The ‘20s and ‘30s of post-revolutionary Russia was a dynamic time in which Soviets refashioned their entire socio-cultural program on a massive scale. Factory designers, workers, and consumers, engaged with state ideology to shape a design tradition that is historically unique and had a lasting impact. For a brief period after the October Revolution of 1917, dedicated and idealistic Soviet artists labored over designs and methodology in order to transform the material of the masses. They turned everyday cotton into the stuff that modern day designers dream of. The textiles they produced however only partially reflected the proletariat‘s needs and desires and in many cases fell short of what the new consumer class direly needed, which was functional clothing fabric. Consumer reception to design trends such as abstract patterns and thematic motifs varied significantly, teaching the industry new lessons in mass marketing.

In reality, it took over a decade for the post-war textile industry and its designers to consider designing for the tastes rather than solely the needs of the proletariat. This lack is partially responsible for a gap in the discourse on Soviet consumers’ response to design. The designers were not writing critically about consumerism and the media was not assessing the merits of the designs upon the consumer. Designers and manufacturers own words help us here to understand the industry’s motivations in relation to the needs of the proletariat. Significantly, the textile industry was among the most successful Soviet socialist economy enterprises in that it more successfully wed the design process to manufacturing.

Women on strike in Petrograd on International Women's Day February 23rd, 1917 demanding an end to war and an increase in food.

World War I had raged for over three years by 1917. Fatigued by participation in a costly war, the Russian masses were experiencing their own considerable internal upheaval due to a growing socialist consciousness. Arguably, a female textile worker’s strike on Women’s Day, February 23, 1917 ignited the February Revolution.[1] Massive strikes and demonstrations ensued, launching the Russian Revolution and resulting in Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication of the imperial throne to a provisional government.[2] At the same time, Vladimir Ulianov (later known as Lenin) and the Bolshevik party gained popular support. By October 1917, a coup d’etat known as the October Revolution enabled Ulianov and the Bolsheviks to take control of what then became Soviet Russia.

Among the many changes that took root was a concentrated effort to fully nationalize all Soviet industries, and one of the earliest nationalized industries was textiles. The larger of these factories were particularly seen as the sites of capitalist exploitation and symbolic of individual greed. Private owners either fled or stayed on as employee-managers. The country’s sizeable and historic textile mills such as Trekhgornaya Manufacturing (established in 1799) and especially those in the Central Industrial Region[3] were nationalized within a year of the October Revolution.[4] The textile industry of old imperial Russia, the largest industrial employer before World War I, was in store for a Bolshevik makeover.[5]

The four years following the October Revolution were fraught with civil war, famine, disease, and fuel shortages, resulting in industrial halts and massive depletion of urban populations as people migrated to southern regions for cottage industry and food. This was a major period of hardship in which eight million human lives were lost not to mention significant loss of agriculture and livestock. Owing primarily to the ending of the civil war in 1920 and the end of severe famine in 1922, the Soviet Union was founded under the control of the Communist Party.[6] By this time, over eighty percent of the Russian populace was peasants.[7] As a result of these ongoing conditions and pressures for change, Lenin had launched in March, 1921 a state capitalist or semi-capitalist program of economic development called the New Economic Policy. Its primary purpose was to increase trade and small scale commercial development through the encouragement of goods up-trading for profit. The imbalanced outcome of this arrangement was an overall improvement of conditions in the urban areas but a slower development for farmers and peasants. A new collaboration between artists and manufacturing also began to take form.

Varvara Stepanova. Models and furniture designs for Alexander Sukhovo-Kobylin’s play The Death of Tarelkin, 1922. © Rodchenko Stepanova Archives, Moscow

A few committed artist-designers who were promoting Productivism, scientific design and manufacturing for the socialist cause, began working in the same factories as the well-trained textile factory workers. In the late fall of 1923, Liubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova, avant-garde artists in the first decade of the century, started working for the First Factory of Printed Cotton in Moscow.[8] They were no strangers to color and composition since they had been producing designs in alternate forms since the teens. Popova had been working as a painter, poster designer, and theatrical stage designer until her arrival at the factory studio. Stepanova however, was the only avant-gardist designer entering the field of textiles at that time who had any professional industrial design training. These women along with others like Ol’ga Rozanova (an adept Suprematist), Nadezha Lamanova, and Liudmila Maiakovskaia had a wealth of tradition in Russian applied arts of textile and fashion to build on. They were particularly practiced or at least conversant in embroidery, weaving, dyeing, modernist fashion, and theatrical costume design.[9] Some were also developing new techniques. Maiakovskaia, a pioneer of the “aerograph” technique of textile airbrushing, had been working in the Trekhgornaya Textiles workshop since 1910 and created exclusively abstract and technically advanced work.[10]

Varvara Stepanova. Models and furniture designs for Alexander Sukhovo-Kobylin’s play The Death of Tarelkin, 1922. © Rodchenko Stepanova Archives, Moscow

These early avant-garde designers quickly discovered that there was little commonality between their designs and what was currently being produced at their factories. They designed geometric patterns as a uniquely Constructivist and Soviet response to exotic motifs they perceived as bourgeois, yet the factories were printing pastiche motifs from pre-war times. Most textile designs in Russia up to the 20th century’s political unrest were borrowed or inspired from Parisian pattern books that offered floral designs, historical depictions, and wildlife.[11] The newly arrived designers argued both in and outside the factory that patterning from the imported references projected a uniquely European class sensibility incongruent with the values of Socialism. They, along with other proponents of geometric patterning, believed that their designs had a universal appeal and could not be associated with class because they were non-representational.[12] Indeed, their designs were generally well received by critics who praised not only the patterns but their appropriateness to the fabric. The press reported: “The marquisette and indienne have not only become refined but have risen to the level of an extraordinary art in a period just as extraordinary; the intense colours and vibrant artistic decorations flow like interminable rivers through cities right across the frontiers of our immense Republic.”[13] However, this critical praise didn’t echo the public’s opinion of the patterns, which were generally not favored.

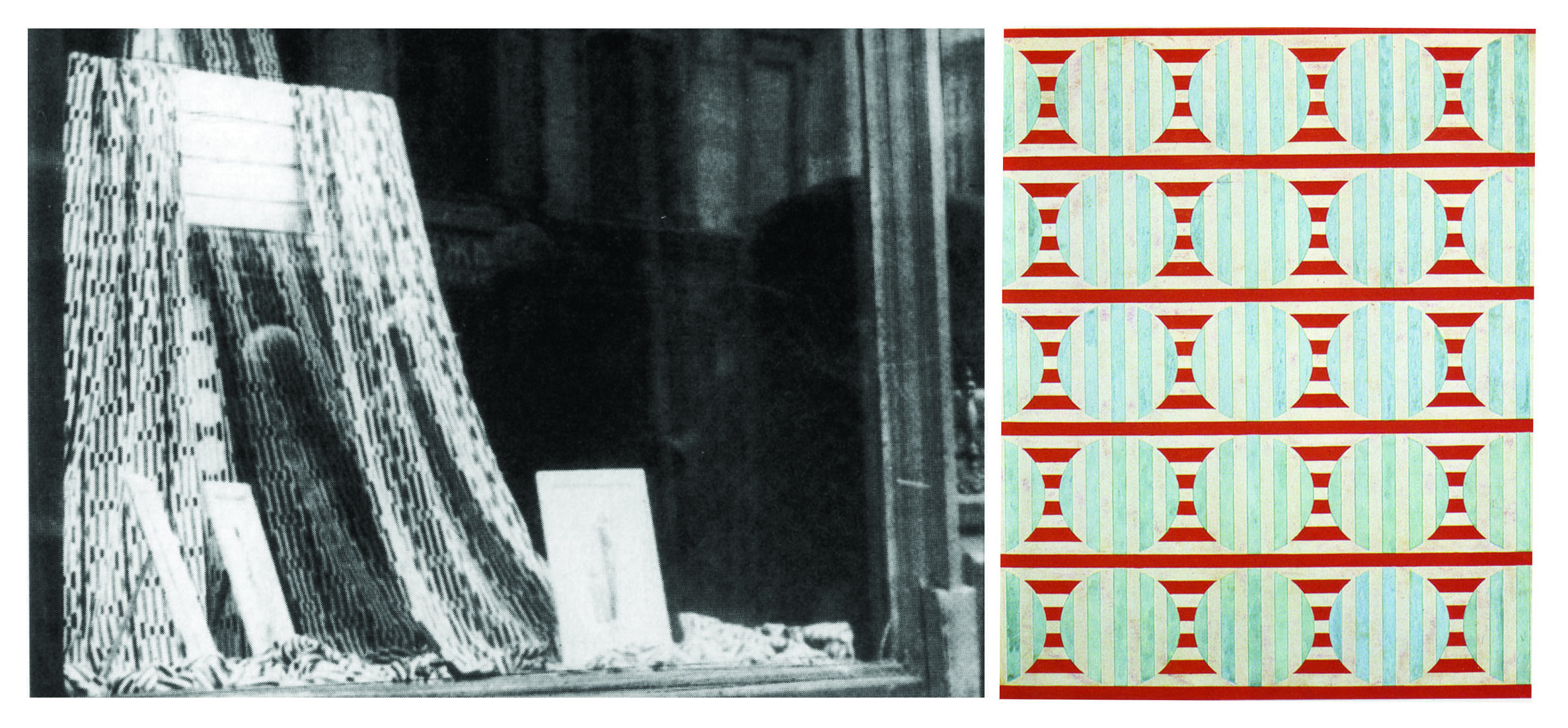

Fabric store display window showcasing textiles designed by V. Stepanova, 1924 (left). Stepanova. "Optical" design for fabric, 1924 (right).

Stepanova and Popova enjoyed continued influence in avant-garde art circles. For example, they had an interest in the kinetic effect of geometric patterns in movement which compelled them to pursue clothing design as a way of creating true over representational movement. This was one intellectual and artistic rational for their designs. However, they were caught between intellectualism and the factory floor. Their colleagues at conferences were calling for radical clothing approaches like throw-away garments, dressing garishly, or going nude, while factory management continued to produce outdated and traditional textile designs. The designers understood that they had to conceptualize and develop a proletarian-appropriate garment.[14]

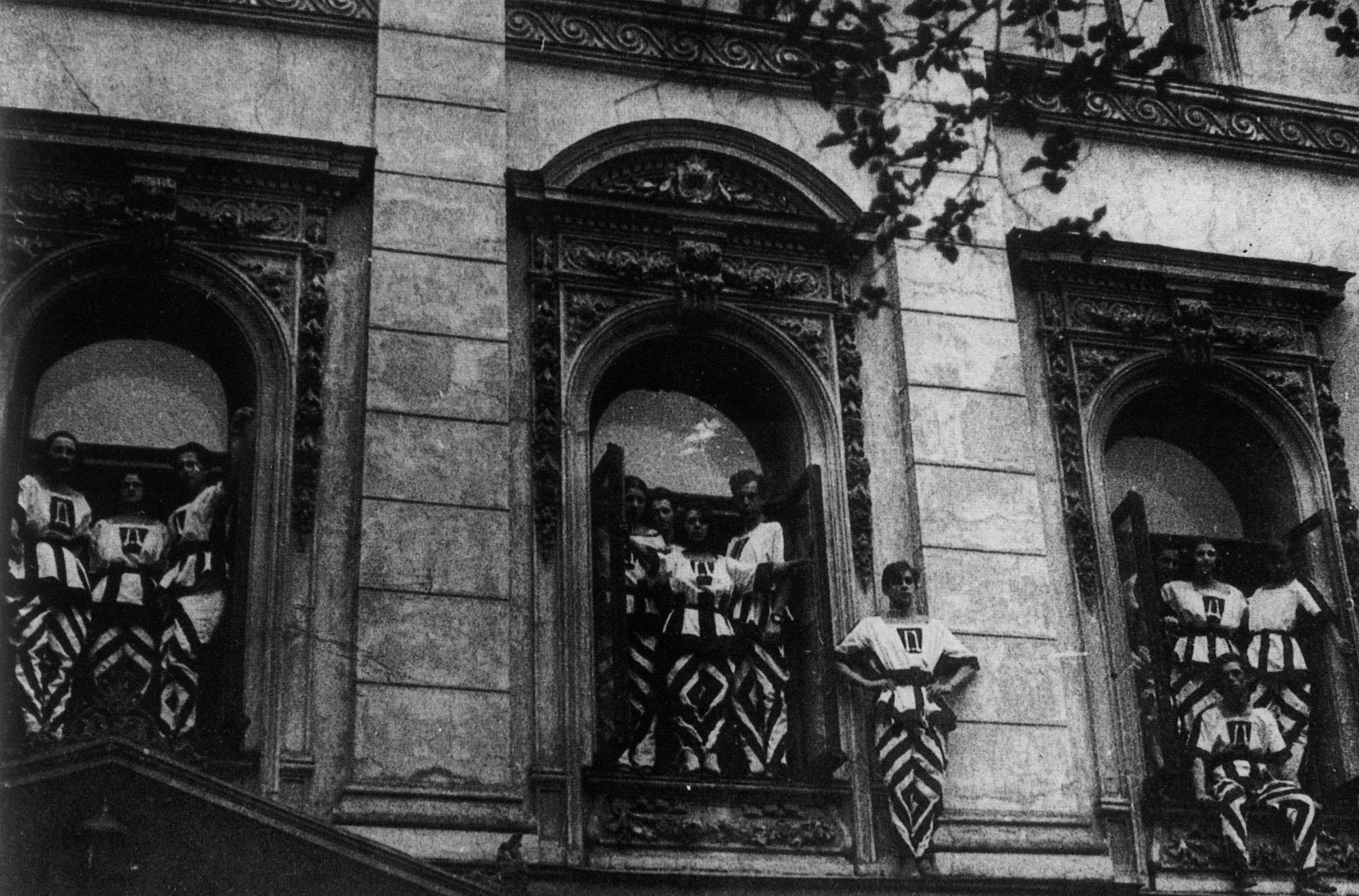

Under this self-made charge, and in response to an expanded debate on national dress, they designed clothing to suit the particular jobs and activities of the new Soviet citizen. The healthy and energetic working class could potentially have outfits for every occasion such as industrial work clothes, sporting garments, or specialized labor uniforms. Stepanova’s garment designs for competitive sports (sportodezhda) were the most successful in that they were light, bright, and used minimal fabric.[15] They were fashioned using principles of comfort, ease of use, and distinctiveness. Emphatic tones and bold lines enabled teams to be easily distinguished from each other.[16] By 1922, there was some consumer interest in industrial clothing (prozodezhda)[17] as reported by the Soviet press in that “people have fallen out of love with Bakst [a leading Russian fashion designer of international renown] and have fallen in love with industrial clothing.”[18]

Academy of Social Education students, dressed in clothes designed by V. Stepanova, readying for a sports demonstration, circa 1923.

The factory-based designers also found time to teach and their pedagogic role helped set them apart from capitalism. For example, they educated a new front of young designers at design schools like the Higher Technical Institute of Moscow. With a new generation came new ideas. By 1928, students were moving in more symbolic and representational design directions. This was an intentional divergence from what they saw as lefty avant-garde concerns with universality, something which was not in service to proletariat needs. Textiles were seen as a ready vehicle for the political rhetoric of the young Socialist in a manner similar to graphic design and other forms for agitprop. Unlike Stepanova, Popova, and Rozanova, younger designers were convinced that a particularly Soviet-themed visual language could and should be developed. The students began promoting thematic graphics that would edify, refashion, and support the proletariat in becoming the ideal Soviet citizen.[19] The values of nationalism, communality, industrialization, modernization, and youthful vigor were expressed in their proposed motifs exemplified by hammer and sickle, laborers, gears, smoke stacks, and bicycles.

This approach to propaganda (agitaciony)[20] through textile was publicly promoted for the first time in October, 1928 by a group of artists from both within the school and unaffiliated. The exhibition Soviet Textiles for Daily Life, took place at the Moscow institute, and was a significant display of textile work by both generations. The event was timed to coincide with the beginning of Stalin’s first compulsory industrialization initiative known as the Five-Year Plan. Exhibitors included textile factories and their designers, sales agents, schools, students, and working faculty members such as Stepanova and Maiakovskaia. Over fifty of the institute’s textile students exhibited, most of who were women comprising one third weaving students and two thirds in printed fabrics.[21]

The exhibition was intended as a launch pad for envisioning and enacting increased textile productivity in order to meet the expectation of the Five-Year Plan, while also jolting production in response to major fabric shortages up to that point. The organizers of the exhibition held hope that the event would inspire the establishment of a consolidated (or central) national design house as an arm of the All-Union Textile Syndicate (an affiliation of factories and an administrative body). In their minds, this would reduce the inefficiency of each factory’s design studio producing artwork for approval and the related lag in demand-to-market response. All design work could be centralized and handled by one national studio, thus also eliminating the need for dependence on French design books and hence foreign influence.[22]

The Textile Syndicate had been founded in 1922 primarily to handle the major concerns of the newly revived, post-civil war industry. For example, production capacity and overall operation of textile factories had been depleted by over two thirds between World War I and the end of the Russian Civil War (1914-1922). And alarmingly, from 1922-1923 most textiles had no designs on them at all.[23] It was not until the later part of the 20s that production began to increase.[24] It was the Syndicate’s primary purpose to address these shortfalls. It was also responsible for assessing factors that would enable increased importation of raw materials like wool and cotton in order to increase fabric production and also to develop export to many Central Asian countries.

Upon graduation, some print textile design students began working in the factory studios. What followed was a period of both experimentation and productivity, though in reality production of the new thematic designs was very low due to unpopularity. Many of the newly arrived designers were not satisfied with the role that the individual factory studios played in determining what was and wasn't produced for national consumption. They still wanted the structural changes they had envisioned while at school. They argued that the older generation designers were politically regressive and at times lacking in skill hence, they did not have the capacity to realize the designs necessary for the new Soviet citizen. Many associated the purely geometric designs with leftist deviance.[25] However, members of the Textile Syndicate were concerned that their centralization proposal did not take into consideration quality control issues of design in relation to cloth, appropriate fabric distribution for distinct geographic and cultural regions, and consumer taste.[26] Art historian and critic, A.A. Fyodorov-Davidov introduces the First Art Exhibition of Soviet Domestic Textiles, in Moscow, 1928 with the following excerpted (and ethnocentric) address:

Among the various applied arts, textile design is one of the most important. As a basic commodity, millions of metres of textiles are produced every year for use in all parts of our country, finding their way even to remote areas populated chiefly by bears, to the homes of the most backward of peoples. One of the basic commodities for trade between town and country, textiles are among the first objects from the new culture to reach the backward, outlying areas. […] From this it is evident that textile design has an enormous part to play in changing old tastes, in breaking old aesthetic traditions and habits (along with the ideological ones that are so bound up in them); it is a vehicle for the new culture and the new ideology.[…] The potential of textiles for popular propaganda has long been recognized […] But it is far too crude and naïve a ploy to use textiles merely as bearers of printed pictures, a practice which, unforunately, continues in this country to this day[…][27]

"The Turkestan-Siberia Railroad." Cotton print. Printed at the Red Rose Factory, circa 1930.

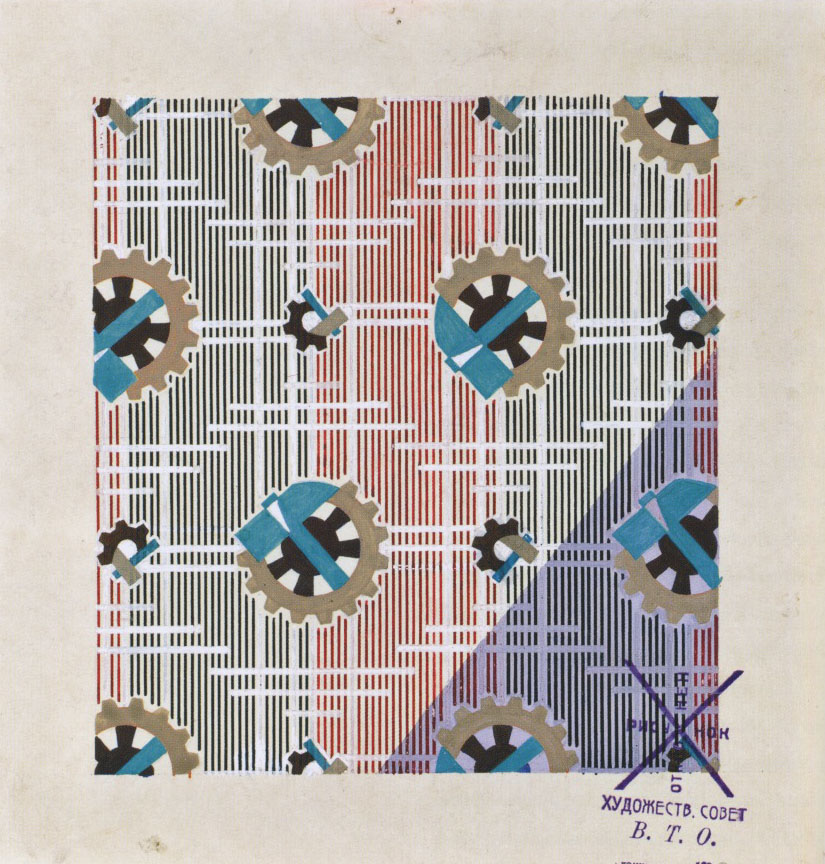

Between 1928 and 1933 designers, historians, artists, and critics continued to wage debates on what constituted appropriate textile design. Their opinions ranged from affirmations that Soviet textiles had ideological influence to calls for the elimination of all design because all style was bourgeois. This later group claimed that the only slogans and text should represent the proletariat (see L. Raiser images).[28] Also, David Arkin, an aesthetic moderate from the Academy of Artistic Sciences, voiced his concern with thematic motifs: “A great quantity of examples can be given where the separate elements of machines – for example, gears, pincers, tools – are depicted on the fabric. These tools or pieces of machines are depicted so that they are not essentially emblems, but illustrate the tendency of many artists and whole trends to elevate machine forms into fetishes or idols. This elevation of machine parts into some kind of divinity is not a proletarian approach to the machine.”[29]

Hammers and gears. (rejected by Artistic Council). Watercolor on paper. Designed for Trekhgornaya Manufacturing. 1930.

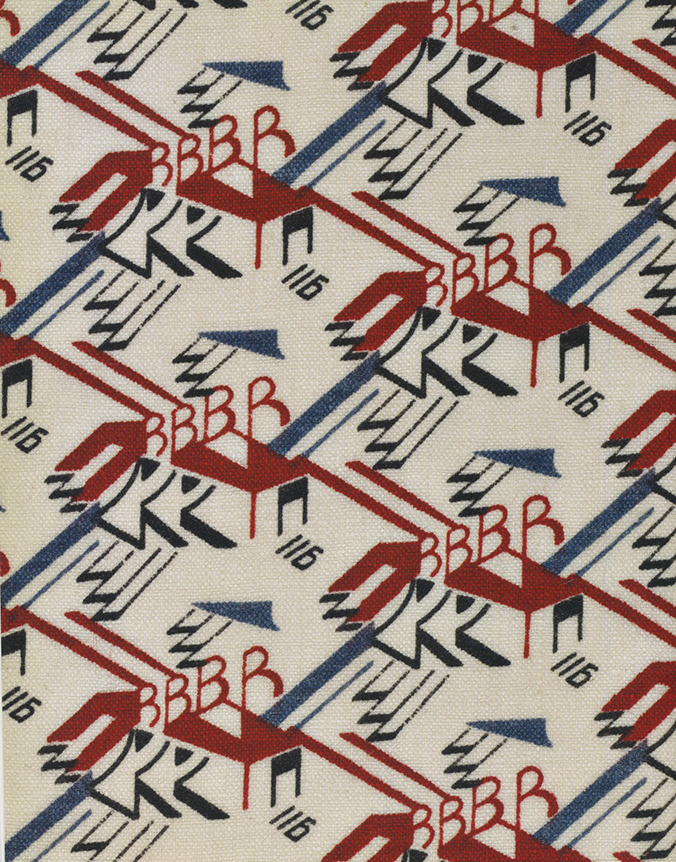

In addition, many of the young artists staged exhibitions and agitated for their cause through organizations, publications, and political jockeying. One exhibition, staged by the Young People’s Section of the AARR (Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia - a union of realists), took place in June of 1929 and featured agitprop and thematic designs.[30] While the new designers continued to lobby unsuccessfully for several years, their own dominance in the factory studios translated to a type of representational voting majority in the Artistic Council (a subcommittee of the Textile Syndicate authorized in design related matters). As a result of this and other factors such as the support of the somewhat regressive yet influential AARR, the young designers were able to forward a de-facto trend in propagandistic textiles.

Lya Raiser. "VKP (B)" (All-Union Communist Party). Cotton print, plain weave, 1929.

Design control favoring propaganda motifs increased during this period. The historian Pamela Jill Katchurin states that “[o]ften the council members would make suggestions about how to improve a particular design, but sometimes they simply rejected it for no obvious reason.”[31] The Artistic Council was also responsible for a historic culling of designs they deemed inappropriate. Between 1929 and 1931 approximately twenty-four thousand designs and drawings were destroyed. They even went so far as to grind off the flowers on printing rollers.[32] To further confuse matters, most of the destroyed patterns were floral yet the council habitually rejected non-representational textile designs. While it would seem that some power from on-high was potentially thwarting good design, the themes and content were not directed or mandated by the government instead the designs were devised by the artists themselves out of response to other design supporting initiatives in the Soviet Union.[33] One can deduce from this that textile aesthetics were heavily driven by artists but ultimately controlled by the Artistic Council who in turn was dominated by a specific group of artists.

This type of privileging had unfortunate effects on production and consumer access. Factory based designers who were resentful that their designs had been rejected by the council slowed the production process by inaction on the designs that had supplanted their own.[34] Nonetheless, some Soviet-themed designs made it through the production lines but at a reduced capacity due to infighting. Up to this time and including the Five-Year Plan period, little fabric was produced other than for clothing.[35] With the increase of the urban population by nearly twelve million people between 1928 and 1932, a new proletariat who had previously been agricultural workers had transitioned to industrial labor. This meant that old ways had to be shed and new ones put on.[36]

Kachurin points out that at this time the workers of the Soviet Union become “walking billboards” as they don garments made from specially printed textiles. In addition to pillowcases, bed sheets, curtains, and other household fabric, they wear motifs such as tractors, smokestacks, laborers, and electricity poles.[37] However, from the onset of the thematic designs around 1928, Soviet consumers were generally apathetic and avoided them. In addition to rejecting thematic motifs, Soviet youth in particular were loath to the plain and unattractive colors of the uniforms they needed. This is made apparent in the following Young Communist League Article of 1928:

Sewing workshops, both private and cooperative, are unable to meet the orders for men’s and women’s Jungsturm [youth] uniforms which are pouring in from all sides.

This is marvelous! […] However, this raises a whole series of questions; Is this fashion what is required? Is it beautiful? Will it fit into the system of cultural and educational activities of the Komsomol? It is definitely not beautiful. The monotonous khaki of the skirts, breeches and shirts, the style of the men’s shirts and women’s skirts, what they wear on their heads – none of this is particularly attractive, and this is chiefly because it is not absolutely what is needed.[38]

This overall apathy and demand of the consumer was fuel for the ongoing debate between the young designers, the factories, and sales people. In fact, most representatives eager for industry growth cited poor consumer appeal and ideological stubbornness on the part of the artists as the reason for needing greater variety of designs.[39] In 1931, the critic A. Fedorov-Davydov charged that the Soviet themed motifs were in fact not so inspiring for the populace:

"Spools and Bobbins." Watercolor on paper. Designed for Trekngornaya Manufacturing, 1930.

all attempts to sovietize the textile design for garment fabrics… have been confined to a very narrow choice of themes, in most cases lacking in any socio-political trenchancy. At best the subject is a rather naïve one – a Poineer, a Red Army man on skis[…] Pioneers on a piece of fustian the Trekhgorniaia Manufactory repeated endlessly in a single figure lose all representational value… Or take the so-called industrial motifs: ‘spool and bobbin.’ Firstly, what’s Soviet about them? Why does a mere tractor have to be a Soviet theme? There are actually more tractors in bourgeois America than in the USSR.[40]

Factory to farm fabrics

Meanwhile, the proletariat had the option of using or not using textiles with a simplistic and idealized array of motifs which can be loosely thematized as: Industry (belts, gears, and smokestacks), Transportation (planes, trains, and automobiles), Energy and Communication (waves, light bolts), Youth (exercising children, balls, drums, horns, and education), Agriculture (tractors, sickles, wheat, and combines), Sports and Hobbies (rackets, balls, bicycles) and Military and War (tanks, weapons, explosions, army personnel, and ships).[41] While it would be worth analyzing all of these themes more to understand how each related to consumer experience, those richest in both potential and problem for the consumer were industry and agriculture. We can see the crux of this paradox in the catch-all Soviet symbol of the hammer and the sickle designed by Oskar Grjun, its representation of industry and agriculture joined in harmony. [42] With the onset of the civil-war, the subsequent New Economic Plan, and even the Five-Year Plan, there was little equity between industry and agriculture.

O. Gruin. Hammer and sickle design on decorative sateen, 1924-1925.

While the focus here is on industry and agriculture, it should be mentioned that transportation was an early theme in motif development. Trains appeared as early as 1919 and were particularly popular due to their association with the transportation of raw materials from the rural to the urban environment.[43] Additionally, electrification motifs were a rare instance in which there was congruity with the idealism of the campaign and the actual infrastructural development of the country.[44] Lastly, leisure activities became part of the worker’s schedule only for the first time after the end of the first Five-Year Plan.[45]

The national obsession in the Five-Year plan, intended to crank industry into production overdrive, brought about a fervent proliferation of industrial motifs. Smokestacks were particularly popular as they represented the urbanization of Russia and round-the-clock labor. In fact, it was at this time that that most factories were operating twenty four hours a day, and offering considerable benefits like improved housing and wages to productive workers.[46] Colorful industrial graphics were designed to inspire the worker and motivate newly transplanted peasant labor. However, gears, belts, and hammers only underscored the disparity between urban life and rural. Pictures of ideal working conditions were cruel irony for the semi-literate laborer during a period that was ultimately overcrowded, threatening, and unhygienic.[47]

Motifs promoting agriculture as the foundation of Soviet culture were popular with designers. This is perhaps due in part to an idyllic belief that Soviet agriculture and industry were interdependent. However, Soviet policy in the first Five-Year Plan privileged modernization and industrialization at the expense of farmers. The forced collectivization of farms into kolkhozy starting in 1928 led to considerable resentment on the part of farm owners who had to give up their lands and requisition grain. As a result of this cultural and economic reorganization many farmers protested by killing their livestock and destroyed any surplus crops leading to food shortages and famine.[48] Images of tractors reinforced an urban-based illusion of productivity while in reality farmers only used half of the government granted equipment otherwise in idle. Agricultural themes were a constant reminder of what was not working well. The peasants were sensitive to the government idealization of farm life and deeply resented it. Overall, there was an obfuscation of the circumstances of farm life in most of the agricultural designs. Kachurin notes “[s]ome images presented a rather fanciful view of farm life, while others depicted the blurred boundaries between wheat and machine, their interdependence reinforced by the use of similar colors and shapes for both the organic and the industrial.”[49] The harsh reality of national famine was also ironically subdued with themes of agricultural abundance in which boundless sheathes of wheat and overflowing baskets crowded a textile landscape.

Salespeople and manufacturers pressured designers to appeal to rural and traditional peasant consumers, and as a result, floral elements were sometimes worked in with these themes. The compositions varied from well integrated to incongruent depending on the artist. While it was assumed by many people in the textile industry that Russians were partial to floral prints, art historian Frida Roginskaia said in 1929, “The problem of plant ornament is actually very complex – its solution is ahead of us.” Rejecting that florals are universally attractive, she points out “Actually, of course, this is not so… Naturally, plant ornament should have a large place in Soviet textile design, since a good part of the textiles goes to the peasantry. But it is also completely obvious that in an epoch of transition to collective agriculture, to methods of working the land using tractors and cultivators, to an era of building colossal collective farms, a design with plant elements must acquire a completely different character.”[50]

S. Burlyn, "Tractor." Cotton print, 1930 (left). "Harvesting." Sateen, circa late 20s to early 30s (right).

The end of the beginning

Thematic design ended with the completion of the first Five-Year Plan. It was made official with the government publication in 1933 of Inadmissibility of the Goods Produced by a Number of Fabric Enterprises Using Poor and Inappropriate Design. Some reasons given for the cessation of thematic design were that the public was disinterested in them and the industry’s productivity was being slowed by infighting over the very issue of design appropriateness. Considering that three to four million individuals died in 1933 from famine, it is likely that there were more significant factors at play such as disruption of factory production and product delivery due to health and well-being.[51] Interestingly, the elimination of unmarketable designs also logically coincided with a growing identification of the Soviet citizen as consumer. This in turn led to design being directed more for saleability and use rather than ideals.[52] As a result, this had an unfortunate effect on design although not marketing or production. The standards were considerably lowered to pander to the tastes of the public, who up to that point had been through a lot of hardship. It is possible that the average Soviet wanted familiar designs that were comforting, something that they did not have to intellectualize as in the case of the early geometric work, or be disturbed or wearied by as in the case of the thematic designs. By 1933, the fate for both avant-garde and thematic motifs is sealed in a coffin and put to rest. It seems that the utopian call did not suit the ideals of nationalism.

Farm machinery in motion. Watercolor on paper, 1928-1931.

The conditions of the time should be kept in mind when questioning why the proletariat didn't accept the new textile designs. Soviet life was considerably more dismal than Russian propaganda projected. Similar to the bright and bold floral American prints of the war-time 40s, colorful and iconic Soviet textiles presented a sharp contrast to the realities of day to day urban life in which Soviet citizens experienced food, fuel, and housing shortages on a near catastrophic level. Combined with unhygienic urban conditions and risk of arrest for dissent, consumers found little to sooth them in the textile products coming from the factories. Most of the rural population had been accustomed to traditional floral and geometric motifs up to the revolution. Lenin’s New Plan model of fabric trade for agricultural produce did little to sooth the empty bellies of individuals receiving cloth. Both rural and urban workers were disinterested in propagandistic fabrics representing unrealistic pictures of their life. And, many rural individuals did not find the industrial picturesque that compelling .

By the late 20s, the textile industry had grown to its prewar levels as the largest industrial employer in the Soviet Union. Many of the new workers during the first Five-Year Plan came from rural areas and were unskilled labor. This meant that a significant portion of the population had a direct relationship with textiles on some level. It's possible to argue that people working on these textiles day in and out, might be loath to wear or use them in any manner because they were either tired of seeing them or they reminded them of their labor. Additionally, there had to have been a psychological dimension with the prints in that they overpowered the individual experience of transition in society. In the end, these great experiments in universality and collectivization through textile design failed in the long run because they never took into consideration the psychology of the consumer, and relied heavily instead on ideology. It was as the author John Bowlt calls it, a “paradoxical marriage of haute couture and mass taste.”[53] This inspiring and energetic time in design offers many lessons to learn from. Consumers and design are interdependent and no mass market can grow without the well-being of both.

L. Raitser. "The Mechanisation of the Red Army." Sateen, 1933.

Footnotes

- E. N. Burdzhalov, Russia’s Second Revolution: The February 1917 Uprising in Petrograd. (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1987), 113–25, referenced in Jason Yanowitz, “February’s Forgotten Vanguard: The Myth of Russia’s Spontaneous Revolution.” International Socialist Review 75: Online Journal. January–February 2011. Accessed April 21, 2013.

- Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 2.

- Husband, 167.

- Pamela Jill Kachurin, Soviet Textiles: Designing the Modern Utopia: Selected from the Lloyd Cotsen Collection. (Boston: MFA Publications, 2006), 20.

- Due to its long history, the renowned Russian textile industry had built up to become the largest industrial employer in Russia by 1913 accounting for 29 percent of the entire country’s factory labor force. William Husband, Revolution in the Factory: the Birth of the Soviet Textile Industry, 1917-1920. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 7.

- Ibid., 13.

- Lewis H. Siegelbaum, Soviet State and Society: Between Revolutions, 1918-1929.(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 68, quoted in “New Economic Policy” – Wikipedia, accessed April 21, 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Economic_Policy.

- Christina Kiaer, Imagine No Possessions: the Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2005), 92.

- John E. Bowlt, “From Pictures to Textile Prints.” The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review (3 (1): 311–325. 1976): 312.

- Bowlt, “From Pictures to Textile Prints.” 315, and “Lyudmila Mayakovskaya Jun 21 - Jul 28, 2013,” UK art scene website. New Exhibitions. 2013. Accessed April 19. http://www.newexhibitions.com/exhibitions/id=611®ion=10&exhibition_id=25339.

- Kachurin, 19.

- Charlotte Douglas, “Russian Fabric Design, 1928-1938.” In The Great Utopia: the Russian and Soviet Avant-garde, 1915-1932. (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1992), 635-636.

- D. Aranovic, “Pervaja sitcenabivnaja fabrika v Moskve” (The First Factory of Printed Cotton in Moscow), in Iskusstvo odevat’sja (The Art of Dressing), 1928, n.1, 11, quoted in Tatiana Strizhenova, “Textiles and Soviet Fashion in the Twenties” Costume Revolution: Textiles, Clothing and Costume of the Soviet Union in the Twenties. (London: Trefoil, 1989), 4.

- Bowlt, “From Pictures to Textile Prints,” 315.

- Ibid, 317.

- Kachurin, 22.

- Tatiana Strizhenova, “Textiles and Soviet Fashion in the Twenties” Costume Revolution: Textiles, Clothing and Costume of the Soviet Union in the Twenties. (London: Trefoil, 1989), 10.

- Bowlt, “From Pictures to Textile Prints,” 317, 313.

- Kachurin, 22.

- Strizhenova, 4.

- Douglas, 635-636.

- Douglas, 636-640.

- Katchurin, 20.

- Douglas, 636.

- Douglas, 635.

- Ibid, 640.

- A.A. Fyodorov-Davidov, “The Aims and Purposes of this Exhibition” Introduction to the First Art Exhibition of Soviet Domestic Textiles, Moscow, 1928, as reprinted in David Elliott, ed., Art Into Production: Soviet Textiles, Fashions and Ceramics, 1917-1938: Exhibition Catalogue. (Oxford: Museum of Modern Art, 1984), 93.

- While there are two textile images in this paper by Lya Raiser, at this time, I have not been able to confirm a universally accepted English spelling of this designer’s name. Both print image sources spell it the way I have presented them respectively on the descriptions here. I have also encountered the name spelled “Lya Rajcer” by the Art Institute of Chicago for the textile ”VKP (B).”

- David Arkin, “Risunok-neotemlemaia chast’ kachestva tkani,” Golos tekstilei, March 24, 1931, 3, quoted in Bowlt, “From Pictures to Textile Prints,” 642.

- Douglas, 640.

- Kachurin, 27-30.

- Douglas, 642.

- Kachurin, 30.

- Douglas, 642.

- Ibid, 640.

- Fitzpatrick, 140.

- Kachurin, 16.

- “How Should We Dress? A Discussion – let us have your opinion on the subject,” Komsomol’skaya Pravda (the Young Communist League newspaper) June 30, 1928.

- Douglas 641.

- leksei Fedorov-Davydov in “Iskusstvo tekstilia,” in Izofront. Klassovaia bor’ba na fronte prostranstvennykh iskusstv. Sbornik statei ob’edineniia “Oktiabr’” (Moscow-Leningrad: Ogiz-Izogiz, 1931), 77-78, quoted in Bowlt, 319.

- Kachurin. The author uses these approximate categorizes in her research. However, I have added the category of Military and War because I believe it stands out uniquely from industry and transportation.

- Strizhenova, 4.

- Kachurin, 47.

- Ibid, 55.

- Ibid, 84.

- Ibid, 35.

- Ibid, 37.

- Ibid, 71.

- Ibid, 75.

- F. S. Roginskaia, “Rost khudozhestvennoi smeny v tekstile,” Izvestiia tekstil’noi promyshlennosti torgovli 7-8 (1929), p. 94, quoted in Douglas, 641.

- Fitzpatrick, 139.

- Kachurin, 89-91.

- Bowlt, “Manufacturing Dreams,” 17.

Jessica Allee recently graduated from SIUC with an MA in Art History and Visual Culture. She curated the exhibit New Deal Art Now: Reframing the Artifacts of Diversity, at the University Museum.