“Snobs reproached me for giving up ‘pure art.’ Dogmatists said menacingly that I was a ‘Nihilist.’ But I didn’t give a damn about any of them. What mattered to me were all those young eyes, turned toward me, waiting expectedly. I saw that they needed my poetry, and that, by speaking of what was wrong with our society, I was strengthening, not destroying, their faith in our way of life.” – Yevgeny Yevtushenko, A Precocious Autobiography, 1963.

Today’s generation is raised under a dark shadow of intellectual pessimism. To be sure, it is a pessimism entirely justified by the entire experience of the 20th century as well as the 21st century up to now. But the function of a revolutionary in this is to fight, to rekindle the socialist imaginary, not because the outlook is good but because there is no other option. Our choices are to resist or be consumed. Revolt can be a joyous festival, a celebration of a future yet to be birthed. This is what Vladimir Mayakovsky[i] meant when he said, well before he shot himself, that “joy must be ripped from the days yet to come.”

The popular avant-garde exists to exploit the contradictions within the popular culture, to thrust upon society a discourse about itself, in its own terms; to turn society’s narrative in on itself; to point toward the future by reference to the past and by liberation of the latent tendencies of the present. In casting about for exemplars of this convention, we are hard pressed to find anyone worthier of than the recently-departed Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Yevtushenko, who could by all rights be called Mayakovsky’s heir – and certainly desired to be – maintained that “artificial optimism doesn’t make people advance, it makes them mark time.”

Yevtushenko was never content to merely mark time. He said that he was indebted to the future. His was to restore the people’s faith in life by acknowledging the clashes between the good and the bad, even in a society which no longer acknowledged anything but the good and the even better. He would do so by reaching out into the future and grasping hold of what had brought Soviet society into existence in the first place, a gaze into a future worthy of supplanting the present.

At the height of his popularity, Yevtushenko’s readings would attract enormous crowds, entirely unthinkable in the West outside of the context of a major sporting event or concert. Poetry had become an article of liberation; a mechanism to facilitate the re-emergence of popular participation in society in the post-Stalin USSR. Yevtushenko, who yearned for the revival of the spirit of 1917 – who personified the aspirations of de-Stalinization and Perestroika – died in April of this year, just 6 months shy of the 100th anniversary of the revolution.

The revolution isn’t dead...

Yevgeny Yevtushenko was born in Siberia in 1933. His Ukrainian family had lived there ever since his great grandfather was deported for burning down his landlord’s home. Raised primarily by his mother, he attributed his “hard, proud faith in the revolution”[ii] to his upbringing. Revolution was the religion of the family. Young Yevgeny’s bedtime lullabies were the melancholic songs of the Russian Civil War, sung to him by his grandfather; an organizer of the peasant movement, an officer in the Red Army, and ultimately a victim of Stalin’s purges.

Despite the devastating loss of irreplaceable human material to the Great Terror of the late 1930’s, and the Second World War immediately after; despite the disappearance of his grandfather – a hero of Bolshevism’s triumph – into the Gulag, Yevtushenko had a faith in the revolution, not as an event but as a process, a history still unfolding.

In years immediately following the Soviet victory over Hitler’s Germany, Russian poets had “turned dull again” after years of turning out fine work designed to spurn the struggle onward. Poets wrote about construction, about production. “If the machines could read,” Yevtushenko quipped, “they might find such poetry interesting.”[iii] Throughout the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, the young Yevtushenko wrote poetry, and had it published wherever he could, but tried to keep his poems above his thoughts of social struggle and civic engagement. This would remain his thinking right up until the death of Stalin in 1953.

On a day that he later described as a turning point in his life, Yevtushenko went to see the departed Man of Steel, lying in state. He watched the police helpless as terrified crowds crushed people beneath their feet, trying to get a glimpse of the corpse of a man that had been like a god. He said that on that day, he realized that there was no one left to do the people’s thinking for them. Finally, his sense of social responsibility and his talent for the written word would converge. “No, Russia is not a Babylon in ruins![iv]” he declared, the only ruins were those of the “gilded paper-mache city of lies, built upon gullibility and blind obedience.[v]”

Ever since the first All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934[vi], the culture of the largest nation on earth had been stultifying, dogmatic, censored, and orchestrated. It had been the opposite of revolutionary. It had been official. With Stalin and Beria[vii] gone, the era of the so-called “Khrushchev Thaw” had begun and it appeared that Soviet society was opening up. Yevtushenko would take de-Stalinization at face value, in defiance of its limitations, and seized upon the opening. He saw in it a “spiritual revolution” in which the constructive-utopian essence of Bolshevism could be reborn in the hearts of the Soviet people.

The official literary doctrine of “Socialist Realism”[viii] was still firmly entrenched; long gone was the radically experimental era of Mayakovsky, Lissitzky, and Lunacharsky. Nevertheless, Yevtushenko had found ample room to both exhibit the official Soviet Patriotism and urge the youth to transcend it.

He warned of the continued grip that the “The Dead Hand of The Past” still had on society, that here and there “someone still glares in the Stalin manner.”[ix] He extolled the heroism and sacrifice of the generation that endured the Great Patriotic War, in the face of both the S.S. and Wehrmacht, and of the N.KV.D. and administrators of Kolyma and Vorkuta. In “Babiy Yarr,” later set to music by Shostakovich, he attacked the persistence of antisemitism in the former land of the Tsars.

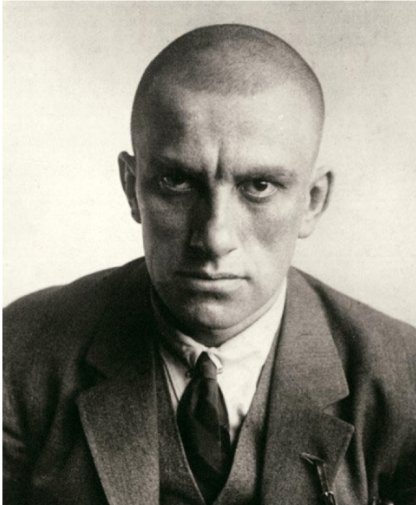

Vladimir Mayakovsky (photo by A. Rodchenko).

Yevtushenko believed that the Stalin era, while casting a heavy shadow over the present, was not a negation the possibility of a communist future:

And although we

did not know how to dodge and steal,

neither informers on the citizens,

nor Beria

got us to lose faith in Soviet rule,

to lose faith in the Commune.

And the Commune,

not striking bargains with anyone,

we shall earn

with our hands

and teeth.[x]

Yevtushenko was not a dissident in the mold of Solzhenitsyn. His faith was not in the West nor was it in the state. It was in the ideals of 1917 and in the Soviet people’s ability to resurrect them. While the “Thaw” only lasted until 1962, Yevtushenko, who had been expelled from the Komsomol[xi] for his poetry in 1956, never ceased his own personal campaign, making full use of his semi-official platform. He objected to the term “thaw” and instead referred to “spring;” the death of a harsh winter which plagued the new season with the occasional late frost, even as it was decidedly beaten back. If de-Stalinization was designed to legitimize the post-Stalin leadership, Yevtushenko would use the opportunity to denounce the Heirs of Stalin among them; the “former henchmen” who resented the “era of emptied prison camps.”[xii]

...the revolution is sick, and we must help it.

“I read the poem that ‘K’ had said was written ‘for our enemies.’ But the young people who heard it took it not as an attack upon our country, but as a weapon of struggle against those holding her back...and fifteen hundred hands, raised in applause, voted for that struggle.”[xiii]

Yevtushenko would later hail this moment in 1955 – a small bookshop reading that grew so large it had to be brought into the street – as the “return of public poetry,” a tradition of Mayakovsky in the post-revolutionary era of socialist construction of the 1920’s. Poetry had mobility. He began to read in factories and research facilities, in colleges and offices, calling for “recruits” to the crusade of restoration, reappraisal, and re-forging of a socialist culture utterly obliterated by fear and dogmatism.

In his younger days, he merely wanted to “speak the truth” for its own sake. By now he felt he understood the role that poetry could play in the struggle for purification, not just one’s own soul, but the soul of an entire people. From this moment onward, he would write and perform his works with all the revolutionary zeal he could muster, as though he were involved in the same socialist construction as was his hero, Mayakovsky. In 1961, Yevtushenko performed 250 public readings. By 1963, he could draw a crowd of fourteen thousand. At the height of his influence, he would read before hundreds of thousands at a time. And by all accounts, he performed with the passion of a person participating in the making of history.

Yevtushenko hated the “empty verses and countless quotations”[xiv] of the “obedient servants”[xv] doling out the official ideology. He had decided, years before Stalin died, that his was a struggle against those who “preach Communism in theory and discredit it in practice.” They spoke the same language, but for Yevtushenko, the words had different meanings.

Comrades,

we must give back to words

their original sound.[xvi]

His hijacking of the official discourse got him expelled not just from the Komsomol, but from his university and from the Union of Soviet Writers. Between 1963-65, Yevtushenko was not allowed to travel outside of the USSR and he lost many of the privileges normally associated with an artist of his stature and influence. He was too honest; he made too much trouble.

Boris Kagarlitsky once remarked that Yevtushenko’s evolution illustrated the Soviet crisis of ideology[xvii], that with the rollback of de-Stalinization under Brezhnev, the civic poet of the Thaw had lost himself in the 60’s[xviii] and never managed to find a new self in the 70’s. By the late 1960’s, the reformers of the “liberal decade” had mostly retreated into samizdat[xix] or into some rapprochement with the government. Yevtushenko neither abandoned his Soviet Patriotism, but nor did he allow himself to become an ally of the Heirs of Stalin. Rather he continued to try to revive the spirit of 1917 in defiance of a bureaucracy that saw no need for it. He joined Sartre and Shostakovitch in campaigning for imprisoned Soviet poet Joseph Brodsky.[xx] He publicly supported the Prague Spring and “Socialism With A Human Face,” and he spoke out against the war in Afghanistan. He was deemed “anti-Soviet” by the KGB’s Yuri Andropov, future Soviet premiere and personification of the Soviet gerontocracy’s stale bureaucratism.

At the same time, genuinely anti-Soviet writers in the West criticized his persistent identification with Communism and the Soviet government, or at least what he imagined the Soviet government could yet become. In 1973, Robert Conquest penned an article for the New York Times lamenting “The Sad Case of Yevgeny Yevtushenko”; someone he had once seen as the “Galahad of Liberalism,” with a once-promising career but who had degenerated into an apparatchik; which is to say, he continued to profess a belief in Soviet renewal instead of moving further and further from Communism. Even under Brezhnev’s Stalinism-lite, Yevtushenko continued to proclaim the revolutionary possibilities of tomorrow:

Timid youth,

I am preaching to you:

Charge forward,

headlong into the epoch,

without wasting

the wind of history...[xxi]

While never showing any public interest in Marxist theory, his grasp was firm enough to know that “no ideology in its final shape can be Marxist because genuine Marxism is forever molding itself.” He never joined the Communist Party but he always identified himself as a communist. He visited Cuba and maintained contacts in Communist parties outside his own country. He always spoke of the heroism of the Vietnamese people’s struggle. In addition to his two visits to Cuba, he lent his pen to the script of Kalatazov’s 1964 celebration of the revolution, I Am Cuba.

Kalatazov's I Am Cuba (1964).

Yevtushnko always considered the borders between nations to be an obstacle in his life; something for which he was criticized harshly by detractors at home. When he obtained a permanent passport, he traveled extensively, which was seen as a sign of his being an apparatchik to his critics in the West. He counted Pablo Neruda and Salvador Allende among his friends. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, he met with Che Guevara every day for a week. But he also moved comfortably in artistic and literary circles of all kinds. His was an extraordinarily idealistic faith in the power of exchange. He traveled the world, attempting to embrace the whole of humanity, advocating rapprochement and free travel between East and West. His internationalist, fraternal exchanges, like his public readings at home and abroad, where rooted in the same fundamental belief in the widening of horizons.

Even the tense international circumstances of the Cold War could, he hoped, be utilized to make the process of a new socialist reconstruction irreversible. “Just like our reactionaries, your reactionaries need the image of a bogeyman,” he said of the Reagan Era United States, “You love our liberals…but you don’t like your own liberals.”[xxii]

Border Guard of the Country’s Conscience

“We have made many mistakes. But we were the first to attempt to carry out the ideas of socialism, and perhaps our mistakes were made in order that they should not be repeated by those countries that follow in our footsteps.”[xxiii]

In the 1980’s, having endured the Years of Stagnation, he enthusiastically endorsed Gorbachev's program of Perestroika as the “testament of the real fathers of the revolution,”[xxiv] and of Glasnost; their “preserved voice.” Four years before the dissolution of the USSR, his poem, Bukharin’s Widow declared, “O Anna Mikhailovna, you did not preserve the testament in vain, for one day we will say as a nation: if we are born of Lenin, of October, then we are of Bukharin too.[xxv]”

In 1989, Yevtushenko was elected to the Congress of People’s Deputies, a platform from which he promoted Gorbachev and Perestroika. His fear of the heirs of Stalin led him to support Boris Yeltsin’s efforts in Moscow against the August Coup of “hardliners” in 1991. This may seem to us as an odd position for a supporter of the Soviet government to take, going back to the era of empty verses and countless quotations. Perhaps it was mere naivete or a sense of lesser-evilism that allowed him to back Yeltsin in an attempt to “save Perestroika.” Perhaps Kagarlitsky was right, he was lost, that his tactics had degenerated into politicking.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, its people suffering immensely, Yevtushenko finally began to temper his optimism. He soon denounced Yelstin and his war in Chechnya. When given the medal of a Defender of Free Russia, awarded to those who opposed the August Coup, Yevtushenko announced, “These difficult times are not worthy of our hopes.”

In 1992, Yevtushenko moved to Oklahoma, the land of Woody Guthrie, to teach poetry at the University of Tulsa. While his role as a purveyor of a revitalized communism did not last beyond the death of the Soviet Union, he maintained for the rest of his life that both “marketism” and Stalinism were in ruins and he lamented this era in which “ideals have been shattered and expedience reigns.” But he never seemed to lose his hope for humanity.

At Nelson Mandela’s death in 2013, Yevtushenko referred to the hero of South Africa’s liberation struggle as “one of the best and most righteous people on the planet,”[xxvi] not only for his dedication to the cause, but because he never allowed himself to hold a grudge, to stay in the past, but instead looked to the future. Yevtushenko compared the racial solidarity of the anti-apartheid movement to the ability of the Soviet and German people to cooperate even after the war which cost the lives of 20 million of his countrymen. “You should not rush to call anyone lost,” he once remarked of a student of his in Oklahoma. She had been under the impression that the Soviets and the Nazis were on the same side against the United States. He patiently, gently told her “the whole story, everything.” She became one of his best students.

If he had gotten his way, Yevtushenko would have witnessed the triumph of a socialism which was international in scope, free in spirit, and unafraid of new ideas, no matter from where they came. He lived for a future to which anyone with a shred of hope is indebted, for all that we borrowed from it. Throughout the shifting terrain of the decades, through an official discourse which was sometimes friendly and sometimes hostile, to dare us all to dream of a world which might yet be. He never lost his faith in the people, but he never fell victim to comforting illusions either.

Remarking on the cultural environment of the early 1950’s, when Stalin was still alive, Yevtushenko wrote: “In the long run, that insistent, rosy-cheeked false optimism – that flexing of the biceps for everyone to see – only leads to discouragement and decay. Whereas a clean honest, unsentimental melancholy, for all its air of helplessness, urges us forward, creating with its fragile hands the greatest treasures of mankind.”[xxvii]

Perhaps that’s just what he had in mind in 1995 when he penned the following lines:

I didn’t take the Tsars’ Winter Palace.

I didn’t storm Hitler’s Reichstag.

I am not what you call a “Commie.”

But I caress the Red Flag

and cry.[xxviii]

Endnotes

[i] Vladimir Mayakovsky, 1893-1930: Renowned Soviet poet of the revolutionary era. His funeral was the third largest in Soviet history, behind Lenin and Stalin.

[ii] George Reavey, The Poetry of Yevgeny Yevtushenko, p XVII

[iii] A precocious Autobiography, p76.

[iv] A Precocious Autobiography, p92.

[v] Ibid

[vi] https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/lit_crit/sovietwritercongress/index.htm

[vii] Lavrenty Beria, 1899-1953: Stalin’s third arch-henchman, head of the NKVD, executed for overseeing a purge of the Red Army – classified as an act of terrorism – which began in 1940 and continued, through the German invasion, into 1942.

[viii] https://www.britannica.com/art/Socialist-Realism

[ix] “Dead Hand of the Past,” 1965.

[x] “Members of the Commune Shall Never Be Slaves,” Bratsk Station, 1966.

[xi] The Young Communist League

[xii] https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-heirs-of-stalin/

[xiii] A Precocious Autobiography, p??

[xiv] “Station Zima,” 1956

[xv] “You Can Consider Me a Communist,” 1962

[xvi] “Enthusiasts Highway,” 1956.

[xvii] Boris Kagarlitsky, The Thinking Reed, p. 200

[xviii] Ibid, p. 203

[xix] Self-published, underground literature.

[xx] Brodsky (1940-1996) was imprisoned on charges of “social parasitism” and “failing to work for the good of the Motherland by holding only various odd-jobs and writing poetry that made little contribution to society.” His sentence of 5 years hard labor was commuted to 18 months after a public campaign.

[xxi] “Tomorrow’s Wind,” 1977.

[xxii] https://www.thenation.com/article/on-the-poet-yevgeny-yevtushenko/

[xxiii] A Precocious Autobiography, p. 123

[xxiv] http://www.nytimes.com/1988/01/19/world/new-yevtushenko-poem-praises-stalin-victim.html?pagewanted=all&mcubz=3

[xxv] Ibid

[xxvi] https://www.rbth.com/arts/2015/02/23/yevgeny_yevtushenko_you_shouldnt_rush_to_call_people_lost_43685.html

[xxvii] A Precocious Autobiography, p 72.

[xxviii] “Goodbye, Our Red Flag,” 1995.

This piece appears in our fourth issue, “Echoes of 1917.”

Red Wedge relies on your support. If you like what you read above, consider becoming a subscriber, or donating a monthly sum through Patreon.

Jason Netek is a longtime socialist, activist and nuisance from Texas. After a period of wandering the earth, doing as little work as possible, he moved to Hollywood to contribute to the cultural emasculation of Christian civilization. He is a member of Democratic Socialists of America’s newly formed Refoundation Caucus and the Red Wedge editorial collective. Jason is now on Twitter: @dialectronixxx