A collection of anti-racist activist and photographer Syd Shelton’s work from Rock Against Racism has been collected together for the first time. Is this book a nostalgic trip to the bad old days of 1970s racial conflict or does it have something to offer a new generation fighting the changing face of racism in the 21st century? Maybe both?

Shelton’s starkly black and white photographs portray the sharp contrasts in 1970s Britain. National Front marchers and anti-racist crowds, the police and the youth on the street, the punks and Rastas, Sikh pensioners and black and white kids, the bands and the audiences.

Mainstream British culture was riddled with blatant racism – from sitcoms to school classrooms, football stadiums to police canteens, TV news studios to the Houses of Parliament. And as capitalism entered into its first crisis since the Second World War, cutbacks and unemployment spread, racism took a sharper and more violent form. The National Front paraded down High Streets waving flags and beating drums. Racists rampaged through “immigrant” areas of Britain's cities.

Racism and right wing politics then raised its head in the music world in the summer of 1976. Following David Bowie declaring that Britain needed a dictator, “Blues God” Eric Clapton openly spoke on stage in Birmingham praising racist Member of Parliament Enoch Powell: “I think Enoch’s right … we should send them all back. Throw the wogs out! Keep Britain white!”

Seizing the moment a couple of revolutionaries, who were also music fans, shot off a letter to the music press.

Come on Eric… Own up. Half your music is black. You’re rock music’s biggest colonist… We want to organise a rank and file movement against the racist poison music… we urge support for Rock against Racism. P.S. Who shot the Sheriff, Eric? It sure as hell wasn’t you!

The letter became a lightning conductor for music loving anti-racists across the country… and thus a movement was born. They didn’t wait for any political party to green light their idea or seek approval of left-wing dignitaries or celebrities. Over the following year the small group of activists started putting on gigs in London. Soon others around the country created similar events in such places as Brighton, Leeds and Glasgow. The movement subsequently spread to different parts of the planet and down the decades.

* * *

Shelton’s photographs illustrate the context in which this movement was born and raised. They portray the racists – both “respectable” and crop-headed – as their parades were pushed off the street by opponents and their openly violent side came to the fore. Shelton took street portraits of some of the skinhead mob who charged down East London's Brick Lane smashing windows in imitation of their forebears’ Kristallnacht. And the photos show the brilliant response of the Bengali youth leading a demonstration of some 7,000 people, carrying placards proudly declaring “Self-defence is No Offence”.

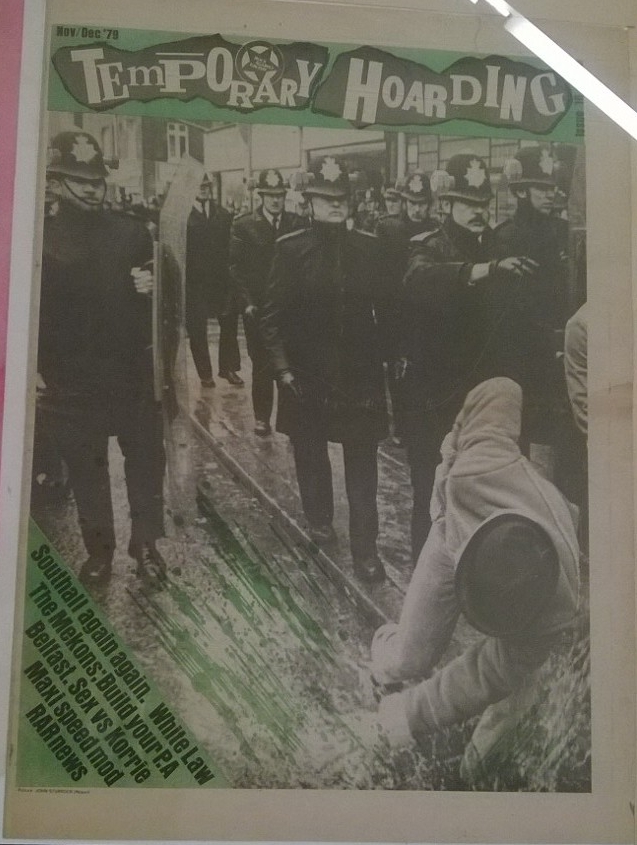

As well as the photographs, the book includes many reproductions of pages Shelton designed for RAR’s magazine Temporary Hoarding, including interviews with Johnny Rotten and the mother of a Irish Republican prisoner.

Cover for Temporary Hoarding at Autograph ABP exhibition (photo by Alexander Billet)

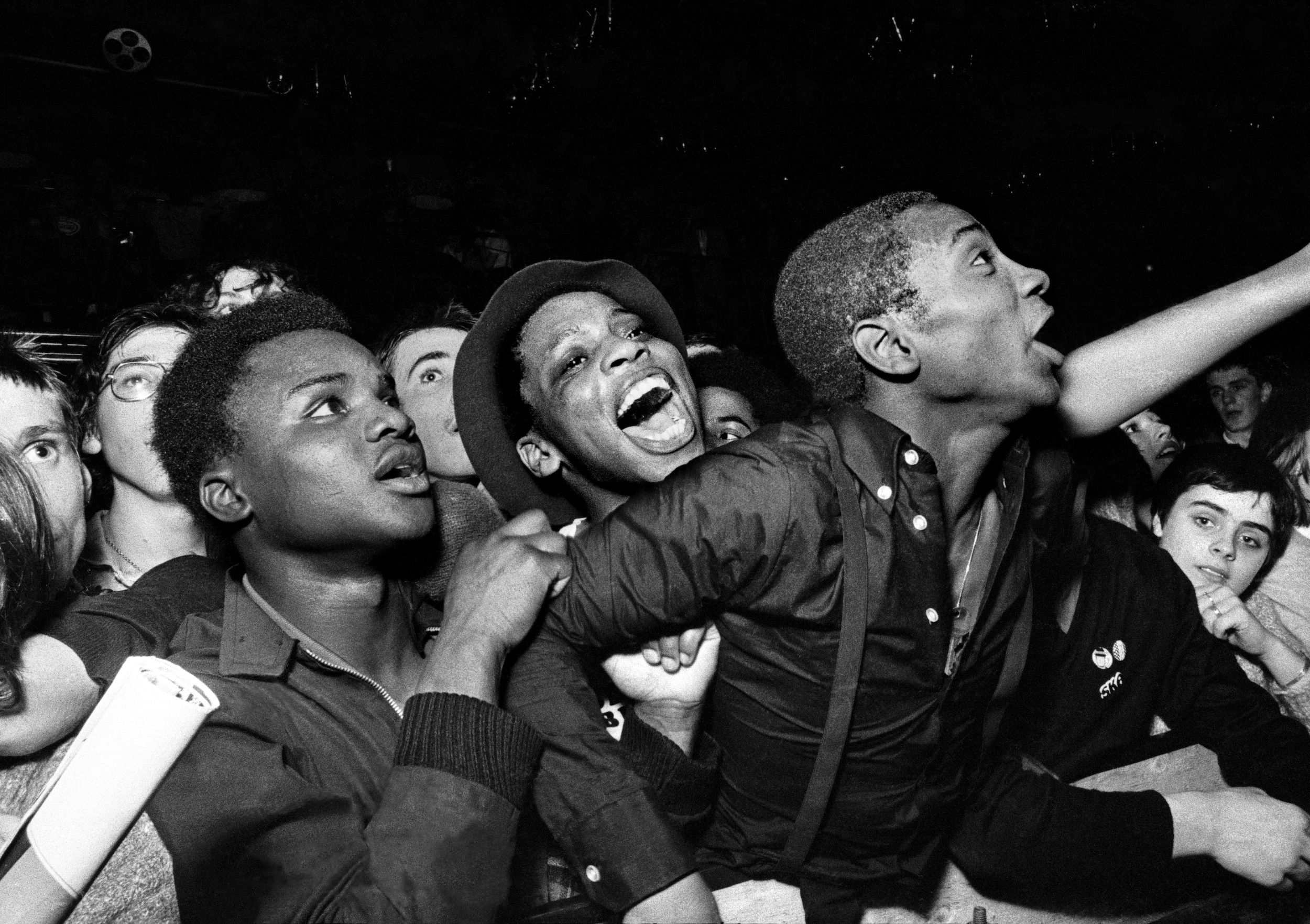

Until this book, Temporary Hoarding has been the main source for the various published accounts of RAR. However the lived experience of RAR for the many thousands involved in organising and going to the gigs and carnivals was somewhat forgotten. These photographs, the interview with Shelton and the essay by RAR participant (now cultural studies scholar) Paul Gilroy help to correct this and bring those experiences back to life. The images capture the excitement of attending gigs which were often special events – organized with the energy and enthusiasm of people who’d never done anything quite like it before.

Sometimes what made the gigs “special events” was the unnerving feeling that there was a good chance racists and fascists would arrive and have to be dealt with. This could involve anything from physically barring them at the door, to arguing with them to remove their racist badges and T-shirts. What also made these gigs special was because the bands sometimes wrote songs specially for or chose songs to cover for the occasion. The gigs would often finish with black and white musicians performing together on stage. The music was new and the sense of fusion was happening right in front of you. Reggae was not as new as runk, but it was often new to the many white ears there to listen…

There are many great photos in the book of the first Rock Against Racism Carnival 1978 which Syd not only photographed but helped organize. As is crucial to the democratic nature of his art, Syd's camera was pointed as much as the crowd and the participants as at the stage and the performers. This is how I remember the day.

In the middle of 70,000 young people who’ve come to rock against racism, me and two school friends join everyone around us singing, “Sing if you’re glad to be gay…” If we dared utter these words at school we’d be beaten up – which is what happened to two lads caught kissing in the bushes. There’s no sense of threat in this crowd today, singing along with Britain’s first openly gay pop star Tom Robinson. We’ve marched five miles from Trafalgar Square waving Anti-Nazi League lollipop placards to be part of this Carnival Against the Nazis and we will be leaving having expressed our solidarity with gay people. What an amazing day.

Militant Entertainment tour, 1978 (photo by Syd Shelton)

The Clash's Paul Simonon at the Carnival Against the Nazis in April, 1978 (photo by Syd Shelton)

Leaving the area is not so much fun. As hundreds of coaches pull away from Victoria Park handfuls of racists crawl out of pubs to heckle the thousands leaving. They are hardly brave to shout at departing vehicles, but the three of us have lost our gang of school friends so we slip past the racists searching for a bus home to South East London. Meanwhile skinheads in a pub in Deptford make one of the local punk bands play “Happy Birthday” for Adolf Hitler.

Gilroy, who wrote for Temporary Hoarding at the time, contributes a thoughtful and thought-provoking essay to the book. He writes:

…the insubordinate spirit of emergent Punk-dom had discovered common cause with the rising generation of young, black people who had learned by a different route that they too had no future in England’s pathological dreams of greatness restored. Power took flight.

* * *

In many ways the living embodiment of RAR's encouragement of collaboration and crossover between black and white, punk and reggae musicians was the Two Tone ska movement and in particular the Specials. A black and white band singing sharp-as-a-knife anti-racist songs, they were brilliant live and irresistible to their hordes of black and white fans for dancing to. They were what those of us putting on Rock Against Racism punk/reggae gigs had only dreamed about. And by 1981 they were so popular across the UK that they reached the top of the pop charts. And they did it with the most amazing song (one of their best-known) at the most perfect time.

This place, is coming like a ghost town

Bands won't play no more

too much fighting on the dance floor

Why must the youth fight amongst themselves?

Government leaving the youth on the shelf…

Riots burnt through what were known as black areas in Brixton, London and St Paul's, Bristol in early 1981 and then across Britain in July. As they did the Specials song could be heard blasting out of radios and clubs and parties. “Ghost Town,” describing the world of unemployment, racism, police oppression and a mini-civil war amongst the youth, hit the number one spot.

And they played what turned out to be the final 1981 RAR carnival the very weekend that the riots leapt from across the country like wildfire.

Photos in the book from the carnival capture a significantly different crowd from the first carnival – the mainly male and mainly white first RAR carnival in 1978 has become more female and more black by 1981.

Carnival Against the Nazis in Leeds, 1981 (photo by Syd Shelton)

It was also more a more street level youth-led campaign. As one of RAR group in Leeds says, “A group of about 20 of us – including five, like myself, who were teenagers – decided that we were going to put on a massive carnival. We phoned up The Specials and they agreed to headline. We had no money, but we had loads of credibility and support – and we put everyone to work. Every night gangs of kids would head out in our van and cover the city in posters, and during the day we’d be leafleting schools and colleges.”

Like the previous RAR/ANL Carnivals, the Leeds one started with a march from the city centre to a park in an “immigrant” neighborhood. And that's where the huge crowd bounced to their hi-energy, punk-influenced ska dance music with radical lyrics.

One aspect of RAR that the black and white photographs cannot capture is the vibrant colors of the badges, stickers, placards and even the neon sign that toured with RAR’s nationwide Militant Entertainment tour that staged gigs in all the towns where the NF looked like making headway in the 1979 election. As Gilroy puts it, there was “an unprecedented connection between the spirit of political dissent and the novel ways in which it was being communicated and rendered.”

This is affirmed in the interview with Shelton in the book. A key RAR activist and designer as well as a photographer, he describes his experiences of the period, and sums up his approach to photography as observing “like an urban fox.”

“In collaboration with UK reggae and punk bands,” Shelton concludes, “RAR members took on the orthodoxy through five carnivals and some 500 gigs throughout Britain. In those five years, the National Front went from a serious electoral threat into political oblivion.”

Or, as RAR’s David Widgery put it, “the great thing about RAR was it’s a way of having a revolution without stopping the party.”

* * *

Syd Sheldon, Rock Against Racism. London: Autograph ABP, 2015. 188pp. £30 hardcover.

This is an expanded version of an article that appeared at the website revolutionary socialism in the 21st century.

This review appears in Red Wedge No. 2, "Art Against Global Apartheid," available for purchase at the Red Wedge shop.

Colin Revolting was in his first punk band in 1977 while still at school in London. Despite being from a revolutionary socialist family it was punk rock and fighting racism that drew Colin to his own revolutionary politics. A life of agitation, both cultural and political, continues to this day with the theatre company Revolting Peasants. More of Colin‘s tales of political protest can be found at the Guardian and revolutionary socialism in the 21st Century.