“Bankrobber,” the Clash’s standout non-album single from 1980, was produced by Jamaican reggae artist Mikey Dread. It was a special moment in the Clash’s discography because it eclipsed their previous tributes to the Jamaican sound by finally having the courage to work directly with the culture, specifically its musicians, through mutually consented radical inclusiveness. As a key member of the Black Jamaican community, Mikey Dread recognized the Clash as allies and invited them to participate directly in the culture of resistance cultivated by reggae instead of just honoring it through tributes.

“Police and Thieves” and “(White Man) in Hammersmith Palais”, both released three years earlier, were the Clash’s most prominent reggae experimentations up until “Bankrobber”, but had treated dub and reggae like religious relics to be worshiped from a safe distance with an almost holy reverence. The cultural and racial divides that separated middle-class English punk from Jamaican dub were intimidating and substantial. Records like “Police and Thieves” and “Hammersmith Palais” show an enormous amount of respect towards reggae, but since no representatives of Jamaican culture were part of the recording, they were nonetheless restricted by the figurative barbed wire fences of statehood. They were not able to achieve the revolutionary sound that radical inclusivity makes possible and the creation of an authentic global people’s music was still, at this point, not fulfilled.

“All religions,” states Bakunin in God and the State, “with their gods, their demigods, and their prophets, their messiahs and their saints, were created by the credulous fancy of men who had not attained the full development and full possession of their faculties.” Up until this point, the Clash, in simply giving tribute to Junior Murvin rather than working in solidarity with him not only passively upheld cultural and racial divisions created by capitalism and state-ism, but in the objectification and worship that a tribute necessarily generates, dehumanized their idol and in turn disempowered themselves. And although the Clash did invite Jamaican producer Lee “Scratch” Perry to produce the punk powerhouse single “Complete Control”, it would not be until “Bankrobber” that the Clash recorded reggae in solidarity with a reggae artist.

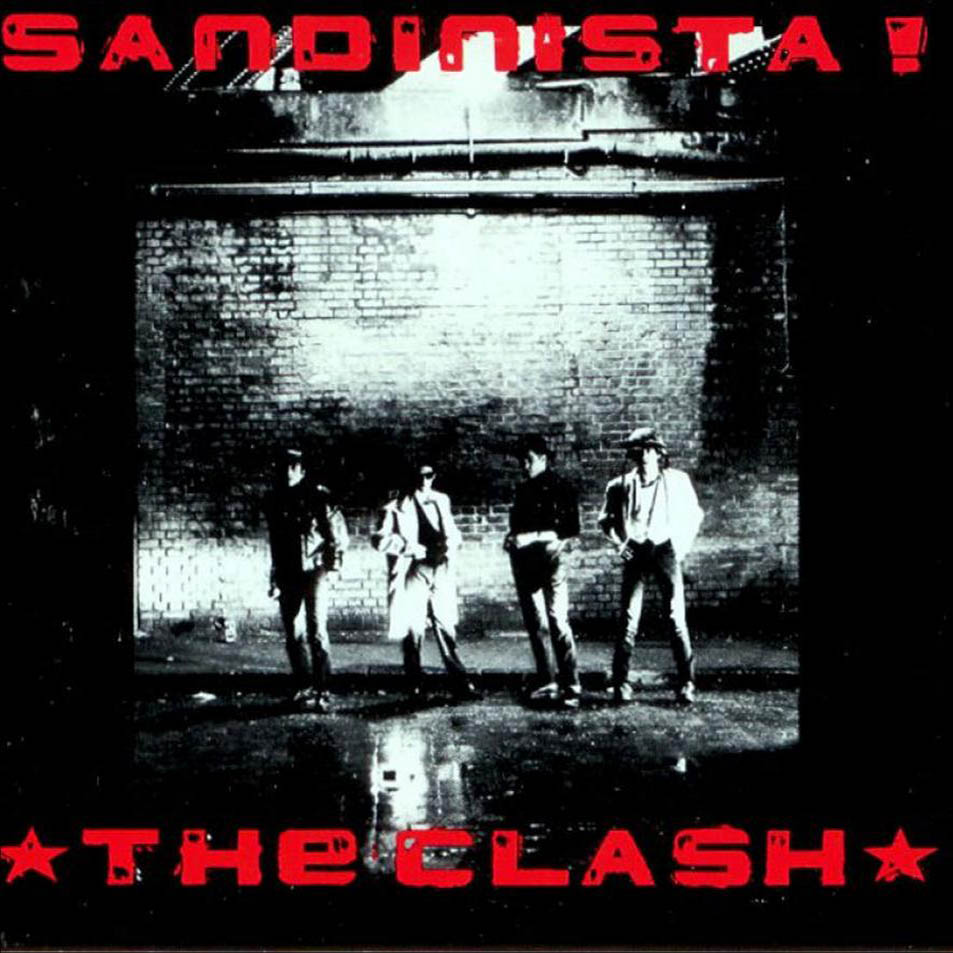

Thus “Bankrobber” marks the Clash’s moment of progress from living in the prison of religious objectification; seizing power of their creative process and moving forward in actively dismantling the capitalist concept of the non-white or the oppressed as “other.” In the act of destroying the “other” through artistic collaboration across state and cultural borders, the Clash had found themselves. They realized their own identity, as I believe we all can, via active solidarity and collaboration with the oppressed. This active solidarity is the logical conclusion and true fulfillment of the punk ethos, and what has made Sandinista! their greatest acheivement.

The template for revolutionary consciousness that the Clash set up in “Bankrobber” is one of the most important contributions to punk ever made. Punk, therefore, becomes fully realized when it no longer cares about fitting in with a prescribed punk sound, trend, or culture, but instead identifies all forms of folk or street music as reflections of self. The traditional targets of radical punk rage – politicians, greed, prisons, corruption, state violence, hierarchy, oppression – are shared by all forms of folk music.

In Sandinista! the Clash seems to ask, “Why not tear down the artificial walls that divide us and make music together?” In “Washington Bullets” for example, the Clash write:

Oh! Mama, Mama look there!

Your children are playing in that street again

Don’t you know what happened down there?

A youth of fourteen got shot down there

The cocaine guns of Jamdown Town

The killing clowns, the blood money men

Are shooting those Washington bullets again

As every cell in Chile will tell

The cries of the tortured men

Remember Allende, and the days before, Before the army came

Please remember Victor Jara,

In the Santiago Stadium,

Es verdad — those Washington Bullets again…

In 1977, those lyrics would have likely been accompanied by vicious, traditional punk instrumentation like that of “Complete Control” or “White Riot”. But on Sandinista! they were accompanied by marimbas and steel drums instead.

Sandinista! is filled with this determination towards radical solidarity; in fact, it is its central message. Hip-hop is paired with nursery rhyme radio pop; marimbas transition swiftly into celtic fiddles; gospel sets the stage for punk re-bakes of 1950’s rock n roll standards decrying the terror of the police state. This is the landscape of Sandinista!.

As a personal friend stated to me not too long ago, Sandinista! operates more as a switchboard than an “album” in the traditional sense. This may be the reason why it’s taken so long for Sandinista! to be appreciated as a classic like London Calling, which has become virtually unassailable, has. The simplest reason for this is that for all of its brilliance and all of its innovations, London Calling is still a conventional rock record. It is, as the phrase goes, “nothing but smashes”, delivering one brilliant track after another on a sixty minute locomotive of power.

In contrast, Sandinista! actively works to upend the ways in which music is sold and consumed under Western capitalism. Spanning three LPs and at almost two and a half hours in length, it’s almost impossible to take it all in in one sitting – and you’re not expected to. Sandinista! is not an album in the same sense that London Calling is: it is pirate radio. Sandinista! asserts itself as an environment, a playground, a street parade that you choose to enter and reenter from any angle. One you can leave when circumstances are right for exit. This manner of sound construction from the Clash allows Sandinista! to become a virtually inexhaustible listening experience.

There are, of course, the other awesome things about Sandinista! that make it so lovable. Most obviously the title is a reference to the Sandinista National Liberation Front in Nicaragua, and the album’s Columbia Records catalogue number is “FSLN1” for “Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional”. It’s the only Clash album to feature a lead vocal from every member of the group and the only one in which every member of the Clash is given equal writing credit. The band sacrificed royalties on the album in order to release a 3-LP package for the price normally given to a traditional one or two LP package. These are all instances where the Clash chose to discard capitalist norms of pop music profiteering to achieve the creation of a musical movement of intersectional global street music; to get those middle-class English white boys and girls to listen to Jamaican dub; to bury their beloved and famous punk sound so deep within six sides of vinyl that you have to wade through skiffle and disco to get there; to reclaim music itself as the sound of the people coming closer together.

Make it all folk music!

Now, is Sandinista! a perfect album? I think perfect is unproductive. God is perfect. But when we discard the notion of perfection as something to strive for, discard the desire for worship, and instead replace it with a genuine radically inclusive collaboration as the Clash did, that’s when we come closer to finding ourselves.

Dave Toropov is a writer and activist.