“[T]he last will be first, and the first will be last.” (Matthew 20:16)

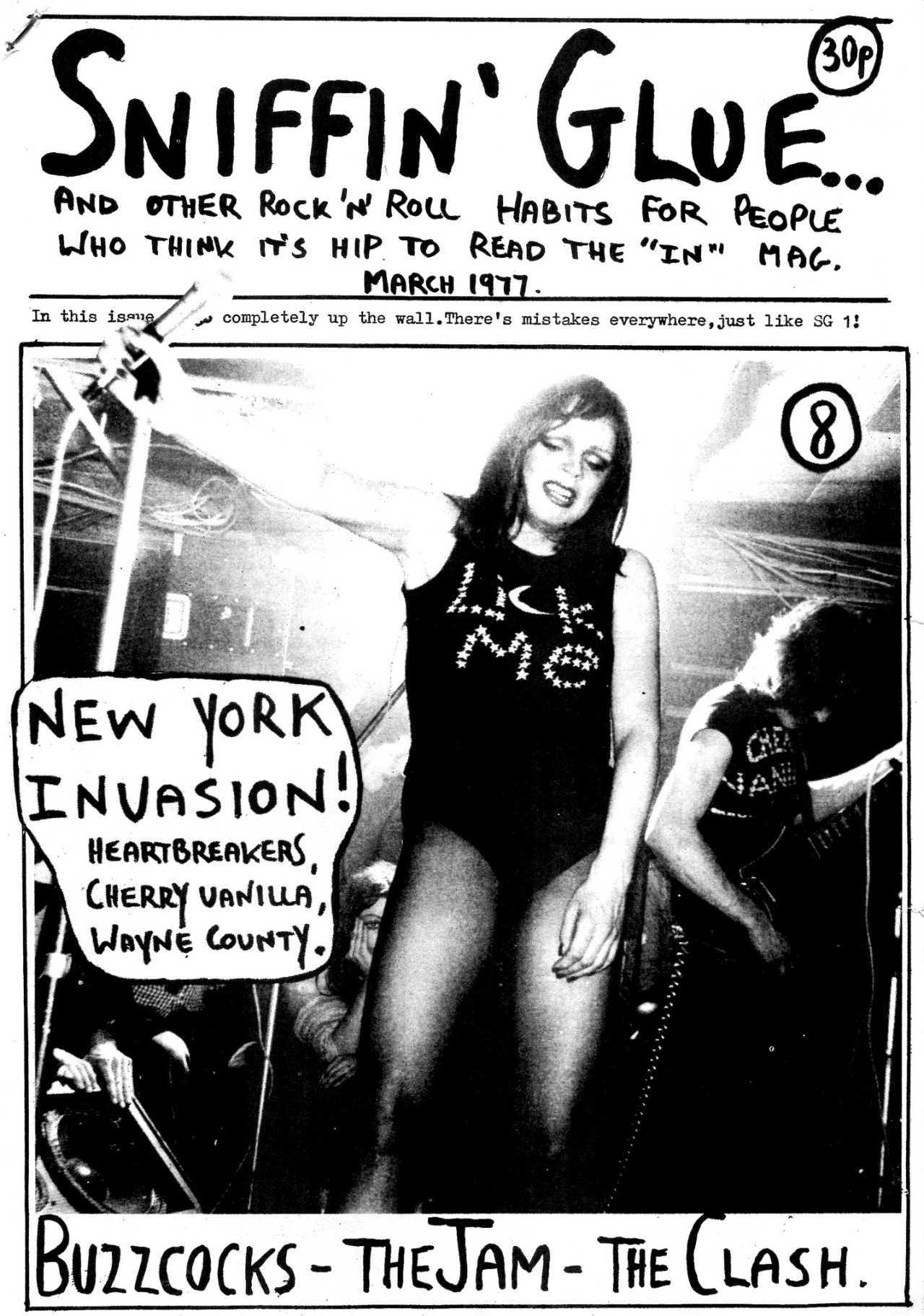

Sniffin' Glue, one of the first UK punk zines in the 1970s

“Leveler” was coined in the 17th century to describe those who tore down hedges in the Enclosure Act Riots.[1] It was later generalized. As long as the working-classes have sought political and economic leveling these aspirations have been expressed in art and culture – from the social gospel of Matthew to the gestures of punk and early Hip Hop. Aesthetic leveling can be used in ways that divert class anger toward the wrong targets or toward personalized solutions. But it also can express movement toward proletarian consciousness. And the socially promiscuous artist – coming from, and historically mixing with, all classes – is often predisposed toward leveling (as well as a political volatility that produces the aforementioned variations).[2]

Moreover, the leveling impulse is expressed in daily working-class genius. When the Parisian poor named their streets “Yank Penis” or “The Street Paved with Chitterling Sausages” it was an elevation of the “low” – tearing at aristocratic and bourgeois Paris’s idea of itself. In medieval Europe billingsgate was institutionalized in the carnival and festival. Rabelais’s carnivalesque presented a chaotic totality—a (potentially) threatening diversity. The carnival institutionalized a performative reversal of fortune—the weak would be strong (or the strong would be ridiculed), the powerful would serve, etc. This institutionalization, of course, negated any real threat but its aesthetic leveling, “comic verbal compositions” and other “genres of billingsgate: curses, oaths,” prefigured gestures to come. [3] When the American Revolution unfolded – in its actually revolutionary northeastern center – the mob was born – short for mobile. The term was coined to describe the throngs of laborers and small farmers that enforced revolutionary justice, symbolically and in actuality. They gathered at liberty trees and poles, sometimes decorated with the symbols of colonial resistance, and democratically planned their “mob justice.” The American mobile produced groups that tarred and feathered English officials. But it also produced mobs that lynched slaves and free Black working men.

"Raising the Liberty Pole 1776," painted by F.A. Chapman ; engraved by John C. McRae, 1875

In the absence of an objectively “socialist” path aesthetic riots can be dissolved in bourgeois tropes or directed into something worse. As Walter Benjamin’s famously argued: “The masses have a right to change property relations; Fascism seeks to give them an expression while preserving property. The logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life.” [4]

The “introduction of aesthetics into political life” and Benjamin’s Marxist counter, “politicizing art,” can produce similar-yet-antagonistic forms; in part because crises can create a “shared spiritual disposition” [5] (to borrow from Enzo Traverso). [6] This is not horseshoe theory. It is to say that a sense of social disintegration accompanying crisis infects everyone. Different aesthetic levelings can mirror each other responding to the alienation and grievances of the masses. In the case of the recent U.S. presidential election the “weak socialism” of Bernie Sanders and “weak fascism” of Donald Trump were born of the same crisis (although the voting base of each was largely divergent). Each “represented” political mobs that mortified the neoliberal center. But where one represented a nascent coalescence of class consciousness the other represented its historic antithesis.

There can be a symmetrical but antagonistic relationship between the aesthetic leveling of fascist vs. “socialistic” artistic gestures: “Jazz” in Brechtian theater vs. the assertion of German volkskultur; Rock Against Communism (RAC) [7] vs. anti-fascist punk/Rock Against Racism (RAR); the incorporation of popular forms in “high art” from both democratic and reactionary impulses (Expressionism, Constructivism, Surrealism, Dada, Pop, Arte Povera); etc. All these things positioned themselves against established practices or “elites.”

RAC vs. RAR: Rock Against Communism concert, 1978 Rock Against Racism poster. RAC concerts were largely failures.

In-between is a seemingly apolitical gesture. This is the aesthetic leveling of Caddyshacks and Rodney Dangerfields. The apparent enemy is not the bourgeois per se but bourgeois culture. While fascism presents bourgeois culture as decadent, liberal leveling presents bourgeois culture as stultified and snobby. By virtue of its acculturation (with the pre-capitalist ruling-class and “old money”) it has ceased to be “genuinely bourgeois.” Liberal (or neoliberal depending) leveling counters with Horatio Alger myths – celebrating those who successfully crash the party.

Aesthetic leveling is part and parcel of capitalist culture. Its gestures valorize the everyday life experiences of the masses – sometimes borrowing from “high” and “middlebrow” culture to give aura to popular impulses. At the same time, it tears down. It is the cultural echo of the riot, Emile Zola’s avenging crowds, the Boston mobiles, the protagonists in La Haine wrecking a haute Parisian art gallery. But it is also present in Nazi anti-art pogroms and Donald Trump’s conspicuous vulgarity. And a thousand inchoate things in-between.

The gallery scene in La Haine (1995) by Mathieu Kassovitz

What follows are preliminary notes on a cultural practice/tendency that is so widespread and common that it is not often described as such. The term “aesthetic leveling” is as likely to be used in the automotive industry as it is in left-wing artistic aspirations. But it is a gesture that is hard-wired into cultures under capitalism. Often, aesthetic leveling can incorporate multiple political trajectories as it is born of mixed consciousness, etc. Also because it comes from artists – historically tethered to a precarious petit-bourgeois and lumpen-proletarian milieu – a proven breeding ground for socialist, anarchist and fascist cadres – it produces chaotic results.

Artists + Bohemia

"As a famous letter from King Leopold to Queen Victoria warns, rather amusingly: ‘The dealings with artists...require a great prudence; they are acquainted with all classes of society, and for that very reason dangerous.’ ”[8]

Enzo Traverso notes that the Marxist approach to the subject of “bohemia” – the 19th century home of the artist – is contradictory. [9] He observes, for example, the contradiction between Leon Trotsky’s bohemian lifestyle and ideas on art in exile – “both before and after 1917” – and his positions in the Proletcult debate while he was in power. Similarly, Marx cut his teeth with and against “French Socialism.” Bohemia – drawing disaffected workers, declassed aristocrats, the lumpen, criminals, artists, intellectuals, prostitutes, and various “deviants” – was one one of the key intellectual/cultural centers that produced the socialist movement. In its Parisian heyday, from “the July Revolution of 1830 to the Paris Commune,” Traverso argues, “Bohemia was a privileged realm for conflating art and politics.” [10] This contradictory space/culture produced revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries, and thousands of intermediate states.

Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix (1830)

Traverso on Walter Benjamin on Baudelaire:

He remembers how the author of Les Fleurs du Mal took part in the events of February 1848, as he was marching down Paris streets shouting: “Down with General Aupick!” (his own stepfather), and then quotes another passage where this time the poet seems to spell out the nature of his rebellion:v I say ‘Long live the revolution!’ as I would say ‘Long live destruction! Long live penances! Long live chastisements! Long live death! I would be happy not only as a victim; it would not displease me to play the hangman as well – so as to feel the revolution from both sides! All of us have the republican spirit in our blood as we have syphilis in our bones. We have a democratic and syphilitic infection.”

According to Benjamin, this shows the typical signs of the ‘metaphysics of the provocateur’ that will culminate in the twentieth century with Sorel and Celine. [11]

“There is a path leading Bohemia to fascism,” [12] Traverso notes, as well as “socialism.” No one represented these opposing directions more than Georges Sorel. Reacting against the “Marxist” determinism of the Second International, Sorel focused on revolutionary mythology and violence. As such he became an intellectual forbearer for certain Marxists – particularly Maoists – as well as anarcho-syndicalists and proto-fascists (usually ex-Marxists and syndicalists) who believed violence could create a “national revolution” in so-called “proletarian nations” (such as Italy) or overthrow the decadence of stagnant bourgeois states (such as France). [13]

“Primordial rages” can be directed in multiple directions. Class is, in the final analysis, the most important factor. But the gravity of class operates in a social consciousness and sub-conscious full of horrors; an accumulated collective psychosis caused by thousands of years of class rule; beginning with our fall from grace, a grace traded for stored crops that would keep us alive when food was scarce. The real and artistic re-enactment of that rage is malleable. In his commentaries on Bertholt Brecht’s Reader for Those Who Lives in Cities Benjamin notes:

Brecht’s poem is revealing to the present-day reader. It shows with utmost clarity why National Socialism needs anti-Semitism. It needs it as a parody. The attitude toward the Jews that is artificially elicited by the rulers is precisely the one that would have been adopted naturally by the oppressed toward their rulers. Hitler wants the Jew to be treated as the great exploiter ought to have been treated. And because his actions against the Jews are not meant really seriously, because his treatment is a caricature of a genuine revolutionary process, sadism gets mixed in. Parody, which aims at exposing historical models to ridicule (expropriating the expropriators), cannot do without it. [14]

Benjamin, Trotsky, Sorel, Marx, Brecht and Baudelaire

It does not follow, as liberal and social democratic figures would argue, that all violence be rejected. The rage cannot be wished away with the platitudes of professors or party functionaries. In the end someone is going to “go down”; be pulled to the floor, kicking and screaming. In the end there are firing squads. This is virtually true in aesthetic leveling and in the literal outcome of politics. This partially vindicates Sorel (but not most of his ideological children) – on questions of myth and violence. “A historical materialist,” Benjamin argues, “recognizes the sign of a Messianic cessation of happening, or… a revolutionary fight for the oppressed past.” [15]

In Marx [the working-class] appears as the last enslaved class, as the avenger that completes the task of liberation in the name of generations of the downtrodden. This conviction, which had a brief resurgence in the Sparticist group, has always been objectionable to Social Democrats. Within three decades they managed virtually to erase the name of Blanqui, though it had been the rally sound that had reverberated through the preceding century. Social Democracy thought fit to assign to the working-class the role of the redeemer of future generations, in this way cutting the sinews of its greatest strength. This training made the working-class forget both its hatred and its spirit of sacrifice, for both are nourished by the image of enslaved ancestors rather than that of liberated grandchildren.[16]

It is incomplete to lift up (valorize). The enemy must also be torn down (riot). When André Breton spoke of the need for a myth opposed to the Nazi “myth of Odin,” this is part of what he was getting at; the “blood” of the working-class against fascism’s “blood and soil.” Either way there was going to be blood.

Courbet’s Democratic Gestures

Gustave Courbet, Romantic turned realist, epitomized 19th century bohemian socialism. He admired Fourier, called himself “a socialist, a democrat and a republican, ‘a supporter of the whole revolution,’” [17] during the Commune he served as a “delegate for the fine arts” – and it was in this position he famously “organized” the demolition of the Vendome column. [18] Courbet figured into Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s Du principe de l’art (1865) which critiqued the “metaphysical idealism” of the dominant Kantian and Hegelian ideas on art. [19] These ideas were the philosophical basis of “art for art’s sake” (although they were, in actuality, more complicated than that bourgeois reduction). Proudhon’s book was inspired, in part, by the repression of Courbet’s Return from the Conference at the 1863 Salon;[20] depicting “drunken clerics on their way home from a religious gathering” – stealing aesthetically from popular art forms (particularly mass produced woodblock prints made for the lower classes). [We are unable to find a high quality photograph of Courbet's Return from the Conference because in the early 20th century it was destroyed by an art patron who considered it anti-clerical and anti-Catholic-eds.]. This material “crudity” was interpreted as violating a Kantian or Hegelian “metaphysical ideal.” But Proudhon’s defense of Courbet demonstrated a false dichotomy between a valorized art and proletarian aspiration.

The Stone Breakers by Gustave Courbet (1850)

Proudhon, following Feuerbach, viewed metaphysical knowledge as an impossibility, and this informed his critique of artistic idealism, in which he attacked the idea that metaphysical ideas could spring, fully-formed from the artist. [21]

Proudhon defends the practice of painting as a separate valorizing category because a photograph could not “replicate the power of the artist to magnify the qualities of character residing in a subject or imbue an inanimate object with meaning.” [22] Struggling to defend the auric quality of the unique art object [23] in relationship to democratic impulses/gestures he reverts to a static democratic realism (unlike Courbet himself). Emile Zola argued that Proudhon’s analysis produced an “oppressive tautology” (the artist has value but the artist is nothing but a product of the world and subservient to its politics) familiar later in much socialist realism:

[Proudhon] poses this as his general thesis. I public, I humanity, I have the right to guide the artist and to require of him what pleases me; he is not to be himself, he must be me, he must think only as I do and work only for me. The artist himself is nothing, he is everything through humanity and for humanity. In a word, individual feeling, the free expression of a personality, are forbidden. [24]

Zola felt Courbet’s dedication to democracy and his own individual expression were bound together. It was in this manner Courbet’s paintings “lifted up” their subjects – “the man revealed through the work… has discovered how to create, alongside God’s world, a personal world.” [25] The reason this matters is because this is at the “source” of art itself; as the Marxist art critic Ernst Fischer noted in The Necessity of Art; the origin of art (or what became “art”) was in the projection of human imagination on the unknown during the biological, cultural and social-technological innovations of primitive communism. [26] Regardless, while Courbet’s friend attempted to theorize his paintings, Courbet was better than his friend’s theory. As Alan Antliff notes, Courbet had already caused a scandal at the 1851 state exhibition displaying two large paintings showing “rude subject matter” with “unfinished brushwork” [27] and “banal scenes from the life of the French peasantry in a style akin to popular woodblock prints”: Stonebreakers and Burial at Ornans. [28] This negated the surface of Courbet’s youthful Romanticism but was, conceptually and morally, its outgrowth.

Burial at Ornans by Gustave Courbet (1850-1851)

A Burial at Ornans translated Courbet’s anarchist/socialist politics into the Salon. [29] Compared to academic painters Courbet’s painting was described as having an “anti-composition” – in that no figure is given primacy over any other.[30] “Courbet’s democracy of vision, “Linda Nochlin writes, “his additive, egalitarian composition, were seen as the concomitants of a democratic social outlook.” [31] Produced as a series of separate portraits of his fellow citizens Courbet made his hometown equal in the face of death. [32] But this is not merely a “raising up” of Courbet’s home-town. It is also an accusation. Traverso argues:

Courbet painted A Burial at Ornans, the first realistic representation of people in modern art [sic], which was pertinently interpreted as the funeral of the revolution of 1848. In the 1860s, he devoted a cycle of canvases to hunting whose recurring theme is the death of hounded animals. The most famous of them, The Killed Hart (1867), shows a dying deer, lying on the ground and exhausted, being whipped by a hunter while dogs are impatient to dismember it. This painting is an extraordinarily and intense and uncanny allegory of the defeat of the revolution of 1848. [33]

The Killed Hart by Gustave Courbet (1867)

Leveling + Methods/Modes of Distribution + Production

Part of the false leveling of post-modernism was to pretend the boundaries between high and low culture had been obliterated. The problem with this pretense was that the institutions and economies of high and low culture persisted (as much as the social classes to which they were historically associated). There are still Salons. Their gatekeepers are no longer royal academics but (often) bourgeois academics, curators and corporate executives. The art museum, the symphony, the avant-garde theater, the record label, the movie studio, the television station; none of these things ceased to exist because professors prattled on about rhizomes. They evolved, and they did blur, but the much heralded democratization of culture never materialized. While the forces of production appeared to be leading in that direction, the relations of production remained intact. Indeed, the deteriorating balance of class forces insured a kind of regression (in terms of class) in the arts. Instead of democracy we got atomization.

When “left” art theorists like Nato Thompson argue that “[a]rt and life have in fact merged” [34] this is only true with the widest possible definition of art – if one counts advertising, all aspects of popular culture, social media, etc. Thompson claims he “defines culture simply”; and herein lies the problem. [35] Art, as a special category of human behavior, distinct from selling Coca-Cola, is less considered. Thompson’s utilitarianism turns him into a contemporary Proudhon.

Which is the "democratic image?" Michelangelo Pistoletto's Venus of the Rags (1967) and The Young Victoria (2009)

One does not have to believe in Kantian or Hegelian metaphysics to understand that the meaning of certain cultural products changes based on the nature of their production, distribution and consumption. These are contradictory. The mass product is far more “democratic” in its consumption and distribution than the rarefied art object; but its production is often more controlled and homogenized. The unique art object and experience is far less democratically distributed and consumed; but its production can be virtually anarchic.

The “white cube” art-space is, as Danica Radoshevich argues in “Zombie Gallery: The German Ideology and the White Cube” (Red Wedge) an expression of bourgeois thinking. The art object is removed from the social context and processes that produced it. At the same time, the art space valorizes the object for multiple – even opposing – reasons. Fetishes existed before the commodity fetish. And most of them are part of the historic trajectory of art. The isolation of the human made art object imbues those objects with power as a record of human performance. This is neither inherently reactionary or progressive. It depends on the actual content of those gestures and objects and how they are presented (although these will, like all cultural products within capitalism, be reified). The white cube, therefore, separates and valorizes. This raises a number of strategic questions about how radical artists can interact with said space; beyond merely denouncing it and moving on.

Secondly, images have their own dynamics. As Jacques Rancière notes in The Future of the Image, images have a peculiar alterity, they refer “to two different things”; the “likeness of an original” and “the operations that produce what we call art.” [36] In other words the meaning of an image is both about its alterity to that which is represented (in which a large number of changes and divergences impact meaning) and the nature of that representation institutionally, socially, personally, etc. As Rancière notes, Sergei Eisenstein could already look to literary history, and Godard to painting history, to get a sense of how film montage impacted the meaning of its constituent images. [37] Therefore, Rancière argues, the “images of art are operations that produce a discrepancy, a dissemblance.” [38] He follows that there are three kinds of image. There is the “naked image” that “does not constitute art” because it “excludes the prestige of dissemblance and the rhetoric of exegeses.” [39] The second kind of image is “ostensive” – an image that “asserts its power as that of sheer presence, without signification.” [40] Of course there can be no image without signification. However, the attempt to create them is a real and fundamental aspect of culture; think of Abstract Expressionism, etc. The third kind of image is what he calls “metamorphic”; a space in which the nature of the artistic distribution and consumption creates a particular sort of image alterity; such as installation-art, the music video, the “performance” of faux Facebook pages, etc. [41]

Rancière is no doubt too categorical – as he himself admits. Think of Burhan Ozbilici’s news photograph of the assassination of the Russian ambassador in a Turkish art gallery. It fits into at least two of these “categories.” As Rancière writes, “it is remarkable that none of these three forms… can function within the confines of its own logic.” They all “borrow something from the others.” [42] As these and other aspects of the “image” bump into one another they also bump into signs of social class. The art space is a theatrical space (that claims not to be one). When Mevlut Mert Altintas chose an art gallery for his performance/assassination it aestheticized his political violence. The theater, unlike the idea of the white cube, poses a radical temporality and reasserts the political and existential. The white cube pretends to stand outside of time. The theater is defined by time. [43] As the stage summons a crowd, Alain Badiou argues, it mimics the state. [44] The theater is existential and political. The white cube pretends to be immortal and without politics.

Both aura and reification need distance. The spiritual weight of ancestors becomes more profound as specific ancestors are lost. It is possible to sell anti-capitalist anti-art Dada “masterpieces” for a few million dollars when their social context has been erased by time. These are related but not entirely identical phenomena.

While the white cube actively (or passively) does these things (valorize and reify) this plays out differently in popular artifacts. The mass produced image acquires aura/distance primarily through time. This also abstracts the image – assuming it was not primarily a product of bourgeois ideology to begin with (in which case time can actually clarify its social content). The inherited visual language, however, just as with the unique art object, can be pushed in multiple arcs. For example, several punk artists conceived of their work as a “return to to the source” to reset rock-and-roll from the “overproduced and indulgent” 1970s music scene – and to democratize its base production. This seeking of value (through the auric) was therefore bound up with punk’s aesthetic riot (its rejection of the ideological and commercial). This return to the source could be progressive or reactionary – depending on what artists saw as the primary problem with 1970s and 1980s music.

To be sure, the spheres of “high” and “low” art are very permeable (and should be as we struggle for their genuine elimination). But their economies, contexts and meanings exist. And each are contradictory. Neither can claim democracy. Neither can be easily dismissed. Each sign points to class, and each combination of signs says something about the artist’s attitude toward class – from high modern set designs in film to bringing “poor materials” (Arte Povera) and “popular images” (Andy Warhol) into the rarefied white cube.

Punk Leveling

Nowhere is aesthetic leveling clearer than in the punk and Hip Hop genres born at the neoliberal turn. And both represent within themselves contradictions of how to approach the question. In punk this included a polarization or tendency toward a fascist right vs. a “socialist” or anarchist left. The following notes will sketch some aesthetic questions based on that history. In this I will borrow from, among others, Ryan Moore’s article “Postmodernism and Punk Subculture: Cultures of Authenticity and Deconstruction.” In Moore’s schema “deconstruction” and “authenticity” both “suffer from a loss of the of the utopian imagination” – and each forms a key plank of punk aesthetics. [45] While I think he is right I prefer the a framework (for my purposes here) of “riot” and “valorization” (or “riot” and “poetry”) – as I think these more accurately represent leveling gestures; without the discursive baggage of “deconstruction” and certain middle-class obsessions re: “authenticity.”

Post-Modernism vs. Zine Culture

There is a tragic/gothic relationship between the “fanzine” and the internet – which it, in form and thrust, heralded. The zine was mechanically reproduced. It was first made possible in the 1930s by the increasingly widespread use of mimeographs – and further democratized by the adaptation of photocopiers in the late 1960s and 1970s. The zine reached its greatest notoriety as part of the punk milieu (from the middle 1970s through the middle 1990s). An aesthetic developed that emphasized a feedback between the the photocopied democracy of DIY creation and the unique subjective gestures of each zine’s creator(s). The zine, in its heyday, exemplified riot and poetry. This chimera doesn’t quite translate online. Whereas the golden age zine sought to negate mediation, little online is truly unmediated. [46]

The key elements of the classic DIY zine are the key elements of aesthetic leveling. One tears down – juxtaposes the accepted constellations of signs against other signs, re-mixes and re-sets the clichéd and reified. The other lifts up – valorizes that (and those) who have been made illegitimate by the disposable processes of neoliberal capitalism. These are mutually reinforcing processes. It is in aggregation that mobs tear down the statues of tyrants. It is also in aggregation that mobs can (under the proper circumstances) free the unique subjectivities of their members from the deformity of class rule. This, again, is differentiated totality – the carnivalesque. “‘[C]haotic design’ of the fanzine page,” “‘chaotic’ in relationship to a graphic relationship of resistance,” Teal Triggs writes, “‘unruly cut-n-paste’ with barely legible type and ‘uneven reproduction.’” [47]

The chaotic quality of this visual resistance was rooted geographically and temporally. Ryan Moore argues that the punk aesthetic was a contradictory response to “post-modernism” – understood as the cultural logic or ideology of the neoliberal turn – a reassertion of remixed metanarratives in a philosophical-cultural context that denied them. [48]

In philosophy and the social sciences, postmodernism is said to characterize the exhaustion of totalizing metanarratives and substitute localized, self-reflexive, and contingent analyses for the search of objective, universal truth… In the art world postmodern style is defined by hybridity and intertextuality… In culture at large, postmodernism describes the collapse of the hierarchies and boundaries between “highbrow” and “lowbrow,” as all cultural products are subjected to the same process of commodification and incorporation, exemplified in the architecture of Las Vegas… In politics the postmodern age signifies the fragmentation of revolutionary subjectivity into a collection of identities and differences, or the dissolution of class politics in favor of the nomads of “new social movements…” [49]

The "post-modern" Las Vegas Strip

At the root of all these changes, their overdetermination, was the neoliberal shift:

…as capital mobilizes all available human and technological resources in pursuit of its ideal condition of instant turnover, minimal labor costs, and the total penetration of global markets, people around the world have experienced a compression of time and space in even the most private dimensions of their personal lies…. Freed from the stability and certainty of traditional institutions and communities, the consuming subject is solicited in all moments and places of everyday life, divided into increasingly precise niches of demographics, taste, and lifestyle, and exposed to a volatile sequence of immediately vanishing signs and images. [50]

The material basis of “post-modern culture,” the neoliberal turn and the technologies associated with it, began to hit critical and political mass in the 1970s. The description above, with two caveats, holds true even so more today as dystopia is lit by the constant presence of digital screens. Two two important caveats are: 1) the working-class subject is not simply a consuming subject, but an (often unwilling) producing-consuming-surplus-labor subject. 2) This condition has become so unbearable that political, totalizing, solutions are now in demand (but in the absence of a genuine left alternative, often ceding ground to alt-right fascists). [51]

In the classical zine period, the aesthetic formation of zine culture was tied to what Moore calls authenticity, or what I see as a related class valorization. Steve Mick, in one the first UK punk zines, Sniffin’ Glue, writes (1976) that “…punks have been telling us we’ve got the best mag around. Well, of course we have ‘cause we’re broke, on the dole and living at home in boring council flats, so obviously we know what is going on!” [52] As Moore notes, “The British economy had begun its downward spiral since the end of the 1960s and by 1975 there were over 1.5 million unemployed workers in the nation, most of whom were castoffs from its deteriorating manufacturing base.” [53] The leveling zine was one byproduct (in both Britain and in the United States). Forty-odd years later social fragmentation, chronic unemployment, low-wages and precarity have only further metastasized. And they have done so in the context of the overproduction of images.

Time Square (New York City) and the abandoned Packard Plant (Detroit, Michigan)

A “volatile sequence of immediately vanishing signs and images” is the basis of Boris Groys’s explanation for the “weak images” of the contemporary “weak avant-garde.” [54] The author of this article has a related but somewhat different take on the “weak avant-garde”:

There is a material basis for the weak avant-garde, both in the political economy of the art world itself, and the broader cultural dynamics of contemporary capitalism... The art market, of course, is what reinforces the middle-class character of visual art production and the commodity status of the art object. The art market economy is largely one of individual producers who make art on speculation to be sold in a boutique market. The vast majority of artists who participate in this market are unable to ‘make ends meet’ by art sales alone. The foundational economy of the art world cannot support the majority of artists. Regardless, the demands of this market, oriented primarily to middle and upper class collectors, tend to shape the content and form of artworks sold. Here is a possible explanation for ‘weak’ images that Groys has missed – a prosaic truth that much of the bourgeoisie does not want challenging images hanging over their couches. [55]

Nevertheless, ideology and signification also play an important role. Triggs writes:

The semioticians Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen observe a shift taking place in the era of ‘late modernity’ from a dominance of ‘monomodality,’ a singular communication mode, to ‘multimodality,’ which embraces a ‘variety of materials and to cross the boundaries between the various art, design and performance disciplines.’… The music historian Dave Laing, for example, comments upon discourses found in the areas of pornography, left-wing politics and obscenity. Explicit sexual words … permeated the lyrics of punk songs, performances on stage and in the pages of fanzines. All these facets incorporated an explicit and violent use of language as part of a general shock tactic strategy meant to offend and draw attention to punk itself. The DIY approach to fanzine production ensured the menacing nature of the words in the use of cut-up ransom note lettering. [56]

Moore argues, of course, that the aesthetic resistance of punk to “postmodernity” can be categorized as a drive to “authenticity” on the one hand and “deconstruction” on the other; that the latter dramatizes “the fragmentation of experience” in contemporary life and the former re-asserts a lost sense of the authentic (before all space and time contracted under the weight of capital accumulation). [57] The “authentic” could also be read as a desire for a return to lost partial autonomies (the union hall, downtime at work, disposable income, the independent record store, etc.). All leveling gestures are marked by context and their subjective authors. Punk gestures were “designed to represent the darkness and impending disintegration of British [and American] society, and they fulfilled that prophesy when punks provoked onlookers into fits of rage and violence or became media scapegoats for the downfall of civilization.” [58]

Illustration from Sniffin' Glue (and countless other zines) imploring readers to "form a band" on the basis of three cords.

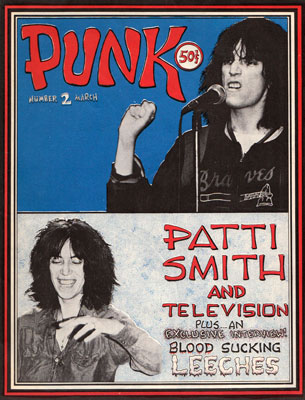

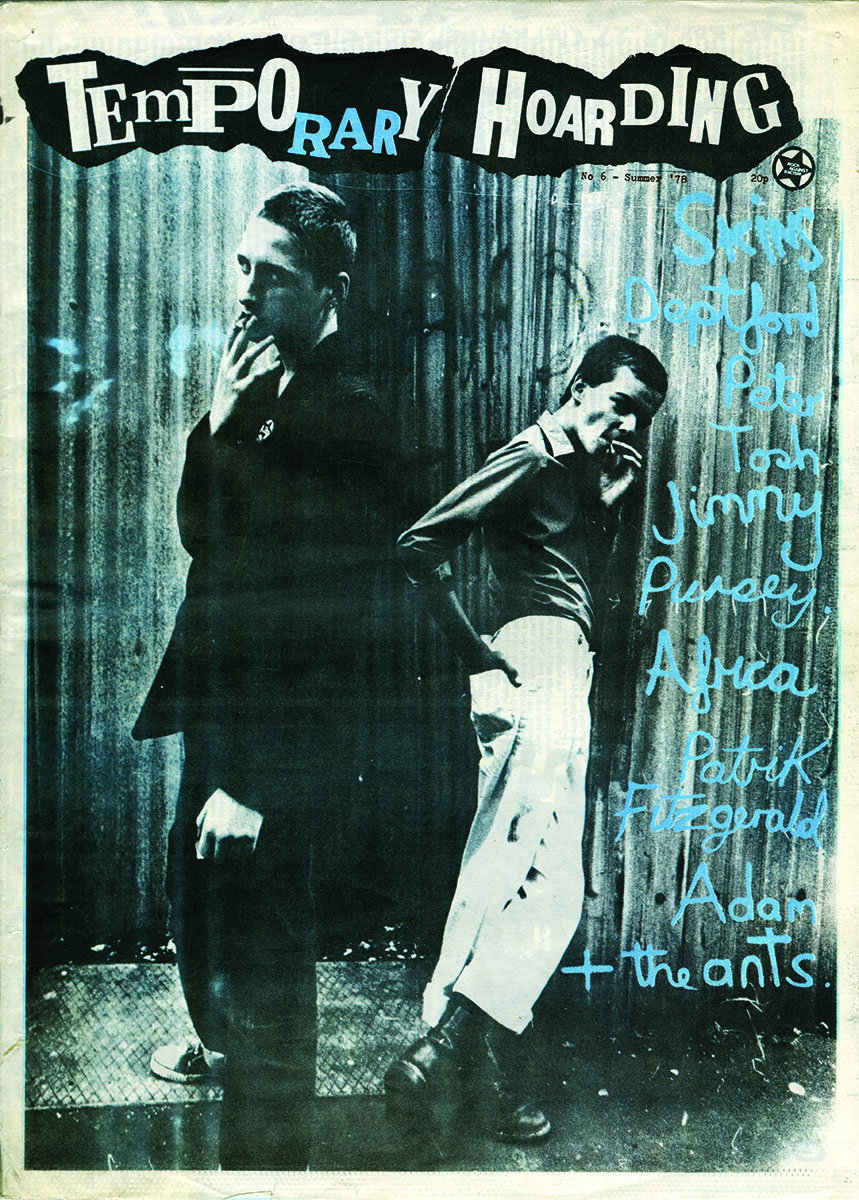

Nevertheless, the DIY ethos, and the aesthetics produced, were a counter-proposal to hyper-commodification, over-production and a dominating corporate culture (in the context of growing class inequality and precariousness). As Sniffin’ Glue’s Mark P. wrote “All you kids out there who read ‘SG’ don’t be satisfied with what we write. Go out and start your own fanzines.” [59] Sniffin’ Glue published a “now famous” DIY illustration teaching their readers how to play three cords with the printed directive: “Now Form a Band.” [60] Likewise, there was a mushrooming of zines – from Slash in Los Angeles, Punk surrounding the CPGB bands in New York, to Temporary Hoarder (associated with Rock Against Racism in London). This was reproduced ten-thousand times over in the coming decades. And many of these Xeroxed artifacts became, in essence, proletarian fetishes – records of the performance of rebellious, often contradictory, working-class lives.

Endnotes

Perez Zagorin, Rebels and Rulers, 1500–1660. Volume II Provincial rebellion. Revolutionary civil wars, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982) 164 and Whitney Richard David Jones, The Tree of Commonwealth 1450-1893 (Fairleigh Dickinson Universituy Press, 2000), 133, 164

Of course this volatility has become less visible in the post-modern period. As post-modernism was the cultural logic or ideology of neoliberalism, and because neoliberalism was the rule of the center, the institutional avant-garde has avoided radical poles. This center will not hold.

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 5

See Walter Benjamin, Illuminations (New York: Shocken Books, 2007)

See Enzo Traverso, Fire and Blood: The European Civil War (New York: Verso, 2017), 24-25

This should not be confused with the “horseshoe” theory.

“Rock Against Communism” was the National Front’s Response to “Rock Against Racism” in the late 1970s and early 1980s in the United Kingdom.

Ben Davis, 9.5 Theses on Art and Class (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2015)

Enzo Traverso, Left-Wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, And Memory (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 128

Traverso, 132

Traverso, 138

Traverso, 139

Rucgard J. Golsan, editor, Fascism, Aesthetics and Culture (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1992), 235 and Roger Griffin, Modernism and Fascism (New York: Palgrave MaccMillan, 2007), 152-153

Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings Volume 4, 1938-1940 (Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), 234-235

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations (New York: Schocken Books, 2007) 263

Benjamin, 260

Traverso, 132

Traverso, 132

Alan Antliff, Anarchy in Art: From the Paris Commune to the Fall of the Berlin Wall (Vancouver: 2007), 22

Antliff, 22

Antliff, 25

Antliff, 26

See Benjamin’s “On the Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in Illuminations (New York: Shocken Books, 2007)

Antliff, 28

Antliff, 30

See Ernst Fischer, The Necessity of Art (New York and London: Verso, 2010)

Antliff, 23

Antliff, 23

Linda Nochlin, Courbet (New York and London: Thames and Hudson: 2007), 19

Nochlin, 20

Nochlin, 24

Nochlin, 27

Traverso, 137

Nato Thompson, Culture as Weapon: The Art of Influence in Everyday Life (New York: Melville House, 2017), viii

Thompson, x

Jacques Rancière, The Future of the Image (London and New York: Verso, 2007) 7

Rancière, 7

Rancière, 8

Rancière, 22

Rancière, 23

Rancière, 23

Rancière, 26

Alain Badiou, Rhapsody for the Theatre (London and New York: Verso, 2013), 11

Badiou, 2-6

Ryan Moore, “Postmodernism and Punk Subculture: Cultures of Authenticity and Deconstruction,” The Communication Review Vol. 7 No. 3 (2004), 323

Teal Triggs, “Scissors and Glue: Punk Fanzines and the Creation of a DIY Aesthetic,” Journal of Design History Vol. 19 No. 1 (Spring, 2006), 69

Triggs, 70

Ryan Moore, “Postmodernism and Punk Subculture: Cultures of Authenticity and Deconstruction,” The Communication Review Vol. 7 No. 3 (2004), 305

Moore, 306

Moore, 306

To be fair Moore wrote the above before the 2008 financial crisis when the U.S. was still the global market’s “importer of last resort.”

Triggs, 72

Moore, 310

Boris Groys, “The Weak Universalism,” e-flux (April, 2011)

Adam Turl, “Against the Weak Avant-Garde,” Red Wedge Magazine (April 5, 2016)

Triggs, 73

Moore, 307

Moore, 311

Moore, 314

Moore, 314

This essay appears in our third issue, “Return of the Crowd.” Purchase a copy at wedge shop.

Red Wedge relies on your support. If you like what you read above, consider becoming a subscriber, or donating a monthly sum through Patreon.

Adam Turl is an artist and writer who lives in Las Vegas, Nevada and St. Louis, Missouri. He is an editor at Red Wedge Magazine and is an art critic for the West End Word. Turl's recent exhibitions include Thirteen Baristas at the Brett Wesley Gallery in Las Vegas, Nevada, Kick the Cat at Project 1612 in Peoria, Illinois and The Barista Who Could See the Future, as part of Exposure 19 at Gallery 210 (St. Louis, Missouri). In 2018 he will be exhibiting Revolt of the Swivel Chairs at The Cube (Las Vegas, Nevada). In 2016 Turl was a resident at the Cité internationale des Arts in Paris. He is an adjunct instructor at the University of Nevada - Las Vegas.