The leveling, or weak-strong, image

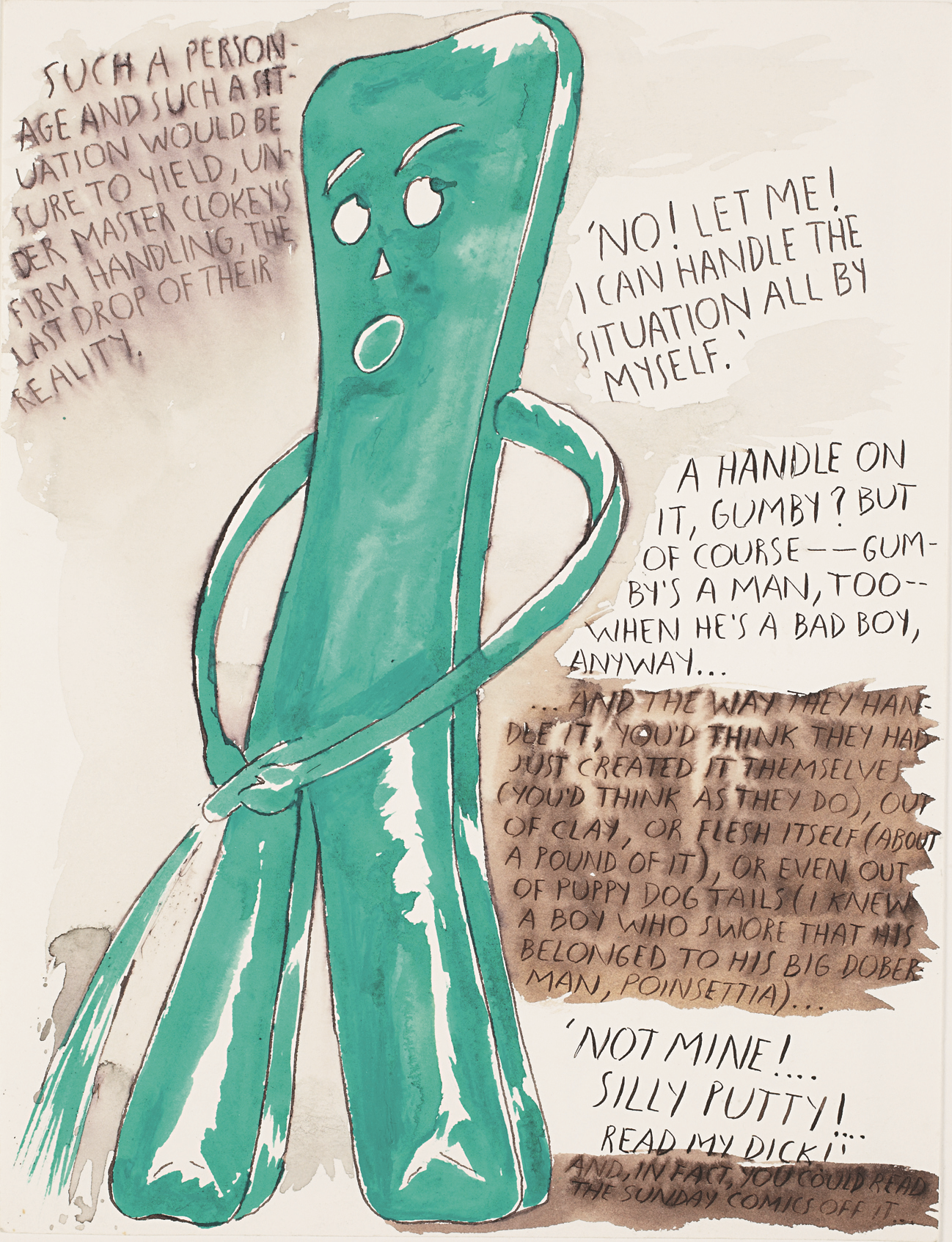

The strong images of the dominant culture offer no way out for the proletarian subject. Likewise the weak images of much of the academic avant-garde offer very little. The solution, for the class-conscious artist, is to connect weakened art and a weakened working-class to universal and totalizing aspirations. In my opinion the strong-weak image is the mode of the popular avant-garde. And historically it has come from outside the art world as often as within it – and sometimes both, in the work of the Wild-Style graffiti innovators of the 1970s and the punk rock DIY posters and zines of the 1970s and 1980s. Raymond Pettibon, highly influenced by William Blake and Goya, [i] was central to the early punk visual aesthetic, producing art for his brother’s band, Black Flag. The tension between “weak” and “strong” inherent to his work was summarized by Pettibon himself when he argued, “I am really asking is for you to look at Gumby with the same kind of respect that you would if it was some historical figure or Greek statue.” [ii]

As Benjamin Buchloh observes, Pettibon is continuing and arguing with the work of Andy Warhol – too often dismissed by the left and too often emptied of contradiction and depth by his would-be inheritors. [iii] Warhol’s leveling worked in multiple ways: bringing the popular and “kitsch” into the art space and then reintroducing the mark of the hand (however mitigated through mechanical reproduction) in the flaws of his screen prints. But Warhol – the son of a working-class Pittsburgh family – keeps doubling down. Like Pettibon, Warhol invoked Goya in his own disaster series (in work largely ignored in the U.S. but celebrated in Europe). [iv] This is not popular content per se but popular concerns: repressed sexuality and violence (the Most Wanted Men series banned at the 1964 World’s Fair), and mortality, both individual and social (Marilyn, Race Riot, 129 Die in Jet). [v] Pettibon and Warhol do not produce weak images but strong-weak images – incorporating the tensions of this world and the next – in the case of Pettibon in the degeneration of the “American Dream” that characterized early punk. [vi] This mirrors the actions of the first generation of great graffiti writers – claiming the urban space as their own, albeit symbolically. [vii] Such leveling does not eschew unfolding dystopias (as with the false equality of “atemporal painting”) but introduces social and existential contradictions – free expression vs. the bureaucratic city, disdain for failing official moralities, the death masks of celebrity, images of electric chairs reproduced as artistic fetishes.

As Jamie Reid describes the early punk art milieu:

The growth of the independent DIY [punk] scene in the late 1970s… resulted in graphic design for record sleeves, posters, flyers, and fanzines that could be targeted to specific, often small-scale, markets. Many of these could be regarded as strongly noncommercial in terms of the mainstream record industry, or in the handmade, labor-intensive nature of the packaging itself. Their designs often involve strategies that, although based on limited budgets, were inventive and sophisticated – incorporating alternative production processes, the adaptation of available, lo-tech materials, and simple, often handcrafted, printing techniques. [viii]

Early punk‘s visual artists recall Arte Povera’s use of “poor” materials – in particular the political “igloos” of Mario Merz and the interventions of Michelangelo Pistoletto (Venus of the Rags and the Vietnam mirror paintings). Just as punk was born of deindustrialization – and a rolling back of development among industrial workers in the U.S. (and elsewhere) – Arte Povera was born of Italy’s post war industrial boom (and antagonism toward U.S. imperialism and art-world arrogance). Arte Povera responded to American-style consumerism with a left-wing cultural romanticism. In 1967 the art critic Germano Celant published his essay “Arte Povera: Notes for a Guerilla War” comparing the group’s aesthetic strategies with the national liberation wars raging in Latin America, Africa and Asia. [ix] As Nicholas Cullinan writes:

Celant’s characterization of Arte Povera reflects Italy’s struggle to reconcile and adapt to its transition from a relatively impoverished and predominantly agrarian country ravaged by World War II to the rapidly industrializing nation propelled by the Marshall Plan-backed miracolo italiano, or economic miracle, in the late 1950s and early ‘60s. Together with American aid, the growth of companies like the Turin-based automobile company Fiat… contributed to Italy’s burgeoning foreign trade. Yet this ‘miracle’ caused Italy a great deal of social tension and upheaval. A case in point was the dislocation engendered through the geographical and economic schism of mass migration from the poor South to the rich North. [x]

Uneven and combined development (UCD) provokes, by necessity, a cultural dislocation – with all its gothic and futurist notes, breaking both to the left and the right. There is no transcending such dislocations with weak images. The beauty and pathos comes from the struggle itself – in the Bronx, in Los Angeles, in the Factory (both Andy’s and Fiat’s), in Pittsburgh, in Turin.

Differentiated totality, or the carnivalesque

The collective working-class, the majority of the population defined in terms of a relationship to economic production, is the key to the transformation of society. But the working-class is not homogenous. It is defined by its thousands of differences: race, gender, sexuality, nationality, psychologies, cultures, biographies, etc. It cannot come together by subsuming those differences. But the enemy – neoliberal capitalist culture – depends on the isolation and separation of all these elements. A left-wing cultural opposition unites these in a differentiated totality. It comes together without sacrificing the subjectivities of its constituent parts. It avoids vulgar Marxism as well as the fatalism of postmodernism and middle-class strands of anarchism. It echoes Mikhail Bakhtin’s ideas of the carnivalesque, taken from Rabelais, but it is fused with the avenging crowds of the Zola novel. Differentiated totality is the enemy of both rhizome and (class) hierarchy. The crowd has returned but not yet cohered: in Spain, in Greece, in Occupy, in Ferguson. In order to avoid the fate of the Egyptian heroes it must learn to express a new totality.

"Pantagruel," after Gustav Dore

Rabelais borrowed his ideas of the carnivalesque directly from the peasants of late medieval France, collecting wisdom “from the popular elemental forces” of “idioms, sayings, proverbs, school farces, from the mouth of fools and clowns” [xi] and in so doing was “the most democratic among” the “initiators of new literatures” [xii] – “at home within the thousand-year-old development of popular culture.” [xiii] Key to the presentation of a chaotic totality – a threatening diversity – in Rabelais is the carnival. The medieval carnival institutionalized, over several months each year in the late middle ages, a reversal of fortune – the weak would be strong (or the strong would be ridiculed), the powerful would serve, etc. – in events such as “the feast of fools” or the “feast of the ass.” [xiv] Orchestrated spectacles [xv] aimed to, albeit in a confused manner, democratize the medieval commons through:

- Ritual spectacles: carnival pageants, comic shows of the marketplace.

- Comic verbal compositions: parodies both oral and written, in Latin and the vernacular.

- Various genres of billingsgate: curses, oaths, popular blazons. [xvi]

Clowns and fools – the descendants of the shamans – were at the center of these events. These carnivals were almost always held at “moments of crisis” in the calendar (solstices, etc.). “In the framework of class and feudal political structure this specific character could be realized without distortion only in the carnival and in similar marketplace festivals,” Michael Holquist writes, “They were the second life of the people, who for a time entered the utopian realm of community, freedom, equality, and abundance.” [xvii]

Courbet, Rivera and Eisenstein

Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans (1850)

This “temporary liberation” from the “established order” [xviii] was progressively abolished with the rise of capitalism and the industrial revolution – but democratic aspirations found new paths. Gustave Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans famously translated his anarchist politics [xix] into the Salon of 1850-1851. [xx] Compared to academic painters Courbet’s painting was described as having an “anti-composition” – in that no figure is given primacy over any other. [xxi] “Courbet’s democracy of vision, “Linda Nochlin writes, “his additive, egalitarian composition, were seen as the concomitants of a democratic social outlook.” [xxii] Produced as a series of separate portraits of his fellow citizens Courbet makes his hometown equal in the face of death. [xxiii] A similar aesthetic would permeate much of 20th century muralism—particularly its greatest practitioners, the Mexican muralists, also highly influenced by radical (Marxist) politics. Courbet and Diego Rivera alike foreshadowed the “all-over” aesthetic championed by Clement Greenberg in New York School abstraction. [xxiv]

Diego Rivera, Man at the Crossroads

Likewise, Sergei Eisenstein (Battleship Potemkin, Strike, October) translated the dialectical principle “quantity becomes quality” to his version of film montage. [xxv] Eisenstein saw montage, as opposed to the static mise en scène of early cinema – including the pioneering work of George Méliès – as explosive in character. [xxvi] “[Whereas] the [filmmaker] Pudovkin argued that the most effective scene is made through linkage – smoothly linking a series of selected details from the scene’s action,” Anna Chen writes, “Eisenstein insisted that film continuity should progress through collision – a series of shocks arising out of conflict between spliced shots: ’…the juxtaposition of two shots by splicing them together resembles no so much the simple sum of one shot plus another – as it does a creation.’” [xxvii]

Sergei Eisenstein's montage technique

This is a dynamic equality – not the false equality of the “rhizome” in which a series of “random” objects are presented like butterflies pinned to corkboard. Of course there is a weakness to much modernist “democratic” presentation in that it often lacks the bodily chaos of the medieval carnivalesque, and therefore the full diverse and anarchic quality of the working-class. The new “epic” cannot not merely combine archetypes. It must aim toward [xxviii] fusing a massively varied constellation of individual subjectivities and cultural identities – united objectively (if not subjectively) against the forces that oppress and exploit them.

Jackson Pollock, Lavender Mist

Endnotes

[i] Robert Enright, “What Remains To Be Said: An Interview with Raymond Pettibon,” Border Crossings Vol. 29 Issue 4 (December 2010), 20-35

[ii] Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, “Raymond Pettibon: After Laughter,” October 129 (Summer 2009), 13

[iii] Buchloh, 15

[iv] Marcel Krenz, “Art in Times of Disaster,” Art Review 53 (2002), 26

[v] Krenz

[vi] Buchloh, 15-16

[vii] See Jack Stewart, Graffiti Kings: New York City Mass Transit Art of the 1970s (Abrams, New York: Melcher Media, 2009)

[viii] Russ Bestley and Alex Ogg, The Art of Punk: The Illustrated History of Punk Rock Design (Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press, 2012), 8

[ix] Nicholas Cullinan, “From Vietnam to Fiat-nam: The Politics of Arte Povera,” October 124 (Spring 2008), 8-10

[x] Cullinan, 13

[xi] Michelet, cited in the introduction, Michael Holquist, to Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984), 2

[xii] Michael Holquist, Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984), 2

[xiii] Holquist, Bakhtin, 3

[xiv] Holquist, Bahktin, 5

[xv] Holquist, Bakktin, 7

[xvi] Holquist, Bakhtin, 5

[xvii] Holquist, Bakhtin, 9

[xviii] Holquist, Bakhtin, 11

[xix] Alan Antliff, Anarchy and Art: From the Paris Commune to the Fall of the Berlin Wall (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2007), 17-36. Courbet, a follower of Pierre Joseph Proudhon, played a major role in the Paris Commune of 1871, leading the destruction of the Vendome Column, a symbol of French aristocratic militarism. Courbet was imprisoned and later renounced his actions during the Commune, therefore escaping execution.

[xx] Linda Nochlin, Courbet (New York and London: Thames and Hudson: 2007), 19

[xxi] Nochlin, 20

[xxii] Nochlin, 24

[xxiii] Nochlin, 27

[xxiv] See Norman L. Kleeblatt, et al, Action/Abstraction (New York: Yale Press and the Jewish Museum, 2009)

[xxv] Anna Chen, “In Perspective: Sergei Eisenstein,” International Socialism 79 (Summer 1998), 109-111

[xxvi] Chen, 109-111

[xxvii] Chen, 111

[xxviii] Of course doing this fully is impossible – it is the political art equivalent of the sublime.

"Evicted Art Blog" is Red Wedge editor Adam Turl's investigation of potential strategies for contemporary anti-capitalist studio art.