I.

Poor Mike Pence. Greeted with a friendly gaggle of actors who both recognize him and are willing to express well-meaning concern over the havoc he may wreak as vice president. Pity too Donald Trump, who now feels blindsided by the realization that the theater isn't somewhere he and his cohort can retreat from the consequences of their actions.

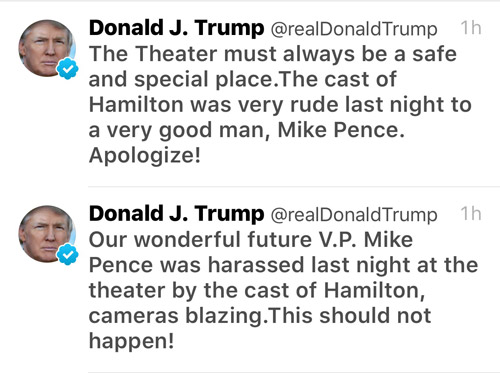

Trump's reaction is what ultimately makes the action of the Hamilton cast a Good Thing. The man spent fifteen months using his own bully pulpit in a far less kindly way. He urged supporters at rallies to assault protesters, announcing he would pay for the legal defense of anyone who did. So much for “safe spaces.”

Donald Trump has never been a man afraid of using theatrics to get what he wants, including the White House. For it to reach beyond his grasp, for it to come back and bite him a little bit, for it to expose his hypocrisy – even in a slight way – is gratifying. All the world's a stage, Donny...

At the same time, there is now a narrative arising that, far from being a situation that Trump and Pence haplessly walked into, and far from Trump's reaction being some kind of petulant temper tantrum, the whole thing may have been a savvy calculation designed to exacerbate divisions and continually paint the incoming administration as the victim of lefty bullying. Some are even suggesting the controversy was concocted as an effort to distract from the president-elect's settlement of $25 million in the Trump University scam. If either are true, then it would certainly confirm that Trump remains an expert aestheticizer of politics.

There's a question that rises to the surface with incidents like these. What, exactly, do they accomplish? And with that, should theater be expected of accomplishing anything? And, if one can't offer up a solid answer to these, then does Trump maybe have a point about art staying within its confines? By no means easy questions.

“We are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us, our planet, our children, our parents, or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights, sir,” went the statement read by star Brandon Dixon. “But we truly hope this show has inspired you to uphold our American values, and work on behalf of all of us.”

Nice words. Kind words. Virtuous words. Hardly the kind of thing that could really offend anyone. Trump's tantrum notwithstanding, Pence has since claimed that he indeed “wasn’t offended.”

Might that be the problem?

Anyone who is in fact alarmed at the Trump presidency, the rancid record of Mike Pence, and the gaggle of white supremacists both will be working with in the upcoming cabinet can't help but admire the willingness to break form and speak directly to an audience member of Pence’s notoriety.

If their aim was to start a dialogue, then it would seem Dixon and company may be succeeding. Or maybe not. We don't know for sure, and frankly, we aren't supposed to. So often when we speak of art as fostering discussion, said discussion takes place in some nebulous realm half-detached from the world of a mass audience. How do these discussions impact how we live or how we think? The answers are vague, which means that necessarily they favor the ideas and discourses among those who have power, a narrative that suits the fairly passive expectations in contemporary theater of what an audience is expected to “do” (i.e. very little).

And this is the rub: discussions, appeals to a powerful individual's reason seem chalk history's worst crimes up to mistakes, as if a person's bad moral judgment is all that stands between them and concentration camps. It is, to be blunt, the blind spot in so much of contemporary liberalism.

It's not difficult to tie this rather soft method of opposition into the a production like Hamilton. There is, of course, a reason that the show became such a smash during the tail end of the Obama presidency. Hamilton is liberal America's superego, how it envisions its ideal, multicultural self. The America that is “already great,” whose racism and colonialism is an aberration rather than a key part of its genetic makeup.

This is not to deny the critical charge of the musical's concept, nor that there are a great many progressives, leftists, radicals who resonate with it on a sincere basis. Recounting the story of a historical figure like Alexander Hamilton with actors of color – using rap no less – is an inversion bound to be provocative in the 21st century. But the limitations of its content hinder its formal subversion.

The shortcoming of non-confrontational forms of theater is the same shortcoming Stokely Carmichael identified in non-violence: it assumes your enemy has a conscience. Pence has none. Or at least he has learned to swallow it so thoroughly that there is no coughing it back up.

Oddly enough, the audience themselves seemed to grasp this. Less reported has been the jeering and heckling of Pence that came from the seats several times throughout the performance. It was far less polite than the cast seemed to be.

In light of this it may be worth imagining a different tactic. Imagine Lin-Manuel Miranda himself coming on stage, wheeled in a trashcan pushed by Immortal Technique, who has also just finished giving the MacArthur Award recipient a lesson in capitalism, colonialism and Theater of the Oppressed. Miranda then stands up, points directly at Pence, and announces “this man has threatened to deport your family and lock up your friends. He now has the full apparatus of the American state at his beck and call. Not just its bureaucracy, but its violence too. He has no qualm with using either of them.”

Then, turning to the audience: “Why are you letting him leave?”

II.

There is a certain line of thought out there about acts like Green Day. It's a fairly tiresome one, one that is applied in a one-size-fits all way to any number of successful acts with roots in the American punk scene, but stubbornly refuses to die. If you've sold millions of albums, and if it's been through the medium of a major label, then you're a sell-out who has forgotten the raw, underclass audacity you came from.

It's an easily caricatured take, if only because it refuses to consider the way in which acts have to navigate the upper echelons of the culture industry and how their own search for artistic autonomy can create some wonderfully discordant results. This isn't to say that Green Day haven't had some very anodyne moments, but their act at the American Music Awards wasn't one of these.

Attempting a one-to-one comparison between the above and the Hamilton appeal is bound to be sloppy. There are far too many differences in terms of medium, form, content and intent. On one end, Broadway actors, singers and rappers; on the other white rock stars performing at a televised award show. But the outward frankness of this off-script segment, its direction not to the powerful but to the viewers, its usage of US music that has unjustly spent decades on the fringe of popular culture; these are features that point a far more effective mode of artistic resistance.

MDC, the group whose lyrics Green Day used for the interlude in their performance, have always been one of those quintessential American hardcore bands, in that they seemed to be all of those things one associated with hardcore punk during its “glory days” in the Reagan 80's. Loud, fast, aggressive, politically left and earnest to the point of crudity.

Crude it may be, but the formula has proven to be a potent one, or at the very least pliable and re-usable. Dave Dictor has been tinkering with the song's opening refrain (originally “No war / No KKK / No fascist USA”) to include Trump for at least the past month, and versions of the same have been incorporated into demonstrations against neo-Nazis and racists going back three decades.

There is a particular resonance now, however, in tying together Trump with extreme, true-blue fascism. That much has been borne out by the white nationalists enthused by the election. It is quite stark: individuals like Richard Spencer can speak to not insignificant crowds, claiming that America's “greatness” is built on its whiteness, invoking straight-arm salutes and “heils” in the president-elect's name. Despite the hand-wringing on the part of news outlets (“Do we call them alt-right? Wasn’t it horrible that Spencer’s home address was made public?”) the immediacy of the threat is not exactly subtle. One gets the sense, from all of this, that attempts to appeal to the “better nature” of the enemy actually have no idea who the enemy is.

All of which highlights the need for an art and a politic that are more confrontational. One that views its parameters and those of contemporary acceptability as ultimately at odds. If said art is going to jump beyond the imagined limits of the proscenium arch, then where will it land? Where will it situate itself in lieu of the fences that delineate what art “should” be? Can it do more than just present us with history in a re-imagined form? Can it, in doing so, actually make an intervention into history?

Whatever the executives at ABC might have thought about this unrehearsed moment, that wasn't the point. Nor is Green Day's own politics, which, when decipherable, tend to be a hybrid of Food Not Bombs anarchism and left-liberalism with faint streaks of social democracy (Billie Joe Armstrong was a vocal Bernie Sanders supporter).

The point is that an audience – at the Microsoft Theater, but more significantly at home – were asked to join in a chant that called the danger of Trump for what it is. There are now younger Green Day fans discovering MDC for the first time, and with them a far-too-unacknowledged timeline of the the American underground. They are reading about how hated and feared hardcore punk was by a segment of middle America that wanted nothing more than to seal itself from the villains within. They are assimilating all of this with what they know about the villifications of hip-hop culture, of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, of other social and artistic milieus that scared the establishment.

An alternate sequence of events begins to take shape, in which ignored voices become the key players. And this timeline reveals so many of those crowing over Trump's victory to be incapable of cohabitation with decent human beings. What it still has to do is collide with the comforts of unchecked power and the polite discussions that allow it to remain unopposed.

A stretch? Maybe. A lot of cards have to fall in exactly the right place for the above to come true. But with Trump taking office in just under two months, popular culture's existence as a battleground for ideas is going become far more open, far more unmistakable. The kinds of narratives we can cobble together are going to matter. The gestures artists make are going to matter.

If capitalism is performative, then the revolution will be a masterpiece.“Atonal Notes” is Red Wedge editor-in-chief Alexander Billet's blog on music, poetry and performance. Follow: @UbuPamplemousse