The Time is Now: Reflections on the Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, Jewish Museum New York, March 17th – August 6th

* * *

IV.

“Secure at first food and clothing, and the kingdom of God will come to you of itself.” – Hegel, 1807

“The class struggle, which always remains in view for a historian schooled in Marx, is a struggle for the rough and material things, without which there is nothing fine and spiritual. Nevertheless these latter are present in the class struggle as something other than mere booty, which falls to the victor. They are present as confidence, as courage, as humor, as cunning, as steadfastness in this struggle, and they reach far back into the mists of time. They will, ever and anon, call every victory that has ever been won by the rulers into question. Just as flowers turn their heads towards the sun, so too does that which has been turn, by virtue of a secret kind of heliotropism, towards the sun which is dawning in the sky of history. To this most inconspicuous of all transformations the historical materialist must pay heed.” – Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Concept of History (1940)

In early 1940, just before he attempted to escape to Spain from Vichy France, the Marxist theorist and art critic Walter Benjamin penned his Theses on the Concept of History. In twenty numbered paragraphs, Benjamin sketches his vision of the task of the materialist historian. In contrast to the historicist, whose method consists of merely adding “a mass of facts, in order to fill up a homogeneous and empty time,” the materialist historian employs a “constructive” method (XVII), piecing together the “tradition of the oppressed” (VIII) from the rubble of the catastrophic past into a “constellation” (XVII) that most accurately reflects the fragmented character of modern reality. While the historicist empathizes with the victors of history, for Benjamin, the task of the materialist historian was to interpret the traces of “what has been” as evidence of what is to be done, namely to break with the ”triumphal procession” in which “[t]hose who currently rule are the heirs of all those who have ever been victorious” (VII). The demand is always the same, for despite the historical specificity of every epoch, which no materialist can disavow, that specificity is purchased time and again at the same price: the oppression of the many by the few. Benjamin saw the interpretation of artifacts as just as much a political task as their creation: the labor of the artist and critic converge in the historical horizon that is the eternal emergency of the present.

The Theses would be the last major work Benjamin completed. On the run from the Nazis as a Marxist and a Jew, he committed suicide in the seaside town of Port Bou, leaving behind a body of work that he surely hoped would itself contribute to the task of materialist history as he understood it. Yet the ambivalence at the heart of Benjamin’s thought has given rise to divergent interpretations. It is arguably the bourgeois Benjamin that has found the most extensive reception in the world of art criticism: the Benjamin of the flâneur, the allegory, the aura of the artwork. As illuminating, and in themselves potentially explosive, as these aspects of Benjamin’s oeuvre are, seen without the lens of his messianic materialism they are the tools of a merely historicist approach to art and culture.

It was all the more intriguing, therefore, to consider which Benjamin would emerge from the exhibition The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, when I went to see it at the Jewish Museum in New York earlier this year. The exhibition is based on the Passagenwerk, or Arcades Project (Cambridge, MA/London: Belknap, 1999), which Benjamin had been working on since 1927, and was left incomplete at his death. An investigation into the ambivalent condition of modernity through the lens of Paris’ new glass and iron shopping arcades, the incomplete Arcades has become one of the most influential texts in modern cultural criticism, and has played no small part in propagating the image of a safe, bourgeois Benjamin fascinated with Baudelaire, fashion, and defunct technologies. I put on my best materialist historian’s spectacles when I went to the show, keen to see what kinds of destructive Benjaminian readings the artworks on display might yield.

The materialist historian's spectacles.

The exhibition is curated according to the principle of constellation that defined both Benjamin’s own method, and that of the Arcades edition. The Arcades text has been reconstructed thematically, with fragments of Benjamin’s own writing sitting alongside excerpts he collected in “Convolutes” [Konvolute] listed from A to Z under relevant headings. In the exhibition, artworks represent individual Convolutes, and are also paired with textual fragments gathered from a variety of sources. The order is disjointed, rather than running in a neat, linear fashion, which quite effectively mimics the fragmentary structure of the book in three dimensions. There is far too much text on the surfaces for even the most assiduous gallery-goer to digest, though rather than seeing this as a curatorial miscalculation, one might read it generously in a Benjaminian vein and consider that whatever one visitor has overlooked has almost certainly been read, perhaps fleetingly, perhaps with care, by another. There are too many works here to comment meaningfully on them all. The ones I chose to review were those that spoke most audibly to the Benjamin I know.

A [Arcades, Magasins de Nouveautés, Sales Clerks]

In Convolute A of the Arcades, Benjamin cites a description of the newly opened shopping arcades from the 1852 Illustrated Guide to Paris. The passage paints a picture of the arcades as a welcoming “refuge” of “glass-roofed, marble-panelled corridors,” in which passers-by could find protection from the elements during “sudden rainshowers.” Yet these harbours of light, warmth and “industrial luxury” were more than merely covered promenades. “Lining both sides of these corridors,” the Guide continues, “are the most elegant shops,” whose owners “have joined together for such enterprises,” so that the respite they offered to the “unprepared” outside was “one from which the merchants also benefit” (Arcades, p. 3).

The Paris arcades were the first shopping malls, the quaint ancestors of the American megaliths depicted in Walead Beshty’s American Passages (2010-2011), an automatic slide show projecting images of empty shopping centers onto a blank wall. The arcade, and the mall after it, was integral to the capitalist dream of consumer comfort. However, if in the nineteenth century arcades could still be seen as proof that “industry is the rival of the arts” (ibid.), the images of twentieth-century American malls in Beshty’s work demonstrate the extent to which all pretension to beauty has been erased from these commercial spaces. Once the hallmark of the American Dream, many of these buildings have been abandoned as capital has moved elsewhere, and now they stand vacant, littering the landscape like the deserted carapaces of an army of giant, upwardly mobile crabs. The desires once projected onto their interiors have been diverted, unfulfilled of course, to the new virtual corridors of gleaming light that beam back to us from our computers in this era of screen capitalism.

Walead Beshty, American Passages (2011)

i. [Reproduction Technology, Lithography]

In his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility” (Selected Writings, Volume 3, 1935-1938, Cambridge, MA/London: Belknap, 2002, 101-140) Benjamin speculated about the ambivalent effect of modern technology on the production and experience of art. Although in principle a work of art could always be reproduced or imitated, before the invention of photography, film, and modern print techniques, originals had a certain aura connected to the fact of their temporal and spatial locatedness. The Venus de Milo could only be viewed if you were standing right in front of it in the Louvre, for example. With the advent of reproduction technologies, however, great works could be copied and viewed repeatedly, whenever and wherever one wants. For Benjamin, these technologies had an emancipatory aspect, making the experience of art available to a much larger audience, even if something of the “mystery” of art was lost through its reproducibility. However, he also saw a dark side to techniques of artistic simulation. The rise of fascism, as the “aestheticization of politics,” had seen art put into the service of a murderous ideology, by erasing the boundary between image and reality. Benjamin called for the “politicization of art” in opposition: the investment of productive forces in the critical act of creation.

In Timm Ulrichs’ Walter Benjamin: “Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit” – Interpretation: Timm Ulrichs. Die Photokopie der Photokopie der Photokopie der Photokopie (1967), the cover of the published version of Benjamin’s essay is reproduced in multiple photocopies, obscuring the image as the contrast fades increasingly to white. The montage of 100 copies, each based on the same image and yet minimally unique, recalls Andy Warhol’s series of screen printed Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Yet whereas Warhol’s piece set the dialectics of individual and copy at work in a single temporal frame, Ulrichs’ highlights transience and fragility as the image fades filmically from top-left to bottom-right. The work stages the question of whether endless reproduction ultimately depletes meaning over time. For Benjamin, “one of the tasks of art has always been the creation of a demand which could be satisfied only later.” The demand that emerges from Benjamin’s artwork essay is none other than the productive use of technology in order to do away with private property. The only alternative he saw was the increasing escalation of war, since it is the only activity that can “set a goal for mass movements on the largest scale while respecting the traditional property system.” The mass movements of the twentieth century have all but disappeared, but the conflict between productive forces and the mechanisms constraining them has not. Ulrich’s work invites the viewer to imagine the consequences should Benjamin’s insight disappear from memory like the image from a reproduced photocopy.

Timm Ulrichs, Walter Benjamin: “Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit” – Interpretation: Timm Ulrichs. Die Photokopie der Photokopie der Photokopie der Photokopie (1967)

U [Saint-Simon, Railroads]

“The problem,” as Jacques Lacan acknowledges in a quotation accompanying Martín Ramírez’s Untitled (Trains and Tunnels), A, B (1960–63) “is knowing whether the master-slave dialectic will find its resolution in the service of the machine.” Machines are the dead products of living labor, and ought to serve that labor, the better that it may live. To put living labor in the service of the machine would, on the contrary, be to surrender entirely to the death drive.

Railroads embody the dual promise and threat Benjamin saw in technology. The construction of railroads made the world smaller, distances and the time it takes to travel between them contracted. In the Arcades, Benjamin quotes Benjamin Gastineau, who, in La Vie en chemin de fer (1861), argued that the advent of railroads changed humanity’s relationship to nature, even nature itself. “Before the creation of the railroads,” Gastineau argues, “nature did not yet pulsate: it was a Sleeping Beauty. […] The heavens themselves appeared immutable. The railroad animated everything. […] The sky has become an active infinity, and nature a dynamic beauty” (Arcades, p. 588).

They also profoundly changed relations between labor and capital. Writing in Die Neue Zeit in 1904, Paul Lafargue argued that the construction of railroads brought about a shift in the mode of property by requiring industrialists to hand over control of capital in order to form the large consortia needed for the mammoth task at hand. Meanwhile, M. de Molinari, editor in chief of Le journal des economistes, is claimed to have been the first to put forward the idea of a labor exchange, seeing in railroads the means necessary to transport otherwise immobile unemployed labor.

Born in rural Mexico, from 1925-1930 Martín Ramírez was a railway worker in California, where he moved to find employment, leaving behind his wife and three children. Isolated, exploited, and unable to speak English, after six years Ramirez ended up unemployed and homeless, and developed severe mental health problems. In a series of institutions, he began to create drawings in which trains, tracks, and tunnels merge in masses of lines that recall at once rolling hills, vaulted structures, and the patterns of Mexican folk art. Benjamin wrote of Ramírez’s work that it confronted the viewer with a “fascinating linguistic wilderness,” depicting desires that perhaps yet have no name.

Martín Ramírez, Untitled (Trains and Tunnels), A, B (1960–63)

k [The Commune]

Walter Crane was an English artist and book illustrator whose Arts and Crafts style helped to revolutionize children’s picture and toy or movable books. Under the influence of William Morris, Crane became closely associated with the international socialist movement, and was committed to bringing beauty into the lives of working people. Although not an anarchist himself, Crane contributed to a number of anarchist publishers including Liberty Press, and Freedom Press, and supported the four Chicago anarchists executed in connection with the bombing of Haymarket Square after a labor demonstration in 1887. Many of the illustrations he produced in support of the international socialist movement became iconic, among them The Triumph of Labour, a small engraving designed to commemorate International Labor Day 1891 and dedicated to the wage-workers of all countries.

Crane’s image is reproduced on a monumental scale by Andrea Bowers, whose Triumph of Labor (2016) is a gallery-wall-filling work of marker on cardboard. It is an orgiastic image: workers embrace one another and hold banners saying “Dignity and a Living Wage,” and “The Land for the People.” By reproducing Crane’s engraving, Bowers both draws on and reinvents the memory of the tradition of the oppressed. In Convolute k of the Arcades, Benjamin cites a placard of the Paris Commune dated April 15, 1871: “Within the Commune emerged the project of a Monument to the Accursed, which was supposed to be raised in the corner of a public square whose center would be occupied by a war memorial. All the official personalities of the Second Empire (according to the draft of the project) were to be listed on it. Even Haussmann's name is there” (Arcades, p. 790). In the text accompanying the artwork, there is a fragment from Marshall Berman’s All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity (2012), in which Berman criticises Robert Moses, the controversial New York city planner, often compared to Baron Haussmann because of the damage his designs wrought on the social geography of the city. Moses’ interventions, Berman writes, transformed “evolution into devolution, entropy into catastrophe,” and created “the ruin on which this work of art”—New York City—“is built”. The procession of workers in The Triumph of Labor runs historically counter to the one Benjamin describes in his Theses. It is a jubilee that turns catastrophe into freedom.

Andrea Bowers, Triumph of Labor (2016)

X [Marx]

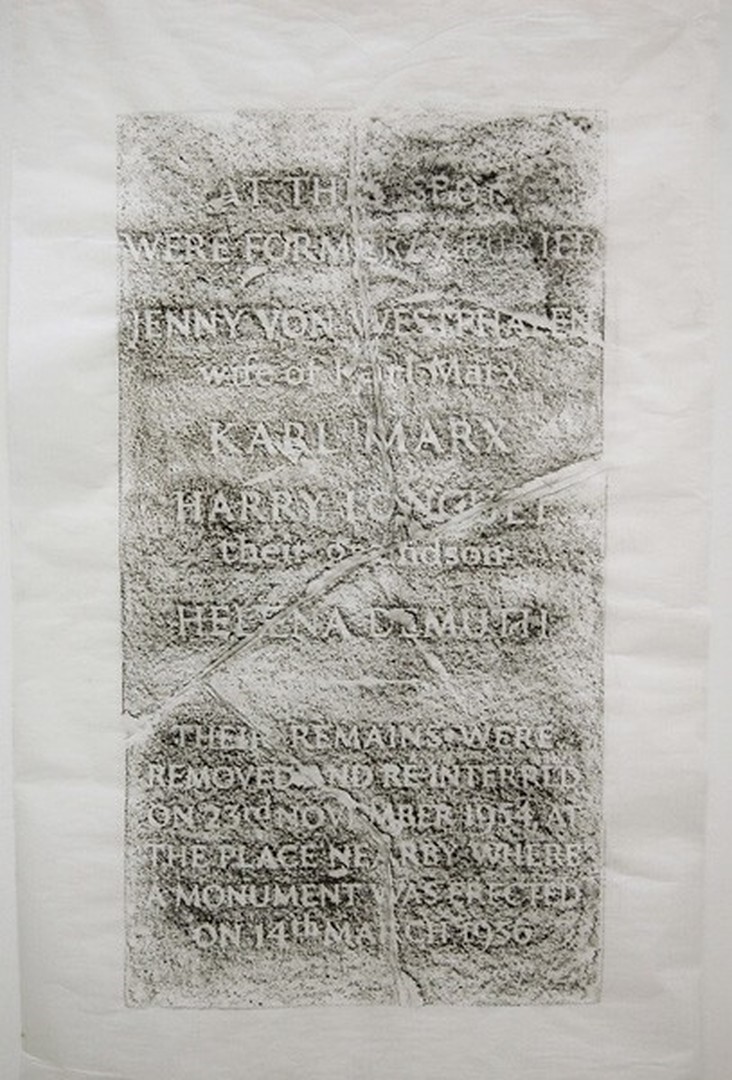

As the result of a petition made by the British Communist Party, Karl Marx’s remains were moved in 1954 from their original burial site (1883) to the main avenue of Highgate Cemetery in London. In 1956, a 4-meter high bust of Marx was unveiled. The original gravestone can still be identified among the weeds, with a broken marker serving as a disclaimer, announcing to the visitor that Marx is no longer buried there. Milena Bonilla’s installation Stone Deaf (2009-2010) is composed of a rubbing of the original gravestone and a video showing ants, wasps and a snail crawling along its cracks.

Bonilla’s piece draws our attention to the discrepancy between Marx the man and Marx the legend. “The action of a man,” as the quote from Hugo Fischer’s Karl Marx und sein Verhältnis zu Staat und Wirtschaft (1921) included under Convolute X reads, “is already more than the agent of this action. […] The action already takes place in a higher sphere, which has the future for itself.” Insects crawl on Marx’s original gravestone, living their lives in the eternally recurrent economy of coming to be and passing away. Meanwhile Marx lives on, elsewhere, everywhere, in and through the lives of those who have read his works. Of his own generation, Benjamin wrote, they had learned that “capitalism will not die a natural death.” A spectre haunts it still.

Milena Bonilla, Stone Deaf (2009).

R [Mirrors]

“Let two mirrors reflect each other; then Satan plays his favourite trick and opens here in his way (as his partner does in lovers' gazes) the perspective on infinity. Be it now divine, now satanic: Paris has a passion for mirror-like perspectives” [R1,6]. “Since when the custom of inserting mirrors, instead of canvases, into the expansive carved frames of old paintings?” [R1,5].

From a Benjaminian perspective, the cult of celebrity might be seen as just the modern expression of the age-old need to worship gods, to see them in ourselves, to see in them what we would want to be. The celebrity magazine cover is the contemporary portrait of some saint, or member of the aristocracy, only now it is available to all, at any time, in print or digital format.

“The sense of the ‘abyssal'” in Baudelaire, Benjamin writes, is “to be defined as 'meaning.' Such a sense is always allegorical.” Modernity is Janus-faced, just like the mise en abyme effect created by Mungo Thomson’s June 25, 2001 (How the Universe Will End) March 6, 1995 (When Did the Universe Begin?) (2012), two mirrors positioned on opposite walls with the logo from TIME Magazine emblazoned across the top of each. Stand in between them, and what do you see? Only yourself, reflected for all eternity as everyone who ever lived and died to create your present, and everyone who will ever live and die to create more of the same unless you, standing between these two horizons, do something to break the cycle. The time is now.

This review appears in our third issue, “Return of the Crowd.” Purchase a copy at wedge shop.

Red Wedge relies on your support. If you like what you read above, consider becoming a subscriber, or donating a monthly sum through Patreon.

Cat Moir is an academic and writer living in Sydney, Australia. In life as in work she is committed to socialism, feminism, and the pursuit of utopia.