There is no getting around the popularity or cultural clout that both Afropunk and Afrofuturism have in contemporary culture. It’s been over ten years since James Spooner’s film on Afropunk came out, the website that bears its name is visited by hundreds of thousands each month, and the yearly festival recently expanded from Brooklyn to Atlanta and will soon be making its way to Paris. Afrofuturism, for its part, has become quite trendy in certain circles, with advertising companies attempting to cash in on its aesthetic. It is not difficult to see its influence in a growing array of artists.

There is a certain line of argument that emerges when subversive cultural modes gain a critical mass of popularity. It is only natural to anticipate their dilution, their spreading to the point where any of their attempts to push the mainstream in their direction is met with the expectation they've been sanitized. When an artist loosely associated with Afropunk who is hailed by the record industry as the new face of Afrofuturism is now lending her presence to the sale of soda, you know something very complicated is happening. The temptation to start over is inevitable. I'd rather ask a question, one borne out of continuity rather than starting from scratch: What comes next?

A key might be found for both aesthetics in acknowledging the endless ways in which the two crossover. Though distinct, they are very much linked, both historically and in contemporary contexts. What’s more, to look at so many artists associated with one movement is to see or hear the impacts of the other. It is difficult to look at the magnificent, colorful stage presence of a musician like Ebony Bones, with her wild mashups of post-punk, Afrobeat and new wave and deny that what one is witnessing is both sublimely punk and in the same breath futuristic.

Black art matters. It always has. In fact, in terms of United States, there would be no such thing as “American culture” if not for the voices of Africans and their descendants. It stands to reason then that the pillars of neoliberal politico-culture can, have been and will be shaken when ordinary Black workers and students put themselves in motion. In turn, this explains how Black Lives Matter is setting the tone, its reverberations bouncing between the streets and performance spaces an effort to re-center Black and African voices.

Calling this syncretic Afrocentrism “new” is not entirely correct. Both movements use iterations and signifiers whose meaning is unique in their own time, but there are cues all over – even in the new – of a past un-reckoned with. In some ways that’s the point: people of African descent have been central in both punk and broad schools of artistic modernism since their beginning. They have been overlooked – oftentimes their contributions stolen or neglected – and they deserve to be brought to center-stage. Afropunk and Afrofuturism both have a fairly conscious relationship with temporality and history, a sense that acknowledgement of past participation ensures a certain amount of autonomy in the present and future.

In the case of punk’s more expansive definitions, it’s not so much about the leather and same three power chords as it is about the shattering of conformity and acceptability in the broad name of freedom. Futurism similarly so. Though here is a complication: taken on sheer aesthetic affinity, Afrofuturism bears less in common with its World War I era counterparts in Russia or Italy and far more with the more expansive, mind-bending, space-altering tropes of Surrealism. Said Ytasha Womack in her piece on Black Future Month for Red Wedge last year:

Afrofuturism differs from traditional science fiction in a host of ways. For one, it values mysticism and nonlinear thought. The aesthetic embraces a fluid relationship between the past, present, and future, with artistic representations and poetics speaking of all three as one… While the futurist of the early 20th century hailed all technology as progressive, Afrofuturists do not. In fact, race is referred to as a technology. The creation of race – an effort to justify the transatlantic Slave Trade and create a caste system defined by color and enacted through law and violence – is explored as a technology in Afrofuturism.

All of this smacks highly of the dissident history of Surrealism – including the Europeans who are simplistically credited with “originating” the movement. Breton, Peret, Cahun, Tzara, Naville, Toyen – communists all of one kind or another, and often at odd with “official Marxism” in their unconditional support for the Rif uprising in Morocco and the inspiration taken from the Maroon settlements of escaped slaves. Robin D.G. Kelley, in his Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, suggests that much of what cohered into Surrealism in the 1920’s – its rejection of positivist notions of “progress,” the blazing hopes of social revolution and unconditional freedom of the mind, body and spirit – “were present in Afrodiasporic culture before surrealism was even named.”

There is, therefore, a through-line from Surrealism to punk, roughly butting up against Dada and Futurism proper, through the post-war years and into Situationism. The Situationists, it has been well-documented, had a massive influence on the aesthetics and slogans of punk’s early years, though they were far too quick to drift into a kind of nihilism rather than evince the kind of unfettered hope and creativity that was scrawled on the walls of Paris in ’68. On the other end, Michael Lowy’s Morning Star reconnects the dots between Situationism’s dark, gothic Marxist ethos with that of its Surrealist forebears. The lines on the map do not lie.

Cutting through this line, however, is a very real erasure. Surrealist histories far too often overlook the influence of writers like Pierre Yoyotte, Suzanne and Aime Cesaire, bending the movement into the same Eurocentrism that shapes our view of Futurism. That Surrealism saw itself as in constant conversation with the Negritude movement was quickly pushed aside, even by the former’s direct inheritors. A recent article by Andrea Gibbons in Salvage charts how the Situationists failed to confront the way in which colonialism had shaped the everyday life they wished to revolutionize. The racism of Malcolm McLaren and Bernie Rhodes – the two Svengalis most credited with ushering Situationism into punk – is well-documented. (And there is something telling about the fact that while the implosion of the Sex Pistols allowed McLaren to move onto uncomfortably Orientalist projects, the Clash’s move to drop Rhodes allowed them in turn to engage more meaningfully with reggae, soul and hip-hop. This is no coincidence.)

That the influence of Blacks, Africans and Caribbean people are viewed as episodic rather than a constant in modern culture – pushed to the margins in real-time and retellings of not just artistic movements but history generally – reflects just how deeply capitalism is interwoven with the history of colonialism and racism. It also reveals that Janelle Monae’s appearance in a Pepsi commercial is perhaps not as much of a stabilized co-optation.

Janelle Monae's Pepsi commercial

“By a kind of perverted logic,” wrote Frantz Fanon of colonialism, “it turns to the past of the oppressed people, and distorts, disfigures, and destroys it. This work of devaluing pre-colonial history takes on a dialectical significance today.” This dialectical significance is always being taking advantage of by the culture industry. It is a move very much in tune with the Congressional Black Caucus’ apologia for Clintonian policies of mass incarceration and welfare reform, a marching of the civil rights movement’s legacy into the stables of safe nostalgia rather than active resistance. When in fact the meaning of this legacy is far more contested now than it has been in some time. Will Janelle Monae’s Pepsi endorsement confuse her fierce and unapologetic demand that we “say their names”? What about her recent alliance with Teach For America? Was Beyoncé’s invasion of the Super Bowl with a roughly Futurist “21st century Panther” iconography a potential boon for Black radical consciousness? Or was it just the move of a very savvy Black capitalist? Can all of these be true at the very same time?

These questions are already much discussed, but they remain unanswered. My personal take is that the symbolism of the art is quite autonomous from the artist’s class position. But a clear answer in either direction relies most on what happens now, what continues to happen in the coming months. For sure, there are cynics at work here, looking to herd anything remotely subversive into the stables. At the same time, it would seem worth noting that, as Lenin wrote, “the capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them.” Pepsi, Teach For America, the organizers of the Super Bowl halftime show; all of these are interests that seek to twist the meaning that history has given to certain sounds and images.

Which is precisely why it is counterproductive to look at the movement of history and aesthetics as just “one thing after another,” haphazardly unfolding, with anyone able to take any moment out of context, using it however they please. Far more radical, dynamic, and useful is a view of history that is constantly and perpetually culminating in new moments, each one rolling forth and crashing up against the next, in turn reshaping it and disorienting old meanings with the infusion of new ones.

“It is not that I have no past,” Samuel Delany once wrote. “Rather it continually fragments on the terrible and vivid ephemera of now.” In short, the past’s meaning is made and remade, and which present force can grab its momentum will ultimately make the future. This, in a nutshell, is probably the most significant lesson that I – an anti-racist who is admittedly un-impacted directly by the vicissitudes of American racism – have gleaned from both Afropunk and Afrofuturism over the past several years. The very word “Afrocentrism” implies a completely different concept of geography and temporality than the one we are so used to under late capitalism and its segregatory logic. At a very basic level, what radicals and artists alike are pursuing is a different relationship with our space and time.

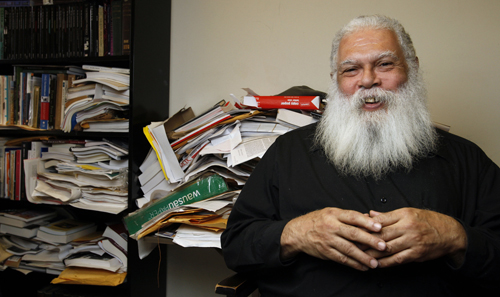

Samuel R. Delany

In the forthcoming print edition of Red Wedge will be a roundtable featuring Robin Kelley, Walidah Imarisha – editor of Octavia’s Brood – and Jonathan Horstmann of the queer, Black “futurepunk” group BLXPLTN. All three provide somewhat different but incredibly useful insights into the history and present of the Black radical imagination. Without giving away the entire roundtable, all three participants, even in their divergences and coming from various angles, provide an inspiring schema of why the history of this radical imaginary has a bearing on its present. Here is a brief clip of Imarisha’s words, echoing Kelley from earlier:

I think these pieces have always been there, these are just the names we have hung on them at this juncture. This is ancient knowledge, whether it is the non-linear way different African cultures thought of time as explored in the anthology Black Quantum Futurisms, or Sun-Ra’s Saturn ciphers. We have always manifested these ideas, whether it was WEB Du Bois writing science fiction in his short story “The Comet,” or Bad Brains created hardcore. I grew up as a Black person listening to punk music and reading science fiction, and it felt to me these were the places where I had the opportunity to claim myself and make of me what I would. Where I could step beyond what I was being told I was by the larger society as a Black woman, and instead decide for myself who I will be.

Art plays a unique role in all of this, in the mediation of a how a human being is both shaped by time and in turn may shape it themselves, carving out a place in which they might see themselves. It is eminently dialectical, a reminder that “meaning” is a battle ground in which past and future are ideological weapons.

It is also a reminder that, while mainstream floodgates may choose to let through moments of subversion with the hope that they will be sterilized in the process, the potential for those gates to be pushed or pulled always remains with the grassroots. Yes, there are the Monaes of the world, often making brilliant art that can inspire as easily as it can frustrate. But there are also the BLXPLTNs, the Ytasha Womacks, the Ebony Boneses, Walidah Imarishas, the Yohannes Felekes and Miguel Llansós, the HXLTs.

Perhaps it is then more fitting to sum up this tempestuous radicalism not as nostalgia but as its polar opposite: anticipation and uncertainty. Recently an unpublished manuscript of WEB DuBois’ was discovered: a short science fiction story called “The Princess Steel.” It is believe to be his earliest-known story and is being referred to as a “foundational” text of Afrofuturism. The text has yet to be published. Science fiction fans, scholars and anti-racists are all curious about what it might contain. What can American history’s best-known Black socialist, dead for more than fifty years, tell us about our vision of the future? And what will our present discovery of that do to change it? These are questions we have yet to answer. Revolutionary potentials hang off the end of them.

Alexander Billet is a writer, poet and cultural critic living in Chicago. He is a founding editor at Red Wedge and is a contributor to Jacobin, In These Times and other outlets. Follow him on Twitter: @UbuPamplemousse