The student butterfly that flapped its wings in Paris, May 1968 led to an earthquake which shook factory walls across western Europe in the 1970’s. Out of the dust emerged an ugly snarling rodent called punk rock.

The 1970s in the UK was a time of open conflict. Strike leaders sent to prison and then freed by a massive strike wave, teenagers fighting in the streets against each other, against the police and against the army in Ireland, miners strikes, power cuts, three day week, women battling for equal rights, Tory government brought down. The working class – loud, proud and winning.

Then it all began to turn sour. The Labour government delivered bitter betrayal with the aid of the union leaders. There was a sharp rise in unemployment – especially among the youth. Racism rose and the fascist National Front started to grow, parading in the streets and doing well in local elections.

The great expectations of the 1960’s had faltered and failed. And the punks declared “There’s no future in England’s dreaming.”

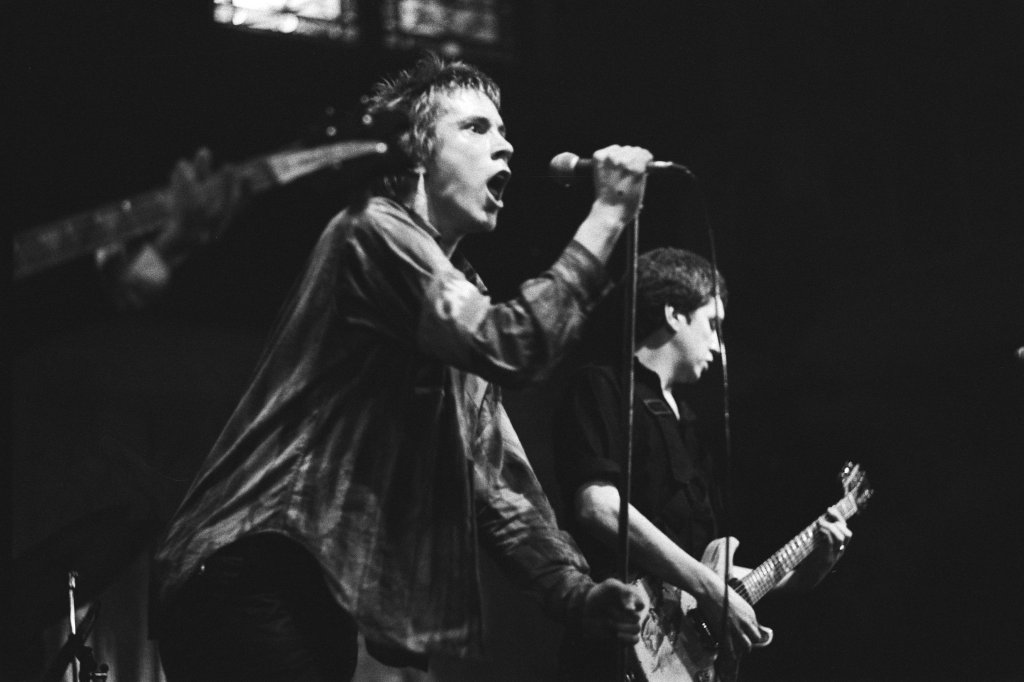

Who were these punks? A bunch of angry, frustrated teenagers? Many of us were that (and more besides) but a closer look at the key players of punk reveals a collection of dedicated mischief makers, immigrants, ethnic minorities and political radicals – society’s outsiders and oppositionists. The top two contenders for the punk rock anti-crown were the Sex Pistols and The Clash – noisy harbingers of the raging hordes to follow.

No Future

The Sex Pistols had long been a twinkle in the eye of their future manager Malcolm McLaren, a self-proclaimed ‘social rebel’. McLaren identified with the Situationist International (SI) and in particular the UK wing King Mob, which “promoted absurdist and provocative actions as a way of enacting social change”.

In May 1968 McLaren tried to travel to Paris to join the demonstrations there. However he was unsuccessful and instead, with fellow student Jamie Reid (Pistols’ future designer), McLaren took part in an occupation of Croydon Art School. In 1969, while at Goldsmiths’ College, McLaren organised a free festival/teach-in which featured radical psychiatrist R. D. Laing, dockers leader Jack Dash, SI figures and none of the famous bands he had claimed would be there (“Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd etc”).

From then on he continued his search for a flame of revolt.

Despite the extended strike wave of the early seventies, there was been precious little radical response in the British music scene. Even the best selling song that referenced the strength of the working class, ‘Part of the Union’, was intended as a satire – if not received as such by the confident class warriors of the time. “You won’t get me I’m part of the union…” they sang along.

McLaren attempted to utilise his Situationist-inspired ideas to link shock tactics, pop culture and entrepreneurial skills – including rebranding the New York Dolls band, the uncles of punk, in red patent leather and having them perform in front of a huge hammer and sickle backdrop.

Eventually he hooked up with a couple of lumpen proles with nothing to lose but their stolen guitars and was introduced to an ultra-alienated child of Irish immigrants. Still a teenager, John Lydon was a poetry writing further education student who was solidly anti-racist and saw through England’s dreaming of empire with a beady eye. Lydon became Johnny Rotten and his poetry became lyrics torn from the news of the day…

Is this the MPLA?

Or is this the UDA?

Or is this the IRA?

I thought it was the UK

Or just another country

Another council tenancy

I first spotted the Sex Pistols at the end of August 1976. They erupted from the television set, snarling, “I am an anti-Christ, I am an anarchist… Anarchy… in the UK”. But dancing on stage with them was a woman dressed as a storm-trooper and wearing a Nazi armband. Who were these punks? Rock’n’roll rebels? Anarchists? Nazis?!

The Pistols’ impact was minimal until they landed drunkenly on mainstream media’s heartless heart of tea time TV, swearing in millions of living rooms. “What a fucking rotter…” Again one of the group was wearing a swastika armband.

McLaren continued to engineer Situationist shock tactics like the band’s Jubilee boat trip past the Houses of Parliament and signing their record deal while flicking V-signs in front of Buckingham Palace. The tactics could seem superficial but they helped to spread the word and inspire many teenagers to rally to the cause. But what cause?

Conservative member of the GLC (London Assembly) Bernard Partridge was no fan. “My personal view on Punk Rock is that it’s disgusting, degrading, ghastly, sleazy, prurient, voyeuristic and nauseating. I think most of these groups would be vastly improved by sudden death.”

The Pistols real moment of social significance came in the summer of 1977, when the whole country was supposed to be celebrating the joys of royal rule, the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. To the fury of patriots, the Pistols expressed what many were thinking but few were saying so publicly or as imaginatively:

God save the queen

The fascist regime

They made you a moron

A potential H bomb

God save the queen

She ain’t no human being

And there is no future

In England’s dreaming

The song raced to the top of the pop charts, embraced by punky hordes some wearing Stuff the Jubilee and Rock Against Racism badges. In a few places where the Left were in tune with what was happening, Stuff the Jubilee parties were organised.

At the time of the Jubilee London’s Evening News ran a headline ‘Rock’s Swastika Revolution’. McLaren replied, “The Sex Pistols are not into any political party, least of all the loathsome National Front. Anarchy is not fascism but self rule.” And Johnny Rotten’s mum waded in, “A friend of ours thinks the Pistols are doing more for the country than [Labour Prime Minister] Jim Callaghan”.

What had happened between their first TV exposure and the anti-Jubilee triumph? For that we have to go back again to 1968.

A Riot of Our Own

Joe Strummer was the disenchanted son of a British diplomat, born in Turkey. His big brother had become a fascist and joined the National Front before committing suicide at the age of 19. Joe said, “In 1968 I took my O levels and the whole world was exploding. There was Paris, Vietnam, Grosvenor Square, the counter-culture. It was like riding a rocket but I didn’t realise how lucky I was until later.”

During the early 1970s Joe spent time as a busker calling himself Woody in honour of his hero, and arguably the USA’s most popular communist, the singer Woody Guthrie. The Communist Party (CP) tried to recruit Strummer. “Their main method was through dope” said a friend with him at the time. “We went to their meetings, smoked a lot of their dope but didn’t join.” Joe himself later said, “Toeing any line is obviously a dodgy situation or I’d have joined the CP years ago. I’ve done my time selling the Morning Star at pitheads in Wales and it’s just not happening.”

Joe then joined the musical wing of the squatting and alternative community of seventies London and later said that like many radicals of his generation it was “May 68, the student and strike movement and the 1973 coup in Chile” had been the experiences that formed his political outlook.

Early in 1976 Joe and the other future members of The Clash saw the Pistols singing ‘No Future’ and realised they’d seen the future. The Clash started as a raw rock’n’roll band, but they had the totally transformative experience of being at the Notting Hill Carnival that year. Sick of systematic harassment and ‘heavy manners’ from the police young blacks rose up at the carnival and fought street by street with the police. Joe and Clash bassist Paul Simonon were there.

Black man got a lot of problems

but they don’t mind throwing a brick

White people go to school

where they teach you how to be thick

Scenes of police cowering while bricks and bottles rained down on them and images of police cars being attacked by young blacks had never happened before.

It looked like the street fighting between Irish youth and the British army which was regularly on the TV but was in London. One thing the Establishment feared was a linking of white youth with the black uprising.

White riot I wanna riot,

White riot a riot of my own

All the power’s in the hands

Of the people rich enough to buy it

While we walk the street

Too chicken to even try it

Simonon had grown up in Brixton, his dad was a migrant, artist and member of the Communist Party. Paul was at school with the children of the Windrush generation of Caribbean immigrants whilst Joe had been at Public boarding school in Surrey.

Are you taking over

or are you taking orders?

Are you going backwards

or are you going forwards?

White riot I wanna riot

White riot a riot of my own…

In their first interview, November 1976, Joe asserted, “We’re anti-fascist, we’re anti-violence, we’re anti-racist and we’re pro-creative. We’re against ignorance.”

The Clash soon adopted the hit song from the carnival, Police and Thieves (“All the peacemaker, turn war officer…”) and musically made it their own. The Clash embracing reggae and its militant culture was massively significant – bringing together the two rebel musics of the moment. Bob Marley and the Wailers had made a huge popular breakthrough the same year and now The Clash introduced a younger generation of whites to reggae. Marley paid his own tribute to punk:

Rejected by society (do re mi fa)

Treated with impunity (so la te do)

Protected by their dignity (do re mi fa)

I search reality (so la te do)

It’s a punky reggae party

And it’s tonight

It’s a punky reggae party

And it’s alright

Mick Jones, who was brought up by his Russian Jewish grandma, joined Joe and Paul to create the Clash. They were brought together by Bernie Rhodes who, like his long term friend Malcolm MacLaren, was a product of 1968 and the subsequent period of unrest.

As their manager and mentor Rhodes played an important part in making the Clash such a radical band – urging them to write about their lives of unemployment, boredom and repression. He also sat them down with a pile of radical magazines from the early seventies for inspiration.

Rhodes challenged McLaren for the stupidity of using the swastika as a symbol of shock and provocation. At the first Punk Rock Festival, September 1976 in the basement 100 Club, Siouxsie Sioux of the support band wore a swastika armband and planned to perform a mix of the Lord’s Prayer and Deutschland Uber Alles. Aware of this, Bernie Rhodes, the Clash’s manager refused to let them use the Clash drum kit and pink-painted speakers that night. Future Sex Pistol Sid Vicious, in a swastika T-shirt, called Rhodes, “a fucking old Jew!”

The battle of the armbands continued… Soon Johnny Rotten was wearing a McLaren designed armband which read “CHAOS,” Mick Jones made himself one saying “RED GUARD,” which can be seen on the first album cover. Even if the young punks could claim they were flirting with the symbol of fascism as a way of outraging their parents’ generation. The National Front were threatening to become the third party of British politics and if they were more in tune with youth culture could have made a significant intervention here.

This is where the revolutionary left came in.

Back in August 1976 Rock Against Racism (RAR) had been launched with a letter to the music press. I have written about the impact of RAR elsewhere. Red Saunders, the writer of the RAR letter, was quick in spotting the significance of punk, and The Clash in particular, to the then-fledgling RAR – it was his photos of the band which illustrated the band’s first live review in the NME. The voices of anti-racism and anti-fascism which RAR raised, drew together and amplified were crucial in undermining the use of the swastika as a symbol of punk. Not everyone learnt however, as any glance at images of Malcolm McLaren-managed Sid Vicious will show. Punk and even Two Tone continued to be disputed territory where racists and anti-racists, and to a less extent Nazis and anti-Nazis continued to fight on the battleground that gigs, streets and playgrounds grew to be in following years.

Punk was in many ways a reaction against rock which had become pompous, self-inflated and distant from its audience. By the mid-1970s rock stars were tax exile millionaires living in gilded palaces. The punk revolution challenged the relationship between performers and crowd. “The record industry never wanted 5,000 groups,” said McLaren looking back in 1985. “One group is more manageable. They don’t like the socialist idea that everyone can do it.”

Punk was a democratic art form. The music was basic, the playing rudimentary but the energy, emotion and, crucially, attitude were inspirational. Legend has it that everyone who was at the first Sex Pistols gig in Manchester (July 1976) went on to form a band. To greater and lesser degree that pattern repeated itself across the country.

Inspired by Punk thousands of kids like me and my friends started our own bands to rant and rave about our lives, the world and everything else that filled us with fury. If we couldn’t play an instrument properly it didn’t matter, if we didn’t want to learn we would pound on typewriters and produce seething, opinionated fanzines. Putting out records and putting on gigs was the next step in this culture of DIY ownership, anti hierarchy and cultural activism. Values that can stay with you for the rest of your life. RAR played an important role, benefited from building positive relationships with punk and fed back into its DIY culture.

How did punk’s politics affect the fans? In my experience the Clash and the Pistols articulated, and made attractive, opinions and politics that the fans held already but weren’t present in any popular collective form. For example the politics of anti racism, anti police, opposition to unemployment. (The revolutionary left were attempting to create activist movements around these issues – often in ‘competition’ with the fascists for a similar young audience.) Anarchism was particularly popular from Anarchy in the UK to bands such as Crass a couple of years later. Socialist politics were best expressed in RAR and the anti unemployment week-long marches of the Right To Work Campaign.

I can’t finish without crediting a political aspect of punk that hopefully someone better qualified will return to. The role of women in the punk rock. Patti Smith was the trailblazer and guiding light for punk with her raw rock, street poetry and her unique dress-down style. Caroline Coon, who wrote the first press feature about the punk movement in August 1976, the first book in 1977 and went on to be manager of The Clash said, “The punk movement was the first time that women played an equal role as partners in a subcultural group. It was a huge step forward.” The young women who had been friends and fans of the Sex Pistols and Clash at the beginning soon leapt on stage. A rush of female or mixed gender bands followed; Penetration, X-ray Spex, Slits, and Raincoats to name a few. The Ford equal pay strike of 1968 via the feminist movement for women’s liberation to the Grunwick’s strike by Asian women in 1976 had all affected women’s place in society and in punk rock in particular.

A version of this article originally appeared at revolutionary socialism in the 21st century.

Colin Revolting was in his first punk band in 1977 while still at school in London. Despite being from a revolutionary socialist family it was punk rock and fighting racism that drew Colin to his own revolutionary politics. A life of agitation, both cultural and political, continues to this day with the theatre company Revolting Peasants. More of Colin‘s tales of political protest can be found at the Guardian and revolutionary socialism in the 21st Century.