I recently had the great pleasure to speak with visual and performing artist Andrea Barr, currently working in Berlin, Germany. Among our many candid conversations have been the current political climate, youth movements, and Black Bloc tactics in Germany. We have also been talking about hospital rooms, bad internet connections, bourgeois love, and good sex. I count myself lucky to know such a mind, and to know her work. These conversations produced a series of questions which you will find us exploring below. It gives me great pleasure to introduce her work to a new audience, and bring it into a dialogue of revolutionary art practice.

Read moreFeeling Trapped in a Dead-End System? Cartoonist Stephanie McMillan’s Affirmations Encourage Resistance

Activists and organizers for social change undoubtedly experience periods of burnout. Working long hours — typically without pay and little appreciation — on campaigns, issues and causes where victories are few and far between can be demoralizing. Some activists get so frustrated with the perceived lack of results from their hard work, the divisions within the Left, and the rampant apathy among the general public that they give up entirely and retreat from activism.

Cartoonist, writer and organizer Stephanie McMillan saw the depression, feelings of hopelessness and other difficulties faced by her fellow activists. And she wanted to do something to help people overcome these. So she started writing uplifting messages to empower individuals to continue working for a better world. She calls her inspirational messages “Daily Affirmations for the Revolutionary Proletarian Militant.” Similar to the memorable characters in her popular comic strips Minimum Security and Code Green, McMillan’s affirmations are accompanied by cute and colorful animals, plants and insects.

Read moreNovember: On Making Contemporary Anti-Capitalist Art

November is a recently formed and democratically run network of anti-capitalist visual artists, formed for “mutual assistance; to promote work; to share ideas for anti-capitalist strategies in contemporary art; to cultivate the working-class audience for such art; to counter the echoes of post-modern cynicism; and to build practical solidarity with today's struggles.”

Read moreLet's Get Free: Living Hip-Hop History Fifteen Years Later

dead prez ( © Zubari, 2008), the cover art from Let's Get Free (Loud Records, 2000)

Rap duo dead prez exploded on the hip-hop scene 15 years ago like a Molotov cocktail. Their debut album Let’s Get Free, released March 14, 2000 on Loud Records, excoriated injustice with unabashed revolutionary bravado. Together M-1 and Stic.man revived the prophetic and political potential of hip-hop at a time when crass commercial rap further entrenched itself on the airwaves. Dreadlocked and militant, the MCs tackled mass incarceration, school indoctrination, and Black socialist liberation. They situated themselves as belonging on the spectrum “somewhere between N.W.A and P.E.” The 18-track effort seamlessly wove hints of jazz, poetry and the blues into its seditious beats.

Let’s Get Free bristled with a sense of urgency like on “Police State” where the lyrics decry, “And the people don't never get justice / And the women don't never get respected / And the problems don't never get solved / And the jobs don't never pay enough/ So the rent always be late / Can you relate? / We livin in a police state.” Masterfully mixing together speech excerpts between songs from Uhuru Movement founder Omali Yeshitela and historical voices of Black Panthers like Fred Hampton and Huey Newton, Let’s Get Free paced itself like an incendiary mixtape whose community ended up being a global one.

On February 10, dead prez performed Let’s Get Free as an album show for the first time ever at the Observatory in Santa Ana. The sold out crowd clamored as “Wolves,” a Yeshitela speech set to music played. In the greenroom, Stic.man sipped on herbal tea and did pushups. The duo readied themselves for the moment with a ritual pouring out water and voicing their offerings. They emerged from behind the curtain as “I’m a African” echoed through the walls of the venue. Fans faithfully recited the lyrics of every song as the duo powered through “They Schools,” “Propaganda,” and “Psychology,” before bringing things to a fervor with “Hip-Hop.”

The night cemented Let’s Get Free as all too resonate today to simply rest upon its well deserved mantle as a masterpiece of political rap. Before and after the show, I spoke with dead prez about the album and their recollections making it.

What was dead prez before Let’s Get Free?

M-1: I met Stic in 1990-1991 in Tallahassee, Florida. I attended Florida A&M University. We were young people trying to figure out the world, that’s all. We studied revolutionaries and thought we might want to be revolutionaries. That’s genuinely what created dead prez. It wasn’t contrived from a concept at all. It was actually the lives we were trying to live and figure out through our pursuit. A lot that, of course, was based off our political ideologies. I quickly passed through a stage of being a student on campus after two or three semesters. We ended up forming an organization called the Black Survival Movement. That movement led to us joining other political organizations. That journey is still happening. It’ll never stop. For me, music was a way to do what I couldn’t do with a leaflet in my neighborhood. That’s who we were before the actual name "dead prez." Before that, we were a group called The Masses Want War and actually we were The Heads From the Attic and then there were several MC crews in that big crew.

The back story behind the album also included taking a risk in moving to New York. What was that experience like?

Stic.man: We had a vision based on our love for Mobb Deep and Wu-Tang Clan at the time. They happened to be our biggest influences and inspirations. We lived in the South, in Florida. In order to get our voice heard with the type of music that we make, we needed to be in that environment. We were going to move to New York and attempt to sign to Loud Records or somewhere similar and have a better chance than the booty-club type of music in the South. A lot of our homies in our neighborhood and other talented artists, we got nine of us together and a little bit of money, maybe like $600, and we moved to New York. Of course, that ended super fast. The next thing you know, we were staying with my girlfriend’s sister and just had the luck of an electric fire in the wall that made it obvious that there was too many people in the apartment. That was our last day there. Over time it just got to the point where the money we had couldn’t add up and the subway began to be the overnight place to live. The year that we were there, I think in ’94, there was one of the worst blizzards. It was my first time seeing snow. We were literally knee deep. But we had our vision, our dream to stay and continue. Over time, we ran into Brand Nubian and Lord Jamar. We started working together and actually signed with the label we initially wanted to.

What are your thoughts looking back at 15 years of that album?

M-1: Let’s Get Free alone was like the contents page to a book that we wanted to write. It talked about what might be covered inside the book but it still had a lot to go. It was a statement that we wanted to make to the world that we thought we might not be able to make again, you know what I’m sayin. We wanted to able to say all we could while we could say it.

Stic.man: Let’s Get Free really was all of the demos and all the studio time in Florida, all the experiences in the political education and being members of the National Democratic Uhuru Movement. All the demos in Brooklyn and getting a demo that got us signed and then working on songs to see what the album would be like, all of those things became 20-plus years of our lives.

How resonate do the messages of the album remain today?

M-1: Politically for me, I think it was prophetic in a certain way. Since then we’ve been, in many different ways, touching on the same stuff that has primary contradiction in the things that produced the songs in Let’s Get Free. We’ve been able to understand that contradiction from the beginning. It hasn’t moved or changed. The same problems we had before is the same problems that we’re having now. What we have been trying to do for many years since Let’s Get Free is talk about it in different ways and not make the same ol’ song over again. I could, in fact, make the same song over again because they’re still relevant in that way. It has absolutely nothing to do with me or Stic in an egotistical way. We just study. We’re just social scientists. We study the world and figure out how to change it. Anybody who is trying to do that is going to make the same noises we making.

How did “Hip-Hop” come together in the studio? And is it true Kanye West co-produced it?

Stic.man: There’s a big myth that Kanye West produced our song “Hip-Hop.” That’s one of the biggest myths about that album. The raggedy bass, I actually produced that. Kanye West produced the remix. I was in the studio. We had most of the songs recorded already. We had the vision. We knew the direction the album was going. We were trying to make a well-rounded record, but we didn’t know what would be a single. I was at a place that we called Warrior Studios and I was working on the ASR-10, the old 16-bit sound. I remember when I was growing up in Florida the whole thing about music that drove us crazy was the bass and just seeing the woofers just vibrate. At that time, East Coast hip-hop, there was bass but it wasn’t like 2 Live Crew bass. In my mind, I was just looking to create a bass that rattled like back in the day. I started playing around with the wheels on the ASR-10 and I was literally making a joke when M1 and about six homies came into the studio. I had the basic drums and bass. “Whatchu workin’ on,” M1 said and I was like “Yo, check this out.” I made up “It’s Bigger Than Hip-Hop.” I didn’t really know what that meant. I just knew something was going to go on the hook. He just looked at me like “Dude, that’s crazy!” M1 started writing and then I ended up writing my verse. Then we played it for the label. Instantly, they all was like “that’s the single, that’s what we’ve been waiting for, let’s go.” That ended up being the lead single and to this day our biggest tune.

Chairman Omali Yeshitela’s speeches are peppered throughout Let’s Get Free as well as voices from Black Panther history giving the album a political mixtape feel. How did that come together?

M1: Well, like I said, it wasn’t contrived. It was actually the lives that we lived. We met the Uhuru Movement who gave us the majority, the brunt of our political education and our actual work, not just songs. We were part of many real campaigns that organized around this country. I only trained in that job as an MC because I think people can relate to the message that comes from this kind of music. That’s why I wouldn’t ever make any other kind of music. To me it would abandon what I came in it to do. For the way it sounded, we wanted to make a statement in a time when people weren’t making it anymore. The people who taught us, that’s what their job was. The KRS-Ones, the part of Big Daddy Kane, the part of Rakim that gave us what we are, you know what I’m sayin’. We knew we had to make that statement. That’s why it sounds like we learned from the Black Panther Party because we were definitely doing that and actually involved in Uhuru. It wasn’t like we stumbled across a Chairman Omali speech. I was there for that. I recorded that with my own microphone. I was organizing. I would take that and go right into the street. That’s why it’s in there and that’s why we’ll never make another Let’s Get Free, because that moment was that.

Where do you think the album is situated in hip-hop history?

Stic.man: Humbly speaking, based on the cycle of growing up in today’s world, there’s always going to be that age where we come into an awakening politically. When we was growing up, Rodney King was the situation that was a national outrage. When the Panthers was growing up it was people like Emmett Till. Each generation, there’s been conditions that influences the consciousness of those times and the music documents that. We didn’t set out to do that, but what we realize is that Let’s Get Free marked that process of people coming into the realization that our condition needs to change. That’s going to constantly happen as long as there’s oppression. The album has had this much longevity because there’s people constantly turning 13 and there’s constant evidence of the Reagan, Bush or slavery era. It became a soundtrack to waking up and inspiring consciousness, resistance and change along the line for some people as reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X. We’re just part of our history. That’s what the album captured.

How was it performing Let’s Get Free as a live show for the first time?

Stic.man: I’m just grateful to be a part of the experience and to have the opportunity to take something we would do for fun, for free, that was just our own therapy, our own realization process. To be able to share with our community, with the world, fifteen years later to a sold-out crowd in a city I’ve never been, you know what I’m sayin, for some people that probably wasn’t 2 or 3 years old when that record dropped. Man, it’s a grateful feeling. It’s also a bittersweet kind of thing to know that all of those issues are just as relevant now as opposed to we’ve gotten much closer to being like “Remember that, back in the day when people were oppressing each other? Remember when we solved that?” I’m grateful as a musician to have made some relevant music that can inspire people and give a voice to a marginalized condition. I wish our album was obsolete. Unfortunately, it’s still relevant in the present.

So what’s in the future for dead prez after the 15th anniversary of its debut?

M1: Who knows? We still here. Hopefully the revolution. That’s what it’s all for. We gotta win! Today, I’ve grown. It’s not static. I’m not dogmatic. I look for new approaches as to what we understand as our liberation and I’m open to that. But, what I do realize scientifically is that this is always going to be imperialism, we’re always going to be in the stages of imperialism and people have given us a great wealth of information about what that is. People like Frantz Fanon, Patrice Lumumba and Omali Yeshitela. They’re great revolutionary theorists. Revolution is good for us. It’s not a fringe or extremist thing.

dead prez is a revolutionary hip-hop duo based in New York City. The group's albums include Information Age, Revolutionary But Gangsta and Let's Get Free, which features the well-known track "It's Bigger Than Hip-Hop."

Gabriel San Román is the author of Venceremos: Victor Jara and the New Chilean Song Movement, co-creator of the 2015 Calendar of Revolt and a writer with OC Weekly.

Freedom and Imagery: A Discussion on Charlie Hebdo

Artist's response to the Charlie Hebdo shootings by Australian artist and socialist Van Thanh Rudd

It has been a full month since the office of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo was attacked by two gunmen in Paris, leaving eleven people dead (including the magazine’s editor and three of its cartoonists) and injuring eleven others. The reverberations can still be felt: in the whipped up hysteria around “Islamic terror,” the increase of scapegoating against Muslims (particularly in France, but across Europe and in North America), and the renewed debate over the responsibilities and power of graphic artists.

Read moreArt (as Social Organism) vs. Gentrification

In late June, Chicago artist Amie Sell’s installation, Home Sweet Home, was unilaterally censored and removed from the Milwaukee Avenue Arts Festival by landlord and businessman Mark Fishman due to its criticism of M. Fishman and Co.’s role in the gentrification of the Logan Square neighborhood. The incident was covered in the Chicago Reader.

* * *

Adam Turl: Before talking about the incident at the Milwaukee Avenue Arts Festival (MAAF), I wanted to ask you to discuss your work more generally; this would include the relationship of your artwork to your community activism in Logan Square. According to the Chicago Reader you have lived in the neighborhood for more than nine years and you helped organize Somos Logan Square (We are Logan Square).

Amie Sell: Around 2010, I started a long-term art project that examines House/Home: A house being a container, structure and financial tool. A home being a collection of the intangibles: feelings of safety and security, relationships, emotions and memories. This examination began out of personal introspection and the realization that I have lived in 25 different structures and moved 27 times in my short life. In comparison with many people, this is unusual, but has just been how my life has unrolled; Growing up in rental situations, being part of a military family, independently working my way through college and for the last 9 years living in the 60647 zip code.

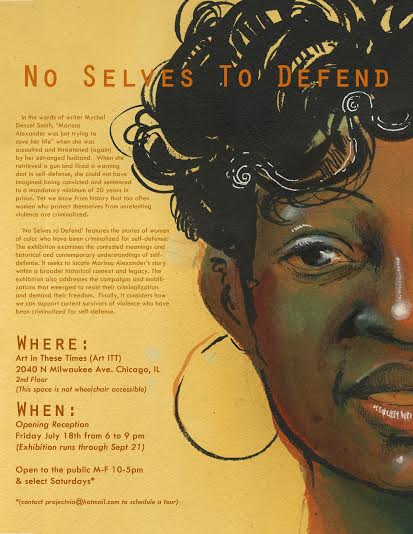

Read moreNo Selves to Defend

On July 18, an exhibition called “No Selves to Defend” opened in the Art In These Times space in Chicago. The opening was a fundraiser for the legal defense fund for Marissa Alexander, a Florida woman facing up to 60 years in prison for firing a warning shot in the air when her abusive ex-husband threatened her and her young children. Ashley Bohrer talked with one of the exhibit’s curators, Mariame Kaba, who organizes with the Chicago Alliance to Free Marissa Alexander and runs Project NIA, a grassroots organization with a vision to end youth incarceration.

* * *

Ashley Bohrer: How did the idea for this exhibition emerge?

Mariame Kaba: Four months ago, I decided to do an anthology project around the concept of “No Selves to Defend,” an idea that I’ve been writing on and off about for the past few years, but have been thinking about for much longer. In the context of Marissa Alexander’s case, for which I’ve been doing advocacy and support, we wanted to find a way to raise money and educate the public around women who were criminalized for defending themselves. I reached out to friends who were artists and writers to contribute to creating an anthology that would put Marissa Alexander’s case in a historical context of women who have been criminalized for defending themselves. The idea was to have a portrait of each woman and a description of her case. We completed the anthology in 6 weeks and put it up for sale in our Free Marissa online store. And we thought that one of the ways to expand the project was to do an exhibition, pairing the portraits with ephemera and historical pieces including vintage photographs, pamphlets and fliers from defense committees in the past. The ephemera and artifacts come from my personal collection. The exhibit came out of the anthology project.

AB: What has the response been like to the anthology and to the exhibit? Have people been responsive and receptive to the work that you’ve been doing?

MK: The response has been really overwhelming. People were very excited that the anthology project was happening. When we put out a preview piece, it was widely circulated on social media. We made a limited number of 125 copies and we sold out of them in a very short time. People were very interested in trying to understand and learn more about women who have been criminalized. Some of the names – Joan Little, Inez Garcia for example – might have been familiar to folks, but others are more obscure to people. Bernadette Powell and Cassandra Peten were not household names. I think people are interested in this history and in supporting Marissa Alexander’s case. It’s been a really great response, a wonderful turn out to the opening and I’m very pleased about how people have been responding to it.

AB: Why do you think there’s been so much positive response to this project at this moment in time? Do you think there’s something about the discussions and debates in the left or in the broader public that are contributing to this response?

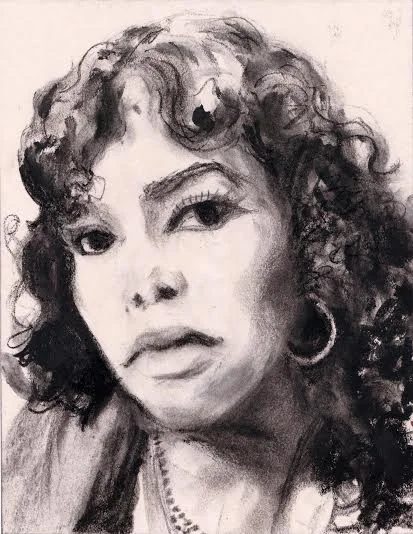

Inez Garcia” by Bianca Diaz

MK: I’m still unclear if the broader public cares very much. In the left, we are in a moment of thinking about the idea of mass incarceration and hyper-incarceration. In the last five years, more people have come on to this idea. And people have become more interested in prisons more generally. Some have even called the struggle around prisons to be a new civil rights movement, though I’m not sure I would call it that. This project and this exhibition were working to illuminate the logics of incarceration and how they structure our lives in various ways. And we’re in a moment right now when there is a greater ability to reflect on these issues than there has been in the past. But in the rise in consciousness around mass incarceration, one of the things that’s been missing has been a conversation about gender, whether that means transfolks or LGB folks or women-identified folks. Many of the conversations have been dominated by talking about men of color because they have been caught up in the system in such high numbers. But wherever there is the possibility to deepen and complicate that story, people have been interested and wanting to engage with it. This project has been a part of that.

AB: Could you talk a bit more about the title of this project — “No Selves to Defend”? What is distinctive about the way the system of mass incarceration targets women-identified people?

MK: We are dealing with mass criminalization and mass incarceration is only part of mass criminalization. We have to look at how the police target various peoples, communities, and bodies. We have to look at the ways in which hospitals, social services, the punitive nature of criminalizing poverty, and how other structures are implicated. We’ve been seeing, for example, more stories of women who have been criminalized for leaving their children alone during the day because they have no childcare. When we think about prison, we usually think about men; we usually think about black men. And that makes sense because they are disproportionately targeted by the system, but we should also think about black women. I looked at numbers of people admitted to US prisons in 1904. I had a copy of a report that I found at a library used book sale. And I looked and saw that at that time, almost 150,000 people were sent to prison that year. Out of that, 136,000 are men and 13,000 are women. The interesting thing to consider when you look at those numbers is that black women are disproportionately incarcerated even compared to black men. And this trend continues for a while. About 15% of incarcerated men are black or called ‘Negro’ at the time, but 21% of women incarcerated were black.

It’s always been the case that black women have been de-gendered within the system. It’s why discussions of black transwomen, no matter how you identified whether you saw yourself born as a woman, you were not treated as a woman. For white women, prison was very much a last resort and they were more likely to go to a reformatory. But those who were sent to custodial institutions, where black women were sent, were subjected to all kinds of abuse, sexual and otherwise. White women were always seen as redeemable, even though some of the ones who transgressed were punished harshly. Black women are still fighting to be seen as ‘legitimate’ women. They have historically not being able to claim access to being women and are still fighting to be seen as such.

The other thing to consider is that black women are black. To this day, black people are fighting to claim their humanity. We are seen as inhuman and disposable. And so when that is the cultural script around you, this leads to disproportionate treatment and makes it very difficult to claim that certain things like rights and resources rightfully belong to you. And when you’re seen as unhuman, it is hard to claim the status of corporality, being a body, and being a person. This is part of the struggle, learning how to combat and remedy that perception and therefore the treatment that you receive. That’s part of what the conversation is about. That’s what it means to have “no self to defend.”

“Yvonne Wanrow” by Ariel Springfield

In a broader way, when we talk about social locations, women are subjected to particular kinds of violence within prison that some men can escape. I’m not talking here about sexual violence, as men are also subjected to this as well. People who identify as women, broadly speaking, or who can become pregnant, are subjected to things like shackling during childbirth. Not something that men are subjected to. The way the carceral state operates is around the gender binary, so I speak with that understanding. Women giving birth are shackled. We also have to talk about the effects on families and communities when women who are primary caregivers – and many women are, as this is still how society is structured – are taken out of the household. This is hugely devastating. It is for men too but in a different way. It is important to think about those kinds of things in relation to the targeting of certain bodies and their differential experiences.

AB: At the opening reception for “No Selves to Defend”, there was a photo booth in the back room, inviting attendees to take photographs holding signs that said “Prison is not Feminist.” How do you envision this slogan being a part of the exhibit and about the message around mass criminalization?

MK: Prisons are not feminist. There was a time when feminists were not just involved in the conversation but were in the lead of prison abolition. That happened in the 1960s and 1970s. If you look at articles in Off Our Backs,Through the Looking Glass, and other publications, you saw feminists wrestling with questions about justice and police brutality and the need for prisons to come to an end. It was always contested, but in the 80s the anti-violence movement went 100% into being partners with the state and the gatekeepers of the state, the police. This happened because of funding considerations and the fact that liberal feminists believe in using the courts and the police to deal with violence against women and girls. They think it’s not only viable but desirable. They think that the police should be more responsive to claims of violence. This engendered the rise of ‘carceral feminism’. Carceral feminism is ascendent in many ways in the feminist movement because the real estate on anti-violence work was too limiting. They are now doing a lot of stuff on trafficking, conflating trafficking, sex work, and prostitution. And it is definitely about arresting people. Sometimes it’s about arresting johns, or pimps, or even the people who trade sex themselves.

At the exhibition opening, I wanted to say very clearly: prison is not feminist. When I think about feminism, I think that it means that we all deserve to live self determining free lives, free from exploitation, transphobia, violence, racism and oppression. We deserve those things. And prison is the opposite of that.

Prisons are constitutive of violence in and of themselves. They cannot be reformed and therefore prisons cannot be feminist. We wanted to make that explicit. Some of the very laws that carceral feminists are pushing have boomeranged onto the survivors of violence who are being swept up into prison based on these laws. The collaboration between the anti-violence movement gave the state legitimacy and allowed it to co-opt some of our ideas to grow a prison nation. We have to provide our own solutions that would be more in line with feminism. We cannot continue to feed the machinery of this rapacious, horrifyingly destructive system of incarceration. That’s part of what the intervention was about.

We also started Prisonisnotfeminist.tumblr.com so people can keep adding to this project beyond the exhibition. We encourage others to start posting their images with this slogan to get these ideas in peoples’ heads, especially to those who feel they are feminists or who identify with that word.

AB: What do you think is the role of art in the fights to end criminalization, racism, and incarceration? How can we think about the relationship between art and social justice activism?

MK: I wrestle with this a lot. A friend of mine invited me to be part of a conversation that they’re curating this fall at SAIC, where they are trying to have conversations about whether or not social justice and art go together. And as I was thinking about it, I started to think about all of the different kinds of art interventions Project NIA has been involved with over the past five years. I didn’t even realize how often we rely on art to illuminate ideas and impact changes in policy, structures, and culture. I think art offers the opportunity for people to think in a different way about issues. If you see something visually stimulating, it allows you to have your imagination activated in a way that words do differently. I think both are important and married together can be impactful. I also think that art hits us emotionally in a way that other things can’t. Art can also reach across differences in a unique way. I’m interested, as an organizer, in trying to find ways to connect with people where they are, to engage them in their communities, to engage them in their interests. And a lot of people are interested in art in its various iterations. It’s been organic for us at Project NIA. And it’s something that I did as a very young organizer in high school, using films and art and storytelling to talk about racism, to discuss issues with youth. It helps people to be able to unleash their emotions and to imagine something very different than the world we live in. For me, I’ve also seen art be a platform to be able to have difficult conversations and for people to feel less threatened, to be able to open up these dialogue and conversations about difficult issues.

I should also say: art doesn’t replace grassroots organizing or advocacy on the ground, but art is often used in the service of social transformation. I have a lot of friends who are artists. I like artists. My friends who are artists are more able to access certain parts of their psyche to imagine something different. What we need desperately right now is people with imagination to think about something different and who aren’t afraid to go there.

AB: Has Marissa Alexander seen the anthology?

MK: We sent her a copy of the anthology. I haven’t heard back from her yet. Her mother, who is very active in Free Marissa Now, has thanked us for this work and the Chicago-based organizing around her case. I won’t speak for her, but this project responded to something that Marissa said. She’s been asking the national mobilization committee to highlight the fact that her case is not singular, that she is not the exception, that rather, many women have been criminalized for defending themselves. Marissa has always said that she wants other peoples’ stories to be lifted up by hers. Part of our work has been to raise other women’s stories too. The idea for the anthology came from hearing Marissa’s mother and through her Marissa saying that she doesn’t want this campaign to be just about her, but to place her story within a historical context. I think for that reason she’d be pleased about what we’re doing.

AB: What else is the Chicago Alliance to Free Marissa Alexander doing right now? Are there other events on the horizon?

MK: We just got done with a month of solidarity events. We did a teach-in, the opening, the next day we screened “Crime After Crime” and then we had a large community gathering with artists and performers. We also co-hosted an event about breast-feeding and incarceration in late June. Marissa’s trial was supposed to start on Monday (July 28), but it has since been moved to December 8. There will be an event co-sponsored by CAFMA focused on anti-prison organizing and anti-violence organizing on October 16 at DePaul University. Dr. Emily Thuma who is a professor at UC Irvine wrote her dissertation on the history of the anti-violence against women’s movement and its intersection with the anti-prison movement. The title for her talk is “Lessons in Self- Defense: Women’s Prisons, Gendered Violence and Anti-Racist feminisms in the 1970s and 80s.” I’ll be speaking at that event as well. We’re also currently discussing solidarity events in the lead up to Marissa’s new trial date, which is December 8.

“Dessie Woods” by Rachel Galindo

AB: How can people support the Campaign to Free Marissa Alexander (CAFMA) and Project NIA? How can they support a project of ending mass criminalization?

MK: They can follow Project NIA and CAFMA on Facebook so they can keep track of upcoming events. CAFMA meets on the last tuesday of every month. They can visit ChicagoFreeMarissa.wordpress.com to find out when meetings are. The best way to connect with CAFMA is to come to those meetings and we operate through collaboration. People can also donate to Marissa’s defense fund. We have a Free Marissa store (link) where they can buy things. We’re also accepting donations from artists so they can be sold and all the proceeds go to Marissa’s defense. Our work at Project NIA is different. We have a Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) teaching collective that hosts a PIC 101 training that folks can attend. We also have a project called Girl Talk led by a collective of young women who go into the jail once a month who do art projects with young women on the inside. We’re about to launch a books to youth in prison project where we’ll be sending books to the Department of Juvenile Justice. There will be a call for participation. Follow us on Facebook and keep track of our blog.

Lastly, I would also say that people should keep in mind the importance of not contributing to more prisoners, of not contributing to more criminalization. Think about why you are calling the police. Even if you can’t be involved in doing advocacy, think about in your life personally how you can not contribute to criminalization. If you’re not calling the cops, if you’re watching them, if you can make sure not to contribute to the machinery of the prison industrial complex and mass criminalization, that’s also very important.

“No Selves to Defend” is on display in the Art in These Times space, located at 2047 N. Milwaukee Avenue in Chicago. The gallery is open to visitors between the hours of 10am and 5pm, Monday through Friday until September 21, 2014. If you want to attend on a Saturday or would like a group tour, contact Mariame at projectnia@hotmail.com.

Mariame Kaba is the founding director of Project NIA. She has been active in the anti-violence against women and girls movement since 1989.

Ashley Bohrer is a feminist and PhD candidate at DePaul University.