Karl Marx writes in Estranged Labour* that, accepting the presuppositions underlying political economy as it existed at the time of writing, one can see that there is a hell of a lot missing. There is something to it – but it is insufficient. As Marx writes, political economy “expresses in general, abstract formulas the material process through which private property actually passes, and these formulas it then takes for laws. It does not comprehend these laws – i.e., it does not demonstrate how they arise from the very nature of private property.”

One can say the same thing about the dominant form of writing about popular music. It can provide you with consumer knowledge with perhaps a tad more (but only a tad) than an algorithm. Capsule reviews, publicist-doctored Wikipedia entries, Rolling Stone, The Source, Pitchfork, tenured musicologists and middlebrow New Yorker writers, all of them assert an aesthetic, a “way of listening” to play on John Berger, without providing a metric of qualitative assessment beyond bourgeois notions of “taste”.

This, the dominant means with which popular music is written about in 2018, is something we can call “descriptivism” – that is to say, mere description of a cultural artifact without any reference to temporal or geographic specificity, class, race or gender. Descriptivism, if done accurately, can be useful – who doesn’t want a description that captures a song? Fat bass, big beats, minor keys. A good purveyor of descriptivism will have the capacity to describe a piece of music by using generally understood language – so “fat” bass will be generally meant to connote thick, resonant and low notes being played on a bass guitar. Reviewers at the collective endeavour known as AllMusic.com do a good job with descriptivism, and in the case of some, notably Stephen Thomas Erlewine, actually bring in a bit of context. But most of the time unless one is familiar with specific subcultures, the language of descriptivism assumes what needs to be explained. Like Straussianism with political theory, it explicitly divorces art from craft and both from history, geography and conjuncture. Yet like Marx wrote of classical political economy, at its best, it provides the rudiments.

A lousy purveyor of descriptivism creates an insularity with their writing, and – more or less – merely writes advertising copy better conceived as a longform Facebook post in the guise of writing about music. Shuja Haider’s recent devastating critique of Pitchfork is implicitly based on this insular form of writing, this “jargon of authenticity” bound up with a healthy amount of tokenism and exoticization. Haider’s celebration of country music does not take for granted a metric of qualitative assessment. Instead, Haider provides one both grounded in his own experience and predicated upon a description that grasps the internal connection between affecter and affectee. This can be contrasted, on the other hand, with the wretched likes of Chuck Klosterman and his “edgy” revival of Billy Joel as a working-class hero. Klosterman provides no metric by which to qualify why Billy Joel deserves rehabilitation – no analysis of his cross-class appeal in the American northeast, not even an engagement with Joel’s own view, not unreasonable, that he was given a “bum rap” by critics.

Billy Joel, lifelong anti-fascist deserves better than to be revived by Chuck Klosterman

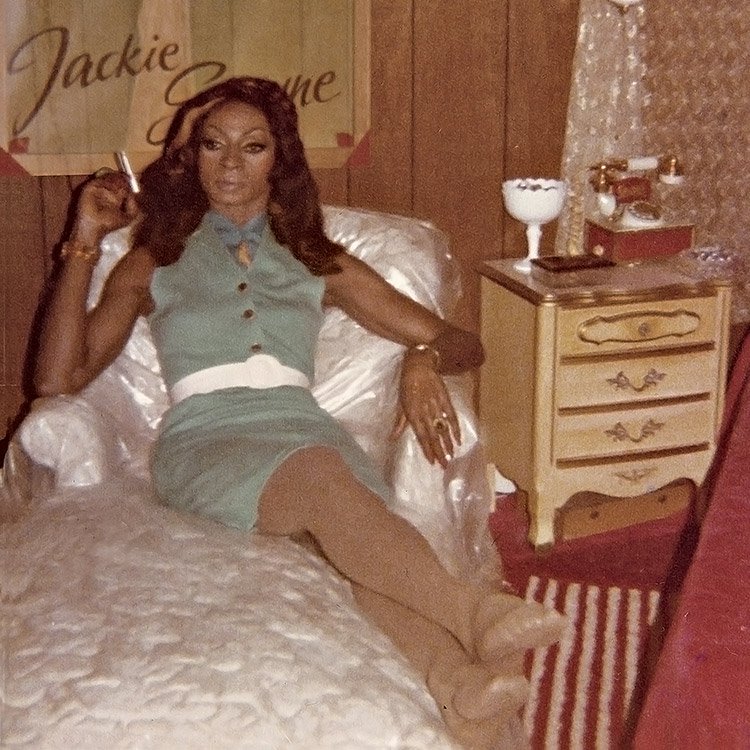

Thus it is not surprising that, even in academic so-called “musicology” with regards to popular music, descriptivism reigns supreme, and gatekeeps fiercely, quite unlike other cultural forms, or even other musical genres. Take the York University professor Rob Bowman, nominated for a Grammy for his liner notes – essentially ad copy – for the brilliant recent Numero Group compilation of the Toronto-based sixties soul vocalist Jackie Shane’s previously hard-to-find output. We shall return to the gate-keeping and perhaps queerphobic Bowman. Or take the Cold War historian Sean Wilentz’s notes for Bob Dylan albums. Take the entire industry of nerdy “scholarship” around popular music, Dylanology, and the propensity to elevate Dylan’s proverbial Grundrisse, music released as “Basement Tapes”, as something beyond stoned demo tapes recorded in a basement, improvisation – brilliant stuff but emphasized for the wrong reasons.

Arguably, this mythologization and descriptivist jargon is at least rudimentarily based on the liner notes on the back of Blue Note and Prestige jazz records. At the very least, however, Nat Hentoff and others were judicious in their prose, and helped the listener make sense of which saxophone player played which solo, and thus, how to distinguish, say, an alto from a tenor sax, or the rumbling drums of Art Blakey from the delicate tone of Elvin Jones.

Indeed, this idiom is rooted in the problematic popular front practice of creating myths out of what became known as “folk music”. Along with the mythmaking descriptive writing, often involving the devil and the Crossroads and the fetish of the “murder ballad”, there was the common practice of often Communist Party affiliated cultural commissars going to the American south and rural areas in general, making field recordings and crediting themselves (and in doing so, cashing in). The most notable of these was Alan Lomax. “Is there another human,” great lefty music writer Dave Marsh once quipped, “in the history of our species who could get away with this kind of robbery-not only of money but of credit and historical recognition – and be acclaimed a hero?” As Marsh says of Lomax,

The most notorious (legal claim against Lomax) concerns “Goodnight Irene.” Lomax and his father recorded Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter’s song first, so when the song needed to be formally copyrighted because the Weavers were about to have a huge hit with it, representatives of the Ledbetter family approached him. Lomax agreed that this copyright should be established. He adamantly refused to take his name off the song, or to surrender income from it, even though Leadbelly’s family was impoverished in the wake of his death two years earlier... Lomax believed folk culture needed guidance from superior beings like himself. Lomax told [WBAI interviewer Peter] Bochan what he believed: nothing in poor people’s culture truly happened unless someone like him documented it. He hated rock’n’roll – down to instigating the assault against Bob Dylan’s sound system at Newport in ’65 – because it had no need of mediation by experts like himself.

Alan Lomax, OG fanboy, gonif.

Thus we see that musicians Lomax recorded struggling for crumbs from the table, and while they have been revived in a mythological sense, there is a false concreteness to how, for example, antiquarians like Jack White or Ken Burns – or Rob Bowman – attempt to play an Alan Lomax role by proverbially “reviving” proletarian and often African American cultural production. This can be contrasted with a countertendency, such as the role initially played by the likes of Harry Smith in his own folk anthologies, not pretending to be a discoverer, and instead of attempting to create myths, merely putting out comprehensive collections of music, often at a loss, but always with a mind towards artists at least gaining some degree of recognition. And this then goes to the likes of Numero Group, a label that puts out excellent material, yet takes pains to brand itself, as opposed to truly revive the careers of the artists they put out. Indeed, this can be contrasted, as Bowman can be to the likes of Dave Marsh, with other specialty reissue labels, like Light in the Attic. Not only did LITA help revive Sixto Rodriguez’s art, but they created the impetus for Searching for Sugar Man and thus, Rodriguez now is able to make a living again as a touring musician. He doesn’t languish in obscurity and LITA is not out to grab attention for itself. Notably LITA has done more than any other reissue label to revive the storied legacy Indigenous rock music.

So thus we see the tendency and countertendency but the tendency towards descriptivism and mythology still reigns supreme. This is largely due, during the rationalization of the popular music industry in the mid to late sixties, to the dominant form of capsule review found in outlets like the far-left Ramparts as much as Rolling Stone. The early days of rock music criticism, far more so than the pretensions of Pitchfork and its ilk, genuinely attempted to, as Robert Christgau put it, inflect their writing with the zeitgeist – they were all, after all, leftists – the artists, the audience, the critics.

Yet, as I’ve written at length elsewhere, there was a missed encounter of a real cultural alliance between the Bohemian rock music culture and the organized socialist Left. And the critics – Christgau, Ellen Willis, Lester Bangs, Patti Smith, as they often have been, had feet in both camps, as Christgau says, too hippie for the Lefties, too political for the hippies. Yet they were certainly explicitly close to the Left, Christgau and Willis in particular, with Willis going on to become the renowned socialist feminist theorist that she is known of today. Willis was foundational in inflecting the real poetics of genuine “rock criticism” with gender, race and class analysis. Christgau, her partner at that time and lifelong friend, brought in a sensibility informed by, yet challenging Dwight MacDonald’s Adornoian critique of the culture industry, the idea of Mass-Cult and Mid-Cult. Seeing the masses as in revolt against the capitalist class and yet voraciously consuming rock music, Christgau and Willis’s approach implied that rock music as form not be reduced to the commodity form, but simultaneously needed to be understood as a capitalist commodity, without one project outweighing the other. In the terms of Walter Benjamin, they wanted to maintain the aura.

Ellen Willis, the greatest rock critic of all time.

Similarly, in the pages of the New Left Review, between 1967 and 1970, Perry Anderson and David Fernbach and some others debated what was presumed to already exist, a “Rock Aesthetic”. Not committing the error Marx described of assuming what needed to be explained, Anderson and Fernbach situated the need for a rock aesthetic conjuncturally. Anderson called rock music the first truly communist art form, breaking down the barrier between performer and audience, affector and affectee. This required explanation, and Anderson proceeded to provide exquisite analysis of the Rolling Stones – a favorite of the cultural Left, notably Godard, predicated primarily on their subject matter and peripherally on their performative style. He counterposed the Stones to what he saw as implicitly bourgeois and mannered in the Beatles (not the first time Perry Anderson would be wrong!), or inauthentic in Dylan (same!). Fernbach did not disagree with Anderson but added an axiological dimension, finding Anderson’s purely contextual approach insufficient. Fernbach adduced a set of axioms by which rock music could be assessed, axioms that would need to be analysed and explicated in both specific and historical contexts, and thus applied to an individual art object. Thus, a qualitative assessment that moves beyond simplistic ideas around “taste”.

In the fifties, the Italian Marxist Galvano Della Volpe asserted that taste was essentially a bourgeois phenomenon but affect production cannot be reduced to or deduced from context. There needed to be an approach that moved beyond categorical slippage between an individualist assessment that could not explain the endearing quality of great art, or a historical approach that reduced greatness to ideology or superstructure, as if to write capitalism into human history and the laws of commodity production onto artistic creation. The point, to Della Volpe as to Christgau, Willis, Anderson and Fernbach in their own ways, was to oppose both the fetishization of a false concrete implicit in descriptivism and individualist approaches as well as the reductionist approaches that, on the left, tended towards a social conservatism and/or a tendency to attempt to instrumentalize and make didactic, as that was art’s purpose. To Bertolt Brecht, art wasn’t just a hammer, even if it couldn’t escape being one. What was being implicitly sought was a counter-canon formation, a connection between rock music and a popular avant-garde. A taking of rock music seriously not in spite of it being a popular art form but because of it being a popular art form and demonstrated human achievement equally worthy of analysis and celebration as any previous canon. And this sensibility could be spread, it was thought, in writing.

Alas, as Christgau writes, they were forced, after a while, to write what became capsule reviews. Rolling Stone stopped printing Lester Bangs, who moved on to Creem Magazine, an originator of a specific aesthetic but part of a transition point from counterculture to a series of subcultures. “Too bad you missed rock and roll” Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s Lester Bangs character says to a young Cameron Crowe in Crowe’s film Almost Famous. Crowe cannily shows Bangs’ counterposition with what he justifiably saw as The Doors’ inauthenticity, essentially bad acid poetry, with the working-class schmaltz of the Guess Who. And while plenty of great rock music has obviously existed since 1971 or so, the role of the critic has fundamentally shifted. Critics went from participants in a counterculture of a new form to kingmakers, career makers. There were always greats, like Christgau and those around the Village Voice, Jim DeRogatis and a few others in Chicago, but these were exceptions to the rule and they weren’t in the “rock media” like Rolling Stone, they weren’t kingmakers. Even critical favorites like Neil Young famously admonished them in “Ambulance Blues”:

So all you critics sit alone

You're no better than me

for what you've shown.

With your stomach pump and

your hook and ladder dreams

We could get together

for some scenes.

And how was it they made these scenes? By mythologization and pedantry, by fetishization of technique, by fickleness. And this generation became redundant with the growth of alternative newsweeklies and new forms of in-group subcultural jargon, their aesthetic, the pedantic descriptivist, the fetishizer of the bootleg and the unreleased, the cataloguer became a trope. Indeed, what Haider engages with Pitchfork is the current ossification of the alternative newsweekly “critic” form, as much as Rolling Stone was in the seventies, or The Source has become for hip-hop.

Counterculture becomes subculture. And in the midst, you have the constitution of subjectivities like that that exists with the trope of the superfan. The likes of Rob Bowman, for example, writing a vivid and exceptionally readable yet monochromatic account of the amazing rise and fall of Stax records, interviews hundreds of people but never really lets them speak, as it were, he frames what they have to say. If one is not already a fan of soul music, one will not come away from Bowman’s text with any more desire to delve into the great catalogue produced at Muscle Shoals. This is quite unlike, for example, my own experience reading Frederic Jameson or Edward Said, or wanting to watch Cronenberg films and read Jane Austin, even though neither had been within my range of sensibility before reading either of them. All the pedantry and positivism and fanboyism in the world won’t make up for ignorance of the dialectic!

Rob Bowman, descriptivist bro par-excellence. Doesn’t know what “queer” means.

Bowman and his whole generation of descriptivist are monochromatic. As Marx puts it, in their approach “the theologian explains the origin of evil by the fall of Man – that is, he assumes as a fact, in historical form, what has to be explained.” And it is no wonder it is the likes of Bowman, now crediting himself as a producer, and Numero that are receiving all the attention around the Jackie Shane reissue, culminating in the Grammy nomination. Shane’s story, which has been told quite well elsewhere, notably in Any Other Way: How Toronto got Queer, named for her classic soul song, in which “way” rhymed with “gay”. Shane was a trans woman performing kick-ass, blues-inflected soul music that absolutely embraced its explicit queerness, especially in live performances, in Toronto’s mid-sixties Yonge Street music scene, the scene that produced The Hawks, later to be known as The Band. She was an exceptional performer, later even asked by George Clinton to join Parliament-Funkadelic.

In Bowman’s informative and fanboyish liner notes, however, while paying liberal lip service in a sort of “Toronto the Good” fashion to the “acceptance” or “tolerance” of Shane, Bowman makes the implicit point that Shane didn’t “play the trans card”. Like in the Stax book, while Bowman did interview Shane, who has been reclusive since the early seventies and perhaps had no say in the matter one way or another, he does not capture her experience. He does not convey why her art is so vital or elucidate the meaning of the success of a trans soul singer in sixties Toronto. For that one has to look elsewhere, as Bowman is serving the ideological function of downplaying Shane’s gender.

Like the Stax artists as well – he is especially fetishistic about the fact that the label’s house band was integrated – he repeatedly, to all questioners, downplays Shane being transgender. Truth be told, one cannot expect much more from a tenured musicologist known to sell himself to libraries as an expert appraiser, known to throw his weight around at Toronto’s record stores. One cannot expect much more from someone who, while briefly serving on a PhD examining committee as an external examiner, attempted to correct a dissertation that he later refused to examine, by bleating that Lou Reed and Janis Joplin weren’t queer – “they were bi”.

This is to say, to be clear, Bowman doesn’t know what queer means in the way it has been used for at least a quarter century. To say he’s queerphobic is perhaps a stretch but he certainly presumes a mass queerphobia and thus tails that presumption. This is all redolent of his pedantry and the general poverty of descriptivism. Thus we see a straight line from the “progressive” Stalinist Alan Lomax ripping off poor black folks and “hilbillies” all the way to white saviours like Rob Bowman “rescuing” Stax records and Jackie Shane, while writing nearly laughable liner notes. At least advertising copywriters don’t pretend to be something they’re not...

So what is needed beyond descriptivism? Dialectical analysis. This is not some kind of Marxist fallback into jargon and metaphysics. This is analysis of form that actually analyses it in its multidimensional quality. You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows, so to speak, thus you don’t need a dog-eared copy of Ollman, Dietzgen or Lukacs to be a dialectician! Yet this approach provides an inherent challenge to the gatekeeping of the descriptivists who, like all gatekeepers, are aware of challenges to their hegemony. Thus accommodation is made with these gatekeepers on matters particular, like, say, punk rock politics or the political economy of the record industry. But a sensibility that actually takes popular music seriously – academically, among critics, and indeed among socialists – is something that is already taking shape, in the pages of Red Wedge and at our panels, as well as elsewhere. And the descriptivists can keep winning Grammys.

The exquisite Jackie Shane deserves better than Rob Bowman!

*Special thanks to Jules Gleeson for the suggestion of the classic 1844 manuscript as a starting point.

Jordy Cummings teaches Political Economy at York University and has been called the Tinpot Beria of the Counterculture. He is an editor at Red Wedge.