If any two exhibitions underline the attenuation of radical politics in contemporary visual art it is the Museum of Modern Art’s “Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World” and MoMA’s PS1’s “Zero Tolerance.” The micro-aggressions against “good craft” in “Forever Now” hint, but only hint, that something is wrong in curator Laura Hoptmnan’s anti-teleological utopia. This is not Hoptman’s first anti-historical rodeo. Her fidelity to post-modern orthodoxy could be seen as early as the 1994 "Beyond Belief" survey of Central Eastern European art. Oddly enough, the assault on context is echoed in curator Klaus Biesenbach’s decision to exhibit almost everything in “Zero Tolerance,” a show that poses as the quintessential protest exhibition, as digital projection. By presenting ACT UP’s 1987 SILENCE=DEATH poster as a projection instead of an actual print, Biesenbach removes both the auric (distancing) power of the original artifact while simultaneously decontextualizing it from the historic struggle from which it was born. In “Zero Tolerance” we walk through a morass of protest images bombarding us a white noise; a dungeon of eternal struggle. In “Forever Now” we navigate the echoes of gestural abstraction, but without the defiant assertion of individual subjectivity that situated the New York School against post-war American consumerism.

The Atemporal Bourgeois

There are many factors involved in this mutual failure. Key among them is the intentional or inertial acceptance of living outside (or after) history. Laura Hoptman argues that contemporary painting exists in what amounts to a morally neutral smorgasbord of stylistic and conceptual options: “Time-based terms like progressive — and its opposite, reactionary… — are of little use to describe atemporal works of art.” She continues: “In this new economy of surplus historical references, the makers take what they wish to make their point or their painting without guilt, and equally important, without an agenda based on a received meaning of style.” Hoptman probably does describe, with some accuracy, the cultural condition of a privileged minority, situated at the center of global cities, in which the cultured can encounter the world as a tourist in space and time. The majority of the human race, however, interacts with space and time in a highly constrained manner (socially, economically, culturally). The proletarian figure experiences a gothic temporal displacement: constant reminders of autonomies gained and lost, of future and past threats to an already distorted subjectivity.

A second factor is the separation of art’s social and spiritual functions. Inheriting a misunderstood legacy from the distancing techniques of epic theater, situationist détournement, institutional critique and the “anti-art” gestures of the 20th century much political art aims to “expose mythology” rather than create it. The problem with this approach should be clear. Exposing the supposed lack of meaning behind the art gesture, in an art world that already disbelieves any such meaning (see Hoptman above), reinforces rather than challenges the status quo. Of course, for vulgar Marxists. this is a non-question. For the vulgar Marxist the spiritual dimension of art is a laughable bourgeois distraction from the struggle. In the meantime the spiritual realm of art, its fusion of art and philosophy, of hand and mind, is left to those who most despise the prophecy of working-class emancipation. Lately this has gone by many names: zombie formalism, new casualism, atemporal painting.

The problem is not merely the alienation of a human realm against itself. That is the normal condition of capitalist culture. The problem is that this separation weakens the spiritual function of art by separating it from its context (we hear the prayer of Jesus on the mountain but not the footsteps of the Romans coming to arrest him), while at the same time weakening the social role of art (we see the chains but not the complex historical subjectivities of the imprisoned). This explains what is wrong with the utter lack of the social in “Forever Now” and what is wrong with the (almost) total lack of the spiritual in “Zero Tolerance.” PS1’s depiction flattens the proletarian subject (in no small part by reducing that subject to its relationship with the coercive state). MoMA writes the proletarian subject out of the story altogether.

The detachment of “Zero Tolerance” from context is all the more startling in that the exhibition takes its name from New York City’s policing policies in the 1990s. As Julia Friedman writes:

What unfolds over at least seven rooms of the museum is an extremely wide range of locales, sociopolitical situations, and time periods, making for a problematic dispersal even as wall text explains the various contexts. For example ACT UP New York’s SILENCE=DEATH poster from 1987… shares a room with Pussy Riot’s ‘Punk Prayer-Mother of God, Chase Putin Away!...grouping artists together simply for their use of performance in social protest and a vaguely similar end goal destructively reduces the complexity of both.

Similarly a projection of a poster by John Lennon and Yoko One is randomly placed near a projection of screen print by Joseph Bueys.

This ideological and aesthetic state of affairs is a product of historical processes rejected by Hoptman and ignored by Biesenbach. The vexing problems facing contemporary artists (and well meaning curators) are the albatross of the post-modern heritage. Post-modernism rejected both the essentialism of modernist art as well as totalizing political metanarratives (i.e. Marxism). Art was deprived of both primal experiential/gestural aspects (after all, in post-modernism you have no essence to express) as well as collective political demands (just take your place in the global market utopia).

It is quite probable that the ruling elites have actually come to think of themselves as existing outside of time and space; an atemporality that not only reflects an ideological position but the way the individual bourgeois moves through the current world. They are situated in the center of global cities where the whole world can be brought to their feet. They move freely to sample (however superficially) all that history and culture has bestowed upon them. Meanwhile, the great majority of the human race remains utterly constrained by time and space. When the proletarian moves he or she is usually compelled by material and social circumstances (to the cities to escape gender persecution, across borders to find work, to schools to climb up the social ladder, etc.). The majority cannot fully realize the freedom of globalized digital time and space.

Of course there are other issues, particularly structural ones, at play—and these are ultimately the material basis of the post-modern ideology and its progeny. But it is my assertion that, while recognizing these structural problems is very important (the class dynamics of the art market, the elitist tendencies of art institutions), our ability to change these things (as artists) is quite limited. Ultimately these problems cannot be solved within our work but only through social struggle (conceits of some social practice artists aside). The question here is what we can solve in terms of artistic production. The artificial separation of the social and spiritual in art—and the detaching of art from history and the proletarian subject—are (partly) solvable within our work.

The Legacy of 1968

The legacy of 1968 in visual art, like the legacy of that year in Marxist and anarchist politics, did not prepare us for the neoliberal and post-modern turns. The New Left turned to the industrial working-class as the agent of social change just as the industrial proletariat began to be liquidated (in the U.S. and eventually much of Western Europe). Because young workers were rebelling (in part) against the prospect of being trapped in mind-numbing blue-collar jobs, the end of the post-war corporatist era could appear, at an individual level, as both an economic crisis and/or something like freedom (few who managed to come home from Vietnam in one piece wanted to die in the stamping plant or the coalfields). In the U.S. this tendency was reinforced as inflation pushed significant numbers of blue-collar workers into higher tax brackets, providing a basis for conservative anti-tax rhetoric within the working-class. Likewise, the turn to the apparent multiple perspectives of post-modernism could seem liberating (particularly for people of color, queer and feminist voices, etc.) after the post-war consensus, even as that theory included, at its core, a deeply reactionary rejection of any sort of collective emancipation (including for people of color, queer and feminist voices). The contradictory libertarian and socialist impulses of 1968 were resolved, in certain key circles, in favor of the former.

The full extent of political artistic gestures emanating from the last great radicalization is beyond the scope of this article. The balance sheet is mixed—for every Gran Fury there is an esoteric (and yet somehow unpoetic) Critical Arts Ensemble, for every Feminist Art Project there is a paternalistic “social-practice” performance. What will be outlined here are some cul -de-sacs in oppositional or social art production that have held disproportionate influence; as well as some possible artists around whom to center a new genealogy for contemporary anti-capitalist art production.

Dematerialization in a Material World

Conceptualism (in the U.S.) was arguably the most immediate impact of the 1960s radicalization on “serious” visual art (leaving aside the question of a queer reading of Pop Art and the often ignored relationship of Civil Rights among African American artists). The impulse to define, as Lucy Lippard argues, and remove the art gesture from its circulation as a commodity, was bound up in the conceptual turn. Conceptual strategies allowed for a sort of formal democracy—a work of art could be, along with some very basic instructions or a score, sent anywhere at anytime. This foreshadowed, of course, the far more rapid circulation of information that was to come. At the same time, as Lippard notes, there was nothing populist (or popular) about conceptual art. Institutional critique pointed toward more didactic possibilities, albeit with its own problems, but the idea of escaping commodity status was conceptualism’s paramount claim to radicalism.

In a decomodified ‘idea-art,’ some of us (or was it just me?) thought we had in our hands the weapon that would transform the art world into a democratic institution.

Of course, as Lippard notes, the art world found a way to commodify conceptual gestures.

Even in 1969… I suspected that ‘the art world is probably going to be able to absorb conceptual art as another ‘movement’ and not pay too much attention to it…’ Three years later, the major conceptualists are selling work for substantial sum here and in Europe… Clearly, whatever minor revolutions in communication have been achieved by the process of dematerializing the object…, art and artists in a capitalist society remain luxuries.

Similarly, institutional critique could also turn inwards — particularly when moving from protest of the war, civil rights and anti-racism toward esoteric engagement with the art institution. The most important formation was the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC). The AWC did important work protesting the connections of museums to the war, drawing attention to the mistreatment of artists, and underrepresentation of artists of color. Later on organizations like Women Artists in Revolution (WAR) would challenge the systemic sexism of the art world. But as the movements of the 1960s and 1970s morphed into the brutal ground of the 1970s economic crisis, and as revolt became reaction, the art world rebellion fizzled out.

After three years of activity, the AWC wound down in 1971, along with the Vietnam War and the fragmentation of the 1960s rebellions. There were the usual splinters and wounds, but the art movement was a stepchild of the larger Movement, which had already crashed.

This (American) branch of conceptualism had a profound influence on art, even as its utopian (anti-commodification) gesture was quickly undermined. Much of that legacy is positive. However, it has also tended to be isolating, reinforcing a closeted art world: art’s separation from narrative subjects and more popular audiences — the stuff from which actual revolutions are made. As Lippard recalls, “only later was much attention paid to the ways artistic content itself was manipulated” by the elite institutions of the art world. The institution could never be changed by critique alone. The danger of conceptual art and institutional critique alike was that they could reinforce the idea that power was located in “discourse,” thereby depriving art of its ability to emote and valorize those social forces that can actually change the world of art.

The Society of the Spectacle(s)

The most important influence of “1968” on political art has been situationism; Guy Debord’s alternatively insightful and convoluted fusion of Dada, Surrealism, Marxism and media theory. Its two most important (and somewhat contradictory) ideas are détournement (detour) and dérive (drift). The latter can be read as an updating of André Breton’s (and to some extent Walter Benjamin’s) interpretation of Charles Baudelaire’s flaneur (idler). The flaneur wandered the streets of Paris, experiencing, due to a lack of utilitarian purpose, something like the truth of the city. For Breton and Benjamin this took on more radical implications. Their flaneur saw the ghosts of a thousand murdered Communards. For Debord, drift could be generalized into the spectacle of consumer capitalism, creating “genuine” experiences (in a Romantic vein alien to many of his future disciples) by taking a non-utilitarian approach to the chaos: “immediate participation in a passionate abundance of life” vs. “an ever more manipulative and oppressive consumer and media society.”

The former concept, detour, required a more conscious (less “automatic”) relationship to the spectacle: a conscious manipulation aiming to expose the truth hidden beneath it. This is situationism’s legacy in culture jamming, etc. (although it should be noted that this method was also employed by the Berlin Dadaists in 1919). In terms of art situationism is an interesting theory. As a guide to social struggle it is more problematic. Drift can produce interesting artwork; even good political artwork, but it does not live up to the hype of “political rupture.” Detour can, at times, contribute to political radicalization, or more often express it, but only in concert with existing social struggles that are governed by “cruder” logics (stopping service cuts, stopping wars, opposing rape culture, raising wages, etc.). Situationism’s legacy, therefore, is disproportionate to its historical importance and current value. Nevertheless, the original situationists remained faithful to the basic idea of working-class emancipation (calling for “workers councils” or soviets in the French May), while subsequent imitators have often abandoned the actuality of revolution, turning the academic variant of situationism into a sort of (dull) signification game. Sadie Plant argues (in a book published at the height of post modern craze):

The line of imaginative dissent to which Dada, surrealism, the situationists, and the activists of 1968 belong continually reappears in the poststructuralist and desiring philosophies of the 1970s, and the post-modern world view to which they have led is itself faced with the remnants of that tradition…

A cursory reading of poststructuralist thought leaves revolutionary theory without a leg to stand on.

...although poststructuralism is in some senses a radical break with the situationist project, a host of continuities makes it impossible to oppose the two world views completely. The interests, vocabulary and style of the situationists reappear in Lyotard’s railings against theory and Foucault’s maverick intellectualism…

“Like the situationists,” Plant argues, the poststructuralists “observe that the world now seems to be a decentered and aimless collection of images and appearances… and declare the apparent impossibility of future progress and historical foundation.” Without expression or revolution all that is left is the discursive trap. Art ceases to be art (it is merely more communication) and power ceases to be centered (it is all just an endless discussion). Far more interesting are those who continue to apply situationist ideas outside of the academic and gallery space, attempting to create actual disruptions, artists who “place their work into the heart of the political situation itself.” These “Interventionists,” as described by Nato Thompson use “tactics” that:

[C]an be thought of as a set of tools. Like a hammer, a glue gun, or a screwdriver, they are means for building and deconstructing a given situation. Interventionists are informed both by art and (more importantly) by a broad range of visual, spatial and cultural experiences. They are a motley assemblage of methods for bringing political issue to an audience outside the insular art world’s doors.

The cultivation of an audience beyond an insular art world is to be lauded. There are, however, two problems with the interventionist model. It tends to devalue the artist as artist (constructor of mythologies) while overly privileging the artist politically. Equally important is the utilitarian language used to describe such art. If such art is just a “tool” the social movement should democratically control it. If it is “subjective expression” (in some not quite definable aesthetic sense) it can serve the movement, but only by being art and allowing the movement to determine its own strategies and tactics. The artist(s) can (and should) show up on the march or the picket line as individuals of equal standing. The other protesters can (and should) view and discuss art. Blurring the two, however, serves neither. It feeds the comforting lie that “everyone in this society is an artist” (when this society is designed to ensure that is not the case) as well as the lie that to be an activist one must be some sort of expert (when, in fact, the opposite is the case: those best positioned to fight are those impacted most directly by the injustices of the system).

Artificial Hell

“Social practice” art appears to offer an alternative; but as Claire Bishop points out, one of the main problems with (much) social practice art is its rejection of authorship (in theory). This is a seemingly radical gesture that is in actuality inherently conservative. Leaving aside concerns about paternalism, the rejection of the author in the context of mixed consciousness means ratifying the ruling ideas of society (which includes rejecting actual social struggle). “[C]ompassionate identification with the other is typical of the discourse around participatory art,” Bishop argues, “in which an ethics of interpersonal interaction comes to prevail over a politics of social justice.”

In insisting on consensual dialogue, sensitivity to difference risks becoming a new kind of repressive norm — one in which artistic strategies of disruption, intervention or over-identification are immediately ruled out as ‘unethical’ because all forms of authorship are equated with authority and indicted as totalizing.

Empathy is an extremely useful tool for the artist. Art is an empathetic project. But even when one understands the rationale of the Kingpin (as he tries to gentrify Hell’s Kitchen) the only truly human response is to side with Daredevil. This requires judgment, including aesthetic judgment. “[T]he aesthetic doesn’t need to be sacrificed at the alter of social change,” Bishop writes summarizing Jacques Rancière, “because it always already contains that ameliorative promise.” In other words, the promise of genuine liberation is not that all voices are equal but that all voices can become equal; can master their own subjective expression.

In our collective Western consciousness, and probably our unconscious as well, we do not have images of artists as socially concerned citizens of the world, people who could serve as leaders and help society determine, through insights and wisdom, its desirable political course.

This bold statement can only be considered remotely accurate if one ignores the history of Marxist and anarchist playwrights (Brecht, Fo, Badiou), anti-capitalist art movements (Mexican muralists, Berlin Dada, Surrealism, Constructivism, Arte Povera, Situationismm etc.), socialist poets (Mayakovsky, Brecht, Neruda) and socialist filmmakers (Eisenstein, Godard, etc.). This willful ahistoricism makes sense when one considers the other problem with the above statement by Carol Becker: its elitism. At the end of the day the socialist and anarchist art traditions held that it was mass social movements that made change. Becker’s version of social practice art privileges the artist over the community.

This is not to say a kind of “social practice” art is not possible, when approached in the proper way, as in Joseph Beuys’ “social sculpture.” Interestingly it is the very aspects of Beuys’ practice that led Benjamin Buchloh to call Joseph Beuys a fascist that set his work above most contemporary social practice. The narratives and myths associated with Beuys allowed him to conduct social practice art as art. Beuys did not pretend to be neutral or a professional activist. Beuys pretended to be a shaman. His most practical acts (the formation of the Green Party, the Free University) did not blur the lines between art and radical politics but reinforced the value of both. A similar approach, without the personal mythmaking, can be seen in his artistic progeny — from Doris Salcedo to Chicago-based Amie Sell. The narratives (of the victims of war or of displaced working-class communities) are front and center, but so is the particular narrative and aesthetic of the artist. The mythology constructed by Beuys, or the practice of Sell and Salcedo, create Brechtian distance.

Art as Epic Theater

The ultimate problem with denotative conceptualism, post-Marxist situationism and social practice art is their tendency toward atemporality and hostility to narrative and metanarrative. A 21st century anti-capitalist visual art, therefore, approaches the art space as a theater and the art gesture as narrative. It acknowledges that, in this society, art remains a rarefied occupation. It also asserts that the central actors in social transformation are not artists but the exploited and oppressed. A 21st century anti-capitalist visual art does not preclude conceptual, situationist or social practice concerns. It believes that the goal of such art is to enable a new oppositional (and eventually socialist) mythology to be born—an art that (in as much as it can) enables conscious proletarian subjectivity. The theater, of all the ephemeral and non-mechanical arts, provides the greatest fusion of pathos and politics. The theater is, in its origins, both State (the first imperial and city-states) and church (the ancient rites). As Alain Badiou writes:

…Politics takes place, from time to time. It begins, it ends. And, similarly… it follows (and this is an essential triviality) that a theatrical spectacle begins and ends. Representation takes place. It is a circumscribed event. There can be no permanent theatre… everything in it, or almost everything, is mortal.

And so it was theater that witnessed the greatest expression of Marxist aesthetic thought in the 20th century — in the form of Bertholt Brecht’s epic theater.

Epic theatre is a product of a historical imagination. Brecht’s ‘plagiarism,’ his rewriting of Shakespeare and Marlowe, are experiments in whether a historical event and its literary treatment might be made to turn out differently or at least be viewed differently, if the processes of history are revalued. Brecht’s drama is a deliberate unseating of the supremacy of tragedy and tragic inevitability. Echoing his own "Theses on the Philosophy of History," [Walter] Benjamin comments: "It can happen this way, but it can also happen quite a different way — that is the fundamental attitude of one who writes for epic theatre."

Brecht sought to engage the audience, appealing to the traditional emotional and visual snares of the dramatic arts, while alternatively “distancing” the audience from those tropes. The goal was to shake off the mixed-consciousness of capital and spur a proletarian audience into action, towards social revolution. The conditions of Weimer Germany, of course, are different than the conditions of today. We do not have mass socialist (genuinely socialist) and communist (genuinely communist) political parties. The working-class is far less organized. The right-wing threat is real but it is not cohered in an organized mass fascist organization, etc. Neoliberal capital functions quite differently (but not fundamentally so) from laissez faire capital or Depression-era corporatism, etc. Regardless, Brecht’s distancing techniques aimed to “disrupt the suspension of disbelief” inherent in the theater. This paralleled the need to disrupt the belief in the bourgeois state, reformism, German nationalism, the church, etc. in the mind of the proletarian audience. Today, disbelief reigns supreme in the art world (in part as a bulwark against “totalizing metanarratives” like socialism). To interrupt this disbelief we need to employ a similar Brechtian alternation between distancing and distance eliminating tropes. An electric shock can both stop and start a human heart. Distance can expose the truth of labor inherent within a simulation, but it also creates “auric” value, allowing a cultural sign to take on “spiritual” weight (the subjectivity of the person behind labor); valorizing the temporal “metanarratives” the Hoptmans of the art world want so badly to bury.

At the same time a theatrical approach to contemporary art allows the assertion of the proletarian narrative (the constrained subjectivity). This does not mean that the “characters” of the new art need be proletarian in the classic sense (although many should be). It means they are conditioned by their very temporal interactions with the material and social world. Their existence denies the false estrangement with time of “Forever Now” and asserts that the possibility of emancipation remains. This raises, once again, the idea Benjamin noted in Epic Theater: It can happen a different way. The new art, as a kind of theater, can begin to raise the prospect of a revolutionary imagination.

The artists discussed below do not perfectly fulfill the above, but will touch on (at least some) of the following:

1) The art space as a theatrical space and the art gesture as a narrative; as opposed to the art space as neutral site of the cannon or as irredeemably compromised. The assertion of the theater re-connects art to its ancient political and spiritual roots. Or, as Claire Bishop notes of certain strands of installation art, it engages the viewer as a “literal presence.”

2) The presentation of narrative (the constrained subject) and metanarrative (the actuality of emancipation, freedom, etc.); as opposed to the weak essentialism of zombie formalism, the condescending philanthropy of much social-practice art or the superficial radicalism of pyrrhic gestures (seemingly radical interventions, some street art, etc.)

3) The use of a distancing method (creating auric value) to interrupt disbelief, borrowing on Walter Benjamin and Bertholt Brecht; the use of “traditional art making” and other tools to valorize the spiritual subjectivity of the proletarian subject; opposed to the false belief that political art is opposed to the construction of mythology. It is interesting to note that, as Julia Friedman does, the “strongest works” in “Forever Now” are not the video projections but rather Rikrit Tiravanija’s Demonstration Drawings that feature “200 works commissioned and collected by Tiravanja in response to protest of Thailand’s 2009 military coup.”

The final two concerns are more prognostic than evaluative:

4) The cultivation of audiences beyond the art world(s); an audience for contemporary visual art that exists beyond the audiences of the isolated academic avant garde, the rarefied art market, or small circles of culture jammers, etc.

5) The possibility of presenting a differentiated totality; that the complex, unique but conditioned subjectivities of the working-class can combine; that the proletarian mass is not homogenous but neither is it inherently atomized (see Occupy, the Arab Spring). Tiravanija’s Demonstration Drawings can serve again as a counter-model to the rest of “Zero Tolerance”: “The variety of style, the delicacy of many of the drawings, the sheer number of works, and the poignant human expressions they capture make Demonstration Drawings an immersive, emotional experience.”

Emory Douglas: Expressionist Agit-Prop

In the mid 1960s Emory Douglas was making props for Black Communications Project in the Bay Area — a theater collective that included the poet Amiri Baraka. Douglas produced a series of “flats” that could be easily moved and changed between acts or plays, developing what Baraka would describe as an “expressionist agit-prop.” In 1967 Douglas joined the nascent Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BBP), eventually becoming its Minister of Culture, devoting his artistic skills for the next decade to the party. Douglas would design or supervise much of the art in the Black Panther (the BPP’s newspaper) and would introduce a weekly poster to be printed along with the newspaper. These images tended to fuse hand-made drawings, often with heavy black lines reminiscent of some African designs, caricatures that recalled George Grosz, along with Constructivist and John Heartfield-like photo-collages. This combination of mechanically reproduced images with subjective hand-made expressionism mimicked the distancing techniques of Epic Theater. The stories Douglas told were the heroic BPP battles with racism, war, capitalism and the police, as well as the stories of “regular” African Americans’ everyday lives. There was both collective struggle and subjective personality—whether it was that of Douglas, a single mother, the grotesque subjectivity of the “pigs.”

Douglas did not merely aim to make propaganda (although he made excellent propaganda). He (along with the BPP) aimed to construct a counter-mythology, to “fuse everyday Black life with a revolutionary spirit.”

As Laura Mulvey argues in her essay, "Myth, Narrative, and Historical Experience," "moving from oppression and its mythologies to a stance of self-definition is a difficult process and requires people with social grievances to construct a long chain of counter myths and symbols."

With the passage of time, the older work of Douglas has taken on an ephemeral and gothic character. The newspapers and posters designed by Douglas have become, in part, indexical records of the political performance of the BPP, a second layer of auric distancing. The recuperation of Douglas by the art world has given him the chance to preserve the memory of the BPP in a new arena, and his past work has often been presented (rightly) in a theatrical manner. The inclusion of Douglas in the art space is an opportunity — not just for Douglas (although this recognition is well deserved), but an opportunity to change the nature of the art space itself.

William Kentridge: Double Performances

South African artist William Kentridge also got his start in agit-prop theater. Kentridge, however, became ambivalent about the project and its ability to communicate the depth of the alienation and suffering he witnessed:

We would stage a play which showed domestic workers how badly they were being treated, implying that they should strike for equal rights. This would be presented in a hall with four thousand domestic workers…There was a false assumption about the public, in that we ‘knew’ what ‘the people’ needed, so I stopped my involvement with these groups. The early twentieth-century German Expressionists, such as Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, as well as the early Soviet filmmakers and designers of propaganda posters, had a way of using their anger, drawing it quite directly, that corresponded to what I was feeling at the time.

Kentridge’s work has been shaped by his position as a witness to apartheid — the white Jewish child of anti-apartheid attorneys — who could escape the direct barbarity inflicted on Black South Africans. Contemporary 1960s and 1970s American and European art did not “translate” to South African conditions. His work became shaped by his experience with theater (on the one hand) and inter-war European expressionism and propaganda on the other—allowing him to assert a human subjectivity in an inhuman context:

Adorno’s much-quoted proclamation about the end of lyric poetry [following the Holocaust] was directly followed by his assertion that literature must resist this verdict.

Black South African artist Dumile Feni Mhlaba (“Goya of the Townships”) also influenced Kentridge’s move toward neo-expressionism. Mhlaba’s work combined African motifs, expressionism and gothic naturalism.

In 1979, after years of struggling with painting, Kentridge produced a series of monoprints, fusing drawing and the theatrical. The series, Pit, created a small mise-en-scene. Sometime later Kentridge began his “signature” works of drawings turned into film animations; animations in which you can see the residual marks of previous iterations of drawing. These works were based around a series of fictional characters: Soho Eckstein (a white, presumably Jewish, South African businessman), Felix Teitlebaum (a white, presumably Jewish, South African artist) and Mrs. Eckstein (Soho’s wife and Felix’s lover). All around these characters the struggles of South African apartheid and the early 1990s transition unfold. The residual marks of the drawing serve as a Brechtian device for Kentridge:

The principle is that there’s a double performance: you watch the actor and the puppet together. The process recalls Brechtian theatre: the actors focus on the puppets and the audience has a circular trajectory of vision from the puppets to the actors and back to itself. It’s about the unwilling suspension of disbelief. In spite of knowing that the puppet is a piece of wood operated by an actor, you find yourself ascribing agency to it.

Felix in Exile (1994) captures Felix Teitlebaum, Kentridge’s sensitive alter-ego, in exile from South Africa on the eve of the first open elections. In a small one-room apartment Felix is surrounded by drawings and images of a Black African woman, Nandi surveys the violence of the Apartheid state (prefiguring the Truth and Reconciliation commission). Echoing previous films in the series, such as Mine (1991 — in which strikers miners confront the gluttony of Soho Eckstein, among other things), the film portrays a resigned complicity in which white South Africans witness the unraveling of the apartheid regime—resigned, in part, because of the compromise that allowed the economic order to survive the transition. Formalism and conceptual detachment were, obviously, not an option in the South African context, and while agit-prop was needed, something else was needed as well: an expressionist valorization of repressed subjectivities (of Black but also white South Africans).

Nedko Solakov: Top Secret

While conceptual art in the “West” (particularly the United States) tended to focus on the definition of signs (and was therefore preoccupied with text), conceptual art in the Stalinist Eastern Block tended to focus on story and narrative. Eastern European conceptual art echoed Moscow conceptualism in this regard. As I have written elsewhere:

Conceptual art in Moscow came into being in a different and totalitarian context. It drew on Russian and Soviet literary traditions. It therefore developed a far stronger narrative aspect, within and against the dominant narratives of Soviet life. If conceptualism in the West was driven toward categorization and definition, Moscow conceptualism was driven by a sort of “graphomania” (a compulsion to write). The targets of Moscow conceptualism were not the market or the commodification of culture, rather, as Boris Groys argues, the “rules of the symbolic economy that governed the Soviet Union in general.” This narrative conceptualism was connected to the way “normal” life functioned in the USSR. As Ilya Kabakov recalls, “[l]ife consisted of two layers, each person was a schizophrenic. Any person — a factory worker, intellectual, artist — had a split personality.”

Bulgarian artist Nedko Solakov made this double-life the subject of his autobiographical/confessional installation/sculpture Top Secret (1989-90):

The chest-file contains in alphabetical order notes with texts, drawings, and small objects that tell about the life of the author and about the period between 1976 and 1983, when, as a student who believed in Socialism, he collaborated with the secret service of the former political regime in Bulgaria.

In most former Stalinist states the records of the secret police have been (at least partially) made public. Bulgaria is an exception so there is little verifiable information about the extent of Solakov’s collaboration. Regardless, his confession produced a great deal of controversy. Putting aside, for a moment, the very real questions about Solakov’s complicity in a totalitarian state capitalist regime, what is most striking is the translation of crude oppressive state data into subjectivities; a restoration of what was lost (symbolically). The victims of the secret police are given the dramatic value of the drawings, hand-made, individual, subjective and expressive.

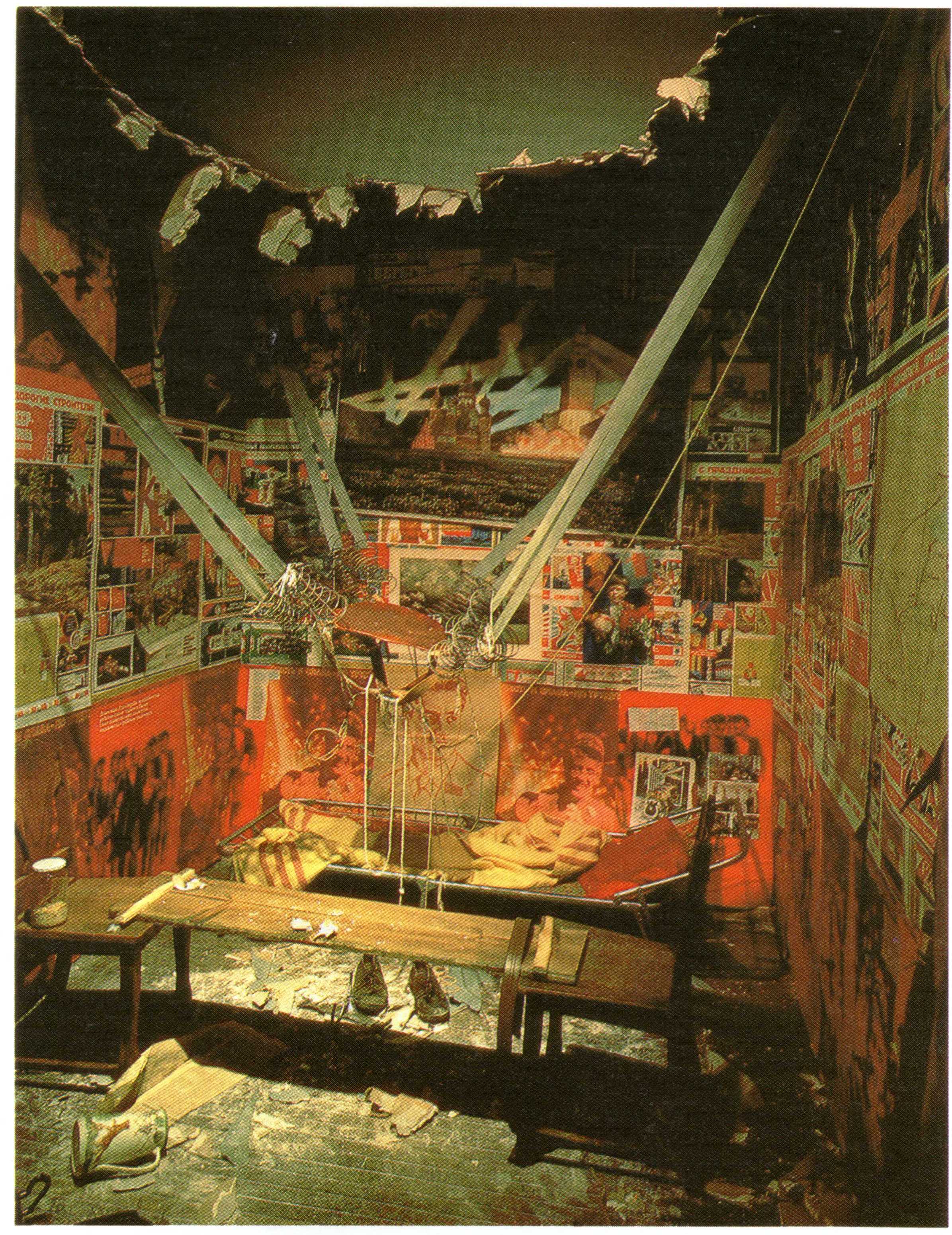

Ilya Kabakov: Total Installation

It is necessary to acknowledge Ilya Kabakov and his idea (along with co-thinker Bros Groys) of “Total Installation.” Kabakov’s origins were in the underground Moscow conceptual movement. As such his first international works (after the fall) tended to invert the symbolic mythology of the USSR towards the individual dreams of working-class or other socially constrained protagonists and archetypal figures of Soviet life. As Boris Groys described The Man Who Flew Into Space from His Apartment:

[I]n his installation uses images of Red Square and other symbols of the communist, Soviet utopia in order to tell the story of the individual, private fate of the hero of the installation. The great utopian narrative describing how all of humanity would one day be collectively propelled out of the gravitational pull of oppression and misery and into the cosmos of a new, free, weightless life has often enough been dismissed as passé, old-hat, a thing of the past. Yet stories of personal, private dreams and of individual attempts to realize these dreams cannot be told other than with recourses to that good old collective utopian narrative.

Of course, the ultimate reason that the story of individual emancipation cannot be told without the “good old collective utopian narrative” is because individual emancipation is bound up with collective liberation. The false socialism of the USSR concealed the truth that real democratic socialism from below was the alternative to both Western capitalism and Eastern “communism.” Regardless, Kabakov developed a series of strategies in “Total Installation” to allow for the suspension of disbelief in modern and pre-modern “utopian dreams.” In other words, “Total Installation” aimed to create a space in which metanarratives could be believed. In part this was done by creating a fictive space representing “the world” that contained within it expressive art objects. For Kabakov this has often been Cezannist paintings. Cezannism was an unofficial underground painting style (which mimicked the work of Cezanne) popular among a small layer of dissident artists before the rise of Moscow Conceptualism. As Claire Bishop argues: “An installation of art is secondary in importance to the individual works it contains, while in a work of installation art, the space, and the ensemble of elements within it, are regarded in their entirety as a singular entity.”

“Total Installation” combines three key aesthetic strategies: Brechitan alternation, presentation of metanarrative and combination of a differentiated totality (the carnivalesque). This parallels the contradiction between the hand and collage in Douglas, the residual traces of mark-making in Kentridge and the contradiction between the “official file” and the informal drawings of Solakov in Top Secret.

More of the Family Tree

There are many more possible strands from which to rebuild this kind of contemporary anti-capitalist art practice. This is an incomplete accounting of tasks:

- Revisit the great anti-capitalist art movements of the early 20th century with an eye toward how they created a dynamic relationship between the social and spiritual: Berlin Dada, Constructivism, Surrealism, aspects of German expressionism, etc.

- Revisit a Queer reading of 1960s Pop Art: This is a means of reconciling the populist gesture of 1960s art with radical political possibilities.

- Revisit the work of artists such as Doris Salcedo, Kerry James Marshall, aspects of work by Mel Chin, Kara Walker, Cindy Sherman, Allan Sekula, etc.

- Revisit the fusion of social practice and mythology ("irrational" social narrative) in Joseph Beuys' Social Sculpture.

And beyond the narrow visual "art world" we should be looking at:

- The traditions of radical theater and film: Bertholt Brehct, Dario Fo, Jean Luc Godard, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Luis Buñuel, etc.

- EC Comics and similar echoes of the Popular Front. EC comics (in the 1940s and early 1950s) provided a gothic naturalist influence in American speculative fiction and film.

- The avenging crowds of Emile Zola.

- The carnivalesque and grotesque as described by Mikhail Bakhtin.

- Gothic Marxism as discussed by Margaret Cohen and others.

- Progressive strands of contemporary speculative fiction, including but not limited to the work of Marxist authors such as China Miéville.

- The assertion of a gothic temporality in the novels of Phillip K. Dick.

- The expressive (subjectivity ratifying) aspects of Hip Hop and Punk (in their heydays or the contemporary undergrounds that remain), early zine culture, etc.

- The alternative drafts of history written by figures such as Sam Greenlee (The Spook Who Sat by the Door) and Lizzie Borden (Born in Flames).

“The Immortality of Things”

The fight to recast the art space as a theater, and art as narrative, will not be an easy one. Some art historians and curators have a vested interested in maintaining the weak echo of modernist essentialism. As the priests of art they are the keepers of the “word.” The art market, despite being dominated by the mega-galleries, contains many decent gallery owners. Regardless, the system depends on the sale of work. This commodification does not change the fact of the gallery’s theatricality but undermines its conscious use; weakening both art and the social and existential “truths” it aims to speak to. The gallery is the site of the conflict between art's use and exchange value. In the museum the art has supposedly arrived in its high temple. But, as Groys notes, “the museum is, by definition, opposed to progress for it is the place dedicated to the immortality of things.” Our goal, however, is not to stop the museum’s dedication to immortality, but to replace the word “things” with “people:” the billions of unique subjectivities repressed by the global anti-narrative of neoliberal capital. This includes the artistic fetish in as much as it is a record of the (very temporal) human performance.

Click for larger image.

Zero Tolerance: digital projection of ACT UP New York, SILENCE=DEATH (1987)

Oscar Murillo, “6. 2012-14,” (oil, oil stick, dirt, graphite, and thread on linen and canvas).

Cover of the 1994 exhibition catalog.

Zero Tolerance:Pprojection of Joseph Beuys' Democracy is Merry

Forever Now: Josh Smith's Untitleds (200-2013)

Zero Tolerance: Huran Farocki and Adrei Ujica, Videograms of a Revolution (1992)

Forever Now

Jean-Pierre Rey, [Girl waving flag in crowd during general strike, Paris], May 1968

Baltimore "Riots" of 1968

The Prague Spring, 1968

Unemployment line, New York City, 1974

AWC poster, “And babies,” 1970, poster, offset lithograph, printed in color, by Ronald L. Haeberle and Peter Brandt, Art Workers' Coalition

Hans Haacke, MoMA-Poll, 1970

Fred Wilson, Mining the Museum (1992-93)

Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle , still (1973)

Guy Debord and associates.

The Critical Arts Ensemble: Watching plants grow (literally)

Documentary on The Yes Men.

LA Rebellion, 1992

Subcomandante Marcos of the EZLN

The 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle.

Wilson Fisk ("The Kingpin") buying some art in the new Daredevil (Netflix).

Brecht's The Threepenny Opera.

Dario Fo's Accidental Death of An Anarchist

Diego Rivera's murals at the National Palace, Mexico City

Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Alain Badiou

Bertolt Brecht

Joseph Beuys

Amie Sell, Grace Church (2015)

Doris Salcedo, Untitled, Instanbul Biennale (2003)

Thomas Hirschhorn, Gramsci Monument (2013): A positive example of "Social Sculpture" as opposed to "Social Practice."

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled (no.. 138), 2006

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Demonstration Drawings at "Zero Tolerance"

Emory Douglas designs in The Black Panther

Emory Douglas, Black Panther poster (1974)

Emory Douglas installing/painting a poster recreation (2015)

Emory Douglas, Seize the Time, recreation of a 1971 poster in a Scotland gallery.

Dumile Feni Mhlaba (“Goya of the Townships”)

William Kentridge, Mine (1991), film still

William Kentridge, Felix in Exile (1994), film still

Nedko Solakov, Top Secret (1989-1990)

Nedko Solakov, Top Secret (1989-1990)

Nedko Solakov, Top Secret (1989-1990)

Ilya Kabakov, The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment (1989-1990)

Andy Warhol, Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr.' (1964)

Raymond Pettibone, Black Flag: Six Pack, album cover

Godard, La Chinoise (1967)

From EC Comics, "Judgement Day" (1953)

Bibliography

- Alain Badiou, Rhapsody for the Theatre (New York: Verso, 2013)

- Carol Becker, Surpassing the Spectacle: Global Transformations and the Changing Politics of Art (New York and Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2002)

- Walter Benjamin and Stanley Mitchell, Understanding Brecht (London: Verso, 1977)

- Claire Bishop, Installation Art: A Critical History (New York: Routledge, 2005)

- Benjamin Bucholh, “Twilight of the Idol,” in Claudia Mesch, ed, Joseph Beuys Reader (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007)

- Sharon Butler, “Abstract Painting: The New Casualists,” The Brooklyn Rail, June 3, 2011: http://www.brooklynrail.org/2011/06/artseen/abstract-painting-the-new-casualists

- Dan Cameron, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, J.M. Coetzee, William Kentridge (London and New York: Phaidon, 2010)

- Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Christy Lange, Iara Boubnova, Nedko Solakov: All in Order, with Exceptions (Hatje Cantz, 2011)

- Michael Corris, “Total Engagement: Moscow Conceptual Art: Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt,” Art Monthly Issue 319 (September, 2008)

- Jefferson Cowie, Stayin Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working-Class (New Press: New York, 2012)

- Ben Davis, “The Age of Semi-Post Postmodernism,” Artnet: http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/reviews/davis/semi-post-postmodernism5-15-10.asp

- Ben Davis, “What Occupy Wall Street Can Learn from the Situationists (A Cautionary Tale), ArtInfo (Oct 17, 2011): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/38868/what-occupy-wall-street-can-learn-from-the-situationists-a-cautionary-tale?page=2

- Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (Black and Red Press, 2001)

- Sam Durant, Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas (New York: Rizzoli, 2007)

- Julia Friedman, “A Simplistic Survey of Protest Art,” Hyperallergic (March 18, 2015): https://hyperallergic.com/188937/a-simplistic-survey-of-protest-art/

- Boris Groys, Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment (London: Afterall, 2006)

- Laura Hoptman, The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World (New York: MOMA, 2014)

- Lucy Lippard, “Biting the Hand: Artists and Museums in New York Since 1969,” in Julie Ault, ed., Alternative Art New York 1965-1985 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002)

- Lucy Lippard, Six Years (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1997)

- Michael Lowy, Morning Star: Surrealism, Marxism, Anarchism, Situationism, Utopia (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010)

- Vladiya Mihaylova, “Nedko Solakov and the Rest of the World” Flash Art 43 January February 2010

- Kim Moody, Workers in a Lean World (London: Verso, 1997)

- Jan-Werner Muller, “What Did They Think They Were Doing?” in Vladimir Tismaneanu, ed., Promises of 1968: Crisis, Illusion and Utopia (Budapest and New York: Central European University Press, 2011)

- Sadie Plant, The Most Radical Gesture: The Situationist International in a Post Modern Age (London and New York: Routledge, 1992)

- Walter Robinson, “Flipping and the Rise of Zombie Formalism,” Art Space, April 3, 2014: http://www.artspace.com/magazine/contributors/the_rise_of_zombie_formalism

- Saskia Sassen, The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo (Princeton: Princeton, 2001)

- Amy Ingrid Schlegal, “The Kabakov Phenomenon,” Art Journal Vol. 58 No. 4 (Winter, 1999),

- Sharon Smith, Subterranean Fire: A History of Working-Class Radicalism in the United States (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005)

- Hannah Stamler, “Kleas Biesenbach on ‘Zero Tolerance,’” The Creators Project (November 19, 2014): http://thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/klaus-biesenbach-on-zero-tolerance

- Nato Thompson and Gregory Scholette, The Interventionists: User’s Manuel for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life (North Adams: Mass MOCA, 2004) 13[1] Thompson

- Adam Turl, “The Art Space as Epic Theater,” Red Wedge Magazine (April 26, 2015): http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/evicted-art-blog/the-art-space-as-epic-theater

- Adam Turl, “A Thousand Lost Words: Notes on Gothic Marxism,” Evicted Art Blog, originally posted on the old RedWedgeMagazine.com: http://evictedart.tumblr.com/post/90494060378/a-thousand-lost-worlds-notes-on-gothic-marxism

- Adam Turl, “Interrupting Disbelief: Narrative Conceptualism and Anti-Capitalist Studio Art,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 8, 2015: http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/essays/interrupting-disbelief-ilya-kabakov-narrative-conceptualism-and-anti-capitalist-studio-art?rq=kabakov#_ftn5

- Adam Turl and Amie Sell, “Art (as Social Organism) vs. Gentrification” Red Wedge Magazine, September 2, 2014: http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/interviews/art-as-social-organism-vs-gentrification?rq=social%20sculpture

- Anton Vidokle, “In Conversation with Ilya and Emilia Kabakov,” e-flux journal #40 (December, 2012)

Adam Turl is an artist, writer and socialist currently living in St. Louis, Missouri. He is an editor at Red Wedge and is an MFA candidate at the Sam Fox School of Art and Design at Washington University in St. Louis. He writes the "Evicted Art Blog" at Red Wedge and is a member of the November Network of Anti-Capitalist Studio and Visual Artists.