There are two main overlapping arenas for contemporary art: the established art market and the academic avant-garde. The artist’s relationship to these is defined by petit-bourgeois commodity production and academic research. The middle-class commodity production of the market is shaped at one end by highly successful so-called “art entrepreneurs” (a tiny fraction of the total) and at the other end by a mass of “dark matter”: tens of thousands of working-artists who cannot even dream of making a living at their craft; but whose production is central to the maintenance of the art world. They are usually working-class in their “day jobs” and often impoverished. The academic avant-garde is characterized, economically and socially, by a (often proletarian) relationship to austerity in higher education, a highly rarefied and individualized relationship to academic rites (tenure, publishing, influence), and the inheritance of the avant-garde mantle.

In any case the artist is always on the make; trying to become in materiality what they already are in essence (“artist”). The artist is therefore trapped between the rigidity of their social position and the supposed fluidity and openness of the contemporary art object or gesture. Within that trap are the unspoken things that the work cannot be: too didactic, too earnest or too confrontational (despite the 1990s craze for institutional critique). Meanwhile, the academic avant-garde can scoff at the commodity status of the art object, jealously and rightly guarding its tenure (its own commodity status), while ignoring the fact that the untenured artist must sell their work in order to eat (or at least continue to spend hundreds of dollars on supplies). Contemporary art suffers an unbearable lightness of being and an unbearable weight of becoming.

This is the first in a series of articles aiming to outline possible strategies for contemporary anti-capitalist studio art. It builds on previous essays, particularly “A Thousand Lost Worlds: Notes on Gothic Marxism” and “On a New History Painting.” This article appeared in modified form on the "Evicted Art Blog." While it takes its starting point from the work of Ilya Kabakov it aims to generalize.

Interrupting Disbelief

Following the collapse of the avant-garde model, all art became, in part, a desperate attempt to answer the question of what art should now be: art’s ontological being after post-modernism and after the collapse of so-called “socialism.” For (a romantic or humanist) Marxism the question is one of interrupting cynical disbelief through the re-establishment of distance and aura, but anchored to concerns beyond the rarefied art world — anchored in the proletarian reality and the fantastic hidden within the mundane and banal. Such an approach cannot hope to spur the spectator into action (in the way of Brechtian theater) but neither can it remain an intellectual game. Instead, it aims to “buy time” until the imagination of revolutionary actuality returns.

It might seem odd that Ilya Kabakov could be a paradigmatic figure for such a project. His work is bound up with the supposed failures of utopian modernism, but Kabakov’s reproduction of social and artistic tensions within his work (totality/subjectivity, the mundane/the cosmic, the narrative/the conceptual, the proletarian individual/the collective utopia, modernity/post-modernity) provide clues for potential strategies to grapple with art’s weakening totality.

Moscow Conceptualism

Ilya Kabakov is the Soviet born artist best known internationally for his installation art — work that deals with the dual social-spiritual aspects of art as they intersect with the history of the USSR and social life more generally. Kabakov is also interesting in that he has tried to develop a theoretical approach to installation work. He calls this “total installation” — based on the German idea of Gesamtkunstwurk — the idea of “total art” initially associated with Richard Wagner. He did this after spending most of his life working officially as a children’s book illustrator and “unofficially” as a part of the underground Moscow conceptual art scene.[1]

Ilya Kabakov

As Lara Weibgen argues, the Soviet Union was a “constant presence” in modern art. The early 20th century Russian and Soviet avant-garde played a major role in the narratives of modernism. Malevich arrived at the “zero” of painting several decades before Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings or John Cage’s 4’33. There were the “utopian” dreams of Constructivism. Moreover, the existence of the USSR, however disfigured by its reality, reinforced ideological polarization between capitalists (liberal and conservative) and Marxists (democratic and Stalinist). Prior to the collapse of the USSR (and the ascendancy of post-modernism), intellectual debates were pushed into two largely hostile camps.[2]

Of course, these debates were largely held outside of the Soviet block. Conceptual art in the West could be read, in large part, as a rejection of the commodification of art in a “free market.”[3] The dematerialization of the art object was bound up with the rebellions of the late 1960s (the French general strike, the student and Black power rebellions of the U.S., the spread of Maoist ideas).[4] Battle lines were drawn, in (distorted) Marxist terms against the liberal (or social-democratic) corporatist state, consumer culture, and the attendant problems of imperialism, racism, sexism, etc. By the time of the 1970s economic crisis and the return of classical Marxist pre-occupations the radical gestures of western dematerialization were already being metabolized by the “art world.”

Conceptual art in Moscow came into being in a different and totalitarian context. It drew on Russian and Soviet literary traditions. It therefore developed a far stronger narrative aspect, within and against the dominant narratives of Soviet life.[5] If conceptualism in the West was driven toward categorization and definition, Moscow conceptualism was driven by a sort of “graphomania” (a compulsion to write).[6] The targets of Moscow conceptualism were not the market or the commodification of culture, rather, as Boris Groys argues, the “rules of the symbolic economy that governed the Soviet Union in general.”[7] This narrative conceptualism was connected to the way “normal” life functioned in the USSR. As Ilya Kabakov recalls, “[l]ife consisted of two layers, each person was a schizophrenic. Any person — a factory worker, intellectual, artist — had a split personality.”[8]

[After Stalin] this dual life became firmly established, it was recognized by absolutely everyone, including the official organs of the secret police. There was a very strict distinction between public and domestic, kitchen life.[9]

As each individual moved through the “total installation” of the USSR (as Boris Groys describes it) he or she enacted a performance. Christopher Marinos argues that this fed the divergence between an “Anglo-Saxon” conceptualism rooted in “Apollonian” opposition to “the market and the institutions” and a “Dionysian” Soviet conceptualism.[10] Conceptual art in Moscow was underground, sometimes censored, sometimes tolerated. Its audience was largely an informal network of a few dozen artists, intellectuals, poets and musicians (including Kabakov and Groys).[11] The work was seen informally in apartments and studios. As Lara Weibgen puts it, such work did not aim to critique the art institutions in which it lived, rather it sought to “’compensate for the absent museums of contemporary art’ through various practices of self-institutionalization.”[12] It was, in many ways, a closed world of dreaming. The small underground art market did not significantly shape the practice of unofficial artists. The preoccupation was with the lofty (professed) ideals of the state and the stark reality of everyday life. A sort of earnest irony was born, in which “speaking in quotations” was the only way left to be sincere.[13] Groys described the products of this earnest irony as “Romantic Conceptualism” and later as a “discursive pop art.”[14]

Ten Characters

It was in this context Kabakov began his Ten Characters series (1969-1975). That series would become the basis of his better-known installation work. Each book is a collection about ten “little heroes,” depicted in ink and colored pencil, living in the “margins” of Soviet life as visionary (but utterly unknown) artists.[15]

“Sitting-in-the-closet Primakov” or “Agonizing Surikov”… alongside captions of commentary from acquaintances of said “artist.” Thus, the interrogation of the very notion of “authorship” and a preoccupation with the possibility of creating the context, and controlling the reception of artistic products may be described as longstanding features of Kabakov’s practice.[16]

These subjects, however, are not treated as simply heroic or as merely banal. Instead they are presented with a kind of proletarian magical realism. Kabakov argues that he follows the tradition of Gogol, Dostoevsky and Chekhov: “not the heroic Soviet person, not the Western superman,” but, instead, a profound longing for escape and utopia among atomized individuals.[17] The mundane is always there, as Joyce Beckenstein argues, the central image is the fly, emblematic of the “dirty,” of “garbage” both “energetic and sad.”[18] But the mundane is also connected to a fantastic psychological and/or cosmic ascension (or plan for ascension). Ten Characters “tell 10 fables,” Beckenstein writes, “suggest 10 positions from which homo sovieticus can react to the world. 10 psychological attitudes. 10 perspectives on emptiness and white. 10 parodies of the aesthetic traditions through which Kabakov evolved.”[19] It is, of course, somewhat more complicated. Drawing on the history of Malevich and other Soviet modernists, Kabakov is well aware that white can also be used to symbolize the cosmic. He has a push-pull relationship with (the now lost) official Soviet culture. He argues:

The new world was supposed to carry the perception of the cosmic. A new cosmos. All ideas come from the cosmos, and not from social life. The Russian avant-garde believed that a new cosmic era had begun. Technology, steamships, airplanes, steam engines, were all perceived to be the signs of the cosmos….

All the Russian avant-gardists were accomplished visionaries, mystics, from Filonov to Malevich.[20]

In The Flying Komarov (1972-1975), a part of the Ten Characters series, a man leaps into space, after a fight with his wife, joining “kindred souls” sailing through an infinite space.[21]

Incomplete Notes on Russian and Soviet Literature

In as much as Kabakov stands in the tradition of Chekhov or Gogol, he stands with and against the state mythologies and the particular modes of storytelling that dominated in the USSR.[22] After an initial wave of literary innovation in the early Soviet Union (see Heart of a Dog, Red Calvary and We), the prohibitive strictures of Socialist Realism emphasized the so-called production novel (exemplified by Fyodor Gladkov’s Cement). The production novel also turned the proletarian figure into a hero. It did so, however, through the sacrifice of the hero’s subjectivity for the state and economic output. Such novels have long been judged primarily by their literary failures, but as Wendy Koenig argues, when they are studied as examples of storytelling they present a more complex reality.[23]

This echoes Boris Groys’ Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin — translated as The Total Art of Stalinism — and the notion that the entire USSR was, in fact, a massive installation project.[24] Groys’ argument that Socialist Realism was primarily a product of the avant-garde itself (suprematism, constructivism, etc.) is, of course, philosophically idealist (and incorrect). The basis of the shift between the open avant-garde at the time of the October Revolution and the closed world of Socialist Realism (in the later 1920s) was the degeneration of the Russian Revolution. As working-class rule ebbed (in 1918 and 1919) it was replaced with the rule of bureaucrats, who were becoming increasingly conscious of their own interests. The logic of solidarity and openness that characterized the early revolution was replaced by an ideology that merely dressed in its language. The emphasis on “classical models” — most famously articulated by Lukacs in his debates with Brecht — was emblematic of the revolution’s decline.

Regardless, the cultural parallels between the total fabrication of Soviet life and the cosmological gesamtkunstwerk of Lissitsky (and others), is telling. The dream of “reunification of the arts” raises the prospect that “every artist is a dictator.”[25] It is also why the only consistent Marxist attitude toward artistic production is anarchist.

Total Installation and the Cave

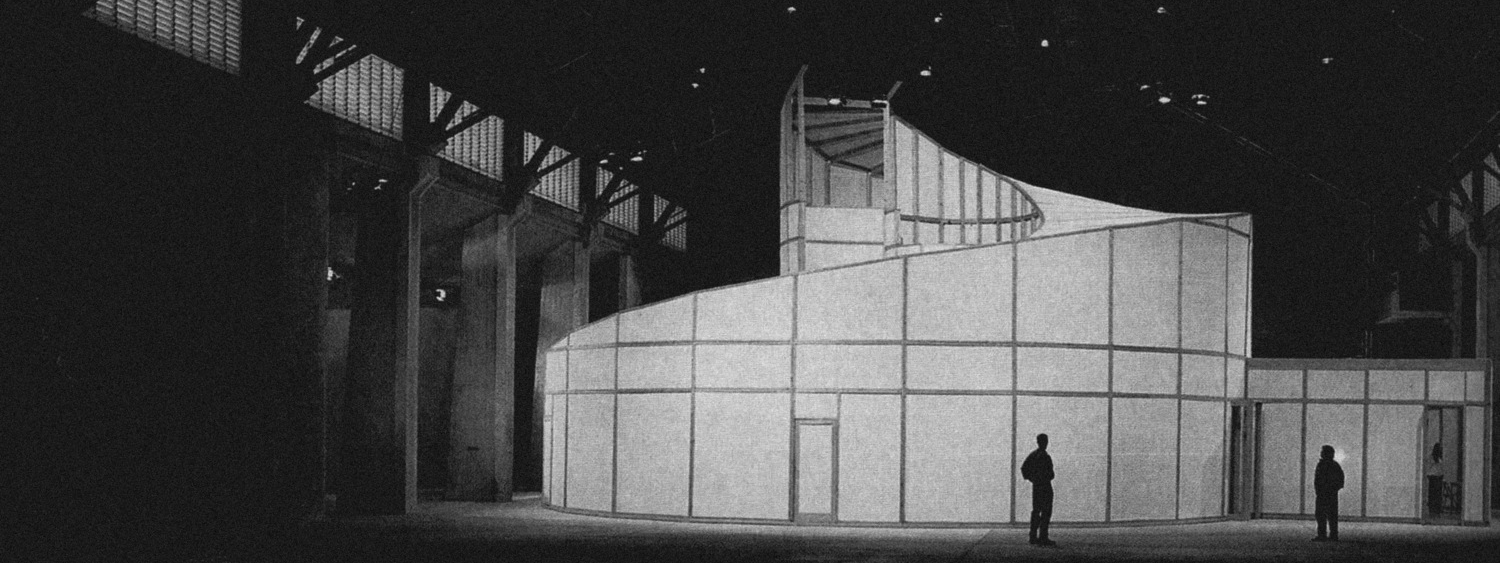

As Kabakov began to make installations outside the USSR in the late 1980s it was noted that his work contrasted with western installation, most of all, in using the entirety of a space.[26] Kabakov argues:

Installation is a three-dimensional invention, and one of its features is a claim to totality, to a connection with universals, to certain models that, in the general view, no longer exist. Such claims take us back to the epic genre, to literature, to something immobile and yet worrisome… An attempt is being made to encompass all the levels of the world.”[27]

Kabakov, despite (more than justified) antipathy toward Soviet cultural life, aims to “combat” the “loss of a single unifying voice.” By inventing fictional characters the possibility of such a voice (of god, revolution, cosmological ascension, of modernity) returns — albeit only within the space assigned to the character.[28] The viewer is allowed to, as when reading a novel, suspend disbelief. As Margarita Tupitsyn notes, the “installation space is also a surrogate cave” — as in the possible origin of art (in cave painting) and in a Platonic sense.[29] The installation serves as a return to the primordial origins of art. It also confirms Plato’s nightmares about artists in its embrace of shadow and facsimile as emotional or philosophical “truth” (“truth” that cannot be achieved by looking at the actual figures that cast the shadow). Kabakov knows, as Joseph Beuys learned, that “claims of mystical powers and otherworldly intervention have become a mark of bad taste… like farting at a table.”[30] By creating a narrative fiction, visually and in space, Kabakov can allow, for a moment, the mystical (and other) dreams to become “real;” to “reunite art with ritual.”[31] Because the story is not presented as fact (as with Beuys) it becomes permissible.

Installation and Painting

The use of painting continues this intercourse of fiction and nonfiction, belief and disbelief.

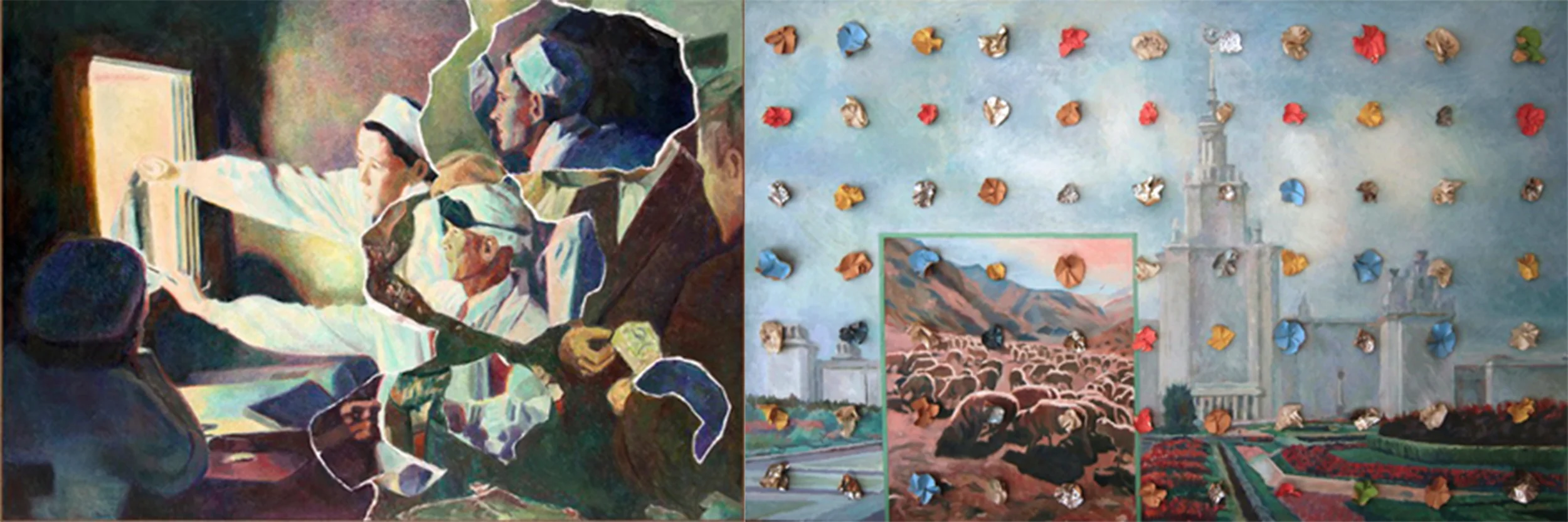

Kabakov has repeatedly used paintings within his installations, starting with his Russia series in 1969, in which large paintings were produced using the official red paint of the Russian flag and the official drab green paint used on Russian government buildings. The color produced was a sickening brown. Later paintings-within-installation, however, were not the product of such clear conceptual gestures. Kabakov is particularly interested in Cezannism, the “officially forbidden” painting style rooted in late 19th and early 20th century Russian modernism, which was “based on a particular interpretation of Cezanne’s work that focused upon balance and painterliness.”[32] Several of the paintings by Kabakov’s fictional artists employ this style within his installations, evoking a particular moment of avant-garde totality and later unofficial art practices, and a particular transparent gesture of the early unofficial Soviet artists.

“Modernists used paintings,” Margarita Tupitsyn argues, “as a point of departure” and did so in the context of a profound interest in theater, as they aimed to create a “total; artistic universe.”[33] Such faith in the heroic painting (and painter) is no longer possible. The (modernist) painting (and painter) has suffered the same fate as the authoritative voice. “The relationship of painting to the space beyond the painting,” Kabakov argues, “is the relationship of the sacral and secular space.”[34] The incorporation of painting into the total installation, therefore, creates a multiple interaction of profane and sacred worlds: real world, sacred art space, secular installation, sacred painting.[35] This is a reworking, within total installation, of the dynamic between belief and disbelief. This is done with the creation of multiple distances, including distancing the artist from the role of painter. The product is a (temporary) return to “auratricity.”[36] It is why Kabakov believes installation involves a kind of “magical spell.”[37] Just as the narrative allows for the re-introduction of the mystical, the space around the painting allows for the re-introduction of the modernist gesture.

Kabakov’s work does not so much ratify the death of the author, but create strategies to reclaim authorship, despite his protestations. Kabakov argues, within the installation, his paintings “belong to no one,” but they operate much like versions of his Ten Characters, fictions that quite clearly belong to Kabakov — including his biography and experiences.[38] This is not a problem, even if Kabakov believes it to be. The paintings act, in the context of the installation, to invert the Brechtian maxim: interrupting disbelief. Here the nature of painting reinforces the narrative context in an anti-post-modern pose.[39] His distancing techniques are not “detached” but “characterized by melancholy and longing.”[40] They allow the viewer to re-engage with a modernist gesture as well as pre-modern ideas of the spiritual in art. This is a Romantic modernism not unlike that of Malevich or Breton.

Kabakov believes, rightly, there are things beyond understanding and categorization. “When we say everything is speech,” he argues, “we are constantly immersed in river of speech, and therefore we basically cannot say anything… There must be certain nodules that speech never penetrates, and about which we literally have nothing to say.”[41] This silence and deference to dreams[42] is a welcome counter to both the humorless obsessions of would be visual theorists and the superficial complicities of the art world.

It is this dynamic within Kabakov’s work that helps provide a basis for a humanist Marxist approach to contemporary cultural production.

Weak Gestures and Total Installation

In Western art I was astounded by the unbelievable individualistic isolation, loneliness and exclusivity, from Pollock to whomever… I saw this as a deformation of Western ideology, because the image of the little man comes from the tradition of the Enlightenment. The intellectual in this sense is understood not as a class attribute, but as a certain kind of norm of the individual. He cares, sacrifices and is compassionate.[43]

The social, cultural and historic context that shaped Ilya Kabakov’s work and worldview is particular to the Stalinist USSR. One cannot hope to transport it as a model to the contemporary (or historic) United States. At the same time there are a number of problems facing contemporary art that a mining of Kabakov’s method would illuminate, in particular what it means to counter a constantly changing digital gesamtkunstwerk. This total installation is not totalitarian (in any classical sense) but is characterized by a political system in which only secondary matters are allowed significant discussion. The citizens of late neoliberalism are allowed to say anything they like (generally speaking) but it simply does not matter (on the macro level it does not matter, on the micro level one can still lose one’s job, be beaten by the police, etc.). Indeed, the system depends on all speech and all imagery becoming white noise. Whereas the Soviet citizen learned to speak two distinct languages, we speak dozens of languages, striking poses, searching for a presence that no longer exists. The dominant utopian narratives particular to North America no longer correspond to everyday life, an everyday life that reproduces images of itself at all times. Kabakov’s proletarian “artists” sought escape. Our “artists” seek rescue. Utopia, for Kabakov, is a literary device.[44] North Americans believe utopia is an actual place. Our narratives told us we lived in it. As our utopia decays and falls apart we are at a loss.

Boris Groys and Jacques Ranciere have identified the contours of this problem within contemporary art, although their solutions, coming from different ideological perspectives, are incomplete. Joseph Beuys’ slogan, “everyone is an artist,” (and similar notions of the avant-garde) carried a utopian promise, tied either to an abstract romanticism and/or actually existing political alternatives. Art was deprofessionalized but art remains a rarefied profession. In theory everyone (and everything) can be an artist (or art), but the actual structures of the world prevent this. The “dominant mode of contemporary art production,” according to Groys, is an “academicized late avant-garde.”[45] So, in lieu of the messianic avant-garde we have a “weak messianism” and a “weak universalism.” In the absence of a material world in which everyone is genuinely an artist, Kabakov substitutes a fictional world in which utopian dreams can be realized (or at least schemed). This draws attention to modernity’s failures while simultaneously creating space for the empathy and totalizing that were the hallmark of modernity at its best.

Perry Anderson famously argued that the “imaginative proximity of social revolution” was one of the three decisive coordinates of modernism; however, if we look at the peripheral modernism of Tango and Tarab, Kroncong and Marabi, the imaginative proximity of revolution must be understood to include not simply the remarkable European uprisings that produced “soviets” and “councils” in the cities of eastern and central Europe but the world-wide wave of anti-colonial rebellions that stretched from the May Fourth Movement in China in 1919 and the non-cooperation movement Gandhi launched in the wake of the 1919 Amritsar massacre to the 1919 Wafd rebellion in Egypt as well as the general strikes across port cities, mining towns and plantations: the Semana Trágica of January 1919 in Buenos Aires, the 1920 strike of Japanese sugar plantation workers on Hawaii's Oahu, the 1922 Rand rebellion on South Africa's Witswatersrand, and the 1925 killing of protesters in Shanghai that provoked the May 30 movement in Shanghai.[46]

Jacques Ranciere outlines, in “The Emancipated Spectator” and elsewhere, a fundamental truth of political art—that its ability to imagine “changing the world” was tied to directly to the actuality of social movements and revolutions in the 20th century.[47] The collapse of social movements and alternatives meant that political art found itself in a position that could be called “weak didacticism.” The impulse of Epic Theater, Ranciere argues, was to push the spectator away from a passive role (looking) and into action.[48] Of course, in the 1920s and 1930s audiences were already “primed” for action by the crises of the interwar period: revolutions, the rise of fascism, etc. Regardless, Ranciere asks, why is acting given primacy over looking?[49] There is a fatal flaw in the argument that art’s primary function is to spur the proletarian into action. Art does not work that way. There can be “great” didactic art, but this art is a minor light in the firmament of social revolution. Art serves other basic human needs (which overlap but are not identical to the needs served by social struggle).

What is of most interest, in relationship to Kabakov’s “Total Installation” and narrative conceptualism, is Ranciere’s analysis of mediation and distance. “The primary knowledge,” he argues, “that the master owns is the ‘knowledge of ignorance.’” The instructor calibrates his vastly superior knowledge, at all times, a few steps ahead of those he instructs. There is always a delay inherent in the transmission of knowledge.[50] It is within that delay that the instructor takes on a mythological and auric quality. Ranciere argues that there has been a kind-of equalization of the way in which knowledge is transferred, an “emancipation” that “starts from the principle of equality.”

It begins when we dismiss the opposition between looking and acting and understand that the distribution of the visible itself is part of the configuration of domination and subjection.[51]

Ranciere is only half-right. In an unequal, oppressive, class society—in which spectacle plays a significant but not determinant role—looking is not necessarily a privileged position. The spectator only appears to have been emancipated. One is reminded of Anatole France’s remark that the law, in its equality, forbids both the rich and the poor from sleeping under the bridges of Paris. The digital dystopia promises the emancipation of seeing for rich and poor, worker and capitalist, black and white, male and female, queer and straight, but that is not how the social interactions surrounding (and shaping) the images proceed. Just as the narrative of Soviet life was one of equality, so was the narrative of the incipient digital age. But whereas looking flatters the powerful, it tends to categorize and empty the weak. Ranciere is right when he argues that “words are just words.”[52] But that has not always been the case. At one time words moved people to storm palaces. At one time they were considered “magic” things that held power over the natural world. The day will come when words regain such power.

Of course the particularities of Kabakov’s method, his unique cultural and individual origin, cannot be reproduced. An American “Total Installation” would, of necessity, emphasize different cultural points and have a different relationship to the iconographic and indexical. Nevertheless, Kabakov’s method mitigates the weakness of avant-garde gestures, providing tools for artists to propose alternative pasts and futures, buying time for the return of “the proximity of social revolution,” the imagination it brings with it, and the reclamation of both heaven and earth. It is an art that serves as guardian of the “word” and all that is beyond words.

Footnotes

- Amy Ingrid Schlegal, “The Kabakov Phenomenon,” Art Journal Vol. 58 No. 4 (Winter, 1999), 99

- Lara Weibgen, “Moscow Conceptualism, or the Visual Logic of Late Socialism,” Art Journal (Fall 2011), 109

- Michael Corris, “Total Engagement: Moscow Conceptual Art: Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt,” Art Monthly Issue 319 (September, 2008), 18-20

- See Lucy Lippard, Six Years of Dematerialization

- Corris, 18-20

- Schlegal, 99

- Corris, 18-20

- Anton Vidokle, “In Conversation with Ilya and Emilia Kabakov,” e-flux journal #40 (December, 2012)

- Vidokle

- Christopher Marinos, “Total Enlightenment: Conceptual Art in Moscow 1960-1990: Schirn Kunsthalle,” Modern Painters Vol. 20 Issue 9 (October, 2008), 94

- Vidokle

- Weibgen, 109

- Weibgen, 122 and Schlegal, 99

- Marinos, 94

- Wendy Koenig, “The Heroic Generation: Fictional Socialist Realist Painters in the Work of Ilya Kabokov,” Southeastern College Art Conference Review Vol. 10 Issue 4, 448-455

- Koenig, 448-455

- Vidokle

- Joyce Beckenstein, “Absurdities as Absurd as Reality,” Sculpture 38 (July/August 2014. 38)

- Beckenstein, 34

- Vidokle

- Beckenstein, 34

- Koenig, 448-455

- Koenig, 448-455

- Koenig, and Weibgen, 110

- Koenig, 448-455

- Beckenstein, 35

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, “About Installation,” Art Journal Vol. 58 No. 4 (Winter, 1999), 63

- David Jeffreys, “Yoko Ono, Gustav Metzger and Ilya Kabakov: review,” The Burlington Magazine Vol. 141 No. 1153 (April, 1999), 243.

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 64

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 64

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 66

- Koenig, 448-455

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 66

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 66

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 67

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 65 and Koenig, 448-455

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 71

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 67-68

- Koenig, 448-455

- Koenig, 448-455

- Ilya Kabakov, Margarita Tupitsyn and Victor Tupitsyn, 73

- Beckenstein, 37

- Vidokle

- Beckenstein, 39

- Boris Groys, “The Weak Universalism,” e-flux journal #5 (April 2010).

- Michael Denning, Noise Uprising: The Audiopolitics of a World Musical Revolution (forthcoming)

- Ben Davis, “Ranciere, For Dummies," ArtNet, 2006)

- Jacques Ranciere, “The Emancipated Spectator,” Artforum (March 2007), 271-275

- Ranciere, 271-275

- Ranciere, 278

- Ranciere, 278

- Ranciere, 280

Adam Turl is an artist, writer and socialist currently living in St. Louis, Missouri, and is an editor at Red Wedge. He writes the Evicted Art Blog at Red Wedge.