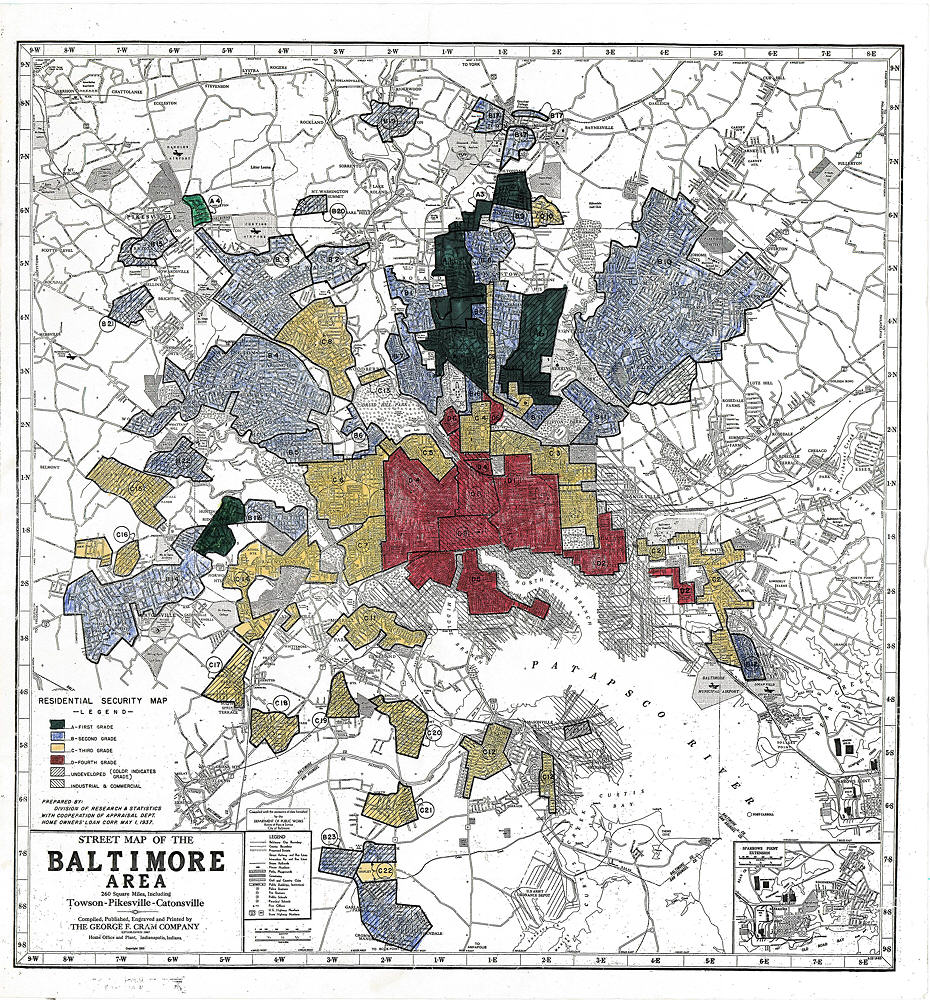

Redlining in Baltimore, circa 1930s.

When it was announced some months ago that the city of Baltimore would start cutting off the water of poor residents, the comparison became inevitable: Baltimore is the next Detroit. It was, and is, still a prescient parallel, a reminder that the devastation of America's one-time auto hub wasn't so much a cautionary outlier as a glimpse into the inevitable future of urban life. And, as with Detroit, it is impossible to disentangle the economic devastation of the city from the profound racism that is a daily feature of life in Maryland's largest city. It's for this reason that there is something to the claim, made by such writers as Ruth Wilson Gilmore, that the rebellion that has rocked Baltimore was as much a visceral outcry against austerity as it was a reaction to racist police violence. Malcolm's words "you cannot have capitalism without racism" ring true in this city, as they do in just about every American urban area. Yes, Baltimore is Detroit. It's also drastically different. In fact, the former's history may make it an even more accurate poster-child for the intersection of neoliberalism and American racism.

I never lived in Baltimore proper, but I did attend high school there (which is a story for another time). My experience of the city was certainly not like that of most residents. Even from my rather sheltered position, it was impossible to not notice the segregation, which was made strikingly literal at times. Neighborhoods like Guilford -- with its sprawling, immaculate lawns and the neoclassical homes that earned it a place on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001 -- are separated by physical walls from the boarded up buildings of Black, poverty-ridden Pen Lucy. My first protest in the city was in front of the Maryland Correctional Adjustment Center (now called the Chesapeake Detention Facility), a supermax prison where inmates were kept in their cells for 23 hours a day. It also housed the state's death chamber. This complex wasn't out in the sticks; it was (and is) located a mere stone's throw from Baltimore's Midtown area. Though I find myself convinced by radical writers who are now revisiting The Wire with fresh eyes and acknowledging its individualistic shortcomings, the fact remains that Baltimore's deep de facto apartheid and development as a late capitalist chemistry set made it a prime setting for compelling drama.

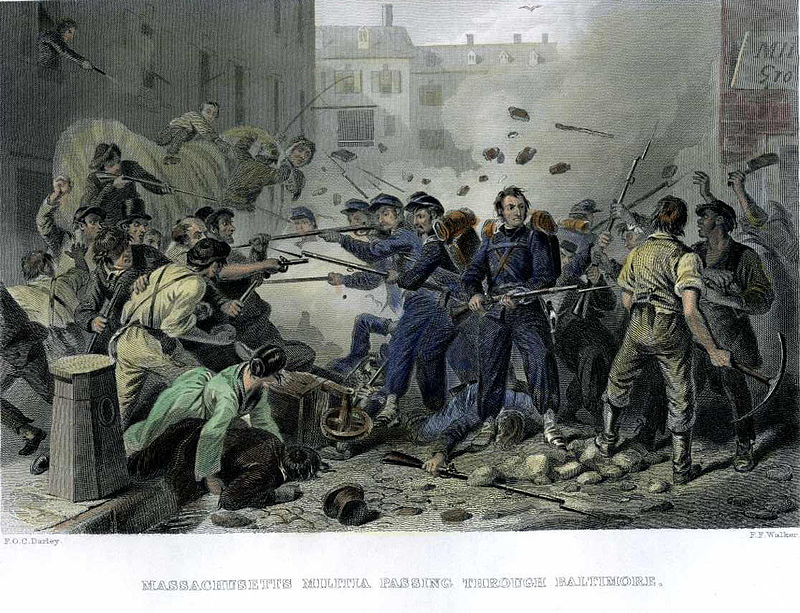

This is a city with a long history of holding tight to its racist past well after it's ceased to be practical even from the standpoint of capital. Long after the import of newly captured Africans was banned in the United States in the early 1800's, Baltimore remained a key port for interstate slave trade. During the 1850's, slavery ceased to be a profitable racket in the city, and yet it persisted as an institution. By the start of the Civil War Baltimore was home to the largest free Black population in the country, but also hosted one of the worst spates of pro-Confederate violence on Union soil in the early days of the war (an incident that killed four soldiers in the 6th Massachusetts Militia). As a "border state," the Emancipation Proclamation didn't apply to Maryland's slaves, even though its soldiers were officially on the side of the Union.

Pro-Confederate rioters attack the 6th Massachusetts in 1861.

To this day the state of Maryland can't seem to let go of its southern pretenses. "Maryland, My Maryland," the state's official song, was inspired by that aforementioned Baltimore massacre of 1861; the full version labels Lincoln a "tyrant," lionizes Marylander John Wilkes Booth, and even makes reference to "Northern scum."

In short Baltimore has long been, if you will, stuck in a kind of Yankee half-life, a place where the essence of the unfinished abolition of "the southern way of life" and the northern industrialists' haughty, elitist denial have uncomfortably rubbed up against each other. The city's history since the Civil War makes it look like any other northern town. Its railroads, shipping and factories have given it too industrial a character to be in line with the genteel agrarianism that distinguished the south into the 20th century. It was natural that the city be a major battleground during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and that it become a stronghold for organized labor up through the 1970's. "Operation Dixie" had no need to focus on Baltimore; the city was already a bastion for the Congress of Industrial Organizations by the end of World War II. Native-born Baltimore composer and pianist Eubie Blake's "hot ragtime" style was a major stepping stone in the development of jazz (a style that, appropriately, mirrored and signified the spread and evolution of the African American population), and the city was the site of important turning points in the careers of Cab Calloway and Billie Holiday.

The Great Migration and white flight have transformed it over the course of decades into a majority Black city, but you are frequently and distinctly reminded that the state surrounding it is below the Mason-Dixon line. Maryland enthusiastically embraced key aspects of Jim Crow -- particularly in the crucial industry of railroads. Between 1861 and 1933, 46 African Americans are reported to have been lynched, ten of them in the state's capital of Annapolis. The more rural and agricultural state has both stood in contrast to the city of Baltimore and provided a profoundly conservative check on the city's development.

Daniel Denvir quotes historian and Baltimore native Rhonda Y. Williams in his solid piece at CityLab, and the quote really captures the city's dueling souls: "Jim Crow existed in its southern ways and Jim Crow existed in its northern ways... We're a border city."

Or, as it was described by Helena Hicks, the African-American Morgan State student who sat in at Read's Drug Store in Baltimore five years before Greensboro: "If you came from New York, you had fewer rights than you ever had. If you came from North Carolina, you thought you'd made it North."

Though Maryland racism can carry with it a distinctly neo-Confederate flavor, the way in which it's been kept alive by urban development has been neither particularly northern nor southern. No surprise that the historic Black neighborhoods of Baltimore, which had been that way for perhaps a century or more, were the first to be redlined, the first to be uprooted and displaced by the building of the interstates, their refugees the first ones subject to predatory subprime lending. It would be impressive if it weren't so horrifying; Baltimore has managed to maintain a durable, flexible through-line of distinct segregation that has lasted since well before the Civil War.

* * *

One does not have to look for long to find a song about any US city's inequities, its violence and racism. Chalk it up to an essential feature of American cosmopolitanism. But it's not hard to see why Baltimore can provide such a dramatic setting, a city where America's ghosts at first seem completely out of place, but stubbornly manage to hang on. Bob Dylan's "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" comes off less a folk song than a calculated, theatrical condemnation (it was, after all, based on a Brecht-Weill composition). The ironic reference to the rich, murdering tobacco farmer William Zantzinger as a "noble" rather slyly relays the aristocratic airs that the Baltimore area's "old money" has always adopted, much like the south's old planter class.

By the time Nina Simone recorded her version of Randy Newman's "Baltimore," which has heavily made the rounds since events started popping off last week, there was a distinctly more widespread and heavy sense of desperation gripping the city. What had happened in the fifteen intervening years? In a word, neoliberalism. The economic crash of the early 70's never really bothered to leave most neighborhoods of color, and the more heavily industrialized a city was, the harder the white flight and outsourcing hit it. The sense of "heavy manners" that comes from the song's quasi-reggae sound was very appropriate.

The 1968 Baltimore rebellion.

Baltimore was drastically and quite tangibly reshaped in the aftermath of the riots that followed Martin Luther King's murder. Denvir's CityLab piece chronicles the way in which then-governor Spiro Agnew's response to the uprising -- a sharp pivot to the right -- was something of a prelude for the law and order rhetoric taken up by conservatives after out-and-out Jim Crow bigotry had become politically untenable.

This had a visual and aesthetic valence too, largely because law and order conservatism was so easily integrated into the deregulation, disinvestment, and the vast restructuring that allowed the bottom to drop out of poor and working class living standards. It's a common misconception that neoliberalism is essentially an extreme version of getting government out of business, when in fact there are countless realms in which a successfully implemented neoliberal project requires a robust state. Chief among these is law enforcement, which plays a particular and conscious role in keeping potential workforces pliant and communities spurned by austerity on the margins. And if all circles of daily life -- from government to culture -- are to be retooled for the maximization of profit, then it is only predictable that the city be literally reshaped by such a project, down to its very skyline. Architect and Maryland Institute College of Art professor Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson describes how urban planners deliberately shifted after those uprisings:

The architecture of cities changed after the 1960s. Here in Baltimore, we bricked over ground-level windows and turned our back on the street. Cultural institutions and universities hunkered inward. Public-facing front doors closed in favor of private, secure, bunker-like entrances. Baltimore wasn't alone. In cities across the country you saw an increase in concrete walls, barbed wire, berms, "bum-proof" benches, and soulless buildings that buffeted people from the street.

David Harvey's The Condition of Postmodernity has several references to Baltimore's shift from the 60's through the 80's in the book's chapter on postmodern architecture. Part of the significance here is that the book was published between the author's two stints at Johns Hopkins, but it's also true that the city provides some quintessential examples of the insidiousness of postmodern urban life. Billions have been spent on building what Harvey calls "managed and controlled urban spectacle," lavishly constructed projects intended to rise above the environment and emanate a sense of autonomous leisure, quite withdrawn from the realities of gentrification for a growing number of working people (particularly people of color) and the dilapidation that came part and parcel with it.

There are a couple acerbic ironies here. The first is probably the most obvious: that this spectacle, far from being truly autonomous of the urban devastation several blocks away, in fact is only possible because of it. The second is that such a philosophy inevitably backfires: the more brazen urban planners can be in denying the existence of the "other," the more likely it becomes that they start inadvertently flaunting the very disparity they were looking to paper over in the first place. How else can you place a massive prison smack in the middle of an urban area, then turn around and call it "Charm City" with a straight face?

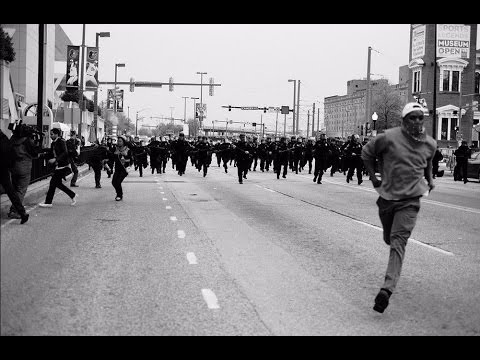

These are the metropolitan aesthetics of the New Jim Crow. They are not incidental, and they are not a bi-product. They spring organically from an urban vision that seeks to deny its own inequity by telling those left behind not only are they unwelcome, but that they don't exist. It has happened and continues to happen in every American city, exacerbating the persistent tensions of racism and exploitation that keep the system's motor running. But it is Baltimore, where the contradictions have always been particularly pointed, that has proven to be the powder keg. Almost fifty years after Dr. King's assassination, it has reintroduced urban rebellion not just to the realm of possibility but probability. The events in Ferguson were undeniably important, a spark for a movement that has recaptured the imagination of many. But Baltimore is where the spark really caught on, seizing a city a mere hour's drive from Washington, literally placing the fruit of America's brutality on the nation's doorstep.

* * *

The natural question now is: "what now?" The rebellion has subsided, the cops that killed Freddie Gray have been brought up on charges. The National Guard are pulling out of Baltimore, yet the New Jim Crow persists. The still-young Black Lives Matter movement has had the need for its existence confirmed once again. This piece isn't the place to hammer out concrete next steps. But it is worth returning to the subject of Detroit. Baltimore was, it is well known, far from the only city that saw unrest during the 1960's. There was Watts in Los Angeles, there was Harlem in New York, there was Rochester, there was Newark, Philly, Cleveland, Chicago and, of course, the rebellion that shook Detroit in 1967.

The Baltimore uprising.

Detroit was, in contrast to Baltimore, a quintessentially northern industrial city. The Great Migration had transformed its demographics in a way typical of the north. The car plants that had been a relatively steady source of employment (albeit one that was still rife with racism) for arriving southern Blacks had thus made it into a collision point that transformed American culture (particularly, in the case of Detroit, music). It's telling that demonstrators blasted "Dancing In the Street" from the rooftops during the rebellion. The song was, as Rollo Romig has cited, one that was greatly informed by the outlook of Berry Gordy, which “had been shaped by the principles I learned on the Lincoln-Mercury assembly line.” It was a "crossover" song, quality-controlled by Gordy to reach into the white mainstream. Playing it during a riot clearly communicated a sense the Black community wasn't just crossing over but taking over.

This uprising -- the largest in America during the 1960's -- wasn't just four days of mayhem and destruction. It was a key moment in the radical ferment among the city's Black population, a turning point from Civil Rights to Black Power. It was also, as such, a prelude to the foundation of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. Critics' insistence that riots can never be "productive" tend to miss this -- likely because they are terrified of the organizational implications of Black workers getting a taste of their own power. The same rhythms of industrial production that had shaped the city had, with the formation of the LRBW and DRUM, transformed into fertile fields for a resistance against racism and capitalism that was living in the heart of American industry.

Which brings us to contemporary Detroit. It is well known by now how the city's planners reacted to and regained traction from the rebellions of the 60's and the recession of the 70's. The Motor City's iteration of urban revanchism is notable in its extremity, but not in its essential character. Detroit has its Renaissance Center, Baltimore its Harbor Place. Detroit attempts to sell off its world-class art collection while boosting trendy new coffee shops, but Baltimore just wants us to "Believe."

Modern heavy industry, attracted as it is to a union-free workforce, has been finding its way back down south even as the Right-to-Work model is exported into the heartlands of the rustbelt. The transformation of work -- including the almost wholesale denial of it to key demographics -- has been dramatic; the unemployment rate in Freddie Gray's neighborhood is 51 percent. This, putting it mildly, places an obstacle in front of the rebellion's potential turn to the working class. But there's no getting round the fact that it must, which is partially why the walkout of west coast dockworkers in solidarity with Baltimore mattered so much. The same can be said for the involvement of the Black Youth Project and other anti-racist groups in April's Fight For 15 strikes. When the Black working class starts to move in the United States, it can be (and has been) explosive.

It is telling that the words of Tupac Shakur on urban rebellion have likewise made their way around the internet in the wake of Baltimore:

You have to be logical. You know? If I know that in this hotel room they have food every day, and I'm knocking on the door every day to eat, and they open the door, let me see the party, let me see them throwing salami all over, I mean, just throwing food around, but they're telling me there's no food. Every day, I'm standing outside trying to sing my way in: We are hungry, please let us in. We are hungry, please let us in. After about a week that song is gonna change to: We hungry, we need some food. After two, three weeks, it's like: Give me the food or I'm breaking down the door. After a year you're just like, I'm picking the lock, coming through the door blasting. It's like, you hungry, you reached your level. We asked ten years ago. We was asking with the Panthers. We was asking with them, the Civil Rights Movement. We was asking. Those people that asked are dead and in jail. So now what do you think we're gonna do? Ask?

The quote doesn't mention Baltimore directly, but it paints a very apt picture, and one that was just as relevant twenty years ago as it is today. And, as is now well-known, Shakur spent about two years of his life living in Baltimore; years that were both politically and artistically formative for him. And what he is describing here -- albeit crudely -- isn't too far from the "festival of the oppressed" atmosphere that revolutionaries are fond of invoking. It was also on display this past weekend when, after it was announced that six cops were to be charged in the death of Freddie Gray, protests continued. Yes, they were celebrations, and the mood of the participants was far more one of levity, but they were also acknowledging that the struggle is far from over. What's more, that feeling of empowerment that comes from taking back forbidden space doesn't fade easily. The right to the city is, after all, a right.