Let's put something aside here. There is a very legitimate and challenging debate among an admittedly small radical left regarding support for Bernie Sanders' run for the Democratic nomination. Anyone who says it's not challenging, or that the other side doesn't have serious arguments for or against, is frankly a liar and/or doesn’t take politics seriously. I am far less interested in Sanders himself or his campaign than what they represent.

And after his showing in Iowa last night, one has to say that what he represents is something very real and very powerful. Case in point:

Putting aside the very real nature of the Democratic Party as a graveyard of social movements, putting aside Sanders' shameful support for Israel's apartheid state and his shit stances on US imperialism, what he is delivering in this video is probably the most unapologetically leftist speech delivered by a major political candidate since Jesse Jackson ran for the nomination in the 1980s.

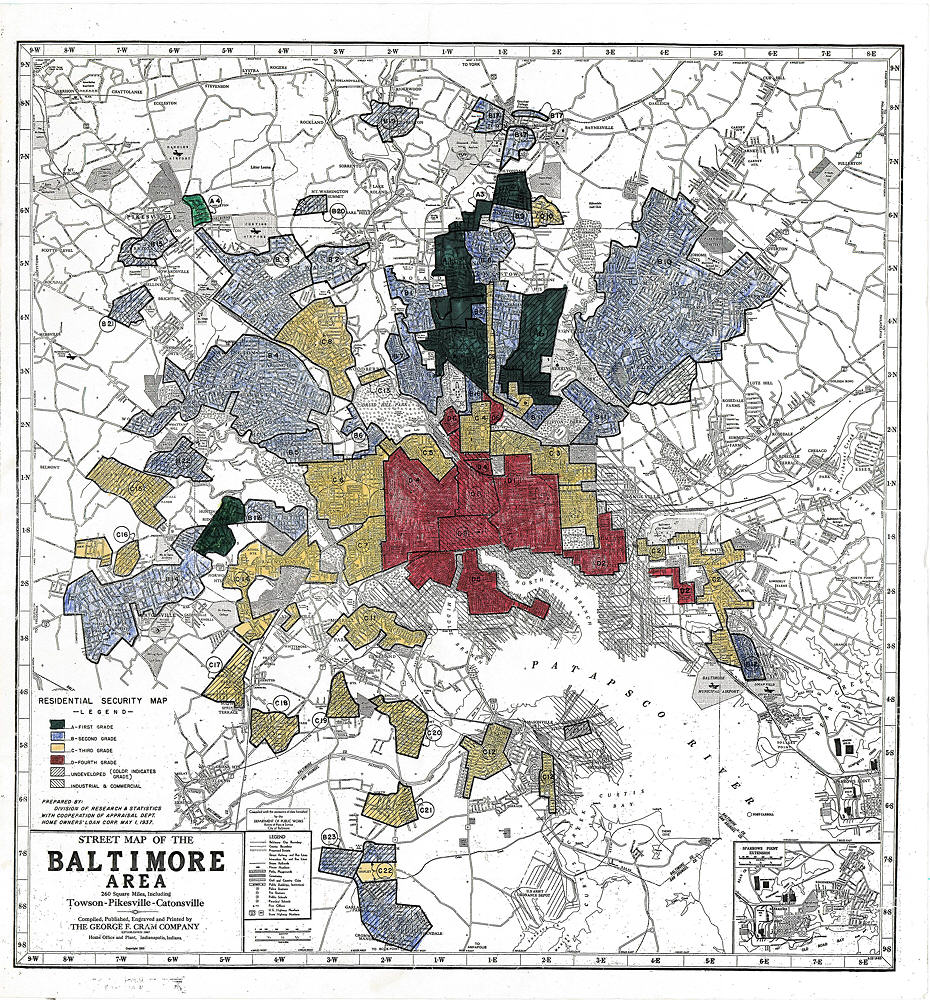

This goes well beyond the fact that Sanders identifies as a democratic socialist, or that a majority of Democrats in Iowa may identify as the same. Getting corporate money out of politics, taxing the rich, instituting a livable minimum wage, prison reform, universal healthcare, free education. These are basic old school social democratic demands. They are absolutely not revolutionary or anti-capitalist on their own but they are certainly a huge break from the neoliberal policies that have dominated the politics of the US for the past few decades. If the age demographic breakdowns coming out of Iowa are to be believed, then we are seeing a very concrete political expression of young people who have yet to see any recovery in their post-recession living standards.

One of the criticisms that some people shared with me regarding my latest piece on Donald Trump’s employment of aesthetics was that I didn’t use the opportunity to compare the “aesthetics of Trump” to what some called “the anti-aesthetics of Bernie.” After all, while the Donald has famously aestheticized himself to the point where he cannot even relinquish his obviously expensive toupee, Sanders doesn’t even to bother combing his hair. I didn’t want to take that up in the piece partially because “anti-aesthetics” are not actually a thing. Mostly because, for as much of a contrast the “look and feel” of #FeelTheBern may represent, it really is a small glimpse of the kind of revelatory aesthetics that pour out of a genuinely liberatory politics. And it is always a mistake to confuse a corner of the canvas with the full landscape.

Nonetheless, from a radical artistic and cultural perspective, there is undoubtedly something interesting and frankly exciting happening here. And it gives us an opportunity to discuss something that grabbed my attention and yours two months ago:

This speech is pure fire. No two ways about it. Killer Mike is dramatic, passionate, eloquent, and there is not an ounce of “acting” in it. There are a few poetic turns of phrase in there; just enough to remind you that he is indeed a wordsmith (and a ridiculously good one at that) but not so much that he’s relying on schtick. Compared to the high orchestration of most establishment political campaigns, there is a feeling of relinquished control in Mike’s words. And by throwing in a few well-meaning nudges aimed at how a preacher might invoke Dr. King to introduce Sanders, Mike even manages to cut briefly cut through a bit of the treacly, sanitized stereotypes normally trotted out when a major candidate wants to court “the Black vote.”

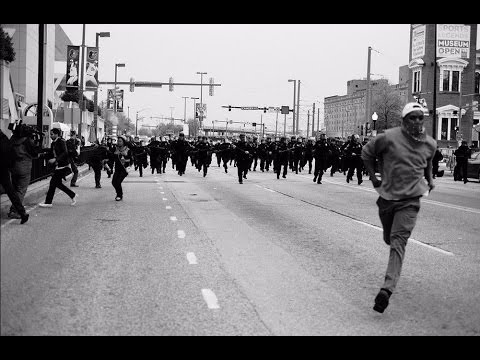

Again, let’s be frank. There have been grievances put forth by the Black Lives Matter movement against Sanders that deserve to be taken seriously, and these grievances in some ways reflect a very real limitation for American racism to be tackled solely through electoral means. The Sanders camp has attempted to rectify how it addresses these shortcomings, and it likely will have to keep working on this. But I would like to draw readers’ attention to the segment in this video where Killer Mike – who has over the past year emerged as one of the sharpest voices in rap openly allied with Black Lives Matter – takes on a newspaper critic. The critic who in particular “broke my heart” according to Killer Mike is the one who wrote “I don’t listen to rap music and after tonight I won’t be listening to Bernie Sanders.”

There is a word for someone who won’t listen to a political candidate because of their vague association with a genre that has emerged out of the struggles of people of color. That word is “racist.” That this particular racist has a major metropolitan newspaper willing to give him a platform speaks toward how necessary the Black Lives Matter movement is right now. The writer’s logic is very much in line with the kind of broad generalizations trotted out by Sarah Palin when she asserts that Common’s visit to the White House was akin to letting a thug or murderer through the front door. It has very little to do with the actual content of the music and far more to do with the racialized stereotypes that have always been painted across hip-hop with an over-broad brush.

For the Sanders camp to, in the midst of all this, still put Mike onstage to introduce Bernie reveals at the very least a willingness to publicly put itself at odds with a virulent strain of conservative, “color-blind racism” that lives very prominently in mainstream American culture. It is, in a weird and rather imperfect way, reminiscent of the broad support Obama received from rappers and other artists from the hip-hop community during his first campaign in 2008. That support was frequently apolitical in nature, but it also reflected America’s demographic shift and, in some very vague ways, discontent with the neglected state of the country’s disenfranchised majority. Obviously we know how that played out, but it doesn’t take away from the fact that there was something real being expressed in the midst of the electoral dog-and-pony show.

Now, in 2016, the contradictions are sharper, but so are the possibilities of where things can go from here. What Sanders and Killer Mike are putting forth in terms of image is not exactly grassroots or bottom-up aesthetics. Insofar as they are the “politicization of aesthetics,” it is fairly tepid, concerned far more with content than with form, but it is obviously markedly different from what “establishment candidates” usually put forth, which is to say nothing of how it compares to Trump.

Is it radical enough? Well, what is “enough”? The full on expropriation of the culture industry into the hands of cultural workers? The subsequent institution of democratic control over record labels, art galleries, publishing houses? The providence of community resources so that artists might have a chance to explore the limits of their creativity without being hamstrung by marketability? Sure, but all of that is just rhetoric in the here and now. The challenge is to connect it to the politico-cultural expressions emerging at this particularly heady moment, to figure out what parts of these expressions we can move with the grain of and which ones should be hedged against.

I will not be voting Democrat whoever winds up on the ballot come November (and no, that’s not an “official Red Wedge position,” whatever the blue fuck that would mean). But I cannot deny that there is a certain “Berning” to be felt. The question springing from that is how to make it more than a feeling, more than aesthetics, no matter what happens in November. It’s not easily answered, but if we can ask it right then there might be something very promising on the other side. And it won’t be held back by a coin flip either.