“What makes us rise up? It is forces: mental, physical, and social forces. Through these forces we transform immobility into movement, burden into energy, submission into revolt, renunciation into expansive joy.” – Georges Didi-Huberman, curator of Soulèvements.

As Ben Davis wrote following Brexit and the election of Trump the “art world” is dangerously out of touch with political and social developments "down below." The contemporary art world – so thoroughly shaped by neoliberalism and its post-modern cultural ideology – was not prepared for the failure of its underlying supports. Despite the anti-historical pretenses, enshrined in the Museum of Modern Art’s Forever Now painting exhibition last year, a bourgeois ethos of progress had long-infected the art world. But there is no such thing as automatic progress. Channeling Walter Benjamin’s “Angel of History” Brett Schneider writes:

A great wall has been erected by none other than the “politicized” culture of contemporary art. When artists post Boschian visions of hell on instagram to allegorically express their feeling of what the world has become after the election, it really shows that now it can be seen for what it has always been.

Goya, Disasters of War (Spain, 1810-1820)

In the wake of the Kelley Walker debacle at the St. Louis Contemporary Art Museum, also noted by Schneider, the poverty of the official art world should be clear. It is not structurally or ideologically prepared to deal with social realities of “Trump’s America”; or a world in which a neo-fascist political party barely loses the Austrian election, where the far right is gaining ground in France, and Angela Merkel, the purported “liberal bulwark” of Western Europe, proposes bans on Muslim dress. Moreover we must acknowledge that neoliberalism and gentrification are already killing us – and the neo-fascists emboldened by Trump’s victory will be even worse.

Leonard Freed, Residents of Guernica in front of a mural replica of

Pablo Picasso's painting (1977)

We desperately need to explore a new genealogy for radical art – one that does not focus on obsessive materiality or abstracted gestures (isolated from social catastrophe); that does not avoid the brilliant moments of resistance that sustain us, but is not simply propaganda (although we need propaganda). Soulèvements – curated by philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman (winner of the 2015 Adorno Prize) – on display at the Jeu de Paume in Paris –provides an important contribution to exploring an alternative tradition for radical art.

Eduardo Gil, Silhouettes and Cops (Argentina, 1983)

Casasola, Soldaderas ready to fire at the forces of Jose Ines Chavez Garcia (Mexico, 1914)

In a (mostly quite good) review Emily Nathan describes the exhibition as

a thought experiment conducted through images. As its title suggests, the show’s theme is the notion of “rising up,” and Didi-Huberman tackles the many facets of that broad concept through paintings, drawings, films, sculptures, videos, installations, and archival documents, made across centuries and geographies.

André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, The Dead of the Paris Commune (1871)

But Didi-Huberman does even more than this – he has constructed a complex materialist teleology, one that is not deterministic, and one that acknowledges contradiction and counter-vailing tendencies, including the individual subjectivity of artists and social positions.

Soulèvements includes (but is not limited to):

- Documentary imagery of actual revolutions and social struggles – from the Paris Commune to the Cuban Revolution and the Black Panthers, etc.

- Avant-garde agit-prop from Jean Heartfield and others.

- Revolutionary sketches by Gustave Courbet (of French Romantic-turned-Realist and Commune notoriety).

- Books and designs from Dada, the Surrealists and the Situationist International.

- The gothic romanticism and realism of Francisco José de Goya (in particular The Disasters of War).

- Popular forms of resistance art.

- Popular forms of "poking" fun of resistance – such as Honorare Daumier’s Les Femmes Socialistes.

- Other records of struggle and tragedy – such as the graffiti written on jail walls by Nazi prisoners in Athens during World War Two – a social palimpsest of imprisoned resistance.

- Third-campist experimental painting from Sigmar Polke (Against the Two Superpowers: For a Red Switzerland).

- Joseph Beuys’ utopian socialist plans for a world without political parties.

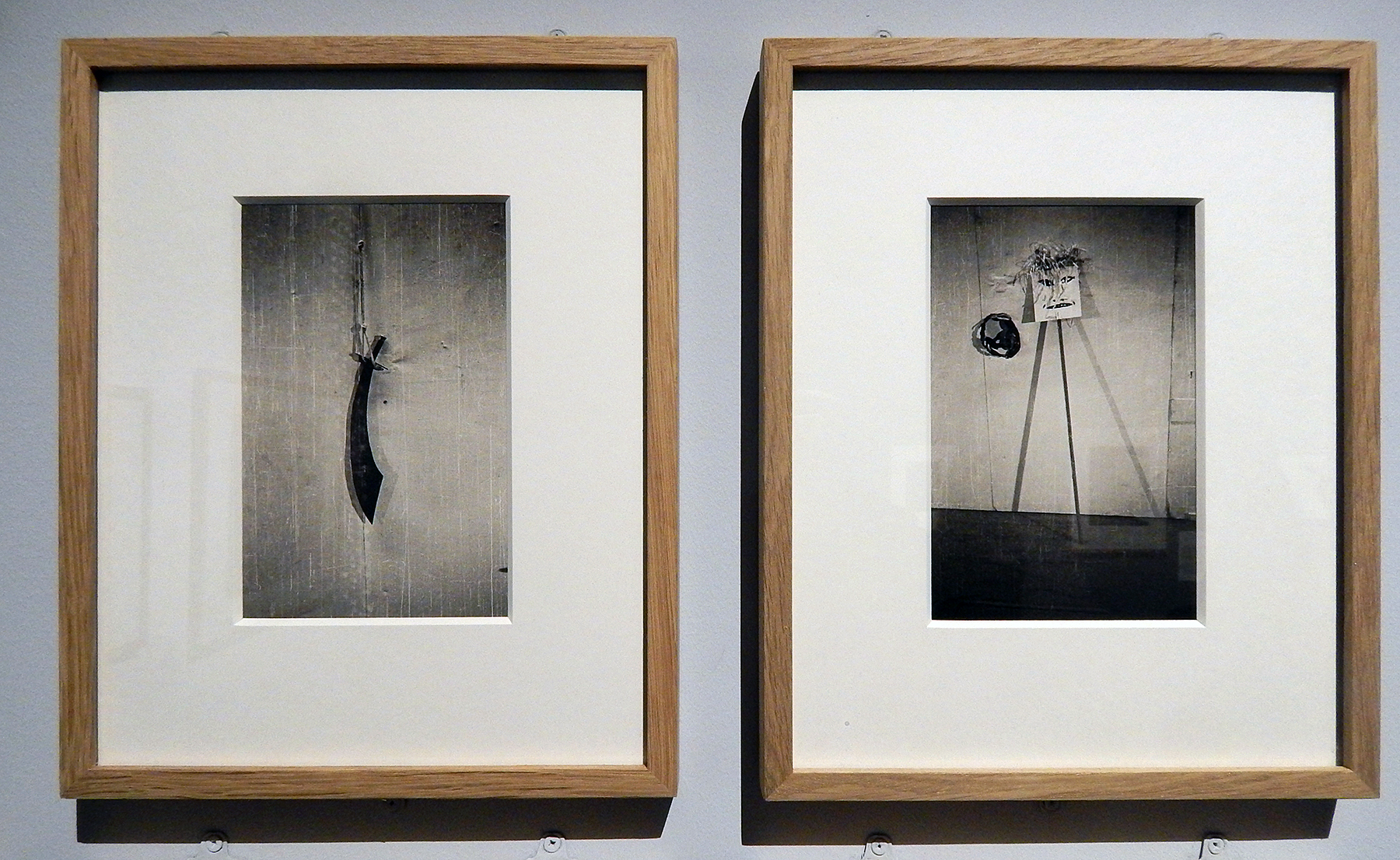

- Artistic props from Bertolt Brecht’s theater.

- Art that straddles the line between documentation and narrative -- photographs by Alan Sekula, film by Sergei Eisenstein, video art chronicling the global solidarity of dockworkers.

Alberto Korda, Don Quixote of the Streetlamp, Havana, Cuba (1959)

Hiroji Kubota, 'Black Panthers in Chicago, Illinois (1969)

While the expansive exhibition – taking two floors of the Jeu de Paume – cannot be encyclopedic, it provides a fairly exhaustive review of historical inputs (mostly from the past 200 years) for today’s radical artists to take stock. The weakest of the included artworks tend to be abstracted video and performance gestures on the idea of “rising up” – but even here there is some excellent work.

A sprawling installation divides the idea of “uprising” into five sections: “1. With Elements (Unleashed),” “2. With Gestures (Intense),” “3. With Words (Exclaimed),” “4. With Conflicts (Flared Up),” and “5. With Desires (Indestructible).”

Honoré Daumier, Les Femmes socialistes (1849)

Edouard Manet, Civil War (1871)

The result is an exhibition that mimics Fredric Jameson’s “elevator” – the literary device used in contemporary post-apocalyptic novels and films like Cloud Atlas. The viewer in Soulèvements jumps around in time – beginning with Goya’s Disasters, then pivoting between geographies and centuries and different rebellions and artists, arriving in the final galleries with the martyrs of the Paris Commune – flaneur-ing your way through two centuries of struggle. And at each point seeing commonalities (and differences) in the gestures and signs of resistance.

Jeu de Paume

It is worth noting – as an aside – that the Jeu de Paume was one of the main sites used during the Nazi occupation of Paris as a clearinghouse for stolen art to be shipped back to Germany. When Hermann Göring toured the site art was hung across its extremely long axis salon-style.

Questions remain, however, regarding some of the weaknesses of our historically radical art. Can we create and sustain radical art that is neither merely documentary but also eschews abstracting social and political content? One of the high-points of the exhibit for Emily Nathan was the series of “2002 C-prints by American artist Dennis Adams,” in which a

a red plastic bag, a newspaper—floats aimlessly against a sapphire-blue sky, lifted on a breeze. In their simplicity, these images present fleeting moments of liberation, in which an earth-bound object gets a chance to fly, and they feel like a small acts of revolution.

Gustave Courbet, Man in a Coat Standing on a Barricade (France, 1848)

Chieh-Jen Chen, The Route (2006)

While Adams’ photographs are undeniably beautiful this begs us to challenge the assumptions of the contemporary weak avant-garde. Why is the isolated and specific given more weight than the complex and interconnected? Adams’ photograph is saved, in fact, by its close physical proximity to the documents of actual social revolution in the exhibition hall.

And what gives artifacts of social revolution depth – beyond mere documentation – are the marks of individual subjectivity – like the graffiti scrawl of the Greek prisoners on fascist walls – and less dramatically the props of Brechtian theater and the paintings of Sigmar Polke.

Joseph Beuys, Thus Can the Dictatorship of Parties be Overcome (1971)

This begins to answer another major criticism of Soulèvements – from Joseph Nechvatal on Hyperallergic:

[C]an clear dialectical images of defiant gestures inspire civil disobedience, insubordination, or beneficial creative negation? Much of the raging and revolting energy (aimed often against multiculturalism, which is bizarrely labeled as elite) has been perpetrated by the fringe alt-right uprising, an extremist movement soon to be swathed in White House power. Can oppositional, dialectical images even sketch out some of the problems that need resisting? Perhaps images made of more ground than foreground could better convey how low-investment, low-demand, low-returns policies have set the stage for xenophobic racist populism. Following Trump’s triumph, France too seems poised to tear apart institutions and enable far right fever dreams to thrive. In the coming French election, the extreme right will most likely end as a choice, as well as a return to the austerity of Thatcherism. How can historical radical images, no matter how rambunctious, have any impact considering what planetary-scale computation and the movement of people has done to regional geopolitical realities? How can historical, representational imagery shake people’s subjective sense of future expectations and cause them to demand a rejuvenation of the left, rather than a mourning of its failures or praise of its past glories?

Charles Baudelaire, Gustave Croubet, Champpleury, Charles Toubin,

Le Salut public, n. 2 (1848

Props from the theater of Bertolt Brecht (1930s)

Guy Debord et al, Situationist International: New Theater of

Cultural Operations (Paris, 1958)

Nechvatal, of course, avoids the complicity of the neoliberal elites in allowing “multi-culturalism” to be “bizarrely labeled as elite” by using its terminology while pursuing policies that immiserate the majority of populations (of all cultures and races), thereby opening the door to neo-fascists. In electoral terms he mostly ignores rebellions of the “left” – such as the problematic but nonetheless actually existing Bernie Sanders primary campaign. And in activist terms he minimizes Black Lives Matter and Occupy. Let us also put to one side how Nechvatal mimics the bourgeois anti-historicism of the mainstream art world.

John Heartfelt, Cover art for John Reed's Ten DaysThat Shook the World

(Germany, 1927)

More centrally (for our purpose here) he misunderstands the role of radical art. If it inspires radical action all the better. But that is not its only purpose. Art is also a living document of human performances. If that performance is abstracted from social content it will reinforce bourgeois norms (and write the exploited and oppressed out of art history). A better rubric stems from understanding that art is both social and has a value inherent to itself as art.

Nechvatal is correct that “low-investment, low-demand, low-returns policies have set the stage for xenophobic racist populism” but wrong that “images made of more ground than foreground could better convey” such an attitude.

Annette Messager, The Pikes (1992)

Sigmar Polke, To Versailles, to Versailles (1988)

Annette Messager, The Pikes (1992) detail

We need both – and the brilliance of Soulèvements is that it gives us some ideas how to proceed.

Our work needs to be informed by the chaotic totality of the world – but it must also be shaped by the unique gestures of specific human beings. Our art needs the grand arc of history – but it also demands we see the marks made on our prison walls.

Voula Papaioannou, Prisoners' notes written on the walls of the German prison on Merlin Street, Athens (1944)

Voula Papaioannou, Prisoners' notes written on the walls of the German prison on Merlin Street, Athens (1944)

Voula Papaioannou, Prisoners' notes written on the walls of the German prison on Merlin Street, Athens (1944)

Soulèvements (Uprisings) on display through January 15 @ Jeu de Paume, Paris.

Adam Turl is an artist and writer based in St. Louis, Missouri (USA). He is currently in residency at the Cité internationale des arts in Paris, France. His most recent solo exhibition was 13 Baristas at the Brett Wesley Gallery in Las Vegas, Nevada (September-October, 2015). Turl co-operates a DIY art space, The Dollar Art House, in south St. Louis with Red Wedge editor and artist Craig E. Ross. Turl is also an art critic for the West End Word and an editor at Red Wedge Magazine.