Certainly, such a system need not be reminded that the game pieces are human. Florida Governor Rick Scott recently mocked the very study of humanity when he asked, “Is it a vital interest to the state to have more anthropologists? I don’t think so.”(Of course we all know that the state of Florida has little interest in what it means to be human.)

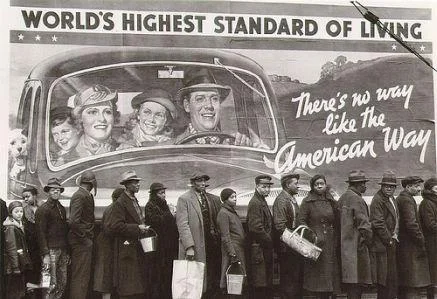

What is vital to the neoliberal state (not just Florida) is unfettered capital. The humanity, creativity and potential of the state’s citizens are irrelevant beyond perfunctory appeals for votes and consent.

Neoliberal Models of Education and Culture

Obama, since taking office, has led the neoliberal attack on education and culture — most notably promoting former Chicago Public Schools CEO Arne Duncan as Secretary of Education.

While Obama has, in recent years, proposed art funding increases on the federal level — knowing full well the Republican House of Representatives would balk — he has, more often than not, led the way in cutting arts funding. In the 2012 budget Obama proposed a 13 percent reduction in National Endowment for the Arts funding and across-the-board cuts in other federal art and humanities funding. He has also yet to appoint a permanent head to the NEA since its previous chairperson stepped down in 2012.

The emphasis on math and science and the degradation of liberal arts and the humanities is designed for a particular outcome: a small army of technocratic managers on the one hand (the people who design “just-in-time” production and distribution models and create exotic financial instruments) and an army of semi-skilled and unskilled interchangeable low wage workers on the other. The in-between working-class jobs, teachers and nurses for example, are constantly squeezed between the skilled realities of their work and the demands of capital.

Too often would-be defenders of art meet the enemy on the enemy’s terms. For example, Carole Becker, the Dean of Columbia University School of Arts, has argued that art education is a form of creative research that appeals to today’s employers. This is true at one level. Capitalism continues to need specialists (even if it needs less of them). As Mark Graham notes on CounterPunch, a 2011 survey showed that 92 percent of former art majors were employed — just over 40 percent as “professional artists.”

Even Forbes noted that only .02 percent of working-age adults with college degrees had been art history majors, and while working-class and poor students study art history it is a field that tends to draw students from middle and upper-class backgrounds whose studies can be underwritten by the financial security of their families.

Regardless, Becker’s defense of art on neoliberalism’s terms concedes too much ground to the enemy. The problem with the “capitalist realist” attack on the arts and humanities is that it is:

1.) It is an attack on the very essence of what it is to be human.

2.) It is an attack on human labor itself.

Art with a capital “A”

Art is more than a series of skills that may or may not be of use to the corporate world (where artists become “culture workers” as Theodor Adorno put it).

When we talk about art with a capital “A,” we must reckon with “big” questions. Our present-day Thomas Gradgrinds, referring to Charles Dickens’ humorless cheerleader of industrialization in Hard Times, do not want us to discuss the “big” questions in a meaningful way. (In Hard Times, Gradgrind torments a little girl because, rather impractically, she loves horses.)

In the art-world, the most notable Gradgrinds were the post-modern ideologues, who, like evil fairy-tale wizards, hated “big” questions, stories and narratives.

As Mark Graham argues, “As much as we live in a material world, we also inhabit a symbolic order in which we can’t help but wonder why there’s something instead of nothing, who we really are, and what death means for us. Art may not provide the answers but it gives us an outlet (that science does not) to ask insoluble questions without resorting to the dogmatism of institutional religion.”

“Marcuse argued that it was art that could imagine an alternate reality beyond the one-dimensionality of operationalism,” Graham continues, “and the totalitarian powers it serves. Art is an ‘inner history of the individual’ that serves as a ‘counterforce against aggressive and exploitative socialization.’”

“Jack Kerouac described [art] as ‘the unspeakable visions of the individual.’ [Herbet] Marcuse as a ‘liberating subjectivity.’ [John] Berger as a dissolution of the self and other.”

“Art is an expression of man’s need for a harmonious and complete life,” as Leon Trotsky argued, “his need for those major benefits of which a society of classes has deprived him.”

For the Marxist art critic Ernst Fischer art was a rebellion against being forced to consume ourselves within the confines of our own individual lives. It was art that allowed us to achieve the fullness of existence through multiple viewpoints, narratives and experiences.

We would argue that it is art that allows us to connect the mundane, fantastic and horrible realities of everyday life with the uncharted horizons of an emancipated human imagination.

Whole Foods Market, Jamba Juice, Starbucks, McDonalds and Wal-Mart have no need for this sort of dreaming. In fact, such dreams manifested in their employees are an objective threat to the vulgar rule of Corporate America.

The act of combining this human creative experimentation with knowledge of history is all the more objectionable for the 21st century Gradgrinds.

While art historians are not known as a rowdy proletarian mass, the field of art history represents a large part of what a post-capitalist society would be about: unleashing (and understanding) the collective social genius of the human race.

In this sense art history is, objectively, a beachhead of the future socialist society. It is tolerated in this system as a sort of hobby for bourgeois and petit-bourgeois children. But art history, rooted in the genius of our species’ origins and tracing the arc of social development and class conflict is dangerous.

It remembers — and remembering is the cardinal sin of neoliberal capital. Capitalism is a system of forgetting.

Once upon a time the most favored art of the bourgeois was history painting. For the revolutionary bourgeois history was a weapon. Think of David’s Oath of the Horatii and Death of Marat and the French Revolution. History painting was also a weapon for those who opposed (from an aristocratic, plebeian or disillusioned liberal point of view) the new order. Think of Goya’s Execution of Peasants on the Third of May.

As John Berger argued, history painting eventually became empty and scholastic. As history became the enemy of the new ruling-class, history painting became hagiographic. Artists rebelled against this empty history painting in the 19th century and asserted the essentially modern aspects of art.