“There must be some kind of way outta here

Said the joker to the thief

There's too much confusion

I can't get no relief

Business men, they drink my wine

Plowman dig my earth

None were level on the mind

Nobody up at his word

Hey, hey” – “All Along the Watchtower,” 1968

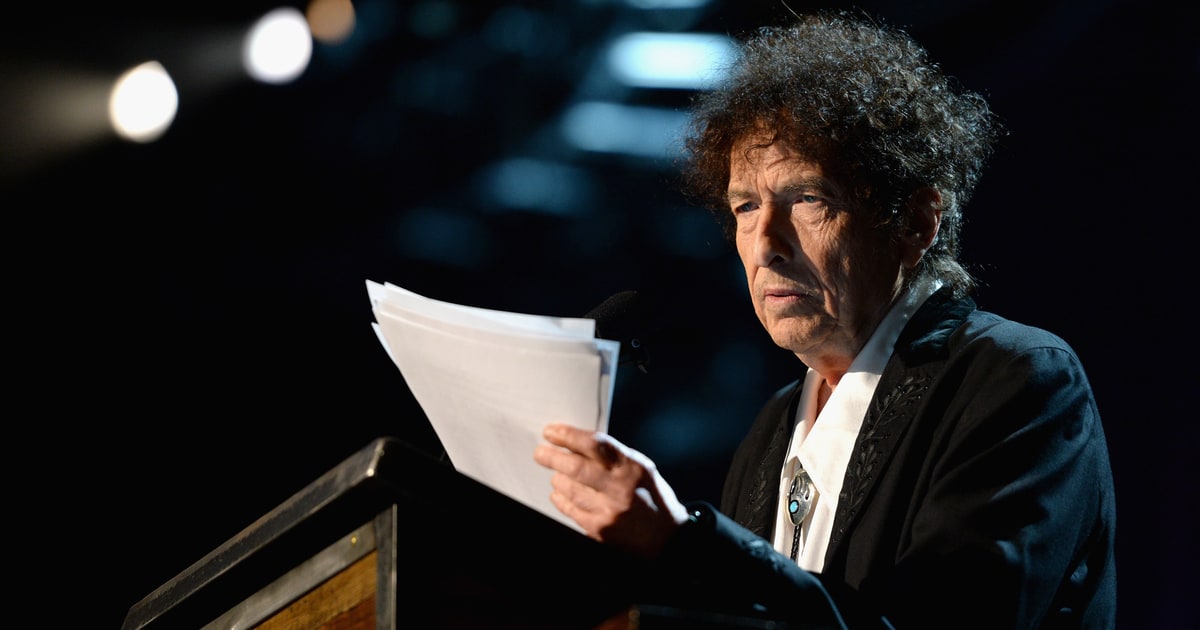

The intelligentsia has been re-traumatized by that dastardly Dylan. First, they had to put up with the very fact that a “rock singer” (or however we label him) is winning a prize that is supposed to be for literature. As Bill Crane put it last fall, “The middlebrow literary establishment in this country, as may have been predicted, has completely failed to understand the significance any of this.”

Crane makes an exquisite formal and substantive argument in defense of Bob Dylan as a poet, though takes a position typical of the Left regarding Dylan’s “turns” after his classic activist period. This largely follows Mike Marqusee’s work, which situates Dylan as sympathetic, but someone who should ultimately be seen as a “renegade” of sorts, compared with, say, Phil Ochs (who loved Dylan and always understood the politics of his “post-political” mid-sixties art). I have some differences with this analysis, as we will see, and one reason is that it fails to allow us to contextualize Dylan’s continued epic punking of the Nobel Prize committee by submitting a speech that contained obvious plagiarism – the kind that those of us who have taught university can find in less than five minutes with Google.

But is it plagiarism when Dylan does it? When an artist wins an award that he doesn’t really want – but could use that sweet money that comes with it – he fulfills his barest responsibilities in the best ways he can. So Dylan, just before the six month cut-off date sent them a speech that is absolutely brilliant in every way imaginable. And like with probably every great work that he has ever produced – from his renaming a Celtic folk song “Girl from the North Country” and then even stealing from himself by using the same music for “Boots of Spanish Leather,” through to his lack of denial that he cribbed from Civil War poets on his 2001 album “Love and Theft” – he stole, he thieved, he did it in a way that he would obviously get caught. And not just from an esoteric source that some such Hardy Boys would find in the darkness of night. No; it was from the Spark Notes. Like a first year student, he dazzled the bourgeoisie with brilliance and baffled them with bullshit.

Folk logic

But Dylan threw in a much more honest self-portrait as a joker/thief that was virtually ignored by those now making age or junkie jokes about Dylan (as if artifice was not part of who he was from the beginning). Dylan’s Nobel lecture contains a section, that to my mind, proverbially, “says it all.”

It follows an opening section in which Dylan puzzles over his work being “literature” and hopes what he is to say is useful. He tells a story about how it all started with him travelling a hundred miles to see Buddy Holly. His reverence for Holly was as much for his look as for his sound; Dylan repeatedly refers to him as an archetype. At this show, where young Robert Zimmerman, like a Deadhead, traveled a great distance, Buddy Holly looked him in the eye! A few days later, Holly’s plane went down, and Dylan, perhaps serendipitously was handed a record by the folksinger Leadbelly. After some ramblings about country blues, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Dylan utters the following,

I hadn't left home yet, but I couldn't wait to. I wanted to learn this music and meet the people who played it. Eventually, I did leave, and I did learn to play those songs. They were different than the radio songs that I'd been listening to all along. They were more vibrant and truthful to life. With radio songs, a performer might get a hit with a roll of the dice or a fall of the cards, but that didn't matter in the folk world. Everything was a hit. All you had to do was be well-versed and be able to play the melody. Some of these songs were easy, some not. I had a natural feeling for the ancient ballads and country blues, but everything else I had to learn from scratch. I was playing for small crowds, sometimes no more than four or five people in a room or on a street corner. You had to have a wide repertoire, and you had to know what to play and when. Some songs were intimate, some you had to shout to be heard.

By listening to all the early folk artists and singing the songs yourself, you pick up the vernacular. You internalize it. You sing it in the ragtime blues, work songs, Georgia sea shanties, Appalachian ballads and cowboy songs. You hear all the finer points, and you learn the details. You know what it's all about. Takin' the pistol out and puttin' it back in your pocket. Whippin' your way through traffic, talkin' in the dark. You know that Stagger Lee was a bad man and that Frankie was a good girl. You know that Washington is a bourgeois town and you've heard the deep-pitched voice of John the Revelator and you saw the Titanic sink in a boggy creek. And you're pals with the wild Irish rover and the wild colonial boy. You heard the muffled drums and the fifes that played lowly. You've seen the lusty Lord Donald stick a knife in his wife, and a lot of your comrades have been wrapped in white linen.

I will admit that when I first read the part about “Lusty Lord Donald”, I hoped that Dylan had made up a mythical figure to signify Donald Trump. “Lord Donald,” as it turns out, was an obscure Scottish lord in the 14th century, as well as a folk song, neither of which involve a lusty man, let alone someone who sticks a knife in his wife. But look at the context in which “Lord Donald” is introduced. He is last in a line of folk figures rooted in genuine folk music and oral working class and subaltern traditions, and whole strange contradictory parts of 19th and early 20th century American life, as chronicled by Ishmael Reed in Mumbo Jumbo.

Workers existed, as did cowboys. Stagger Lee was rooted in a genuine historical figure: a pimp and hustler in St. Louis who shoots a business rival, Billy Lyons, on a riverboat. And of course, Washington is a bourgeois town. As the song goes “Hey everybody listen to me, don’t ever trust that bourgeoisie!” It’s archetypal because its true. Our own Lord Donald knows it! The imagery of revelations suggests that Dylan has a pessimistic and bleak view of the world right now – the crashing of the Titanic. It almost evokes the lyrics of “Desolation Row,” perhaps Dylan’s greatest poem.

The riot squad is restless...

But it goes beyond that. To Dylan, there is no real line between fact and fiction, artifice and article, realism and modernism. The paradigmatic Popular Front folk singer Woody Guthrie started out as a sign painter; what people now call “affective contagions” were deployed in how Guthrie meticulously designed his beat-up fascist-killing guitar.

Music is topical, topics are based on history, history becomes narrative, narrative is told out of order and becomes polysemic. The cycle repeats itself, and it all comes down to the vernacular, the look and the gee-tar.

This is the root of Dylan’s Nobel speech. He’s not at all denying that his work is literature. Dylan’s work, as Crane rightfully argues, deserves its status as literature. It’s to troll the Nobel committee – and his critics – for scholasticism.

It is highly unlikely that Dylan, who always thinks through his public utterances and persona, down to the make-up mustache and eye-liner he sports these days, would just dash this off. This was intentional. Just as was his speech at the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee, referenced in the Marqusee quote in Bill’s piece. Dylan won an award from this committee, a Communist Party front formed after the ACLU purged party members and other Leftists in the McCarthy era. Yet those who attended its banquets, Dylan’s “record buying” audience, the type jested by Ochs in “Love me I’m a Liberal,” were the cast of characters at these events.

Marqusee portrays this speech an early sign of Dylan’s apostasy, but it might be better seen as him taking the piss. Giving the speech in Late 1963, just after the Kennedy assassination, Dylan “went there.”

Denouncing in no uncertain terms the milieu he was addressing as “old,” and counterposing them to those who had gone on a solidarity trip to revolutionary Cuba, Dylan also criticized the mainstream civil rights leadership. His Black friends in the music world didn’t have to wear suits and didn’t have to be “respectable.” Finally, after again referencing the Cuban revolution, Dylan dropped a bomb, while ending with his shout-out to the radical wing of the Civil Rights Movement.

I’ll stand up and to get uncompromisable about it, which I have to be to be honest, I just got to be, as I got to admit that the man who shot President Kennedy, Lee Oswald, I don’t know exactly where —what he thought he was doing, but I got to admit honestly that I too – I saw some of myself in him. I don’t think it would have gone – I don’t think it could go that far. But I got to stand up and say I saw things that he felt, in me – not to go that far and shoot. (Boos and hisses) You can boo but booing’s got nothing to do with it. It’s a – I just a – I’ve got to tell you, man, it’s Bill of Rights, it’s free speech and I just want to admit that I accept this Tom Paine Award in behalf of James Forman of the Students Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and on behalf of the people who went to Cuba. (Boos and Applause).

Dylan was surely, in the vein of Malcolm X’s chickens roosting, being a sly provocateur. Nevertheless, he is driving home the point in a strong way that Oswald was actually willing, in a twisted way, to do something concrete in the face of US involvement in Cuba, the assassination of Lumumba, the beginnings of the Vietnam War. This was his point; not the celebration of individual murder.

He connects this point to those actually doing concrete political work, as opposed to the “old people” in the crowd, that went from thinking they were being poked fun at, to realizing they were the target of his ire. They were, as he later obliquely called them in “It’s Alright Ma,” “social clubs in drag disguise.” Dylan’s political presuppositions – presuppositions that had underlay his art – came crashing down. Merely having a normative critique of American democracy, and being an activist (as Dylan was) in the Civil Rights movement wasn’t enough.

The chimes of freedom

It is in this context that he wrote “My Back Pages”, singing of “using ideas of my maps”, and having “romantic facts of musketeers,” all while enraptured by “crimson flames,” an oblique reference the Communist tradition. It should be noted that Dylan didn’t much care for the Communist Party USA. Contemporaries of his, such as Dave van Ronk were Trotskyists, and he lived for a while with the Trotskyist writer Lenni Brenner. The only Left organization mentioned in his memoir is the “Wobblies,” or Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). It is after a number of elliptical references that follow, that made many take this song (and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”) as a sign of “selling out.”

A self-ordained professor’s tongue

Too serious to fool

Spouted out that liberty

Is just equality in school

“Equality,” I spoke the word

As if a wedding vow

Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now.

This stanza crystallizes the specificity of Dylan’s move away from Popular Front folk music politics, but towards a wider, more radical cultural critique. Simultaneously, however, it is seen by Dylan scholars as a statement of apostasy, as if “equality” was no longer something he believed in. It gives comfort to those, both on the Left and amongst those Liberal Americanists to write Dylan out of radicalism.

It would seem, however, that he is critiquing the “self-ordained professors” of the liberal intelligentsia for having the audacity to think that formal equality would bring substantive emancipation to black people, workers and those others who deserve to hear the “chimes of freedom.” Given his focus, along with the movement in which he was embedded, on achieving substantive political reform going only “half the way with LBJ,” he could no longer utter in a formal juridical discourse, a “wedding vow”; it had to be struck for, fought for. It is no surprise that contemporaneous with this, he wrote a much more poetic vision of change, “Chimes of Freedom,” in which impressionistic lyrics surround pleas in regards to…

Flashing for the warriors whose strength is not to fight

Flashing for the refugees on the unarmed road of flight

An’ for each an’ ev’ry underdog soldier in the night…

Tolling for the rebel, tolling for the rake

Tolling for the luckless, the abandoned an’ forsaked

Tolling for the outcast, burnin’ constantly at stake.

The contrasting vision of “equality in school” as opposed to fighting for total human emancipation is redolent of Karl Marx’s “On the Jewish Question.” In this work Marx criticized Bauer, who like himself was a secular Jew and a Left Hegelian, for claiming that Jews are incapable of being free due to the specificity and generality of their religion. Thus, argues Bauer, Jewish emancipation, as was occurring in more liberal areas of Prussia at the time, was not worthy of radical support. Marx, on the other hand, historicizes the stereotypical “Jew” of Bauer’s imaginary, but more importantly, even if granting these historically specific practical characteristics, there was no contradiction between that and “equality in school”, that is to say, formal equality. The chasm between formal and substantive equality is thus captured in the juxtaposition of being “younger” than the wise professor who reduces liberty to formal equality, with those who fight for all of the oppressed until they hear the crashing of the chimes of freedom. And even so, the degree to which one is emancipated is contextually determined.

Ah, my friends from the prison, they ask unto me

“How good, how good does it feel to be free?”

And I answer them most mysteriously

“Are birds free from the chains of the skyway?”

The theme of what emancipation would look like and what aspects of the old were portents of the new would be the specific theme of the work within Bob Dylan’s next, and arguably, most artistically successful era, from 1965 into 1966. In the fall of 1964, Dylan had started playing a number of new, elliptical and impressionistic songs as part of his live sets, though they had yet to be issued on vinyl record. In early 1965, in the midst of recording this new music, going beyond the hint of his previous album title Another Side of Bob Dylan, Dylan was asked by a journalist why he no longer wrote protest songs.

“All my songs are protest songs” was his reply. Yet Marqusee asks “Was anyone ever as quickly, or as tenderly disillusioned as the young Dylan? And was anyone ever as arrogant?” Dylan was not disillusioned at all – this is a fundamental misread betraying inadequate periodization of his work – and this follows with Crane claiming that Dylan “abandoned folk music and progressive causes” after 1964, even though, as shown, he was still writing deeply committed songs well into his career, with the turn toward reaction more realistically situated after his Christian Fundamentlist/Zionist period in the eighties.

Marqusee writes as if Huey Newton’s reading of Highway 61 Revisited is mere ideology or something like that. The New Left’s encounter with Dylan came entirely from the period in which he allegedly was “arrogant and disillusioned.” To suggest the mournfulness of John Wesley Harding, in particular, is not about Vietnam is absurd. It’s his most didactic record, making Freewheelin’ seem like Sgt. Pepper.

And that is precisely the point. Not only are all his songs protest songs, and they still are. Even when he adopts and consciously has shitty politics, Dylan has something extra that perhaps no one else who did “rock music” had or will have. At the beginning of Dylan’s career, it would be no exaggeration to make the claim that the Left, in both its old and new forms saw Dylan as an inspirational figure at the beginning of his career. Yet a distinction needs to be made between the Left’s hopes for Dylan before his outgrowing a didactic modality of expression, and the Left’s continued wonderment at his mysterious and evocative words, equally historically specific and polysemic.

Dylan himself (as he has implied in his exceptionally esoteric memoir), as well his constituency, wanted at the beginning of his career to pigeonhole him in a category that seemed to have surpassed its relevance. That is to say, a Popular Front troubadour, a proletarian chronicler. Dylan’s single-handed negation of that archetype, out of which came the chameleonic individualist icon that is the artist we now know as Bob Dylan. In doing so, he opened up a wide field of space for musical and poetic experimentation, yet also enhanced, perhaps inadvertently, a focus on the individual. This focus on individual iconography has proved a double-edged sword in music production, analysis and even appreciation.

Perhaps such a focus on Dylan can be challenged to make the case that to imbue Dylan with such historical power and relevance, perhaps more so than any other artist discussed in this project, is to fall prey to an individualist analysis of the conjuncture. But Dylan is to this constellation a figure on the level of Lenin for the Russian Revolution or DaVinci in the Renaissance. He is not a mythologically singular figure, he actually is a historically singular figure. It seems he may well be aware of his significance as he is an elusive figure and a private individual, preferring to embody the role with the cunning that reason has foisted upon him.

So when he had to write that speech, Dylan ‘s gonna Dylan. You gotta serve somebody. He consciously situated himself as being informed primarily by music and the tradition of American folk songs. He exhibited an understanding of their historic specificity and the rhetoric, vernacular and song-style of this antinomian tradition. But this was not sufficient, as Dylan notes he was also informed very deeply as a reader of literature for the Nobel committee, providing him with “a way of looking at life, an understanding of human nature, and a standard to measure things by.”

And then he trolled them.

The problem, then, with this narrative of a “break” in Dylan is akin to the problem with Louis Althusser’s reading of Marx. It suggests discrete periods, and leans towards instrumentalizing both analysis and appreciation of cultural production towards something quite didactic. The argument serves in particular those liberal ideologists like Sean Wilentz and others who make up the “Dylanology” industry. They wish to present an apolitical Dylan, a surrealist individualist libertarian. Like Marxologists with The Grundrisse, these Dylanologists elevate The Basement Tapes and unreleased material in general. They are fetishes for having it all. Something no doubt loved by Sony, which recently issued a box set of his recording sessions of 1965 and 1966, featuring an entire compact disc of every take of “Like a Rolling Stone.” Like the Leftist venerators of the folk-singing Dylan, they also can’t see the forest for the trees.

The crux is, as perhaps only the filmmaker Todd Haynes understood, Dylan was all of these things and none of them. This isn’t to fall into a postmodern trap, like Christopher Ricks, and see Dylan as a web without a spider, as someone having no “there” there. The point is to realize that this whole idea of him being mysterious and contradictory and so on is a ruse, a MacGuffin, fake news. It prevent people from appreciating the historical material itself, as did most revolutionaries in the sixties and beyond.

Red Wedge is going quarterly with our next issue. But we need your help to do it. Read more about it, and donate through Patreon.

Jordy Cummings is a critic, labor activist and PhD candidate at York University in Toronto. He is on the editorial collective of Red Wedge.