“Polysemy (from Greek: πολυ-, poly-, "many" and σῆμα, sêma, "sign"), the capacity for a sign, such as a word, phrase, or symbol, to have multiple meanings, usually related by contiguity of meaning within a semantic field.” – definition adapted from Wikipedia

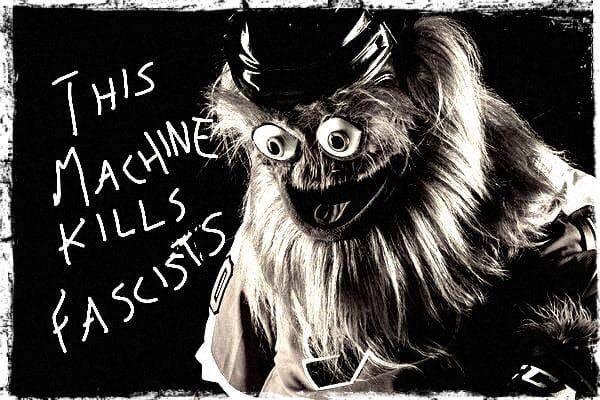

“If you cannot convince a fascist, acquaint his head with the pavement.” – Gritty (probably)

Now is the time of monsters, the well-worn phrase tells us. But monsters, if they are interesting, are unpredictable. They come out of nowhere and evince their nowhere-ness, their improbability creating fascination, fear, revulsion, sympathy.

Think of Frankenstein’s creature, that original monster of modernity, crudely stitched together from discarded bodies, never having asked to exist, lumbering through a world that both reflects itself in him and shuns him save for the most compassionate of individuals. Or Godzilla, the irradiated gigantic lizard, pummeling cities with the same obliterative force of the atomic bombs that created him. Both bring with them abject shock and terror, but with a logic underneath, a consequence that in retrospect seems inevitable, our most repressed fears made manifest.

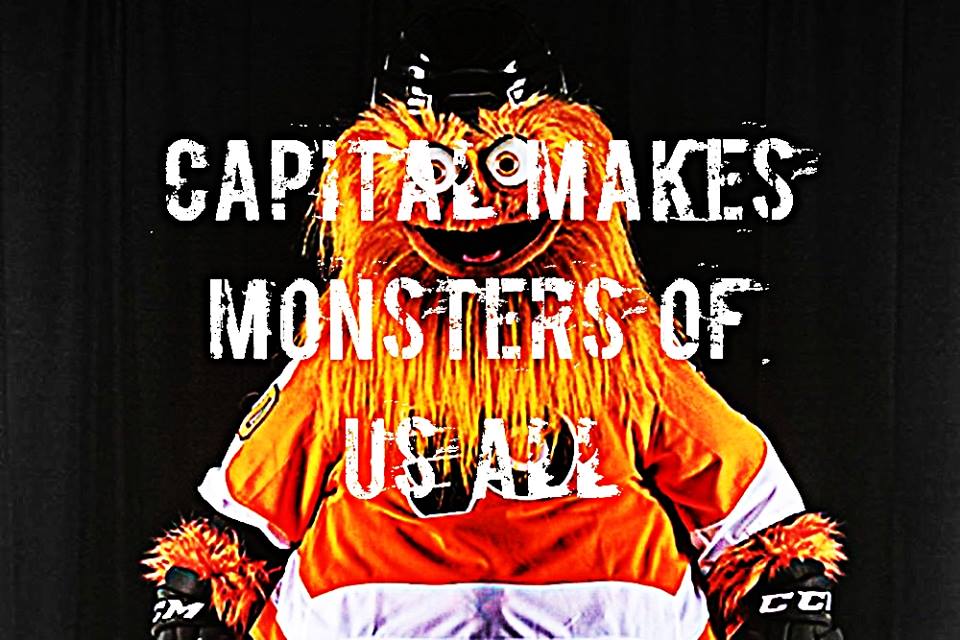

Now consider Gritty. What could be more improbable than a sports mascot initially labeled “nightmare fuel” becoming a symbol of resistance rather than mere #resistance? And yet here we are:

He is best and most affectionately described as a freak, a mutant-demon muppet, a humanoid thing with wild orange hair, googly eyes, and a grin that has seen horrible things happen. It must be why he is always wearing a helmet.

At first he was reviled, with coverage from the sports press predicting his fate shoved into the back room with so many other failed marketing gimmicks. Others loved him immediately. In fact, a greater number than might have otherwise been expected. Even those well outside of Philadelphia or hockey fandom (such as this writer) were delighted by his emergence.

Yes, delighted. Tickled by the same nerve that causes us to laugh when we see the villain in a zombie movie ripped apart and devoured. Given permission to indulge in our own freakishness whether we regularly wear ice skates or not.

Then came Donald Trump’s visit to the city, and the counterdemonstrations that nowadays seem to follow him like toilet paper stuck to the bottom of a shoe. Then came the pictures tweeted by George Ciccariello-Maher depicting Gritty as antifa. Then declarations from Jacobin that “Gritty is a worker,” and Twitter accounts portraying him as a member of the IWW. Then memes and socialist buttons and more memes and other signs on the protest. All displaying Gritty as a kind of apotropaic totem, a benevolent grotesque deployed against evil:

And then, inevitably, came the pushback from right-wing writers. “Antifa Appropriates a Creepy Mascot” read the Wall Street Journal headline. “Keep your Marxist hands off Gritty,” the article’s author, one Jillian Kay Melchior, demands. “He belongs to Philly.”

Not inauspiciously, that very same day the WSJ ran another opinion piece titled “George Soros’s March on Washington.” The author of that piece, Asra Nomani, spends its entirety painting protesters who opposed the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court as in the pocket of Soros, thus trading in the kind of anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that just a few years ago would have been rightfully marginalized and isolated to those who believed Hitler did nothing wrong, but now is common currency among the right-wing. Even Trump is trading in it.

Scary times. But then, the right has always sought to make us into something we aren’t. Be it through anti-Semitism or racism or just plain hatred of the poor, there has always been an effort to paint the left, or anyone who stands opposed to the current order of things really, as only nominally human. We are, for reasons perfectly rational in their eyes, to be feared. We are sinister, conspiring, savage. In short, we are monsters.

* * *

Without a doubt, much of the left’s adoption of Gritty can be chalked up to the proliferation of absurdity as a defense mechanism against the very real terrors of everyday life. Aided by Twitter and other social media, we glom on to the latest spate of bizarre in an effort to acclimate ourselves to the apparent unraveling of reality. Jake Blumgart at CityLab is on to something when he states that “Gritty is nothing if not the ultimate weird Twitter meme.”

There is furthermore something to be said for the specific location of Gritty’s adoption, if not psychogeography exactly then certainly the psychology of place. It is difficult to imagine him emerging or being so enthusiastically embraced outside of a city like Philadelphia. At least in this unique iteration. Philly is, as Ciccarriello-Maher puts it, “an underdog city,” a city that wears its crudity and weirdness proudly. It is a contradictory weirdness (as all weirdnesses are), but it is markedly different from the “keep our city weird” refrains heard emanating from Portland and Austin, increasingly an attempt to maintain cultural cache in attracting developers. In Philly one often gets the sense that the well-worn freakishness is in part a rebuke to the sanctimonious “city of brotherly love” bullshit, the pomposity of “America’s birthplace.” Writers like Melchior deliberately overlook this, and therefore the contradictions of Philadelphian life that lead to the organic existence of leftists, socialists, anti-racists who are also Philadelphians.

Beyond that, thinking more broadly, we might consider how it is that symbols are created in the first place, how something that has one meaning might take on another. How the time and place of an image’s creation allow its hidden and or unintended meanings to be pulled out and relayed through consciousness until its definition is thoroughly transformed. The reinterpretation and evolution of these meanings is a key animating force in cultural ritual. As such, it is a contest between competing forces whose visions of the past, present and future are at odds with each other. It is an act that reflects concomitant attempts to redraw more far reaching boundaries and expectations in the name of creating new spaces of shared identity.

Political and social struggle drive these processes. Particularly when the contradictions of a society are at their sharpest, often as a way of revealing, again, that the fears at its core cannot simply be swept under the rug. The gay liberation movement adopted the upside-down pink triangle that was stitched to the clothing of homosexual prisoners in Nazi concentration camps. This became even more prominent among queer activists in ACT-UP during the height of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. What was twenty years before a way of rubbing America’s nose in the stench of its own bigotry became a demand that the country pay attention to the Reaganite neglect that was leading to a new miniature Holocaust in the LGBT community.

There is an obvious wrinkle in all of this. It is not only left or progressive forces that have the capability to reshape meanings. Martin Luther King, who toward the end of his life was questioning the tenets of capitalism itself, is now used in bank commercials. But this is only the most obvious and glaring example. When a new music or fashion gains enough popularity from the bottom-up, it inevitably becomes something administered from the top down. Its jagged edges are filed off, its oppositional being remade as something worn by capitalism’s cooler faces.

What’s more, anyone familiar with the alt-right will know well enough that they are adept at their own versions of this. Matt Furie famously hates that his creation Pepe the Frog became a symbol of fascists, but the memes and momentum of that movement have been far too much to bend things back to his will. For better or worse, most people who see Pepe today are bound to think of roving gangs of white supremacists. Indeed, there are already several Gritty vs. Pepe memes.

And here is the point, the way in which a contest for ideas in the real world spills over into the worlds of the un-real. What writers at the Wall Street Journal are so displeased with is the idea that the left might yet again gain any cultural purchase, might flex any capability to disseminate its own myths and jokes and phraseologies into the world at all. That it have a symbol for anything past the old dusty aesthetic scraps of hammers and sickles. This is an unpleasant thought for respectable defenders of the current order. Particularly when it is done with a corporate sports mascot. Such brazen disrespect for cultural propriety is something that, while it may not dispossess them of everything that should be ours, at least makes their skin crawl. Which is precisely why we should keep doing it.

* * *

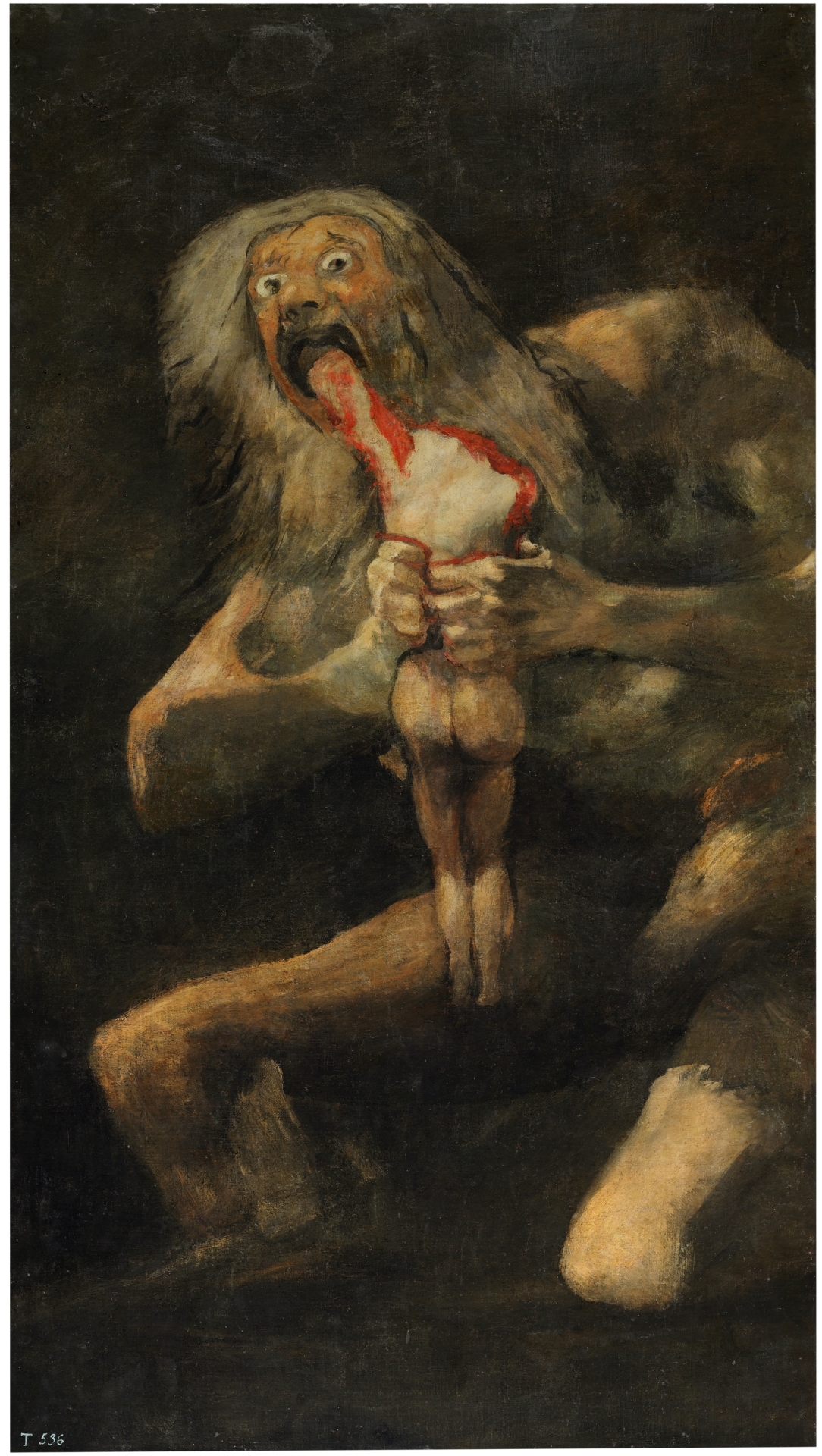

The most striking of all the Gritty signs on the recent Philly anti-Trump protest deserves analysis in itself, portraying the orange oddball consuming a pants-wetting Trump, in a direct reference to Goya’s Saturn Devouring his Son:

Goya’s original painting is haunting and disturbing. It originally was displayed on the wall of his dining room. Part of his “Black Paintings” phase, it was painted during Napoleon’s invasion of Spain, and is thought by many to indicate a growing malaise in the writer’s mind concerning the increasingly chaotic and unhinged state of the European continent.

Of course, times of great social unrest are like that. They fill us with dread but also hopes for something that might be able to be pulled from the wreckage, a humanity underneath the monstrosity. Those willing to stare into it long enough might be able to discern the two. And maybe might be able to find something to laugh about.

It is worth dwelling a bit on this: laughter. The parameters of humor are themselves drawn and redrawn to reinforce certain ideas of permissibility. Many new waves of comedy have also shocked, made uncomfortable certain people in a bit too much comfort in either their station or simply their preconceived notions. Think of Richard Pryor, Bill Hicks, Eric Andre.

But a new line of humor, a new transgression of the social mores – be it good or bad, progressive or reactionary – only takes hold if it reveals something about the audience to itself. What it does with that reveal is often up to where the punchlines lead.

The maker of the Gritty-as-Saturn sign is still at it. They are creating a series. A series of Gritty incinerating and dismembering alt-rightists and anti-choicers. There is a gleeful nihilism in these drawings; one that tugs on the same nerves of horror and humor and extends them into a narrative. Where will the eldritch icon of anarchy and revolt turn up next? It’s a silly question to ask. Not just because it involves rooting for an escapee from Jim Henson’s secret dungeon, but because much the answer depends on how much deeper the new left is willing to take its stories and reinventions.

Because the ability to reinvent, redefine, reclaim, is one that is often grotesque and weird. It is also joyous and often hilarious. Because capital makes monsters of us all. Because in doing so it invites vengeance and chaos made manifest in everyone cast aside. And because maybe we see these reflected back at us in the stare of a creature who is never defeated in its maniac ugliness. And maybe that’s an instinct worth exploring.

This essay first appeared at the Red Wedge Patreon. If you want to get early access to content like this, as well as other exclusive, subscriber only material, the support us today!

Alexander Billet is a writer, cultural critic, and founding editor of Red Wedge. He has written for Jacobin, Chicago Review, In These Times and other outlets. He is slowly working on a book on music and geography, and lives and otherwise itinerant existence in Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter: @UbuPamplemousse