Robots of the world! The power of man has fallen! A new world has arisen: the Rule of the Robots! March! – Karel Capek

I

The robots have arrived – sort of. It’s only a matter of where one looks. If one were paying attention to the Oscars this year, it would have been hard to miss the most famous robot trio of all time as they arrived on the opulent stage of the Dolby Theater. Ahead strutted in the pleasingly neurotic, bronze figure of the linguist, C-3PO, with his short, stout, and sassy mechanic mate R2-D2 close behind, and bringing up the rear the white-orange ball of a droid named BB-8, who made its debut in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, released this past December. When R2-D2 beeps that C-3PO forgot the tickets to the ceremony, the latter retorts: “The ticket was your job, nitwit.” When told that he looked somewhat like the Oscar statue behind them, C-3PO declared that it looked like him. “How do you think we made it this far?”

Thanks in no small measure to Hollywood – in particular the Star Wars space saga, the maiden episode of which hit theaters in May, 1977 – robots have become part and parcel of our popular culture and commerce. On the silver and plasma screens, we’ve met robots that are riotously contrasting in shape, size, and intent. They run the entire gamut, from heroic to villainous, cunning to caring, terrifying to trustworthy. On store shelves, we’ve seen them as tea infusers, cookie jars, action figures, cushions, desk lamps, nutcrackers, and what not.

In 2010, even the Swedish vodka maker Svedka couldn’t resist cashing in on their swelling popularity. To peddle its product, it ran a campaign with the theme “R.U. Bot or Not?” featuring a so-called “fembot,” a sensual female robot from the future. The copy on its print advertisement read: “Make your next trophy wife 100% platinum.” Next to it stood a curvaceous gynoid. The spirit, may, as she claimed, have been “Voted #1 Vodka of 2033,” but it our time, it raised quite a few feminist eyebrows on grounds that it was offensive to women.

II

Long before the robot was a toy or a vacuum cleaner (think: Roomba), it was a metaphor. It all began in the early 20th century, with R.U.R., a paradigm-shifting, dystopic play by Karel Capek that birthed the very word “robot.” Written in 1920, it premiered in January the next year in Prague. A hard-edged satire of the political zeitgeist of that age, it begins in the office of Rossum’s Universal Robots (the titular “R.U.R.”), a secret factory on a “distant island,” somewhere off the coast of continental Europe, in the business of making “artificial people.” When a compassionate young lady named Helena Glory drops in with a request to tour the plant, its general manager Harry Domin is happy to show her around. Narrating the corporate lore, he tells her that in 1920 Rossum, a physiologist, had traveled to that location for the purpose of studying marine fauna. During the course of a series of successful experiments there, he made a startling discovery: a formula for making all living organisms.

Karel Capek

The roots of man’s desire to create life go back to the mists of time, to Greco-Roman antiquity. But owing mostly to science-fiction, this “prehistory” of robots is understood to reach only as far back as the 19th century, to an industrial age smoggy with chimney smoke, and noisy with the clangor of pistons and bellows. The most famous example of that is Mary Shelly’s grotesque golem Frankenstein, born in 1818. In H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau, published in 1896, Moreau, a biotechnologist of his day, builds beings that are half-human, half-animal. What’s notable is that such men who wish to tinker with nature are mad geniuses and see themselves as bold men of science. Their “creations” are therefore “born,” typically, in a petri dish or a test tube, as accidental amalgams of exotic powders, solutions, and emulsions.

III

In R.U.R., the cradle of such synthetic life is still a glass beaker, but the colloidal mess that is the seat of consciousness, snatched away from a laboratory bench and placed on the moving assembly-line of a sweatshop. Old Rossum, a die-hard atheist, had set out to make man, with an ambition to replacing god. But his son, an engineer, was driven by a different dream – a dream to be rich, a mogul, an industrial god. He wanted to crank out, not man per se, but his simulacrum, and that too at an accelerated rate. His “goods” had their bones, muscles, and organs put together on conveyer belts, just like Ford’s Model T. This is Capek’s nod to Taylorism, an early capitalist management theory, with its clinical focus on streamlining workflow and maximizing productivity.

Not only is the “human machine” “too expensive” the junior Rossum thinks, but it also has many bells and whistles (moods, emotions, aspirations), which come in the way of its being the most efficient worker. And so he invents the “robot,” an abridged edition of man. Sure, he’s “mechanically more perfect” than man, and has an “enormously developed intelligence,” but he has “no soul.” He has little demand but to work fiendishly. Capek’s models are not mechanical life-forms, but come closer to the contemporary notion of a clone, for they are biological machines that could well be mistaken for humans, much like the “replicants” in Blade Runner (1982) or the “Cylons” in Battlestar Galactica (1978). “Robot” was a coinage of Capek’s brother, Josef, a cubist painter who worked as a cartoonist for the daily Lidové Noviny. In Czech, it means “forced labor.”

Self-portrait of Josef Capek

IV

One of the earliest references in modern literature to what appears to be a “robot-like robot” is found in a children’s book released in the U.S. a little over a decade before R.U.R. In Ozma of Oz (1907), the fourth book of the “Oz” series, L. Frank Baum presents a “mechanical man” named Tik-Tok (different from the more recognizable Tin Man). He “thinks, speaks, acts, and does everything, but live.” A low-maintenance fellow, he simply requires to be wound up every now and then, and is guaranteed to work perfectly for 1,000 years. He’s portrayed as a helpful playmate to Dorothy Gale and her friends. Not as a servant.

However, it’s not until R.U.R. that there’s a dramatic change in the raison d’être of the man-forged life. He exists not for himself, but in serfdom to his “creator,” with no destiny other than as the doer of tasks which are either too dangerous or too dull and repetitive for humans to perform. They are the hewers of wood, the drawers of water as well the typists and the clerks and the waitrons. There are, after all, “robots of finer and coarser grades,” explains Domin.

The motive that drives the robots’ clockwork production is purely economic. They make the best workers, being the cheapest. Each costs $150 to build, and 0.75 cents an hour to operate. By becoming the labor pool in mills, foundries, and plantations around the world, these laborers, themselves factory products, in turn, drive down their employers’ costs. Domin gushes that in the near future, they’ll produce so much of everything – from corn to cloth – that “things will be practically, without price.” Not only will that benefit the consumer, but also liberate the producer from the agony of toil. The enslavement of man to man will cease. As all work will be done by “living tools,” as described by Aristotle in Poetics, everyone will be free to pursue as he pleases, without worry, perpetual and protean.

But “the instrument of labor, when it takes the form of a machine, immediately becomes a competitor of the workman himself,” writes Karl Marx, in Volume I of Capital, under the section, “The Strife between Workman and Machine.” The expansion of capital, by means of machinery, is directly proportional to the number of the workers, whose means of livelihood have been destroyed by that machinery.

Poster for an American Federal Theatre production of R.U.R., circa 1930s

The narrative of a revolution in which robot overlords turn humanity into a subaltern race, ushering in a reign of cold terror, can trace its roots in the “class struggle” between man and machine in R.U.R. Capek’s tale culminates in the “revolt of the robots” – again, a phrase, which originates in this drama – because it’s the robots that are, in a Marxian sense, the lowest rank of the proletariat as they receive no wage at all, for their sweat and tears. When Helena proposes that they be paid, she’s scoffed at by a manager. “And what would they do with their wages, pray?” he asks.

V

Capek was pouring out his creativity in a climate red-hot with the recent Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. In 1917, two revolts swept through that nation, bringing to an end its imperial rule, and setting in motion political and social forces that would result in the eventual foundation of the the Soviet Union. In March, angry demonstrators took to the streets of Petrograd (now, St. Petersburg), then capital of Russia, clamoring for bread. What began as civil unrest quickly erupted into a revolt so widespread that it toppled Nicholas II, the last czar. Discontent simmered until it exploded in the next round in November, with a far greater ferocity. Red guards stormed the Winter Palace (now the Hermitage Museum), and seized power from a new government.

In R.U.R. the robots begin their mutiny by seizure of all firearms, telegraphs, radio stations, railways, and ships. There’s a historical parallel. From 1900 until World War I broke out in 1914, almost all of Europe reverberated with the sound of locks being bolted, keys being turned, and union workers standing in pickets, holding placards, demanding fairer treatment and better wages. In 1902 the metal workers in Barcelona declared strike; in 1903, the railway workers in the Netherlands; in 1905 the coal miners in Germany’s Ruhr Valley called for stoppage of work. These incidents spread rapidly and radially, across different sectors – coalfields, railways, docks, government building. Rosa Luxemburg, in her book The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions (1906) described it as a “broad billow over the whole kingdom (of capitalism).”

VI

R.U.R. gave robots a bad name. But Capek, who was a humanist and champion of workers’ rights, had only intended to draw attention to the sorry state of the working class. To him, the robot was the workman. He voices his own perspective through Helena, who arrives on behalf of the Humanity League with a plea to ensure that the robots are treated as equals, indeed, to liberate them.

Closer to the play’s dénouement, she jogs her husband’s memory about an event that took place in their past in America, in which the blue-collar men rose in protest against the machines. At the time, the U.S. government had retaliated by arming the entire cadre of disgruntled robots, turning them into a legion of lethal soldiers against its own people.

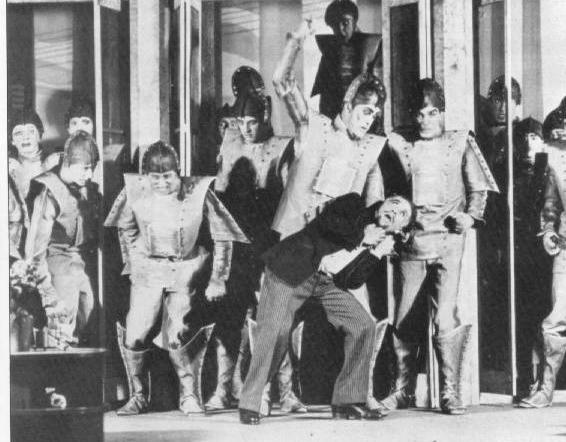

The robot rebellion in a Prague production of R.U.R.

Capek makes it quite clear that the robot population runs amok not because they have suddenly become more technologically superior, but out of a realization of their own deplorable conditions. They stage a coup d’état against their masters and reset the power structure. When the two sides go to war, robots and humans stand in the ratio of 1,000 to 1. By the 1960’s, humans are all but extinct.

VII

Isaac Asimov, pioneer of robot literature and the coiner of the term “robotics,” was a toddler when R.U.R. had its American première on Broadway in October of 1922, where it ran for nearly 200 performances to wide acclaim. (In a much later essay, he wrote that he didn’t quite take to it.) By the time he embarked on his literary career, the public perception of robots had taken a sour turn. They were feared objects.

Tired of their portrayal as evil creatures that turn against their makers, he opened our minds to a world where robots are an affable breed that guarded humans against danger. Throughout the 1940s, he penned a series of robot stories, which would coalesce into the well-known single volume I, Robot, published in 1950. “Robbie,” the yarn that opened the collection, is about a sweet friendship that develops between a little girl named Gloria and her family’s eponymous domestic bot. When he leaps to rescue her from the path of oncoming traffic, he earns her parents’ trust. During the same period, Asimov also laid down a code of conduct for machines, a framework for governing the interaction between humans and robots, known as the Three Laws of Robotics.

- A robot may not injure a human being or through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence, as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Later, he inserted a Fourth or “Zeroth” Law, which outranked the others: “A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.”

Couched in these directives is the assumption that robots are intrinsically capable of hurting humans. But Asimov formulated them so as to convince people that robots weren’t innate killers.

Interestingly, both Capek and Asimov had a tender take on the robot. To Capek the robot was a slave, made of flesh and blood; to Asimov it was a technological being, made of chips and circuitry, who was a human ally.

VIII

Data from the International Federation of Robotics – a non-profit that protects the interests of the robot industry – show that today, worldwide, for every 10,000 employees, on an average, there are 66 robots. In South Korea, that density is about 400; 300 in Japan; 290 in Germany; and 160 in the U.S. The apocalypse depicted in R.U.R. is far from reality, assures one of the I.F.R.’s brochures. The loss of employment from automation, though, will only fuel fear of robots.

In response to a spate of labor troubles plaguing Chinese factories, Willy Lin, the managing director of a Hong Kong-based knitwear company, told Businessweek (in the piece, “Using Propaganda to Stop China’s Strikes,” published on December 15, 2011) that after he’d added new Japanese knitting machines at its Dongguan sweater factory, he’s reduced the number of workers from 80 to six. “All the headaches, the riots… gone,” he told the paper. “Machines don’t complain about their salaries.”

Sharmila Mukherjee contributed research for this article.

Red Wedge No. 2, "Art Against Global Apartheid," is now available for pre-order. If you liked the above piece, support Red Wedge by ordering a copy or taking out a subscription.

Alakananda Mookerjee is a New York-based science writer. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Red Fez, The Indypendent, and elsewhere.