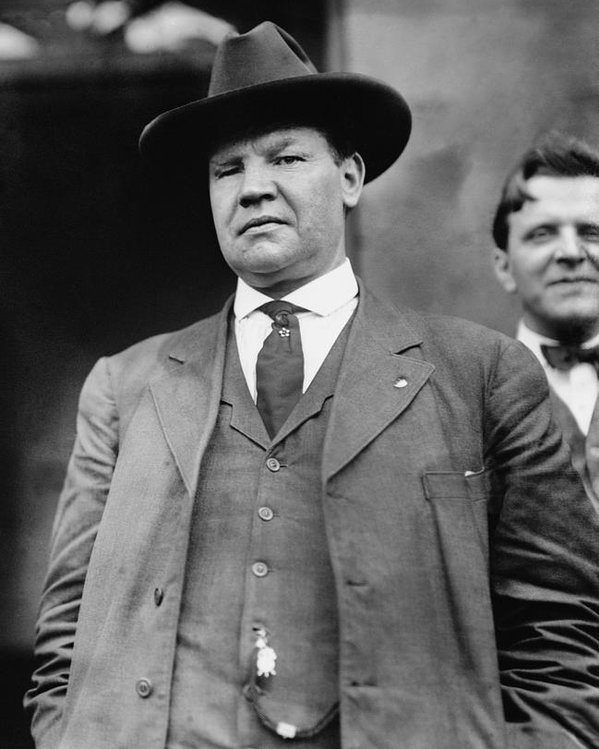

“Big” Bill Haywood

Marxism is many things. Whether or not one agrees with the likes of Michael Heinrich that it is not a worldview (I believe it most certainly is), it denotes a varying set of processes of collective and individual human practice and cognition. Whether or not you want to call that a worldview, well, you do you, boo. To define it is thus, in a sense, to engage in it. Marxism of course is not limited to being operationalized, as it were as a “discourse” or a set of written procedures. As is apocryphally told, the great American revolutionary socialist Big Bill Haywood once remarked that he neve read Marx’s Capital but his body was covered with “marks from capital”. Yet accepting the absolute primacy of sensual creative human practice, what Marx calls “form giving fire” of human labour, there is still the word and the set of words, the discourse, better yet, the rhetoric, or even better yet the poetic.

Attempting a process of interpretation of the world with the conscious purpose of changing it both through the mere act of interpretation – the mode of inquiry – and the act of articulating it – mode of exposition, lends itself, by necessity to a revolutionary poetic that can never be unseen, but is difficult to put into words as it lies somewhere between thought and expression. It is also important to note that sometimes interpretation that changes is not intended as such, yet becomes transformative through its polysemic quality. The written word itself, the use of rhetoric and tonal shifts, reversals and the like are the crust of this proverbial bread. Perhaps the foundational example of this revolutionary poetic, this upholding of Gonzo thought is the final chapter of Machiavelli’s The Prince. From sober, if sometimes emotive advice, Old Nick suddenly is a commanding voice, deliberately using emotive language to proverbially rile the reader and troll his rivals. It bears mentioning that conservative political thought in general and the Straussian tradition in particular blame everything on Machiavelli. Old Nick should have kept his mouth shut is Leo Strauss’s view, as should have Marx. They knew too much! They should have wrapped their writing up as enigmas wrapped up in riddles. But a revolutionary poetic, while understandable on many “levels”, creates an affect in its reader even if the reader is unaware at the time of its internalization.

I am here attempting to illuminate this revolutionary poetic. This is the distinction that one automatically gleans when reading, on the one hand, a revolutionary Marxist or otherwise anti-capitalist thinker, and on the other a liberal or even reformist/social democratic thinker – if both parties are being sincere in their invocation of, variously, a socialist project or a social democratic project. The rhetoric of lowered expectations and appeals to expertise cannot lend itself to stylistic development. An argument can be made that reaction can produce good writing, but never sober liberalism and social democracy. Never mind where one stands on the debate with regards to current Left strategy, reading Kautsky is boring. Reading Rosa Luxemburg is gripping. This is the same distinction that one even gleans - perhaps more easily, between hearing genuinely innovative and boundary pushing music, as against well executed example of an existing form. The latter may be quite satisfying, and as much as we can achieve for the moment (and perhaps preferable to the premature outburst of the former – there is nothing worse than bad experimental music), but the former is what music, indeed art itself should strive for. Yet it also strives for, whether or not this is the conscious aim of the artist, an ability to connect what is seemingly the most arcane with the broadest segment of people.

Karl Marx

And thus we come to the point of what kind of Marxist poetic speaks to the present moment? What is it about the growing desire to keep socialism weird, whether or not this point is even articulated or acknowledged? And with this need for weirdness, arguably since the election of George W. Bush, we’ve seen the flourishing of fine writers able to make the weird seem normal as normalcy right now is pretty weird. Along the way, as in the sixties among both Maoists like Progressive Labour and liberals like those who “stayed clean or Gene”, a general move casting a critical eye towards counterculture, has adopted a practically neoconservative analysis of the sixties counterculture in particular – take Angela Nagle’s citing of Allan Bloom’s Closing of the American Mind. Yet pushback, in these pages and elsewhere has stemmed that tide. Culture is important, and as I put it in my review of Nagle’s Kill All Normies, “even the Sober Teutons of the Second International had a Bohemian Streak”. From the most sober and sometimes upsetting analysis of rape culture, war and climate change to listicles about alienated labour, we see a “discourse” that is not “for” the movement but “of’ the movement. From Teen Vogue to Red Wedge, from Current Affairs to “even the New Republic”, a spectre haunts. This replacement of expert mediation with a dialectical raconteurish approach, an “in it together” demystification, this what I am thus calling a tendency towards a Gonzo Marxism.

In the aftermath of the long sixties, Marxist theorists from Althusser to Mandel proclaimed in one form or another, after all, that Marxism was in crisis. Althusser, the William S. Burroughs of Western Marxism, attempted to resolve this crisis by a near wholesale reformulation, along with a dispensation that others, like myself, would take to be key concepts. This is not to deny, however, Althusser’s influence, and indeed his later work on the aleatory quality of encounters informs my own framework as to the relationship between the far Left and counterculture in the long sixties. The key point, however, is that the crisis of Marxism in the seventies was that idiomatically speaking, with some notable exceptions, writing it had become nothing short of wretched. And even when not wretched, it had been detached, somewhat, from the social movements, and/or had “professionalized” itself into social science jargon, as in those around the Union of Radical Political Economists. A great deal of the best English language Marxist writing to come out of the sixties, however, were the not the ones who entered academia, they were those that wrote as situated explicitly as lifelong committed activists within the organized revolutionary Left - Mike Davis, for example. Kim Moody and Terry Eagleton were later academics, but their writing and agitation dates back to their days as socialist activists in the sixties, and those who entered the word of journalism, due to doors opened by the tendency of Gonzo Marxism. Even more salient to my own project is the late socialist feminist Ellen Willis, one of the foundational rock critics. She and Robert Christgau, one of the last of the great rock critics were indeed close to Marshall Berman, perhaps a patron saint of the Gonzo Marxist aesthetic as well as Bertell Ollman.

Of course when one hears “Gonzo”, one automatically will think of either the existentialist travelling muppet, or more likely Hunter. Thompson, who wrote the following,

There was madness in any direction, at any hour. If not across the Bay, then up the Golden Gate or down 101 to Los Altos or La Honda…You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning…And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil… We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave…So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark…that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

Looking back at the long sixties on the cusp of its slow denouement, in 1971. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is to the end of the long sixties what perhaps Walter Benjamin’s essays on hashish were to the Weimar republic. Demystification of an absolutely absurd reality was assisted, for Benjamin as for Thompson, by the use of mind-altering substances. While this is in no way an endorsement nor an admonishment for the use of cannabis or psychedelics, the opening of the veritable “doors of perception” arguably can allow the mind to capture the proverbial “real” beyond the fetishism of commodities. The politics of LSD, in the time of Thompson, like the Bohemian anti-capitalism of the hash eating hedonists that Benjamin and Bloch encounter, took it for granted that an acid trip would transform someone. Even its detractors feared this, as can be witnessed in a powerful exchange between Allan Ginsberg and a certain Ted Kennedy, during hearings before the criminalization of LSD in 1966.

Thompson was a journalist of the Left, idiosyncratic to be sure, a streak of American western individualism butting up against an instinctive anarchism and a lifelong “pure” hatred, in Alexander Cockburn’s terms, of the capitalist class. Perhaps he was not a communist or a socialist as he lacked faith in the masses after the defeat of the high and beautiful wave. The long sixties brought so much promise, especially for those middle-class baby boomers who had just become caught up with things but weren’t necessarily in the thick of it. Those that attended antiwar demonstrations, read Herbert Marcuse and Monthly Review, listened to the Beatles and Coltrane and smoked cannabis, the new subjectivity of the teenager that came to exist through historically contingent circumstances within the context of the post World War 2 economic boom, particularly on the American west coast, home of the counterculture.

But if Thompson merely lived to be a brilliant anti-systemic misanthrope who still rolled away the stone, his Gonzo method prevails. This method does not pertain to his inimitable style or his heavily constructed and exaggerated persona as pertained to the use of drugs. It doesn’t even pertain to his politics, as such, idiosyncratic as they were. Rather, like Benjamin, or for that matter Rosa Luxemburg or Karl Marx himself, he was a master not merely of demystification. He was a master of demystifying mystified bourgeois society as much as he was a master of mystifying the seemingly demystified, denaturalizing and questioning the prevailing set of social relations, raising the questions that history necessitated yet by nature and disposition, not providing “roadmaps of the future”, something Marxists must avoid in spite of the recent fashion towards seeing a project around “real utopias” as less of a transition than as a telos. As Ellen Meiksins Wood reminds us, Marxism needs no telos, indeed it has no telos, instead it is the appreciation for the tendency of those from whom surplus is alienated attempt to re-appropriate surplus, and in turn, how this class character – can – lead to socialism. And it can lead to the common ruin of the contending classes, an eco-fascist-in-one-country world order. To mystify common sense ideology, after all, is to prove that it is mysticism, and not the right kind of mysticism at that. This mystification of bourgeois mysticism itself is the key to the Marxist poetic.

This is not deconstruction, as the method being cultivated provides the skeleton key of reconstructing a more concrete totality between thought and expression. When we adapt a rhetoric that does not take as “givens” ideology as such, the naturalization of the wage relation, heteronormativity, the inherently rebellious nature of punk rock in the age of think pieces touting Fugazi as a start-up, we presume a set of logical procedures on the part of the reader that will encourage a demystification of what we ourselves by nature and standpoint mystify for both specific purposes and our own common sense. And that we have adapted a particular common sense, by osmosis and the labour of culture in general, to use Mark Dening’s term, we see our own cultivation, our own rolling away of the stone. A lesser writer, for example, would merely engage in descriptivism in writing about a criminal gang like the Hells Angels, as did Thompson in his early career. Thompson showed that “it’s all true” and then some. He demystified by mystifying the existing mystification. Suitable, then, that having told the truth, the Hells Angels beat the living shit out of him. Their presence among the counterculture was still romanticized, alas, leading directly to the murder of a black man at Altamont.

Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You presents us with the image of the grotesque telos of 21st century capitalism with its equi-sapiens. Humans are transformed with a magic powder into creatures with the strength of horses, combining the two mammalian creatures to be able to proverbially produce value for the human subject in John Locke’s original labour theory of value. This grotesque is there to represent the logical conclusion of the concatenation of surplus value extraction in 2019, maximizing both relative and absolute surplus value, both intensity of labour and time spent labouring. This grotesque, and in particular, Riley’s use of it is – precisely – what I am here calling Gonzo. The poetic of the best Marxist writing, thus, since the long sixties, has been a Gonzo poetic. Usually, in fact almost always, it is not a conscious attempt at a Gonzo poetic. Yet if the credo of Gonzo is when the going gets weird, the weird go pro, this is an implicit, albeit somewhat mediated claim that it is only weirdness that can capture reality. In a sense, when one reads the classic narratives of the failures of social democratic or left-liberal strategies of working inside the Democratic party, and the failure of that experiment, one cannot but be edified if one can situate oneself in the context illuminated by Thompson and his many talented contemporaries. There was a sense of playfulness in the written word in the unraveling years of the long sixties, and what marks revolutionary writing itself but playfulness?

I am engaging this point for Marxist writers – cultural theorists, socialist feminists, queer theorists, historical sociologists, historians, political economists and so forth – to at the very least entertain the notion of a Gonzo Marxism. I am not making the claim that the best Marxist writing right now is “square”, rather, I am pointing out the – existing – Gonzo tendencies within the existing orbit of Marxist writing as well as cultural production as a whole. Gonzo Marxism is merely Marxism. Yet it is a Marxism that pays special attention to the importance of discursive demystification in writing itself, and the operationalization of this demystification in human practice itself. Demystification in Marx often involves reversal, as in the cliché of “turning Hegel right side up”, or more fructuously, the declaration of the critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, that the crown makes the king. More often, and influentially, as in the case of the equi-sapiens, it is by virtue of introducing an historical materialism that looks at the logical conclusion of a given tendency, including its counter-tendencies, within the logic of process of capitalist social property relations themselves. Gonzo demystification, like the fiction/non-fiction hybrid of Thompson, or the realist/surrealist film and music of Riley, can cross the proverbial modernist/realist binary. But it is always presuming that we, the affector and the affectee, take for granted the need for profound reconstitution of society, implicitly or explicitly, revolution.

Wait –

But what, qualitatively speaking, what the shit makes it Gonzo? True Story! What separates Gonzo from “normie”, or to use a far less loaded term, “square” writing? One is reminded of Lenny Bruce’s routine, separating “Jews” from “Goys” in his imitable and profane fashion.

B’nai Brith is goyish; Hadassah, Jewish. Marine corps–heavy goyim, dangerous…

Kool-Aid is goyish. All Drake’s cakes are goyish. Pumpernickel is Jewish, and, as you know, white bread is very goyish. Instant potatoes–goyish. Black cherry soda’s very Jewish. Macaroons are very Jewish–very Jewish cake. Fruit salad is Jewish. Lime jello is goyish. Lime soda is very goyish…

Bruce’s “Jewish” here prefigures his contemporary Isaac Deutscher’s “non-Jewish Jew”, accompanied by a subtle dig at the fetishization of this very Jewish archetype. The ones who seek out Jewish sexual partners due to some Jewish essence. It is a celebration and an imminent critique all at once. If Gonzo can thus stand in here for “Jewish”, we can ascertain real examples from the time of Gonzo, which I will counterpose with “square”. Socialism from above is square, even or perhaps especially when it claims to be from below. Socialism from below is Gonzo as fuck, whether or not it sees itself as flowing out of the IS tradition. All Vice related publications are square. Teen Vogue is Gonzo, and, as you know, Grown-up Vogue is very square. Adolph Reed is square. Current Affairs has become very Gonzo after some years of Frosty squareness. Salvage is very Gonzo, even if it has UK characteristics. One of its editors indeed gave me the phrase “Gonzo Marxism” for an essay I contributed to them. Jacobin has a Gonzo streak and a Square speak, which is perhaps the right thing given its mandate to appeal to the left as a whole. There will always be “everyday” folks on the Left as the Left is the movement of the working class as a whole and the working class is pretty fucking weird. In these Gonzo times, a Gonzo Marxism can mystify our mystical common sense by never assuming what is to be explained, but also never attempting to explain that which cannot be explained in a matter-of-fact way.

Ralph Steadman illustration for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

After all, Marx was Gonzo. How did Marx find that indelible rhythm in his writing of the 18th motherfucking Brumaire? As Engels may have put it, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Marx had that rare skill that can only partially be captured by biography or philology. Althusser was right that Marx discovered a “continent of knowledge” but assumes what need to be explained. There is an intrinsic relationship between Marx’s young philosophical insights, his “political writing” and his mature development of historical materialism in the writing of Capital and the Grundrisse. That link is that Marx was as much as anything else, a journalist. Capital is many things, but it was a direct extension of Marx’s lifelong situating himself, professionally and politically, as a journalist in the classic sense of the term. Marx was a journalist in the tradition of the bourgeois revolutionaries, the pamphleteers. Journalism, to Marx, and indeed to Hunter S. Thompson, was seen as a tradition quite distinct from what should properly be called “reporting”.

Through this lens, the passages in the 1844 manuscripts in which Marx’s breaks the writerly fourth wall, the reversals, puns and in-jokes in the writings on Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, these are hints at the stylistic breakthrough, yet still inflected with a high German idiomatic tradition. Herr Vogt is high Gonzo, while the France writings – especially that fiery “Class Struggle in France” from his so-called Blanquist period – are simmering Gonzo. Capital is Gonzo in a sly way. Its form is often compared either a work of philosophy, such as Hegel’s Logic, or a great 19th century novel. Both points are true, yet miss the fundamentally original quality of Capital, in which the stylistic breakthrough is inseparable with the explanatory breakthrough. This is that Capital takes the model of a journalistic essay, an inverted pyramid in its mode of exposition. Starting with the commodity, the entire edifice of already-presumed-by-the-reader-to-exist capitalist mode of production and its social property relations are laid out. The fourth wall is regularly broken and levels of abstraction are introduced and thoroughly discarded once the concept no longer bares any use. Read properly and systematically, it is a trepidatious adventure but it is journalism, that is to say, the only plausible means with which to describe human reality in its material existence and in turn, the reality of exploitation and class struggle. Karl Marx was Gonzo.

Of course Gonzo is here being used as a signifier. A means with which to articulate a stylistic constellation and the political implication of a specific modality of writing one that can neither be reduced to nor deduced from mere technique. The experimentation or Avant-Garde quality of Gonzo is here being situated as a configurational question, to use Badiou’s term, it is a connection of spirit, not letter. The figure of Gonzo is the figure of the fool, and the fool is a figure of unique wisdom, albeit situationally appropriate. The fool can be foolish, perhaps sometimes even destructively so. Yet in their foolishness, their willingness to push limits and violate convention, their unwillingness to assume what has not been explained and their humility towards the moving parts of alienated social relations, they provide insight that cannot be provided by either the wise man or the genie or even the sirens. They demystify the mystified and mystify the prevailing mysticism. It is plausible that this was precisely how Hunter S. Thompson adopted the term.

The term “Gonzo” was first applied to Hunter S. Thompson’s writing by one of Thompson’s contemporaries, the Boston based gadfly Bill Cardoso. Cardoso, according to Thompson, sent him a note in response to one of his great early pieces of writing, a lampoon of the southern gentry-cum-bourgeoisie, titled “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” for Scanlans, giving his work that moniker. Thompson merely thought it was a Boston piece of slang for bizarre or strange. Cardoso at one point claimed it was a Quebecois term for “shining path”, yet social linguist Martin Hirst sees no evidence of the alleged word “Gonzeaux” ever existing, pointing to other likely evidence as to the “etymology of Gonzo”. Variously, it could be Boston-Irish slang for the last person standing after a night boozing away, a corruption of the Spanish word Ganso, colloquially meaning ‘idiot’ but literally “bumpkin”. The latter, to Hirst lends credence, to an extent, to Gonzo having a Quebecois etymology, given that Boston Irish slang, while mostly rooted in Gaelic, can be speculated to be not disconnected with the smattering of pre-revolutionary Quebecois settlement in New England, notably Jack Kerouac. Thus Hirst, in a Gonzo act in itself, comes upon the French word “gonze”, roughly meaning “bloke”.

Linguistics and etymology can obviously only take us so far, even, as with social linguistics, we dispense with the fetishism of the utterance or worse, biological determinism. Hirst reverts to a politically detached axiology, defining Gonzo in pure stylistic terms, thus Michael Moore is his closest modern analogue to Gonzo. All things told, he takes a peripheral view when it comes to definition, but he does have a handle on the fact that the concept is irresistably transformative. Hirst’s error, in attempting to build from his etymological research, was to extricate “Gonzo” from how Thompson himself constructed the term, first using it to apply to his own project in what became Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. More significant is the figure of Dr. Gonzo in the aforementioned book, Thompson’s name for his road dog, Oscar Acosta.

Hunter S. Thompson and Oscar Z. Acosta at Caesar's Palace Bar, 26 April 1971, 03:00 am.

Acosta was a radical Leftist and Chicano militant, an activist lawyer, close to the Brown Berets and the broader west coast Latinx left. The whole purpose of Thompson and Acosta’s actual road trip to Vegas was for an article Thompson was writing on Acosta, for Acosta to be able to feel safe and away from the melee of LA and what he perhaps rightly perceived as constant political monitoring. Thus, the irony of Thompson and Acosta arriving in Las Vegas and seeing a convention of the drug enforcement agency drove Acosta to a dark mania, as the two of them partied with LSD, booze and cocaine. What seems fictional in the book is all too real. A man who was legitimately being persecuted found himself surrounded by persecutors. Acosta disappeared in Mexico in 1974, never to be found. Thompson thought it may have been drug dealers – as the overlap between the left underground and the drug trade was porous at the time, or it could have been political assassination, or a bit of both.

Gonzo, thus, is deliberately applied by Thompson to a figure who was in practical terms a revolutionary. And he sees, in his metaphor of the great wave, the revolution as being on the cusp of defeat, of the rise and solidification of Nixonian reaction and the failure of a real encounter between the New Left and the sixties counterculture, all of those, who in different ways, had not a few years earlier, seen revolution or some form of transformation as inevitable. Those like Acosta, who swam against the tide, were Gonzo. Gonzo was to retain that aura of the long sixties beyond it, to tempt fate and also to revel in absurdity, to demystify in practice as well as in the written word. To keep socialism weird, queer, and evocative of fear is to move towards a Gonzo Marxism.

Jordy Cummings is an editor of Red Wedge.