Last year was mostly shit. Remnants of the Arab Spring were consumed by the mutually reinforcing dyad of ISIS and U.S. imperialism. Black bodies lay in the streets of every major American city; murdered by racist police. Whatever you think of Bernie Sanders the life-blood of Occupy has been directed, again, into a bourgeois electoral process designed to demobilize activists. SYRIZA betrayed the Greek working-class and the international left (that had placed so much hope in it). Of course, there are glimmers of hope: the re-election of Kshama Sawant; Jeremy Corbyn’s (Trotskyist, Maoist or Stalinist, pick one) plot to “take over the Labour Party” that he was democratically elected to lead; Black Lives Matter activists are pressing forward… What follows here, however, is not some sort of socialist perspectives-in-disguise. Instead it is my reflection on some of the cultural, artistic and critical products/ideas of the past year (or so); each that I believe are good in their own right, but will also help orient cultural Marxists. What blood-addled revenges and carnivals will we seek in the ruins to come?

1. The artists of Black Lives Matter

As the protests against racist police abuse and murder continue, most recently in Minneapolis following the killing of Jamar Clark, and the police shootings and cover ups in Chicago, artists keep rallying with the cause, producing work for protests and galleries, as they have done since the struggle exploded in the wake of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri.

2. Salvage

The founding of Salvage (edited by Rosie Warren with China Miéville and Richard Seymour, among others) is more than welcome, because, as Salvage argues in their introductory perspectives, “the messianic moment of Marxism has been and gone. Because history was not redeemed.”

“There was always a glow at the horizon, a Red sublime, now veiled by rubbish fires, there is still a glow at the horizon. But it has gone from being that of a sunrise to that of a sunset, without ever passing through day.” “No this is not midnight of the century, But it is a long dusk. We require, in this half-light, a crepuscular Marxism.”

3. More Sweetly Play the Dance (William Kentridge)

South African artist William Kentridge has been very busy, working on performances, installations and videos (of his charcoal animations) for display in New York, China and Australia. This December, in London, his video More Sweetly Play the Dance (projected across eight screens) opened at the Marian Goodman Gallery, depicting an imagined refugee crisis. Interestingly, or tragically, this was not done in response to the current outflow of human beings from Syria and the Middle East. Kentridge began planning the installation several years ago, an imagined response to the horrors his childhood in apartheid South Africa primed him to see.

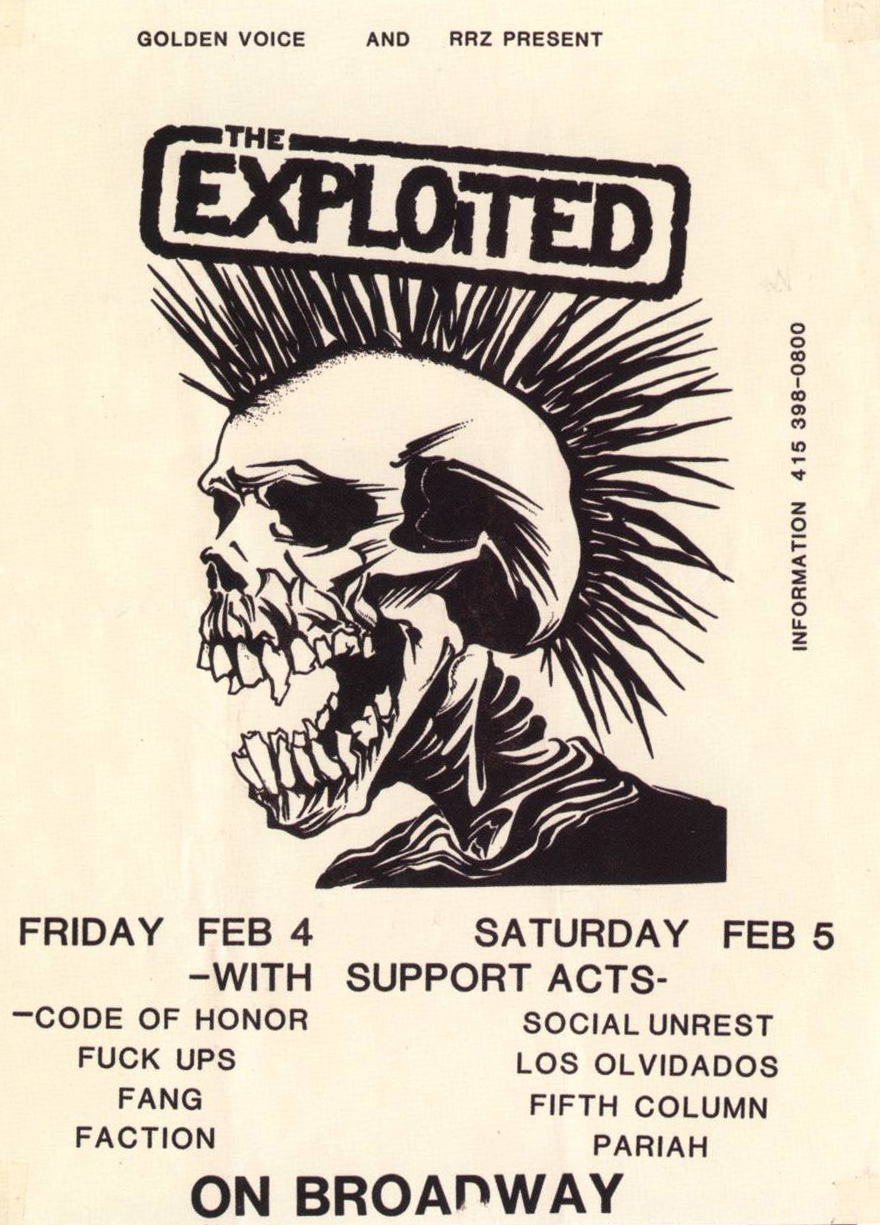

4. Fucked Up + Photocopied (Bryan Turcotte and Christopher Miller)

Back in my early youth, let’s say it was before the Internet, we used to make zines, making collages, writing insane declarations, mostly ranting against anything that seemed hypocritical, oppressive, exploitative and/or banal, and then staying up all night at Kinko’s producing booklets to issue into the various abysses of my hometown. I helped make one with my friend Warren called Schwag (our homage to free propaganda and shitty marijuana), KioskSoviet (a late adolescent attempt to have a socialist revolution in heaven or something), and zines for the Corrosive Art Shows at the Douglass School in Murphysboro, Illinois. There was an inherited aesthetic in all that; borrowed (often poorly) from the 1970s and early 1980s punk milieu; itself the origin of the zine, bound up with crude punk music posters: cheaply produced, black and white drawings and collages, photocopied and plastered about.

Bryan Ray Turocotte and Christopher Miller’s Fucked Up + Photocopied: Instant Art of the Punk Rock Movement provides a good collection of North American punk’s early DIY art and posters. Originally published in 1999, before the Internet fully eclipsed 1990s zine culture, the book entered its sixth printing in 2015. The anti-gestures of three decades past have now accrued distance, and their own sort of aura. The frustrations of the generation that lived through the neoliberal turn, expressed in these posters, have become a gothic echo. One cannot be simply nostalgic for that time. The posters express the volatility of punk’s anti-everythingness; its tendency to break both to the left and the right, to undermine gender binaries but also reinforce machismo, etc. But that moment, a proletarian genius vs. the crises of working-class towns and neighborhoods, is embedded in these artifacts.

5. Television turns toward a novel form

A few decades ago it was predicted (by some) that society was on the verge of becoming a visually oriented but aliterate dystopia. This prediction seemed to fit, in a way, with the increasingly easy image production, television shows and blockbuster Hollywood movies of the 1980s and 1990s. But the future turned out to be far more interested in stories and texts than the previous generation’s snobs imagined. Aural communication is giving way to written correspondence (albeit in texting haikus) and story has reasserted itself in four-dimensional media. It is the Hollywood blockbuster, Star Wars aside, that struggles to find footing in the Internet age. It is “television” (really streaming video) that has become a mass space for serious visual storytelling. Only part of this is about technology. The broader cultural turn toward narrative is also born of the “return of history” and all its messiness (inequality, police murder, gentrification, imperial entanglements). A complex but dystopic world needs storytelling for us to make sense of it. It needs mythologies to instruct us (for good or ill). Streaming video and binge watching have started to displace the old television form as well; the flickering light meant to comfort us after enduring real life, the familiar never-ending classical sit-com. Long-form streaming video is something else, more akin to the serialized novels of the 19th century than the static warm emptiness of television’s heyday.

There are many (well, maybe a dozen or so of the thousand plus current shows) artistically worthwhile series. Many of them, however, are objectively conservative. The most obvious is the most popular. The Walking Dead has become, in many respects, a libertarian and Darwinian fantasy world. Shows like Fargo situate the precipitate decline of 1970s and 1980s working-class life in individual moral terms (however well written and produced). Some of the best shows (that place individual crises socially) are Mr. Robot (Sam Esmail), the Netflix adaptations of Marvel’s Jessica Jones (Melissa Rosenberg) and Daredevil (Drew Goddard), and Amazon’s adaptation of Phillip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (Frank Spotnitz). The best politically is the “furiously anti-capitalist” Mr. Robot (Richard Vine, The Guardian), whose main character, a drug addicted hacker responds to the question, “What about society disappoints you so much?” with “Oh, I don’t know. Is it that we collectively thought Steve Jobs was a great man even when we knew he built billions off the backs of children?” The best visually, and in terms of its self-constructed universe, is The Man in the High Castle, imagining a 1960s America divided by victorious Axis powers; a fascist United States that doesn’t seem all that dissimilar to post-war conformism; a world in which anti-Jewish lynch mobs rounded up their neighbors after the war. The best stories, however, come in the noir-laden Daredevil and Jessica Jones; the former against gentrification in Hell’s Kitchen (led by Vincent D’Onofrio’s Kingpin), the latter fighting the personification of rape culture (in David Tennant’s Kilgrave).

6. Three Moments of An Explosion (China Miéville)

China Miéville's new collection of short stories, Three Moments of An Explosion, gives a twisted glimpse on the horrors to come, or a skewed vision of the horrors that are already here; from icebergs that float above London while coral reefs suddenly appear in Brussels, to a festival of people wearing the heads of dead animals only to become infected with an unknown parasite. Miéville's book should be considered a guide for how to tell stories of alterity rooted in the social and class contradictions of the present, invoking the human need for the fantastic, and the distance (and aura) it provides. It is not only brilliant storytelling. It is an argument, in its existence, for what such stories should be.

7. The ongoing revival of Bertolt Brecht

Over the past few years there have been dozens of articles about the return of Bertolt Brecht, and more importantly, productions of his plays continue to pop up like the mushrooms around a dead body. In 2015 Stephen Parker’s biography, Bertolt Brecht: A Literary Life (2014) was published in German. What is most important, for readers of Red Wedge, is what the work and ideas of Brecht can continue to teach us about a popular socialist avant-garde. The distancing techniques of Epic Theater were meant to introduce a contradiction within the play; plays would employ the traditional snares of “high” and “popular” theater (which Brecht often plagiarized outright), and then interrupt them by exposing the inner-workings of the theater itself (asides to the audience breaking the fourth wall, putting the band onstage, exposing the set construction, speeches and songs that seemed to have no connection to the overall plot, etc.). In Epic Theater there are two nods to the popular: the popular concerns of a proletarian audience, and the popular theatrical and narrative devices used. But Brecht did not stop there, much to the consternation of folks like György Lukács. Brecht’s working-class audience is going to rule the world. They are not there to be tricked or deceived (in the larger sense). But they are there to see the theater (to be tricked in the smaller sense). Brecht employs shaman’s tricks (the various artistic and narrative devices of the theater) and then exposes how they work. The result is a pumping of the conscious and subconscious, back and forth, awake and dreaming, repeatedly; from his musical experiments with Kurt Weil (Threepenny and City of Mahogany) to his more didactic plays like Saint Joan of the Stockyards.

8. The November Artists Network

I shouldn’t include the November Artists Network because it is an obvious conflict of interest. But it is an honest conflict. In 2015 a small group of artists from St. Louis, Detroit, Portland, Oregon, Southern Illinois and Pennsylvania came together to start November. The idea was to begin to network with other anti-capitalist artists, socialist or anarchist, to have a space to discuss work, promote each other, without a priori assumptions about what our practice or aesthetic strategies ought to be. We recognized that the organization, work and ideas of radical artists tended to be fragmented, and that we needed to have a modest plan to begin to address that. The members of November include Sarah Levy (Whatever/Bloody Trump), Ian Matchett (PKK, Solidarity), Kelly Gallagher (Pen Up the Pigs, From Ally to Accomplice), Anna Maria Tucker (Lady Mule Skinner), Red Wedge’s Craig Ross (Steal Away; The Visions of Nat Turner), Danica Radoshevich and Adam Turl (13 Baristas, Kick the Cat).

9. Afrofuturism

Since the apocalyptic went mainstream, reflecting the cliché that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, there has been a dearth of non-apocalyptic imagining. The last gasp of generalized cultural futurism came with the growth of the Internet in the 1990s, as popular commentators and obscure theorists alike imagined our cybernetic future. It as if we stopped imagining the future (as anything much more than wasteland) once it became clear that it had arrived. Therefore, the continued growth and influence of Afrofuturism, described by Ytasha L. Womack in Aforfuturism: The World of Black Sci Fi and Fantasy, is of particular importance. Here are a set of ideas and gestures, fusing the cultural and intellectual history of African Americans, the African Diaspora and Black folks generally, with science fiction tropes, futurist ideas, etc. Here is a space for the revolutionary imagination—a space in contrast to, but not in denial of, the bleakness of the present. As with China Miéville's speculative fiction, Afrofuturism tends to fuse science fiction and fantasy in both literature and visual arts.

10. Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: New Paintings (Pace, New York City)

Emilia and Ilya Kabakov invented, more or less, the idea of total installation, “the viewer surrounded on all sides,” who “loses his or her freedom, feels trapped and becomes its victim.” This is not a pleasant art, as beautiful as their work may be, it is a reproduction of the condition of proletarian life, albeit fantastically, within the art space. Ilya Kabakov, once a part of the underground Moscow conceptual art scene in the latter years of the Soviet Union, borrowed these ideas from the “total installation” that was the USSR (Boris Groys): an entire nation pretending to be run by the working-class, pretending it was one thing, trapping its citizens in a false reality. Ilya and Emilia Kabakov are not socialists, predisposed by their experiences to be circumspect of “utopias.” But they also miss them. “First comes enthusiasm, then reality,” Ilya says, “then pessimism and then nothing, cosmic emptiness… and then the cycle begins again.” The constraint of everyday life is a constant for the working-class, although its nature in the USSR was of a different order than in the social democratic or liberal west. “When the father has beaten up the child everyday,” Ilya says, the child “takes a book and goes into the corner, to hide there and disappear into the world of fantasy.” In the fantasies of the Kabakovs, the child recreates their imprisonment, and in that world defeats their tormentors (in one way or another).

11. The Ancients and the Postmoderns (Fredric Jameson)

Whatever you think of Fredric Jameson, he was one of the first Marxists to understand what “postmodernism” was and remain a Marxist. Maybe he is sort of like Indiana Jones. He was there with the Ark of the Covenant but it didn’t burn off his face, the way it did most everyone else, keen as they were to make tenure by denouncing Marxism. Jameson’s latest collection of essays, The Ancients and the Postmoderns, sees contradictions that most of us would miss: how Robert Altman’s Shortcuts (set in a nondescript Los Angeles suburbia) contradicts its source material (Raymond Carver’s short stories of hard drinking and despair very specifically set in the Pacific Northwest); how elaborate baroque church building can be read as counter-reformation propaganda (and therefore an early modern mass communication); how the films of the (brilliant and underrated) Greek auteur Theo Angelopoulous stretch time in contrast to the highly condensed unfolding of the Greek class struggle; or how The Wire, with its lack of a traditional modern “main character” (Jimmy McNulty notwithstanding) operates on an epic basis.

Ulysses' Gaze (Theo Angelopoulous)

12. "The Heroic Deed: Myth and Revolution" (Doug Greene)

There is, unfortunately, a strand of positivism in some Marxist thought; a belief, even among some of the best Marxists, that science reigns in all things. We know, of course, that a genuine Marxist understanding of human development must make room for the unknown, and for the seeming randomness of individual subjectivity. As an editor at Red Wedge I am proud of the overwhelming majority of articles that we have published. But one article last year sticks out for me; Doug Greene’s essay on “Myth and Revolution.” Doug begins unpacking the basic ideas of Joseph Campbell (the American academic who spent much of his career analyzing mythologies). It is true that Campbell could be a reactionary; he was not a radical, and not even always a liberal. But one cannot dismiss all his observations about the dynamics of comparative mythology by simply noting his stupid private anti-Semitism. Besides mapping the contours of various myth structures from multiple social contexts (although Campbell didn't understand their material origin), he identified the fundamental function of myth (which predates the false consciousness of class societies). It is not about being true or false. Myths are stories that tell you how to move through the world (rightly or wrongly). Greene then goes through the writings of Marxist apostate George Sorel, Peruvian Marxist Jose Carlos Mariategui, Louis Althusser, and others on the dynamic between myth and proletarian revolution.

“Neither Reason nor Science can meet the need of the infinite that exists in man,” Mariategui argues, “Reason itself has been challenged, demonstrating to humanity that it is not enough.”

Or as Greene puts it:

“The struggle entails a vanguard infused with the ‘myth’ of a new egalitarian society freed of exploitation and oppression. It is that ideal, not the texts of Marxist theory or science, that allows revolutionaries to endure prison, man the barricades, sing songs, and march together against impossible odds.”

Che Guevara

Adam Turl is an artist, writer and socialist currently living in St. Louis, Missouri. He is an editor at Red Wedge and an MFA candidate at the Sam Fox School of Art and Design at Washington University in St. Louis. He writes the "Evicted Art Blog" at Red Wedge, which is dedicated to exploring visual and studio art. His most recent exhibitions were Thirteen Baristas at the Brett Wesley Gallery in Las Vegas and Kick the Cat at Project 1612 in Peoria, Illinois.