity rather than class, is practically a miracle. Pride shows that for a brief time in 1984 and 1985, gay activists and Welsh miners came together, and found that together they were greater than the sum of their parts.

Hence, it would surely be enough from a socialist standpoint to celebrate Pride as an inspiring story that should be remembered in a time of austerity and defeat for all social movements, labor and gay rights among them. Writers in many left-wing newspapers and websites have done this, and will likely continue.

But one worries that stopping there in fact gives Pride short shrift both as a work of art and a memorial to our common struggles. In an era where nostalgia is a dreary product of a left that cannot see beyond its past to turn toward the challenges that face it presently (see Ken Loach’s dreadful The Spirit of ’45), Pride shows us what is best and worst about the past. Moreover it does so in a way that seems to look forward as much as backward.

* * *

Pride is, of course, based on a true story, one that its writer long assumed no one would ever tell. As Margaret Thatcher vows to press on with her assault and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) totters under brutal repression by the police, a mass scabbing operation sponsored by the state, and the strain months-long strike has placed on their communities, the film shows a group of young and idealistic activists conceive the idea of a gay support group for the miners. “[The miners] are getting the same treatment that we get from the police everyday,” reasons Mark Ashton (Ben Schnetzer).

Facing a great deal of skepticism from its initial audience, Ashton and a group of six others constitute themselves as LGSM in a gay bookshop in Brixton, south London. They struggle at first to find an outlet for the donations they collect; their calls go unanswered or politely rebuffed by the NUM bureaucracy. Finally, they hit on the idea of going directly to the miners by cold-calling the union hall in the Welsh village of Onllwyn, reaching Dai (Paddy Considine), a union representative. The amiable Dai is in for some culture shock as he visits the club where LGSM hang out, but as he says to the audience: “When you’re up against a foe that’s bigger and stronger than anything you’ve ever seen, discovering you have a friend you knew nothing about is the best feeling in the world.”

Soon, LGSM’s stellar record in raising funds is taken notice of by the union support committee in Onllwyn. Dai and the more open minds on the committee insist that LGSM be invited to their village as the other support groups have been, and the stage is set for a clash of cultures, provoking many hilarious scenes. Two awkward young miners struggle between their visible discomfort at being confronted with such unambiguous examples of the gay lifestyle and their genuine admiration for Jonathan’s (Dominic West) dance moves. In the end they ask him for dancing lessons. An old miner’s wife asks Steph (Faye Marsay) in complete sincerity if it’s true that all lesbians are vegetarians, while another asks the gay couple nearest her “I never understood, in your kind of relationship, who does the housework?” (there’s a point in here somewhere about social reproduction, but I’m digressing.)

In fact, as a former LGSM leader reveals in an interview with Colin Wilson for rs21, the barriers between the LGSM and the mining community were even greater than what is portrayed in the film. While the film portrays a group of idealistic young gay activists with little mention of their background, the real-life activists in LGSM were seasoned leftists from the revolutionary Militant tendency in the Labour Party, the Socialist Workers’ Party, the youth league of the Communist Party and other left groups (the real-life Mark Ashton was a YCL activist). In addition, the settlements of the Dulais valley were Welsh-speaking, so the miners were encountering the London gay activists in their second language. It was a meeting of two entirely different worlds.

The comedic aspects of this culture clash — including the scene of mining wives shoving their way into a men-only London gay dance club and having the time of their lives, and which come across most forcefully in the trailer — would seem to paint the film as a comedy. It is, of course, but the deliberate foregrounding of comedy might lead some audiences to forget that this is the story of a defeat. The miners, of course, lost. (American audiences might miss out on the significance of this — the event that is the equivalent of their struggle in US labor history, PATCO’s strike in 1981 and Reagan’s unilateral firing of all striking air traffic controllers, has nowhere near the resonance in American culture that the miners’ struggle still has in Britain). Similarly, the mid-eighties were a grim period for the gay rights movement, when HIV-infected men were dropping like flies, and the consent age for gay sex in Britain remained 21 (it was 16 for the rest of the population).

It is the great merit of Pride that the defeat of the miners, and the dire proportions of the AIDS crisis, are neither ignored nor downplayed. It is the thorough attention paid to the defeats of both the miners and the gay movement which gives Pride a universal aspect, leading it far beyond the ground of mere leftist reminiscence.

* * *

The real-life LGSM had resolved that their support for the miners was unconditional, meaning that they would continue to raise funds and offer material aid “even if the miners had told [them] to fuck off.” Though it is not exactly true to the history, the end of the relationship between the miners of Onllwyn and LGSM is handled in an extremely deft way, showing concretely how the miners were weaker without LGSM, and vice versa.

The real-life LGSM, marching in the 1985 pride parade

Of course, it would be expecting too much — reasonable leftist advice to not essentialize the working class aside — for the miners to have immediately embraced gay solidarity. The ice is broken when Jonathan informs their welcome committee that the police have no right to arrest and detain pickets without a charge, prompting the irate miner’s wife Siân (Jessica Gunning) to march to the police station and lecture the cops on the pickets’ rights.

But the more progressive members of the community, including Dai and the wonderfully feisty Hefina (Imelda Staunton) have to wage a constant struggle against the prejudice built up by Welsh Calvinism and the centuries of isolation experienced by the mining villages. Though Hefina’s son offers Mark a pint, she has to march in and demand that he and his friends mingle with the activists. Mark’s speech to the miners falls flat when he declares that one-fifth of them must be gay, as is true for the general population. The safety of LGSM members is genuinely uncertain in an atmosphere of concealed and not-so-concealed bigotry from some miners, despite the valiant efforts of the more enlightened ones.

Solidarity is, unfortunately, not a straight and narrow path. The oppressed do not automatically identify with each other, and building bridges between them (like the subtly placed bridge which appears on each of the trips LGSM take to Onllywyn) takes a great deal of patient work, and the bridges are necessarily fragile creations in the capitalist world which melts everything solid into air. It is to Pride’s enduring credit that it deals with the good, the bad, and the ugly of creating and maintaining solidarity.

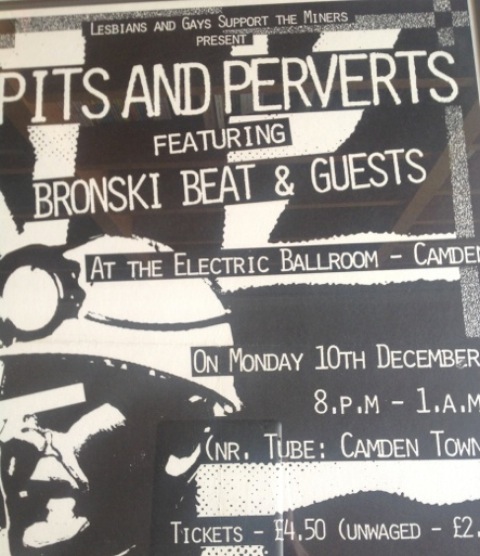

The turning point of the film comes when Margaret (Liz White), the president of the union support committee, makes a fateful decision to inform the press about LGSM’s activity in Onllwyn, despite the earnest attempts by Dai, Hefina and others to get her to see the benefits of such solidarity. The newspapers descend on Onllwyn, right-wing tabloids spreading lurid tales of “perverts supporting the pits.” Despite the creativity of Mark and the other LGSM activists who stage a wildly successful “Pits and Perverts” benefit concert, this sets the stage for a union meeting, moved up to prevent LGSM attending, where the miners, fearful of their struggle being undermined, vote to not accept any further aid from the gay activists.

It would be easy for us to write off the actions of Margaret as merely closed-minded in an atmosphere that otherwise speaks a brilliant tale of solidarity between two struggles. The fact that she has much support in the community for her actions, and the struggles her opponents have to constantly wage for the acceptance of LGSM speaks otherwise. Margaret is indeed closed-minded, but she represents the closed-mindedness ingrained in attitudes that can emerge in defensive labor struggles, as the miner’s strike unfortunately ended up being.

As against the pleas of activists like Mark who call on both the gay activists and the miners to have a good offense as the best defense, it can sometimes seem reasonable in the atmosphere of deep adversity the miners were faced with to focus only on their struggle, and look suspiciously at activists such as LGSM as promoting a “different agenda.” Such is the attitude that leads a labor movement to defeat, but it is a part of the movement and a real part of the history nonetheless.

The interpenetration of the gay struggle and the miners’ strike in Onllwyn briefly offered a concrete realization of the promise of labour solidarity. As Dai describes, in the form of a handshake, this is “the most basic thing about solidarity — you support my rights and I support yours.” The involvement of LGSM in the strike, and the subsequent support of many miners for gay rights contained the potential in it for a real social movement to challenge both pit closures and sexual oppression. The miners’ struggle could have pointed a way toward the future rather than simply defending existing conditions. This, unfortunately, was potential that would go unrealized.

* * *

There are, as with any film, a number of things we might point out about the problems of a film like Pride, both in its story and its format. I’ll try to deal with a number of these points before wrapping up.

First of all, the movie is not exactly true to life when it comes to the divisions that haunted LGSM throughout its short existence. Though the split of several women activists away from the group to form Lesbians Against Pit Closures is briefly touched on, there is little effort made to understand the struggles of lesbians within a male-dominated group like LGSM to be taken seriously and have space for themselves as women activists. When this does come up, it is dismissed outright by Mark’s character.

Miners battling with cops

As I suggested above, there were also some deeper rifts within the group that came out of the very real political differences between members of the Communist Party and a number of other LGSM members who were in different Trotskyist formations. For example, when the Thatcher government began importation of scab coal from Stalinist Poland, Mark Ashton, a member of the CP, staked his reputation as leader on it and threatened to resign if LGSM condemned the government of Marshal Jaruzelski for its actions.

This speaks to a difference of approach between the CP, which was intent on building a “rainbow coalition” of oppressed groups like gays alongside the working class, as opposed to that of some Trotskyists who saw gay issues as primarily working-class issues. That the film tends to evade these differences in the movement tends to present LGSM as a less contradictory formation that it ended up being.

There are also debates to be had on the form the story takes, which have unfolded in various corners of the British left on Facebook. One objection is that the dance numbers, the upbeat tenor, and the stories of personal liberation like that of Joe from Bromley (George McKay) reduce the story of LGSM to a style that might be seen in just about any British film these days. One suspects that there is a breed of leftist that can’t handle anything politically good that is also popular, but I’ll leave that to the side.

In my opinion, this objection ignores the ability of filmmakers like the makers of Pride to take up and subvert traditional storytelling and morals of popular culture. Most of the stories that come out of the Great Miners’ Strike, indeed, are tales of personal liberation counterposed against collective defeat — Billy Elliot is particularly instructive here — and which have the effect, politically, of promoting an agenda of individual liberation while undermining any idea of collective resistance, in a way that that is quite conducive to neoliberal ideology.

For me, Pride’s great achievement was to flip the script. Nowhere is this more clear than in the case of Joe, who arrives at the beginning of the movie at a gay pride march and is our way into the activist culture that gives birth to LGSM (it is key to note here that Joe, unlike most of the other activists portrayed, is a fictional character). The experience of LGSM, forming intense personal bonds of friendship and solidarity with his fellow activists and the miners of Onllwyn give him the courage to come out of the closet and depart the backward, homophobic household of his parents. Here, personal liberation is not the alternative to collective struggle, but one effect of its condition.

* * *

The defeat for the gay activists and the miners was felt on a personal as well as a political level. For Joe, the salacious headlines reveal his homosexuality to his parents, who immediately demand he renounce his lifestyle (out of love, of course). Reggie (Chris Overton), continuing to collect for the miners amidst shouting that “gay men are dying everyday, that’s what you should be collecting for!” suffers a vicious beating and ends up in the hospital. Jonathan, whose skepticism about the miners’ cause was overcome, is faced with an HIV diagnosis, as is Mark Ashton (this is also true to life — he died from AIDS in 1986.)

Similarly, for the miners, it is the effective end of their way of life. “The pits are the people,” as the elderly, and closeted gay, miner Cliff (Bill Nighy) says to Mark, and their closure put communities such as Onllwyn on borrowed time. In these villages all that remains is crime, drugs and alcoholism. The only real victory for both groups is they can hold their heads high. Despite epic demoralization in the latter days of the strike, Onllwyn’s miners resist scabbing to the last and march back to their pit united, accompanied by Joe and Mark, who come to witness the final act.

Flyer from "Pits and Perverts" benefit show

And yet, there is something about the encounter of a group of young gay militants and an isolated Welsh mining community in 1984-5 that can reach out in the form of Prideto inspire us in very different, less interesting and more confusing times. This is beyond the fact, as pointed out in the credits, that LGSM’s activity served to motivate the NUM, the British union movement and the Labour Party to support equal rights for the gay community.

Part of this is that their encounter has a concrete legacy in British politics. LGSM activists, those who did not fall victim to HIV, are still around and can still testify to their achievement. Siân James, the miner’s wife who Jonathan urges near the end of the film to go to college, got a degree in Welsh language after raising her children and went on to become a left-wing Labour MP. Dai, after the closure of his pit, got a Masters degree at Oxford and today works for the broadcasting union BECTU. The experience of gay solidarity with the miners is still alive.

But there is also something else. In his justly famous last essay “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Walter Benjamin writes, “only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And that enemy has not ceased to be victorious.”

As Neil Davidson has pointed out, this poetic passage Benjamin seems to mean something similar to the Party slogan in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four: “Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.” This signifies, conversely, Benjamin’s main contribution to the theory of proletarian revolution: the “spark of hope” we seek to fan can come from the most unlikely of sources, and we have no idea which parts of our tradition may be relevant to our current struggles.

London’s gay pride march in 1985, headed by a hundreds-strong contingent of Welsh miners, ends Pride to the electric guitar and soft British accent of Billy Bragg: “The Union forever, defending our rights/Down with the blacklegs, workers unite/With our brothers and our sisters from many far off lands/There is power in a Union.”

Pride has brought the experience of solidarity between miners and gay activists back to life. Maybe one day we will see a left, a gay movement and a working class capable of remembering and taking advantage of it.

Bill Crane is an American socialist living in London. His writing has been published online at Socialist Worker, ZNet, and elsewhere. He blogs for Red Wedge on books, television and other cultural matters at As I Please.