What’s the best thing about Gary Ross’s Free State of Jones? It is clearly a film that will rile the “All Lives Matter” crowd. For conscious white-supremacists and “color blind” racists alike, the portrayal on screen of a white Southerner – an army deserter – in league with runaway slaves in defiance of the tax man, the war machine, and the system of human bondage, amounts to a giant slap in the face. And it should be. But Free State of Jones is much more than that. Here we have a mainstream film about a band of rebels in conscious opposition to economic inequality and horrendous racial injustices. What's more, they are led by a proponent of a utopian, agrarian-socialist vision of society.

This is exactly our kind of discourse. Socialists aim to shake things up and that means shaking people up. What’s troubling is that for some of our friends on the Left, the film is rife with political faux-pas from “mansplaining” to “white-saviorism” and falls well short of what is needed. Such critiques miss the mark, both in terms of what sort of movie Ross has made, and what sort of art is demanded by our moment in history.

Some have decried Ross for taking liberties with gaps in the historical record in order to spin a particular narrative. We maintain that film (and art in general) should allow for and even encourage creative interventions in their interpretations of historical events rather than simply producing uninspired straightforward re-tellings.

This is not a perfect film and there are certainly criticisms to be made, as there are of any piece of art. But if we are to engage them effectively, we’ll need to first establish what we want from art at this time. Do we want films to just tell a well-documented story? Or do we want them to inspire hope and dare people to take a cue from the heroes on the screen? The dismissals of the film that we’ve read, from the hatchet jobs thinly-veiled as faint praise, to those that assert that Free State of Jones is just another problematic narrative which upholds the white supremacist status quo, are all informed by what’s broadly labeled “identity politics.” These politics are useful insofar as they place oppression and oppressed people at the center, but are far too limited to serve as practical politics of liberation.

We think that Free State of Jones deserves a fair hearing and an enthusiastic defense if for no other reason than that the director’s expressed purpose for making it was to help debunk some long-established myths about the American Civil War. There’s a lot to unpack and explain here, but first we should say something about the subject of the film.

Some basics

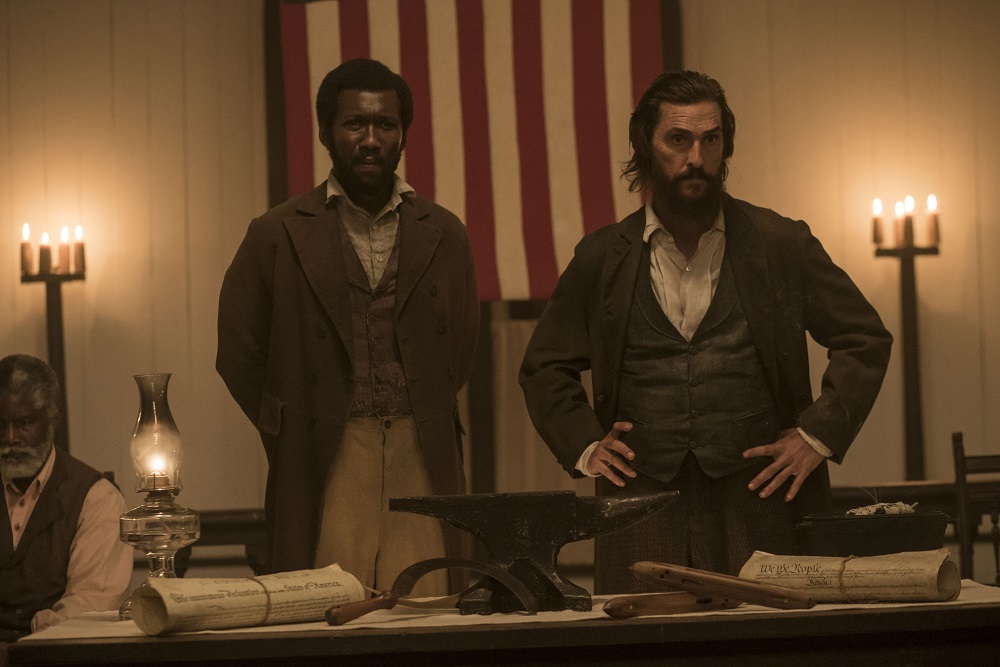

Free State of Jones tells the story of a “Southern Unionist” rebellion in Mississippi, mainly in Jones County, during the American Civil War. Jones County was mostly populated by poor farmers who owned no slaves and had elected an anti-secession delegate to Mississippi’s Secession Convention in 1861. It isn’t difficult to see how such an environment might bring together army deserters and runaway slaves. From 1863 to 1865, the Knight Company, so-named for its elected commander, Newton Knight (Matthew McConaughey), clashed with Confederate troops, assassinated government officials, raided military supply lines, and distributed expropriated goods to the poor on at least one occasion. By 1864, Confederate control was nonexistent and the titular free state was declared. The program of their liberated territory enumerated a radically egalitarian set of principles which provide reason enough for the film to exist. And it is the scene during which these principles are declared and affirmed by the people of Jones County that the greatest value of the film can be found.

Newton Knight.

Knight was said to have been a moral opponent of slavery since before the war. It certainly suits us just fine for the hero of the story to have that strong of a moral compass but since there are neither records nor legends of anti-slavery activity on Knight’s part, we’re left taking his family at its word. However, like John Brown before the war, and James Longstreet (the Confederate general turned Reconstructionist), Newton Knight is someone who need not be recast as sympathetic for the purposes of 21st century storytelling. While McConaughey's portrayal of the man as a principled anti-racist may be looked upon with skepticism, we know that after the war, Knight was a member of the pro-Reconstruction Union League and a defender of the embattled new civil rights of the Freedmen. We also know that he and his partner Rachel (Gugu Mbatha-Raw) – a former slave who had both saved Knight’s life and joined the rebellion – stayed armed and on guard against white-supremacist vigilantes the rest of their lives.

Against the “woker-than-thou”

In this light, we find many of the aforementioned “woker-than-thou” film reviews to be wholly unfair and frankly, quite unfounded – not to mention demoralizing. Two reviews we encountered are particularly egregious in their nearly wholesale denouncement of Free State of Jones. The first is Eileen Jones’ review in Jacobin and the other is Vann R. Newkirk’s in The Atlantic. Jones’ piece comes off as a brag about how much more she knows about the Civil War than everyone else, save for Eric Foner, with accusations of epic mansplaining for good measure. Meanwhile, Newkirk’s is practically the poster child for the most unproductive and divisive aspects of ultra-left identity politics.

According to Eileen Jones, Gary Ross has given us little more than “a terrible film about a great book” and an even more fascinating historical moment – though, according to Jones, all of Ross' adaptations of great books are trash. Jones writes that it plays like “the kind of film that gets screened in junior high schools – earnest, lumpy, and plodding, full of stodgy subtitles reporting what year it is and which national events will shortly have repercussions for our heroes in some trite illustrative scene.”

These subtitles signaled important historical events, without which an audience unfamiliar with Civil War details would have had to make quite a few educated guesses. Moreover, we think it is necessary that films of this sort make some indication about the jump from one time and place to another. Free State of Jones spans both the Civil War and Reconstruction periods, and even skips ahead to the 20th century in order to make a point about the continuing legacy of white supremacy. Perhaps this scope was a bit too ambitious, but even the well-read moviegoer should be informed that the year has changed, even on a dramatically slimmed down timeline.

Rachel Knight.

The most maddening of Jones’ critiques, however, is the accusation of Knight’s “epic mansplaining”. Jones writes: “There’s a cringeworthy scene where he teaches Rachel to read the words on a barrel of a Remington rifle. Then, in an act of epic mansplaining, he teaches her to shoot it. It’s ghastly if you’ve read about the actual Rachel Knight or seen the photograph that shows her to have been a remarkably tough and independent woman you’d be foolish to mess with.”

Here Jones seems to be implying that “remarkably tough and independent” women must also necessarily know how to fire a gun. There’s no doubt that Rachel was a badass whose remarkable skills and extensive knowledge of herbalism, the Mississippi swamplands and her cunning ability to steal food from the very plantation that enslaved her are what “kept Knight’s fledgling community going” as Jones puts it, but does that have to mean she also knew how to use a rifle? Short answer: No. The long answer is twofold: 1.) It is very unlikely that slave-owners taught her or any of their slaves how to use any sort of firearm. For obvious reasons. 2.) Her badassery is not diminished because Knight, a soldier, taught her something she didn’t know.

Jones does, however, make one valid critique about the film as a piece of art that falls short of being as impactful or entertaining as perhaps it could be. Jones argues that Ross “keeps jumping the narrative ahead to catch up with Knight’s grandson in the 1940s.” While the purpose of this time-hop (Knight’s “quarter-black” grandson’s miscegenation trial) is clear, Jones is correct that, “with all that’s going on in the Civil War and Reconstruction eras in an already overburdened movie, it’s maddening to have to keep visiting the twentieth century.” This is about as fair and solid a critique as Jones makes in her entire review. Perhaps the courtroom battle could have opened the film’s narrative, thereby providing a lens through which the audience could then watch the uninterrupted tale of Newton Knight. Or perhaps the time-hop between centuries could have be omitted altogether.

Meanwhile, Newkirk’s unsparing criticisms of the film center around (and are confused by it seems) his profound disapproval of McConaughey’s portrayal of Newton Knight as a hardcore anti-racist radical (which he was) committed to uniting poor disenfranchised whites and runaway slaves in the fight against the wealthy white-supremacist Confederate south.

“Wait, how is this a bad thing?” we wondered. Isn’t it a decidedly good thing that there now exists a film about white people participating in real struggles for liberation alongside those who’ve been trying to get free? This isn’t Sandra Bullock in The Blind Side – the ultimate white savior movie – saving a Black kid from the projects because she feels sorry for him. This is a film that tells the true story of a poor white guy who believed in and spent the better half of his life fighting against all odds for true collective liberation – economic and racial – not just because he was morally compelled to by his “wokeness,” but because he wanted an end to his own exploitation too.

But to Newkirk, being “the wokest white dude” seems to be a wrong, even offensive thing to be. Implicit in this “accusation” is the belief that the only real role for white people in ending white-supremacy is that of being guilt-ridden, Tim Wise-quoting, tokenizing cheerleaders and we wholeheartedly disagree. We need more Newton Knights, not fewer.

Likewise, Newkirk’s aesthetic criticism flows directly from his political positions. In turning his attention to the director’s technical choices he declares that, “The film loses its narrative way and becomes a mashup of vignettes around this point, but the vignettes each recall some real-world commentary on race and current events.” We see it differently. Rather than “losing its way,” the film draws out two important lessons. The first is that racism is deep-rooted, systemic, and long-lasting. The other is that interracial unity is key in the fight to overcoming it. Newkirk essentially argues this on accident, but misses the conclusion because of his faulty premise. And it happens more than once.

Newkirk asserts that despite the fact that voter-intimidation, lynchings, and massacres are perpetrated against black people: “...it’s Knight who is always front and center, issuing platitudes about economics, poor folks, and rightness in McConaughey’s textbook drawl. There’s even a scene where Knight leads a group of grown black men to the ballot box because they are too afraid to do so otherwise.”

Now that would be an odd decision for a director who sees white people as obstacles in the fight for black liberation, but Ross is making a different case. In the face of white terrorism against Black communities, unwavering solidarity from those who are privileged enough to turn a blind eye is a necessity. This is just as true today as it was during the Freedom Rides and indeed as it was in Knight’s time.

To be fair, Newkirk’s criticism is mostly that Knight is given an outsized role, and not that he is given any role. But even here he is missing the point. At a time when scores of white people can all too comfortably assert that “All Lives Matter,” a film profiling a white, radical, anti-racist is not about making white people feel good about themselves, but rather about actually challenging them to step up their game. Progressive audiences should continue to challenge Hollywood's still too lily-white status quo, and demand to see films about Rachel or Moses, played by Mahershala Ali, but that shouldn’t necessarily mean that films about white people in struggle and solidarity with people of color (i.e. comrades) should stop being produced.

In our estimation, the whole point of talking about race and racism is to challenge people, particularly whites, to move beyond their learned bigotry and eventually win them to building strong and sustainable movements. Because what we need are movements rooted in fighting everyday racism with the intended goal of eventually destroying white-supremacy for good. This is not only a matter of principle, but also because it is in the self-interest of whites to help people of color as they liberate themselves.

Long live the Free State

For those of us that can broadly agree that there already exists a basis for an intersectional, class-based politics that can unite people in common struggle, there are a number of reasons to celebrate Free State of Jones.

There is now a major motion picture about the American Civil War, told from the perspective of people who rebelled against the Confederacy. It is critical, at a time when the elusive “white working class” is so often theoretically set apart from and opposed to people of color, that the myth of the white monolith is cracked and shattered. The story of the Knight Company serves as more than just a moving history lesson. It is part and parcel to our vision for emancipation. Like the Communists organizing underground to “Finish the Tasks of Reconstruction,” in the Jim Crow south, the militants of the real Free State of Jones are part of a proud legacy which today's radicals should seek to emulate.

Moviegoers are being exposed to a kind of hero, rare in Hollywood, who is compelled by more than bad circumstances or good intentions. Ross’ Newton Knight is actually driven by an articulated vision of a new society. It matters that the story is told in a popular way, in theaters, to mass audience members who maybe haven’t yet read Foner and don’t yet have portraits of Malcolm X in their houses. In our opinion, at the present moment, the best art and the best politics will attempt to appeal to the existing mass consciousness while also attempting to raise it a bit higher.

We recognize that debates around identity politics will continue to take place for a long time to come and that we’re nowhere close to having the last word, but there are plenty of worthwhile lessons to draw from Free State of Jones. Lessons about collective struggle for material gains and solidarity that will go unlearned if we simply chuck it in the “white-savior” trash along with The Blind Side.

Is it a perfect film? No. Should it have been made? Absolutely.

And we’ll never know how many young people are challenged to take up a cause by films like this, but we dare say that the more this sort of narrative permeates popular culture, the easier our job as revolutionaries will be. With any luck, Free State of Jones is a sign that more of these films will be made.

* * *

Free State of Jones, directed by Gary Ross, starring Matthew McCoughnahey, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, and Mahershala Ali.

Crystal Stella Becerril is a Xicana activist and writer currently based in Portland. She is currently an editor at Red Wedge and has contributed to Jacobin, Socialist Worker, In These Times, and Warscapes. She writes about race, feminism, education, and the intersection of politics and culture.

Jason Netek is a socialist, activist, and organizer from Texas. He worked for Today's Zaman newspaper in Istanbul before its seizure by the Turkish government. He once joined a solidarity brigade to Venezuela to visit occupied factories during an election year and also drove around Athens on a scooter throwing "vote OXI" fliers into crowds. His writing has appeared in Links: Journal of International Socialist Renewal, Green Left Weekly, Socialist Worker, the International Socialist Review, Venezuelanalysis, the Indypendent, and also his silly travel blog